Quality indicators are crucial for standardizing and guaranteeing the quality of health care practices. The Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) launched the CUDERMA Project to define quality indicators for the certification of specialized units in dermatology; the first 2 areas selected were psoriasis and dermato-oncology. The aim of this study was to achieve consensus on what should be evaluated by these indicators using a structured process comprising a literature review and selection of an initial list of indicators to be evaluated in a Delphi consensus study following review by a multidisciplinary group of experts. The selected indicators were evaluated by a panel of 28 dermatologists and classified as either “essential” or “of excellence”. The panel agreed on 84 indicators, which will be standardized and used to develop the certification standard for dermato-oncology units.

Los indicadores de calidad son una herramienta clave como garantía de calidad y homogenización de la asistencia sanitaria. En este contexto, la Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología ha diseñado el proyecto Certificación de unidades de dermatología (CUDERMA), una iniciativa que busca definir indicadores de calidad para certificar unidades de dermatología en distintos ámbitos, entre los que se seleccionaron psoriasis y dermato-oncología de forma inicial. Este estudio tuvo por objetivo consensuar los aspectos a evaluar por los indicadores, siguiendo un proceso estructurado para la revisión bibliográfica y elaboración de un set preliminar de indicadores, revisado por un grupo multidisciplinar de expertos, para su evaluación mediante un Consenso Delphi. Un panel de 28 dermatólogos evaluó los indicadores y los clasificó como «básicos» o «de excelencia», generando un conjunto de 84 indicadores consensuados que serán estandarizados para diseñar la norma para certificar las unidades de dermato-oncología.

Skin cancer incidence has risen significantly in recent decades.1,2 The latest estimates place global figures at 3.6 cases per 100000 inhabitants a year for cutaneous melanoma and 79.1 cases per 100000 inhabitants a year for nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC).3 The annual incidence in Spain ranges between 3.6 and 14 cases per 100000 inhabitants for melanoma1,4 and 79.7 and 88.7 cases per 100000 inhabitants for NMSC.1

Apart from its high incidence, skin cancer causes significant morbidity and mortality,2,3 particularly certain uncommon NMSCs, such as Merkel cell cancer, dermatofibrosarcoma, and cutaneous lymphoma. Related deaths and morbidity can result in significant years of potential life loss5,6 and notable economic losses linked not just to direct mortality costs but also to indirect morbidity costs associated with significant absenteeism.5 Skin cancer is the second leading cause of years lost to disability in the field of dermatology,7 with both melanoma and NMSC ranking among the top 25 causes of cancer-related disability-adjusted life years.3

Specialized dermato-oncology units have a key role in skin cancer management.8 Current practice in these units, however, varies across Spain,9 highlighting the need for measurable targets that define essential aspects of health care practice and delivery and can be used to improve the overall quality and performance of these units.

Quality indicators are used to define the extent to which a unit's facilities, resources, and performance meet a minimum set of quality standards. They are a particularly useful tool for evaluating the activity of specific departments and units and identifying areas for improvement; they can also be used to certify functional units.10,11

The CUDERMA (Certification of Dermatology Care Units) project is an initiative of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) designed to develop indicators for certifying functional dermatology units and ultimately improving quality in care. The project is divided into 3 phases: 1) identification of aspects that need to be evaluated via quality indicators; 2) harmonization and standardization of previously agreed-on aspects and establishment of names, definitions, standards, objective levels of compliance, and evidence of compliance; and 3) certification of units using the newly created standard. The aim of this study was to achieve consensus on aspects that should be covered by quality indicators for the certification of dermato-oncology units.

