Alemtuzumab is a monoclonal antibody that has been used to treat refractory cases of Sézary syndrome (SS) and advanced mycosis fungoides.

We present 5 patients with SS who were treated with alemtuzumab between 2008 and 2012, with an overall response rate of 80% (40% partial response and 40% complete response). A regimen of 10mg administered subcutaneously was well tolerated with acceptable toxicity. The median duration of response was 13 months. However, one patient remains in complete remission after 67 months, a remarkable outcome given the low survival rate associated with SS.

In conclusion, we believe that alemtuzumab may be useful in cases of SS refractory to other treatments. As there are no curative treatments for SS, alemtuzumab should be considered as a therapeutic option.

El alemtuzumab es un anticuerpo monoclonal que se ha utilizado como terapéutica en casos refractarios de síndrome de Sézary (SS) y micosis fungoide en estadio avanzado.

Presentamos 5 pacientes diagnosticados de SS tratados con alemtuzumab entre los años 2008 y 2012, con una tasa de respuesta global del 80% (40% respuestas parciales y 40% respuestas completas). La pauta de 10mg vía subcutánea fue bien tolerada y con una toxicidad aceptable. En nuestra casuística la mediana de duración de la respuesta fue de 13 meses, sin embargo uno de los pacientes continúa en remisión completa tras 67 meses, hecho destacable dada la baja supervivencia del SS.

Como conclusión, creemos que el alemtuzumab es un fármaco que podría ser útil en casos de SS refractarios a otros tratamientos. Dado que no existen tratamientos curativos en el SS, sería una alternativa terapéutica a tener en cuenta.