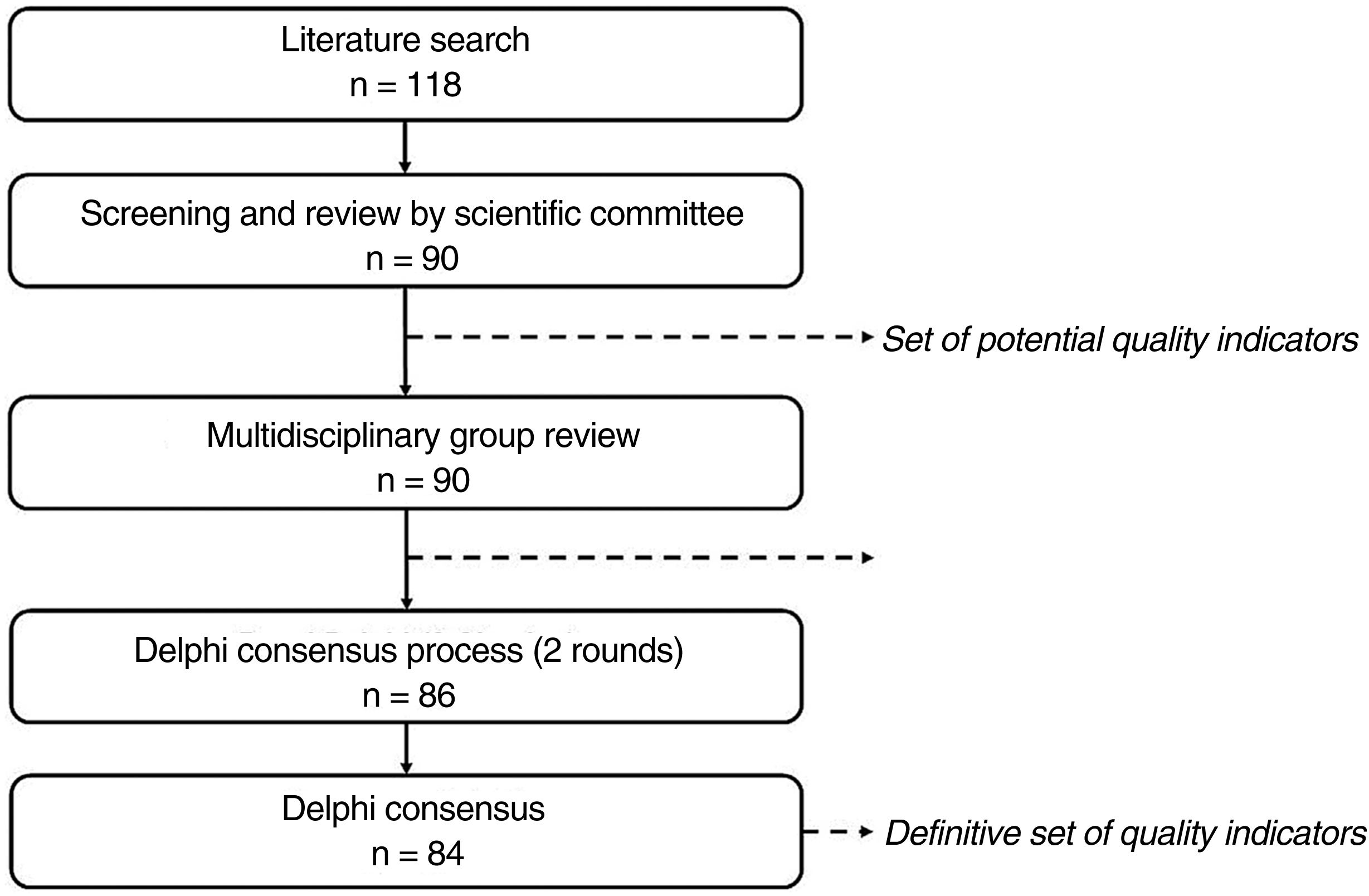

Material and MethodsWe designed a structured process using the Delphi consensus method to identify and screen potential quality indicators and subsequently achieve consensus on core aspects to assess during the certification of dermato-oncology units (Fig. 1).

The Delphi method seeks to achieve consensus among a group of participants on a Delphi panel via individual questionnaires. In successive rounds of the process, panelists are asked to rate potential items on a Likert-type scale and to add any pertinent comments. First-round responses are then used to design individualized questionnaires for the next round. These questionnaires are then analyzed to determine the level of consensus for each item evaluated.12–14

This study was divided into 3 stages: 1) identification of potential indicators, 2) review by a multidisciplinary group of experts, and 3) Delphi consensus process.

Working GroupThe CUDERMA project was led by a working group formed by 4 members of the overall coordinating group and a scientific committee comprising 7 dermatologists with experience in dermato-oncology (supplementary material, Table A.1). All 11 participants were members of the AEDV Spanish Dermato-Oncology and Surgery Group and received support from 3 methodology experts.

Phase 1: Identification of Potential Quality IndicatorsPotential quality indicators were identified by conducting a structured literature search following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (supplementary material, Table A.2).

The search targeted publications containing information on relevant aspects to evaluate during the certification of dermato-oncology units. This information was used to identify potential indicators. The working group was responsible for screening these indicators and proposing others.

The indicators were classified into 3 categories: structural indicators (to measure essential characteristics of dermato-oncology units), process indicators (to measure unit activities), and outcome indicators (to measure the results of these activities).10 The resulting list constituted the preliminary set of potential quality indicators.

Phase 2: Multidisciplinary Group ReviewThe potential indicators identified in the literature search were analyzed by a multidisciplinary group composed of 11 experts (supplementary material, Table A.1) specialized in nuclear medicine (n=2), medical oncology (n=2), radiation oncology (n=2), pathology (n=3), and diagnostic imaging (n=2).

The experts completed a questionnaire in which they rated the relevance of each indicator, and, where appropriate, added comments, suggested modifications, and proposed new indicators.

The working group analyzed the responses and drew up a preliminary list of indicators to use during the certification of dermato-oncology units.

Phase 3: Delphi Consensus ProcessThe preliminary list of indicators was analyzed by a Delphi panel formed by dermatologists specializing in dermato-oncology (supplementary material, TableA.1). The panelists participated in 2 Delphi consensus rounds before consensus was reached on which aspects should be evaluated during the dermato-oncology unit certification process.

In the first round, the panelists completed a questionnaire including the name and definition of each indicator. They were asked to score each indicator on a scale of 1–9, where 1 indicated not relevant and 9 extremely relevant. They also had to classify the indicators as either “essential” (crucial to the functioning of a dermato-oncology unit) or “of excellence” (aspects that added value to the functioning of the unit, achievement of health outcomes, and continuous improvement). In this round, each panelist could add comments or suggest changes for each indicator and propose new indicators.