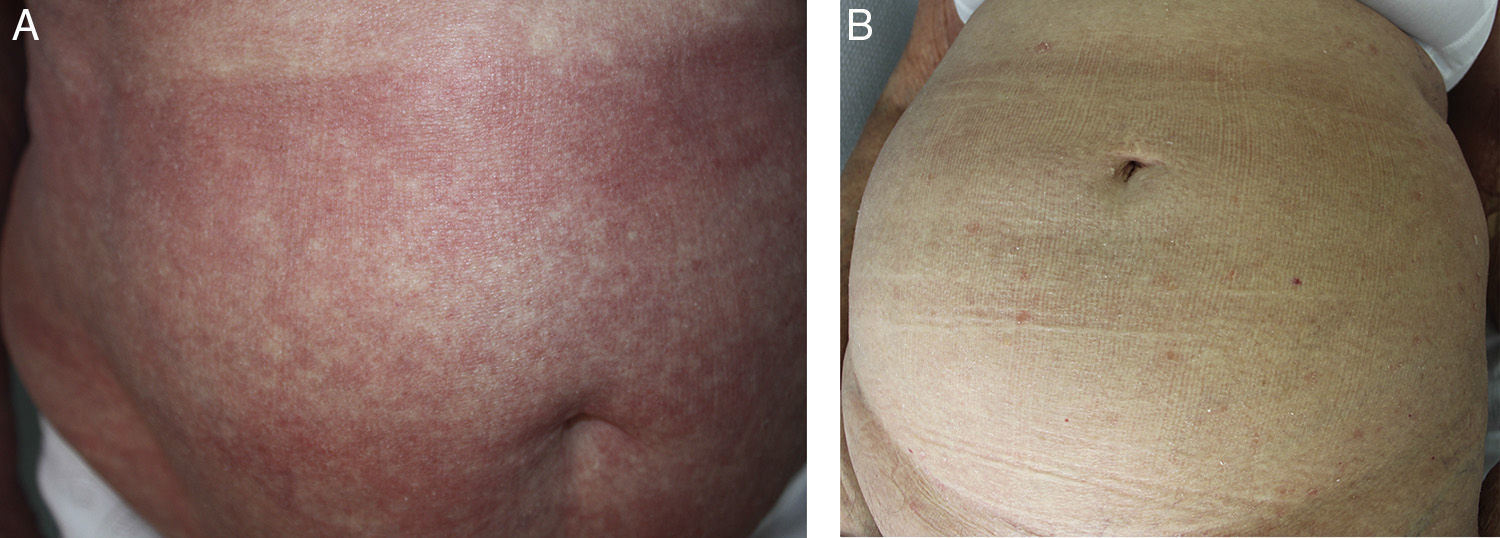

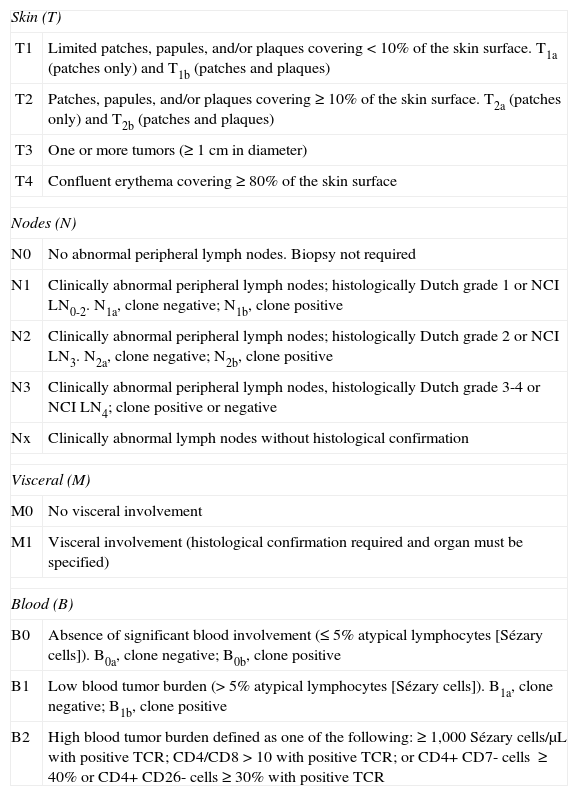

Sézary syndrome (SS) is a rare disorder that accounts for approximately 3% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. It is considered to be an aggressive variant characterized by the presence of erythroderma and circulating atypical T cells (Sézary cells), with or without lymphadenopathy.1 SS is classified as T4, N0-3, M0-1, B2 according to the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (Table 1).1–3 Pruritus is the main symptom and can have a marked impact on quality of life.

Classification of Mycosis Fungoides/Sézary Syndrome Proposed by the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

| Skin (T) | |

| T1 | Limited patches, papules, and/or plaques covering <10% of the skin surface. T1a (patches only) and T1b (patches and plaques) |

| T2 | Patches, papules, and/or plaques covering ≥10% of the skin surface. T2a (patches only) and T2b (patches and plaques) |

| T3 | One or more tumors (≥1cm in diameter) |

| T4 | Confluent erythema covering≥80% of the skin surface |

| Nodes (N) | |

| N0 | No abnormal peripheral lymph nodes. Biopsy not required |

| N1 | Clinically abnormal peripheral lymph nodes; histologically Dutch grade 1 or NCI LN0-2. N1a, clone negative; N1b, clone positive |

| N2 | Clinically abnormal peripheral lymph nodes; histologically Dutch grade 2 or NCI LN3. N2a, clone negative; N2b, clone positive |

| N3 | Clinically abnormal peripheral lymph nodes, histologically Dutch grade 3-4 or NCI LN4; clone positive or negative |

| Nx | Clinically abnormal lymph nodes without histological confirmation |

| Visceral (M) | |

| M0 | No visceral involvement |

| M1 | Visceral involvement (histological confirmation required and organ must be specified) |

| Blood (B) | |

| B0 | Absence of significant blood involvement (≤5% atypical lymphocytes [Sézary cells]). B0a, clone negative; B0b, clone positive |

| B1 | Low blood tumor burden (>5% atypical lymphocytes [Sézary cells]). B1a, clone negative; B1b, clone positive |

| B2 | High blood tumor burden defined as one of the following: ≥1,000 Sézary cells/μL with positive TCR; CD4/CD8>10 with positive TCR; or CD4+ CD7- cells ≥40% or CD4+ CD26- cells ≥30% with positive TCR |

Abbreviations: LN, lymph node; NCI, National Cancer Institute; TCR, T-cell receptor.