The aim of the first round was to check whether the indicators conveyed the intended meaning and to identify possible new indicators for inclusion in the second round. For this second round, the working group designed individualized questionnaires for each panelist based on the first-round responses. The second set of questionnaires included the scores and classifications given to each indicator in the first round, the mean scores for the group as a whole, and the percentage of panelists who classified a given indicator as “essential”. No new proposals for indicators were accepted in this round.

The RAND/UCLA Delphi panel method, which applies statistical methods to provide a summary of consensus, was used to calculate the level of consensus on second-round ratings.15 Median scores for each item were categorized into 1 of 3 regions: 1–3, 4–6, or 7–9. Mean (SD) scores were also calculated to characterize questionnaire responses.

The first step was to calculate the level of agreement obtained for each indicator. Panelists were considered to agree on items scored within the median region by at least two-thirds of the panelists. In turn, they were considered to disagree when at least one-third of panelists scored the item within the 1–3 region and another third or more scored it within the 7–9 region. All other indications were rated as “indeterminate” (neither agreement nor disagreement).

For indicators with an agreed-on or indeterminate indication, it was determined whether the panelists were for or against their inclusion. Inclusion was considered “appropriate” when the median score was located in the region of 7–9 and “inappropriate” when it was located in the region of 1–3. Indications for items with a score in the range of 4–6 were considered “uncertain”.

The above methodology was adapted to identify “essential” indicators and indicators “of excellence”. Consensus was considered to have been achieved when more than two-thirds of the panelists assigned the same classification to a given indicator. In all other cases, the indications were classified as indeterminate. In a final meeting, the working group reviewed all indicators classified as uncertain, indeterminate, or with disagreement and decided whether to include or exclude them and whether they should be rated as essential or indicative of excellence.

ResultsIdentification of Potential Quality IndicatorsThe literature search yielded 121 publications (supplementary material, Fig. A.1), of which 94 were ruled out during initial screening. Detailed reading of the 27 remaining articles identified a potential list of 118 indicators.16–42

The working group examined these indicators and narrowed the list down to 90: 36 structural indicators, 52 process indicators, and 2 outcome indicators.

Phase 2: Multidisciplinary group reviewThe multidisciplinary group examined the potential indicators and where appropriate reformulated definitions and classifications. They also removed 11 indicators, leaving a total of 79 indicators (24 structural indicators, 51 process indicators, and 4 outcome indicators).

Phase 3: Delphi Consensus ProcessThe preliminary set of 79 indicators (Table 1) approved by the multidisciplinary group was analyzed by the Delphi panel (31 dermatologists) in the first round of the consensus process.

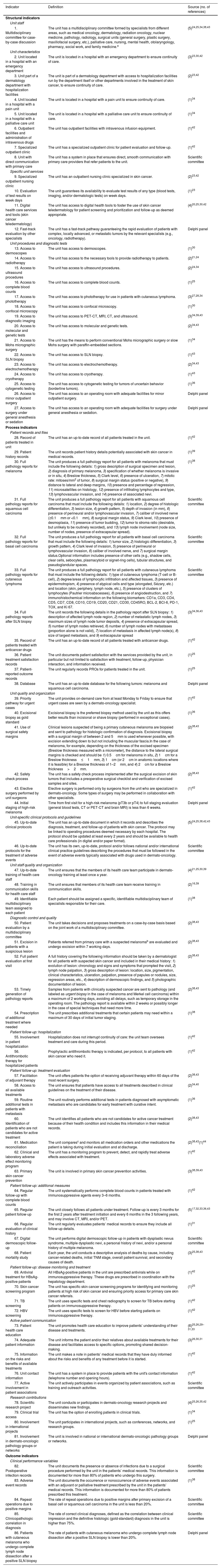

Quality Indicators Evaluated by Delphi Panel.

| Indicator | Definition | Source (no. of references) |

|---|---|---|

| Structural indicators | ||

| Unit staff | ||

| 1. Multidisciplinary committee for case-by-case discussion | The unit has a multidisciplinary committee formed by specialists from different areas, such as medical oncology, dermatology, radiation oncology, nuclear medicine, pathology, radiology, surgical units (general surgery, plastic surgery, maxillofacial surgery, etc.), palliative care, nursing, mental health, otolaryngology, pharmacy, social work, and family medicine.a | (5)24,25,34,38,43 |

| Unit characteristics | ||

| 2. Unit located in a hospital with an emergency department | The unit is located in a hospital with an emergency department to ensure continuity of care. | (3)23,30,42 |

| 3. Unit part of a dermatology department with hospitalization facilities | The unit is part of a dermatology department with access to hospitalization facilities run by the department itself or other departments involved in the treatment of skin cancer, to ensure continuity of care. | (2)23,42 |

| 4. Unit located in a hospital with a pain unit | The unit is located in a hospital with a pain unit to ensure continuity of care. | (1)34 |

| 5. Unit located in a hospital with a palliative care unit | The unit is located in a hospital with a palliative care unit to ensure continuity of care. | (1)34 |

| 6. Outpatient facilities and administration of intravenous drugs | The unit has outpatient facilities with intravenous infusion equipment. | (1)42 |