Source: Olsen et al.2

The prognosis is poor, with a 5-year survival of 24%; few lasting responses or remissions have been reported after treatment.4

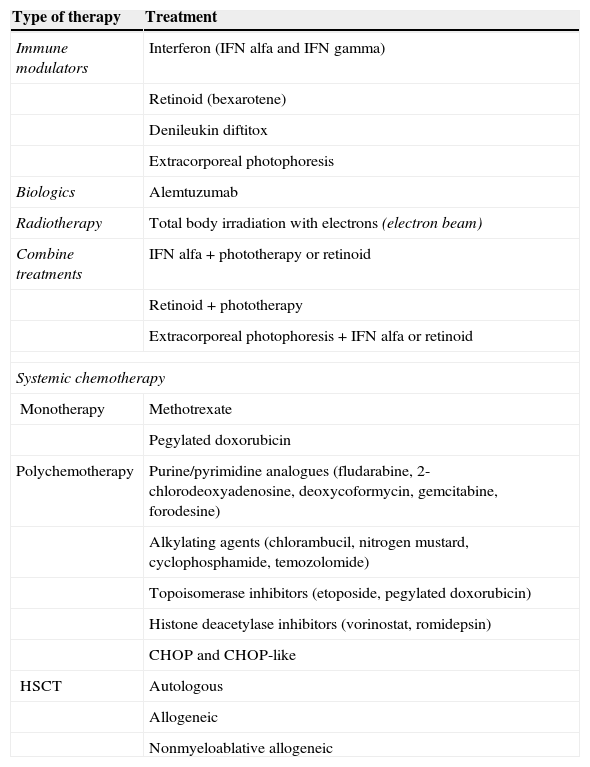

Systemic therapies are necessary for treatment, as those that exclusively target the skin are insufficient. The therapeutic choice is determined by the spread of the disease, the impact on quality of life, and the patient's age and comorbid conditions. Although several treatments are available for SS (Table 2),3 few efficacy studies have been published.

Treatments Used in Sézary Syndrome.

| Type of therapy | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Immune modulators | Interferon (IFN alfa and IFN gamma) |

| Retinoid (bexarotene) | |

| Denileukin diftitox | |

| Extracorporeal photophoresis | |

| Biologics | Alemtuzumab |

| Radiotherapy | Total body irradiation with electrons (electron beam) |

| Combine treatments | IFN alfa+phototherapy or retinoid |

| Retinoid+phototherapy | |

| Extracorporeal photophoresis+IFN alfa or retinoid | |

| Systemic chemotherapy | |

| Monotherapy | Methotrexate |

| Pegylated doxorubicin | |

| Polychemotherapy | Purine/pyrimidine analogues (fludarabine, 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine, deoxycoformycin, gemcitabine, forodesine) |

| Alkylating agents (chlorambucil, nitrogen mustard, cyclophosphamide, temozolomide) | |

| Topoisomerase inhibitors (etoposide, pegylated doxorubicin) | |

| Histone deacetylase inhibitors (vorinostat, romidepsin) | |

| CHOP and CHOP-like | |

| HSCT | Autologous |

| Allogeneic | |

| Nonmyeloablative allogeneic | |

Abbreviations: IFN, interferon; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Source: modified from Jawed et al.3

New therapies for SS, including biological therapies, have appeared in recent years. Alemtuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets the CD52 glycoprotein expressed on the surface of T and B cells, natural killer cells, monocytes, and macrophages, leading to a depletion of those cells in the peripheral blood.3,5 It is thought to act by direct cell lysis mediated by neutrophils, complement, and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity and apoptosis.3–6 In 2001, alemtuzumab was approved for the treatment of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, although some authors have used it in cases of refractory SS and advanced mycosis fungoides (MF).

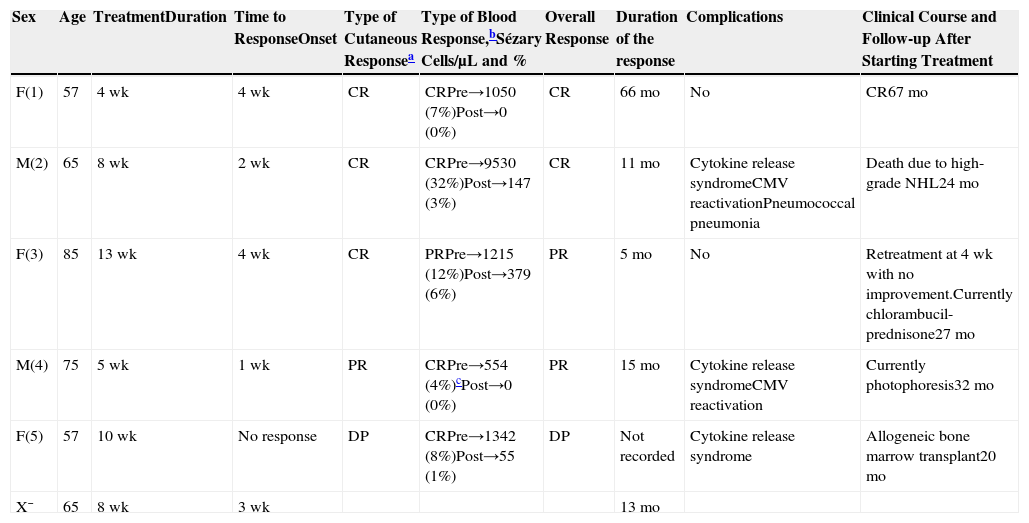

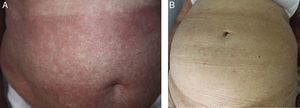

Case DescriptionsWe present 5 patients (3 women and 2 men) diagnosed with stage IVA1 SS (T4, N0, M0, B2) who were treated with alemtuzumab between 2008 and 2012. Four patients had undergone previous treatments (phototherapy, prednisone, methotrexate, gemcitabine, and bexarotene).

Data were gathered on the following variables to assess the treatment with alemtuzumab (Table 3): duration, type of response, time until onset of the response, duration of the response after the interruption of treatment, and peripheral blood Sézary cells. In addition, we analyzed the clinical course, follow-up period, and complications associated with alemtuzumab.

Our Series of 5 Patients With Sézary Syndrome Treated With Alemtuzumab.

| Sex | Age | TreatmentDuration | Time to ResponseOnset | Type of Cutaneous Responsea | Type of Blood Response,bSézary Cells/μL and % | Overall Response | Duration of the response | Complications | Clinical Course and Follow-up After Starting Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(1) | 57 | 4wk | 4wk | CR | CRPre→1050 (7%)Post→0 (0%) | CR | 66mo | No | CR67mo |

| M(2) | 65 | 8wk | 2wk | CR | CRPre→9530 (32%)Post→147 (3%) | CR | 11mo | Cytokine release syndromeCMV reactivationPneumococcal pneumonia | Death due to high-grade NHL24mo |

| F(3) | 85 | 13wk | 4wk | CR | PRPre→1215 (12%)Post→379 (6%) | PR | 5mo | No | Retreatment at 4wk with no improvement.Currently chlorambucil-prednisone27mo |

| M(4) | 75 | 5wk | 1wk | PR | CRPre→554 (4%)cPost→0 (0%) | PR | 15mo | Cytokine release syndromeCMV reactivation | Currently photophoresis32mo |

| F(5) | 57 | 10wk | No response | DP | CRPre→1342 (8%)Post→55 (1%) | DP | Not recorded | Cytokine release syndrome | Allogeneic bone marrow transplant20mo |

| X¯ | 65 | 8wk | 3wk | 13mo |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; DP, disease progression; F: female; M, male; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PR, partial response; X¯, median values.

CR: 100% lesion clearance; PR: 50%-99% clearance of initial lesions with no new tumors (T3) in patients with T1, T2, or T4; DP:≥25% increase in skin disease or new tumors (T3) in patients with T1, T2, or T4, or loss of response in patients with complete response or partial response.2

The type of response was classified as follows: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or disease progression (DP), in accordance with the study by Olsen et al.2 (Figure 1).