| 7. Specialized outpatient clinic | The unit has a specialized outpatient clinic for patient evaluation and follow-up. | (1)42 |

| 8. Unit with direct communication with primary care | The unit has a system in place that ensures direct, smooth communication with primary care providers that refer patients to the unit. | Scientific committee |

| Specific unit services | ||

| 9. Specialized outpatient nursing clinic | The unit has an outpatient nursing clinic specialized in skin cancer. | (2)23,42 |

| 10. Evaluation of test results on week days | The unit guarantees its availability to evaluate test results of any type (blood tests, imaging, and/or dermatologic tests) on week days. | (1)23 |

| 11. Digital health care services and tools (skin cancer teledermatology) | The unit has access to digital health tools to foster the use of skin cancer teledermatology for patient screening and prioritization and follow-up as deemed appropriate. | (4)20,25,30,42 |

| 12. Fast-track evaluation by other specialists | The unit has a fast-track pathway guaranteeing the rapid evaluation of patients with complex, locally advanced, or metastatic tumors by the relevant specialists (e.g., oncology, radiotherapy). | Delphi panel |

| Unit procedures and diagnostic tests | ||

| 13. Access to dermoscopes | The unit has access to dermoscopes. | (1)30 |

| 14. Access to radiotherapy | The unit has access to the necessary tools to provide radiotherapy to patients. | (2)21,24 |

| 15. Access to ultrasound procedures | The unit has access to ultrasound procedures. | (2)24,34 |

| 16. Access to complete blood counts | The unit has access to complete blood counts. | (1)25 |

| 17. Access to phototherapy | The unit has access to phototherapy for use in patients with cutaneous lymphoma. | (3)27,28,34 |

| 18. Access to confocal microscopy | The unit has access to confocal microscopy. | (1)30 |

| 19. Access to diagnostic imaging | The unit has access to PET-CT, MRI, CT, and ultrasound. | (3)34,39,43 |

| 20. Access to molecular and genetic tests | The unit has access to molecular and genetic tests. | (2)34,43 |

| 21. Access to Mohs micrographic surgery | The unit has the means to perform conventional Mohs micrographic surgery or slow Mohs surgery with paraffin-embedded sections. | (1)34 |

| 22. Access to SLN biopsy | The unit has access to SLN biopsy. | (1)43 |

| 23. Access to electrochemotherapy | The unit has access to electrochemotherapy. | (2)34,43 |

| 24. Access to cryotherapy | The unit has access to cryotherapy. | (1)43 |

| 25. Access to cytogenetic testing | The unit has access to cytogenetic testing for tumors of uncertain behavior (borderline tumors). | (1)36 |

| 26. Access to minor outpatient surgery | The unit has access to an operating room with adequate facilities for minor outpatient surgery. | Delphi panel |

| 27. Access to surgery under general anesthesia or sedation | The unit has access to an operating room with adequate facilities for surgery under general anesthesia or sedation. | Delphi panel |

| Process indicators | ||

| Patient records and files | ||

| 28. Record of patients treated in unit | The unit has an up-to-date record of all patients treated in the unit. | (1)42 |

| 29. Patient history records | The unit records patient history details potentially associated with skin cancer in medical records. | (1)39 |

| 30. Full pathology reports for melanoma | The unit produces a full pathology report for all patients with melanoma that must include the following details: 1) gross description of surgical specimen and lesion, 2) diagnosis of primary melanoma, 3) specification of whether melanoma is invasive or in situ, 4) Breslow thickness, 5) Clark level, 6) presence of ulceration, 7) mitotic rate: mitoses/mm2 of tumor, 8) surgical margin status (positive or negative), 9) distance to lateral and deep margins, 10) presence and percentage of regression, 11) microsatellites on histology, 12) presence of infiltrating lymphocytes and type, 13) lymphovascular invasion, and 14) presence of associated nevi. | (1)38 |

| 31. Full pathology reports for squamous cell carcinoma | The unit produces a full pathology report for all patients with squamous cell carcinoma that must include the following details: 1) location, 2) degree of histologic differentiation, 3) lesion size, 4) growth pattern, 5) depth of invasion (in mm), 6) presence of perineural and/or lymphovascular invasion, 7) caliber of involved nerve (≥0.1mm or <0.1mm), 8) surgical margin status, 9) Clark level, 10) presence of desmoplasia, 11) presence of tumor budding, 12) tumor to stroma ratio (desirable, but unlikely to be routinely recorded), and 13) lymph node involvement (node size, number of nodes, presence of extracapsular spread). | Scientific committee |

| 32. Full pathology reports for basal cell carcinoma | The unit produces a full pathology report for all patients with basal cell carcinoma that must include the following details: 1) tumor size, 2) histologic differentiation, 3) growth pattern, 4) Clark level of invasion, 5) presence of perineural or lymphovascular invasion, 6) caliber of involved nerve, and 7) surgical margin status.Optional information includes presence of other cells (e.g., shadow cells, clear cells, sebocytes, plasmacytoid or signet-ring cells), tubular structures, and pseudoglandular spaces. | Scientific committee |