The regimen used was the subcutaneous administration of an initial dose of 3mg, followed by doses of 10mg 3 times per week.

The 5 patients received oral prophylaxis with sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, aciclovir, and fluconazole for Pneumocystis jiroveci, herpesvirus, and Candida. For cytomegalovirus (CMV) prophylaxis, we performed weekly measurement of the viral load and administered anticipatory treatment with oral valganciclovir in the event of reactivation.

A response was achieved in 4 of the 5 patients (overall response rate, 80%); there were 2 PR (40%) and 2 CR (40%). The median duration of treatment was 8 weeks (range, 4-13 weeks) and the median duration of the response after the interruption of treatment was 13 months (range, 5-66 months).

Complications included pneumococcal pneumonia in 1 patient, a cytokine release syndrome in 3, and subclinical CMV reactivation in 2. There were no hematological complications.

The median follow-up was 27 months (range, 23-67 months) after the initiation of treatment. One patient died at 24 months due to transformation to a high-grade nonHodgkin lymphoma. At the time of writing, 3 patients are in progression and one continues in complete remission 67 months after completing the treatment.

DiscussionAlemtuzumab has been used in both refractory, advanced-stage MF and in SS. The first description is from 1998 in 8 patients with MF.7 In 2003, the usefulness of alemtuzumab was demonstrated in a phase ii study of 22 patients with MF or SS.8 A number of small series and case reports have been published since that time. In the literature reviewed, we found a total of 13 series4,6–17 (detailed in Table 4) and 6 case reports of MF and SS.

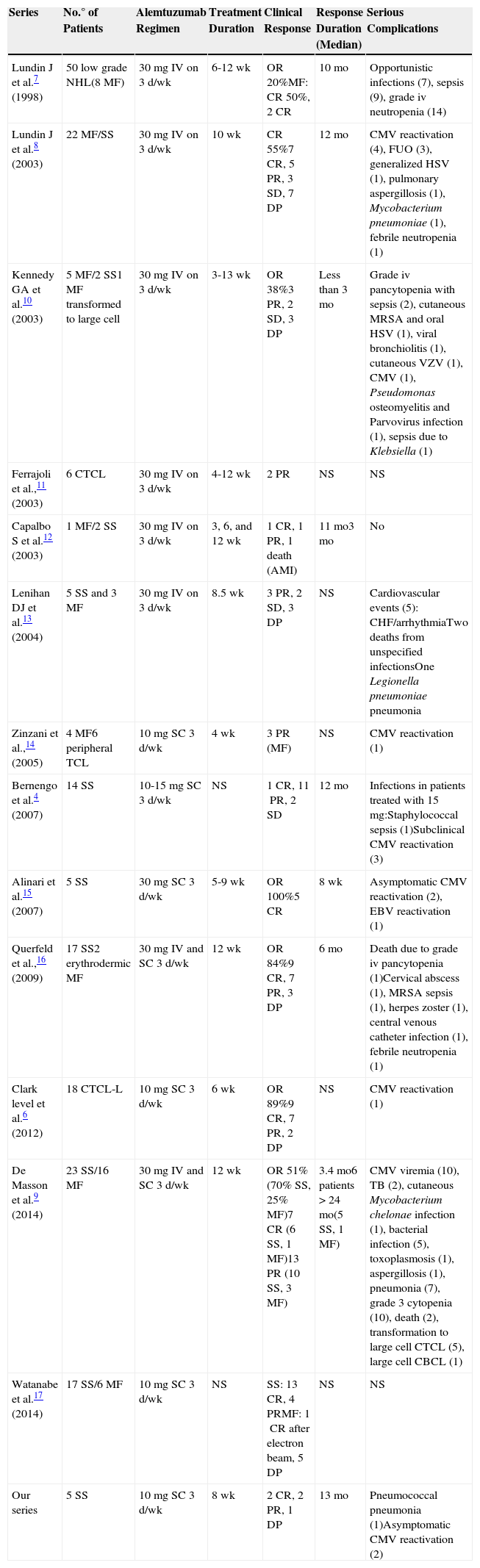

Published Series of Patients With SS/MF Treated With Alemtuzumab.