| 33. Full pathology reports for cutaneous lymphoma | The unit produces a full pathology report for all patients with cutaneous lymphoma that must include the following details: 1) type of cutaneous lymphoma (T-cell or B-cell), 2) degree/areas of lymphocytic infiltration and affected tissues, 3) presence of epidermotropism, 4) presence of atypical cells and type (elongated, Sézary, etc.) and location (skin, periphery, lymph node, etc.), 5) presence of clusters of lymphocytes (Pautrier microabscesses), 6) presence of angiodestruction, and 7) immunohistochemical information on the following biomarkers: CD1a, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7, CD8, CD10, CD19, CD20, CD21, CD30, CD45RO, BCL-2, BCl-6, PD-1, TOX, and Ki 67. | Scientific committee |

| 34. Full pathology reports after SLN biopsy | The unit records the following details in the pathology report after SLN biopsy: 1) description of affected lymph node region, 2) number of metastatic lymph nodes, 3) maximum sizes of lymph node tumor deposits, 4) presence of extracapsular spread, 5) number of lymph nodes retrieved, 6) number of lymph nodes with metastases (proportion alone is not valid), 7) location of metastasis in affected lymph node(s), 8) size of largest metastasis, and 9) extracapsular spread | (3)34,36,43 |

| 35. Record of patients treated with anticancer drugs | The unit has an up-to-date record of all patients treated with anticancer drugs. | (1)42 |

| 36. Patient treatment satisfaction records | The unit documents patient satisfaction with the services provided by the unit, in particular but not limited to satisfaction with treatment, follow-up, physician interaction, and information received. | (1)25 |

| 37. Patient-reported outcome records | The unit regularly records PROs for patients treated in the unit. | (1)25 |

| 38. Database | The unit has an up-to-date database for the following tumors: melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma. | Delphi panel |

| Unit quality and organization | ||

| 39. Priority pathway for urgent cases | The unit provides on-demand care from at least Monday to Friday to ensure that urgent cases are seen by a dermato-oncology specialist. | (1)42 |

| 40. Excisional biopsy as gold standard | Excisional biopsy is the preferred biopsy method used by the unit as this offers better results than incisional or shave biopsy (performed in exceptional cases). | (1)36 |

| 41. Use of surgical safety margins | Clinical lesions suspected of being a primary cutaneous melanoma are biopsied and sent to pathology for histologic confirmation of diagnosis. Excisional biopsy with a surgical margin of between 2 and 5mm is used whenever possible, with excision extending down to but not including the muscular fascia.In the case of melanoma, for example, depending on the thickness of the excised specimen (Breslow thickness measured with a micrometer), the distance to the lateral surgical margins is checked and should be 1) 0.5cm for melanoma in situ, 2) 1cm for a Breslow thickness≤1mm, 3) 1cm (or 2cm in anatomic locations where it is feasible) for a Breslow thickness of 1–2mm, and 4) 2cm for a Breslow thickness>2mm. | (2)38,43 |

| 42. Safety check process | The unit has a safety check process implemented after the surgical excision of skin tumors that includes a preoperative surgical checklist and verification of excised samples and sites. | (2)38,43 |

| 43. Elective surgery performed by unit surgeons | Elective surgery is performed only by surgeons from the unit who are specialized in dermato-oncology. Some types of surgery may be performed in collaboration with other specialists. | (1)42 |

| 44. Initial staging of high-risk melanoma | Time from first visit for a high-risk melanoma (pT3b or pT4) to full staging evaluation (general blood tests, CT or PET-CT and brain MRI) is less than 6 weeks. | Delphi panel |

| Unit-specific clinical protocols and guidelines | ||

| 45. Up-to-date clinical protocols | The unit has an up-to-date document in which it records and describes the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of patients with skin cancer. The protocol may be linked to operating procedures deemed necessary by each hospital. The protocol should be updated at least every 2 years and should be available to health care professionals (in digital and/or paper format). | (5)24,25,38,42,43 |

| 46. Up-to-date protocols for the treatment of adverse events | The unit has its own, up-to-date, protocol and/or follows national and/or international clinical practice guidelines describing the procedures that must be followed in the event of adverse events typically associated with drugs used in dermato-oncology. | Scientific committee |

| Unit staff quality and organization | ||

| 47. Up-to-date training of health care staff | The unit ensures that the members of its health care team participate in dermato-oncology training at least once a year. | (4)21,25,30,39 |

| 48. Training in communication skills for health care staff | The unit ensures that members of its health care team receive training in communication skills. | (2)16,39 |

| 49. Identifiable multidisciplinary team assigned to each patient | Each patient should be assigned a specific, identifiable multidisciplinary team of specialists responsible for their care. | (1)38 |

| Diagnostic control and quality | ||

| 50. Patient evaluation by a multidisciplinary committee | The unit takes decisions and proposes treatments on a case-by-case basis based on the joint work of a multidisciplinary committee. | (2)38,43 |

| 51. Excision in patients with a suspicious lesion | Patients referred from primary care with a suspected melanomab are evaluated and undergo excision within 7 working days. | (2)38,43 |

| 52. Full patient evaluation at first visit | A full history covering the following information should be taken by a dermatologist for all patients with suspected skin cancer and included in their medical history: 1) evolution of lesion: chronology and signs and symptoms that prompted the visit, 2) lymph node palpation, 3) gross description of lesion: location, size, pigmentation, clinical characteristics, ulceration, palpation, presence of papules or nodules, size, regression areas, etc., 4) description of dermoscopic findings, and 5) photographic documentation of lesion. | (2)38,43 |

| 53. Timely generation of pathology reports | Samples from patients with clinically suspected cancer are sent to pathology (and labeled as urgent biopsy in the case of melanoma and Merkel cell carcinoma) within a maximum of 2 working days, avoiding all delays, such as temporary storage in the operating room. The pathology report is available within 2 weeks or possibly longer in the case of special techniques that need more time. | (2)38,43 |

| 54. Prescription of additional treatment where needed | The unit prescribes additional treatments that certain patients may need within a maximum of 30 days of initial tumor staging. | (1)38 |

| Patient follow-up: hospitalization | ||

| 55. Involvement in patient hospitalization | Hospitalization does not interrupt continuity of care: the unit team oversees treatment and care during this period. | (1)42 |

| 56. Antithrombotic therapy for hospitalized patients | Prophylactic antithrombotic therapy is indicated, per protocol, to all patients with skin cancer who need it. | (1)42 |

| Patient follow-up: treatment evaluation | ||

| 57. Facilitation of adjuvant therapy | The unit offers patients the option of receiving adjuvant therapy within 60 days of the most recent surgery. | (2)38,43 |

| 58. Access to all available treatments | The unit ensures that patients have access to all treatments described in clinical guidelines on the treatment of their disease. | (2)34,40 |

| 59. Routine additional tests in patients with metastasis | The unit routinely performs additional tests in patients diagnosed with asymptomatic metastasis who are candidates for early treatment with curative intent. | (1)36 |

| 60. Identification of patients who are not candidates for active treatment | The unit identifies all patients who are not candidates for active cancer treatment because of their health condition and includes this information in their medical records. | (2)38,43 |

| 61. Medication reconciliation | The unit comparesc and monitors all medication orders and other medications the patient is taking during initial evaluation and at discharge. | (2)38,43(1)44 |

| 62. Clinical and laboratory adverse effect monitoring program | The unit has a monitoring program to prevent, detect, and rapidly treat adverse effects associated with treatment. | (1)42 |

| 63. Primary skin cancer prevention | The unit is involved in primary skin cancer prevention activities. | (3)38,39,43 |

| Patient follow-up: additional measures | ||

| 64. Regular follow-up with complete blood counts | The unit systematically performs complete blood counts in patients treated with immunosuppressive agents every 3–6 months. | (1)42 |

| 65. Regular patient follow-up | The unit closely follows all patients under treatment. Follow-up is every 3 months for the first 2 years after treatment initiation and every 6 months in the 3 following years, and may involve CT, MRI, and/or PET. | (5)17,32,33,36,43 |

| 66. Regular evaluation of clinical history | The unit regularly evaluates patients’ medical records to ensure they include all follow-up details. | (1)31 |

| 67. Digital dermoscopic follow-up | The unit performs digital dermoscopic follow-up in patients with dysplastic nevus syndrome, multiple dysplastic nevi, a personal history of nevi, and/or a personal history of multiple melanoma. | Scientific committee |

| 68. Patient mortality study | Each year, the unit conducts a descriptive analysis of deaths by cause, including cancer-related deaths, initial TNM stage, overall patient survival, and secondary causes of death. | (3)25,38,43 |

| Patient follow-up: disease monitoring and treatment | ||

| 69. Antiviral treatment for HBsAg-positive patients | All HBsAg-positive patients in the unit are prescribed antivirals while on immunosuppressive therapy. These drugs are prescribed in coordination with the hepatology department. | (1)42 |

| 70. Skin cancer screening program | The unit has specific skin cancer screening programs for identifying and monitoring patients at high risk of skin cancer and ensuring priority access for primary care skin cancer referrals. | (1)25 |

| 71. TB screening | The unit uses specific tests and chest radiography to screen for TB before starting patients on immunosuppressive therapy. | (1)42 |

| 72. HBV screening | The unit uses specific tests to screen for HBV before starting patients on immunosuppressive therapy. | (1)42 |

| Active patient communication | ||

| 73. Patient health care education | The unit promotes health care education to improve patients’ understanding of their disease and treatments. | (6)25,26,29–31,33 |

| 74. Adequate patient information | The unit informs the patient and/or their relatives about available treatments for their disease and facilitates access to specific options, promoting shared decision-making. | (3)26,30,31 |

| 75. Information on the risks and benefits of available treatments | The unit makes a note in patients’ medical records that they have duly informed about the risks and benefits of any treatment before it is started. | (1)42 |

| 76. Unit contact information | The unit has a system in place to provide patients with the unit's contact information (telephone number and opening hours). | (1)42 |

| 77. Active involvement in patient associations | The unit actively participates in events organized by patient associations, such as training and outreach activities. | Scientific committee |

| Research contributions | ||

| 78. Scientific research project | The unit conducts or participates in dermato-oncology research projects and disseminates new findings. | (4)25,26,35,42 |

| 79. Clinical trial access | The unit has the option of enrolling patients in clinical trials. | (1)34 |