| Series | No.° of Patients | Alemtuzumab Regimen | Treatment Duration | Clinical Response | Response Duration (Median) | Serious Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lundin J et al.7 (1998) | 50 low grade NHL(8MF) | 30mg IV on 3d/wk | 6-12wk | OR20%MF: CR50%, 2CR | 10mo | Opportunistic infections (7), sepsis (9), grade iv neutropenia (14) |

| Lundin J et al.8 (2003) | 22MF/SS | 30mg IV on 3d/wk | 10wk | CR55%7CR, 5PR, 3SD, 7DP | 12mo | CMV reactivation (4), FUO (3), generalized HSV (1), pulmonary aspergillosis (1), Mycobacterium pneumoniae (1), febrile neutropenia (1) |

| Kennedy GA et al.10 (2003) | 5MF/2SS1MF transformed to large cell | 30mg IV on 3d/wk | 3-13wk | OR38%3PR, 2SD, 3DP | Less than 3mo | Grade iv pancytopenia with sepsis (2), cutaneous MRSA and oral HSV (1), viral bronchiolitis (1), cutaneous VZV (1), CMV (1), Pseudomonas osteomyelitis and Parvovirus infection (1), sepsis due to Klebsiella (1) |

| Ferrajoli et al.,11 (2003) | 6CTCL | 30mg IV on 3d/wk | 4-12wk | 2PR | NS | NS |

| Capalbo S et al.12 (2003) | 1MF/2SS | 30mg IV on 3d/wk | 3, 6, and 12wk | 1CR, 1PR, 1 death (AMI) | 11mo3mo | No |

| Lenihan DJ et al.13 (2004) | 5SS and 3MF | 30mg IV on 3d/wk | 8.5wk | 3PR, 2SD, 3DP | NS | Cardiovascular events (5): CHF/arrhythmiaTwo deaths from unspecified infectionsOne Legionella pneumoniae pneumonia |

| Zinzani et al.,14 (2005) | 4MF6peripheral TCL | 10mg SC 3d/wk | 4wk | 3PR (MF) | NS | CMV reactivation (1) |

| Bernengo et al.4 (2007) | 14SS | 10-15mg SC 3d/wk | NS | 1CR, 11PR, 2SD | 12mo | Infections in patients treated with 15mg:Staphylococcal sepsis (1)Subclinical CMV reactivation (3) |

| Alinari et al.15 (2007) | 5SS | 30mg SC 3d/wk | 5-9wk | OR100%5CR | 8wk | Asymptomatic CMV reactivation (2), EBV reactivation (1) |

| Querfeld et al.,16 (2009) | 17SS2erythrodermic MF | 30mg IV and SC 3d/wk | 12wk | OR84%9CR, 7PR, 3DP | 6mo | Death due to grade iv pancytopenia (1)Cervical abscess (1), MRSA sepsis (1), herpes zoster (1), central venous catheter infection (1), febrile neutropenia (1) |

| Clark level et al.6 (2012) | 18CTCL-L | 10mg SC 3d/wk | 6wk | OR89%9CR, 7PR, 2DP | NS | CMV reactivation (1) |

| De Masson et al.9 (2014) | 23SS/16MF | 30mg IV and SC 3d/wk | 12wk | OR51%(70% SS, 25% MF)7CR (6SS, 1MF)13PR (10SS, 3MF) | 3.4mo6 patients >24mo(5SS, 1MF) | CMV viremia (10), TB (2), cutaneous Mycobacterium chelonae infection (1), bacterial infection (5), toxoplasmosis (1), aspergillosis (1), pneumonia (7), grade 3 cytopenia (10), death (2), transformation to large cell CTCL (5), large cell CBCL (1) |

| Watanabe et al.17 (2014) | 17SS/6MF | 10mg SC 3d/wk | NS | SS: 13CR, 4PRMF: 1CR after electron beam, 5DP | NS | NS |

| Our series | 5SS | 10mg SC 3d/wk | 8wk | 2CR, 2PR, 1DP | 13mo | Pneumococcal pneumonia (1)Asymptomatic CMV reactivation (2) |