| 80. Involvement in international projects | The unit participates in international projects, such as conferences, networks, and research groups. | (1)25 |

| 81. Involvement in dermato-oncologic pathology groups or networks | The unit is involved in national or international dermato-oncologic pathology groups or networks. | Delphi panel |

| Outcome indicators | ||

| Clinical performance variables | ||

| 82. Postoperative infection records | The unit documents the presence or absence of infections due to a surgical procedure performed by the unit in the patients’ medical records. This information is documented for more than 80% of patients who undergo this surgery. | Scientific committee |

| 83. Adverse event records | The unit documents the occurrence or nonoccurrence of adverse events associated with an adjuvant or palliative treatment prescribed by the unit in the patients’ medical records. This information is documented for more than 80% of patients prescribed this treatment. | (1)38 |

| 84. Repeat operations due to positive margins | The rate of repeat operations due to positive margins after primary excision of a basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma in the unit is less than 20%. | Scientific committee |

| 85. Clinicopathologic correlation in diagnosis | The rate of correct clinical diagnoses, defined as the correlation between clinical impression and the definitive histologic (gold-standard) diagnosis in the unit is higher than 75%. | Scientific committee |

| 86. Patients with cutaneous melanoma who undergo complete lymph node dissection after a positive SLN biopsy | The rate of patients with cutaneous melanoma who undergo complete lymph node dissection after a positive SLN biopsy is lower than 20%. | Delphi panel |

CT, computed tomography; HbsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; PET, positron emission tomography; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SLN, sentinel lymph node; TB, tuberculosis.

The specialists forming the multidisciplinary committee will vary according to the dermato-oncologic disease(s) involved.

A lesion is considered suspicious for melanoma if it meets 1 or more of the ABCDEF criteria, where A indicates asymmetry of shape; B, border irregularity (irregular, jagged borders); C, color variability, D, diameter>0.6cm; E, evolving (sudden change in size, color, or thickness); and F, different or “ugly duckling” lesion (pigmented lesion that is different to other lesions in the same patient).

Formal process in which the hospital pharmacist compares a complete, accurate list of medications the patient has taken with new drugs ordered after the care transition. Duplicate medications or drug–drug interactions between chronic and newly ordered treatments at the hospital should be discussed with the physician, and where necessary, the prescription modified.

Seven new indicators (3 for structure, 3 for process, and 1 for outcome) were added after the first round, giving a total of 86 second-round indicators (Table 1). This round was completed by 28 dermatologists.

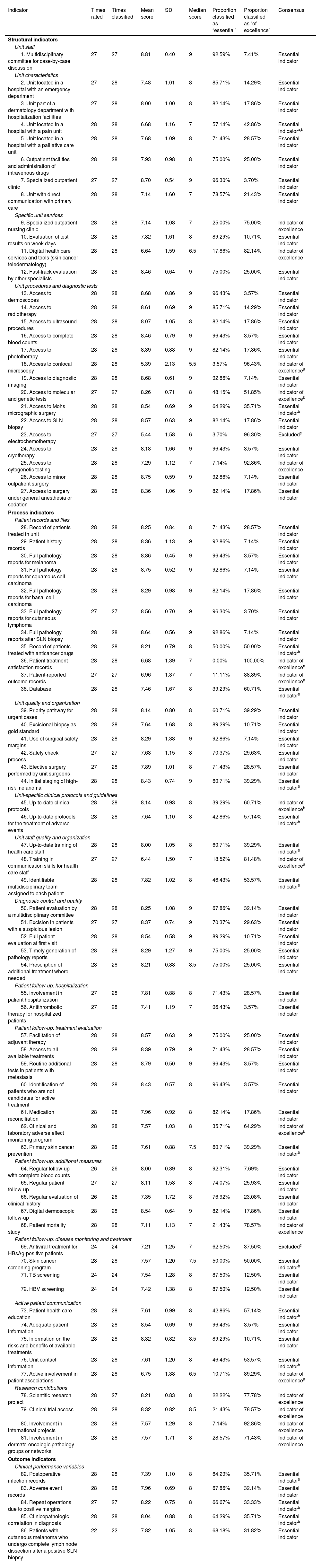

The scores assigned in the second round, together with the levels of consensus on the inclusion or exclusion of indicators and their classification as “essential” or “of excellence” are shown in Table 2.

Results of the Delphi Consensus Process.

| Indicator | Times rated | Times classified | Mean score | SD | Median score | Proportion classified as “essential” | Proportion classified as “of excellence” | Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural indicators | ||||||||

| Unit staff | ||||||||

| 1. Multidisciplinary committee for case-by-case discussion | 27 | 27 | 8.81 | 0.40 | 9 | 92.59% | 7.41% | Essential indicator |

| Unit characteristics | ||||||||

| 2. Unit located in a hospital with an emergency department | 27 | 28 | 7.48 | 1.01 | 8 | 85.71% | 14.29% | Essential indicator |

| 3. Unit part of a dermatology department with hospitalization facilities | 27 | 28 | 8.00 | 1.00 | 8 | 82.14% | 17.86% | Essential indicator |