Abbreviations: AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CBCL, cutaneous B-cell lymphoma; CHF, congestive heart failure; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CR, complete response; CTCL, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; CTCL-L, leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; DP, disease progression; EBV, Epstein Barr virus; FUO, fever of unknown origin; HSV, herpes simplex virus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; OR, overall response; PR, partial response; SC, subcutaneous; SD, stable disease; TB, tuberculosis; TCL, T-cell lymphoma; VZV, varicella-zoster virus.

The overall responses to treatment in the 2 largest studies—of 22 and 39 patients—were 55% and 51%, respectively.8,9 The median duration of the response was 12 months, although this varied between series.4,6–17 In the series of 39 cases, lasting remissions (more than 2 years) were observed in 5 patients with SS but in only 1 patient with MF.9

The treatment regimen has changed over the years. The drug was administered intravenously in the initial studies: sequential initial doses of 3mg, 10mg, and 30mg were administered, followed by 30mg 3 times a week.7,8,10–13 It was subsequently observed that alemtuzumab could be equally effective administered subcutaneously at low doses.4,14

Treatment-related complications include infection and hematologic toxicity. The regimen of 10mg subcutaneously has been shown to be associated with a lower incidence of these side effects.4,14,15 The most common opportunistic infection is CMV reactivation, although other types of infection have also been reported.4 Myelosuppression is the most common hematologic toxicity.4

Cytokine release syndrome is the most common complication during treatment.7,8,10,11 Its frequency can be reduced by progressive dose escalation. Lenihan et al.13 published 4 cases of cardiac toxicity during the treatment of previously healthy patients. As this has not been observed in any other study, the possibility of a causal relationship remains under debate. A case of cutaneous hemophagocytosis at the site of injection of alemtuzumab was recently reported in a patient without Epstein-Barr virus reactivation.18

In the literature reviewed, alemtuzumab has been used indistinctly for MF and for SS, and advanced-stage SS and MF are grouped together in most studies. Erythrodermic MF is now considered to be progression of MF with absent or minimal blood involvement, in contrast to the situation with SS, which arises de novo and shows significant blood involvement.1 In 2012, Clark et al.6 reported that alemtuzumab may only be effective when blood involvement is present (in SS and in cases of erythrodermic MF with blood involvement). Those authors suggested that the 2 diseases arose from distinct types of memory T cells: the malignant lymphocytes in patients with SS have a CCR7+/L-selectin+ central memory cell phenotype (migratory cells that are found in peripheral blood, in the skin, and in lymph nodes), whereas the malignant lymphocytes of MF arise from nonmigratory cells resident in the skin and that are not found in the peripheral blood. Alemtuzumab depletes all T lymphocytes in the blood, but the population of cells resident in the skin will escape from the effect of the antibody and persist after treatment. In addition, alemtuzumab requires the presence of neutrophils and natural killer cells (both of which are present in blood but not in skin) to achieve lymphocyte depletion, and hence it only eliminates cells in the peripheral blood. The main candidates for this treatment are therefore patients with SS.

Unfortunately, authorization for the indication of this drug in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemic and other hematological diseases was withdrawn in August 2012, and it is currently only available for multiple sclerosis. For the treatment of patients with SS, alemtuzumab can only be obtained by individualized access via protocol.

ConclusionsWe have presented 5 cases of SS treated with alemtuzumab, achieving an 80% response rate. The regimen of 10mg administered subcutaneously was well tolerated and the median duration of the response was 13 months. Alemtuzumab can be a useful drug in cases of SS refractory to other treatments, achieving a rapid clinical response and improvement in quality of life, with a reduction or remission of the pruritus.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Please cite this article as: del Alcázar-Viladomiu E, Tuneu-Valls A, López-Pestaña A, Vidal-Manceñido MJ. Tratamiento del síndrome de Sézary con alemtuzumab: serie de 5 casos y revisión de la literatura. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:e33–e39.