| 4. Unit located in a hospital with a pain unit | 28 | 28 | 6.68 | 1.16 | 7 | 57.14% | 42.86% | Essential indicatora,b |

| 5. Unit located in a hospital with a palliative care unit | 28 | 28 | 7.68 | 1.09 | 8 | 71.43% | 28.57% | Essential indicator |

| 6. Outpatient facilities and administration of intravenous drugs | 28 | 28 | 7.93 | 0.98 | 8 | 75.00% | 25.00% | Essential indicator |

| 7. Specialized outpatient clinic | 27 | 27 | 8.70 | 0.54 | 9 | 96.30% | 3.70% | Essential indicator |

| 8. Unit with direct communication with primary care | 28 | 28 | 7.14 | 1.60 | 7 | 78.57% | 21.43% | Essential indicator |

| Specific unit services | ||||||||

| 9. Specialized outpatient nursing clinic | 28 | 28 | 7.14 | 1.08 | 7 | 25.00% | 75.00% | Indicator of excellence |

| 10. Evaluation of test results on week days | 28 | 28 | 7.82 | 1.61 | 8 | 89.29% | 10.71% | Essential indicator |

| 11. Digital health care services and tools (skin cancer teledermatology) | 28 | 28 | 6.64 | 1.59 | 6.5 | 17.86% | 82.14% | Indicator of excellence |

| 12. Fast-track evaluation by other specialists | 28 | 28 | 8.46 | 0.64 | 9 | 75.00% | 25.00% | Essential indicator |

| Unit procedures and diagnostic tests | ||||||||

| 13. Access to dermoscopes | 28 | 28 | 8.68 | 0.86 | 9 | 96.43% | 3.57% | Essential indicator |

| 14. Access to radiotherapy | 28 | 28 | 8.61 | 0.69 | 9 | 85.71% | 14.29% | Essential indicator |

| 15. Access to ultrasound procedures | 28 | 28 | 8.07 | 1.05 | 8 | 82.14% | 17.86% | Essential indicator |

| 16. Access to complete blood counts | 28 | 28 | 8.46 | 0.79 | 9 | 96.43% | 3.57% | Essential indicator |

| 17. Access to phototherapy | 28 | 28 | 8.39 | 0.88 | 9 | 82.14% | 17.86% | Essential indicator |

| 18. Access to confocal microscopy | 28 | 28 | 5.39 | 2.13 | 5.5 | 3.57% | 96.43% | Indicator of excellencea |

| 19. Access to diagnostic imaging | 28 | 28 | 8.68 | 0.61 | 9 | 92.86% | 7.14% | Essential indicator |

| 20. Access to molecular and genetic tests | 27 | 27 | 8.26 | 0.71 | 8 | 48.15% | 51.85% | Indicator of excellenceb |

| 21. Access to Mohs micrographic surgery | 28 | 28 | 8.54 | 0.69 | 9 | 64.29% | 35.71% | Essential indicatorb |

| 22. Access to SLN biopsy | 28 | 28 | 8.57 | 0.63 | 9 | 82.14% | 17.86% | Essential indicator |

| 23. Access to electrochemotherapy | 27 | 27 | 5.44 | 1.58 | 6 | 3.70% | 96.30% | Excludedc |

| 24. Access to cryotherapy | 28 | 28 | 8.18 | 1.66 | 9 | 96.43% | 3.57% | Essential indicator |

| 25. Access to cytogenetic testing | 28 | 28 | 7.29 | 1.12 | 7 | 7.14% | 92.86% | Indicator of excellence |

| 26. Access to minor outpatient surgery | 28 | 28 | 8.75 | 0.59 | 9 | 92.86% | 7.14% | Essential indicator |

| 27. Access to surgery under general anesthesia or sedation | 28 | 28 | 8.36 | 1.06 | 9 | 82.14% | 17.86% | Essential indicator |

| Process indicators | ||||||||

| Patient records and files | ||||||||

| 28. Record of patients treated in unit | 28 | 28 | 8.25 | 0.84 | 8 | 71.43% | 28.57% | Essential indicator |

| 29. Patient history records | 28 | 28 | 8.36 | 1.13 | 9 | 92.86% | 7.14% | Essential indicator |

| 30. Full pathology reports for melanoma | 28 | 28 | 8.86 | 0.45 | 9 | 96.43% | 3.57% | Essential indicator |

| 31. Full pathology reports for squamous cell carcinoma | 28 | 28 | 8.75 | 0.52 | 9 | 92.86% | 7.14% | Essential indicator |

| 32. Full pathology reports for basal cell carcinoma | 28 | 28 | 8.29 | 0.98 | 9 | 82.14% | 17.86% | Essential indicator |

| 33. Full pathology reports for cutaneous lymphoma | 27 | 27 | 8.56 | 0.70 | 9 | 96.30% | 3.70% | Essential indicator |

| 34. Full pathology reports after SLN biopsy | 28 | 28 | 8.64 | 0.56 | 9 | 92.86% | 7.14% | Essential indicator |

| 35. Record of patients treated with anticancer drugs | 28 | 28 | 8.21 | 0.79 | 8 | 50.00% | 50.00% | Essential indicatorb |

| 36. Patient treatment satisfaction records | 28 | 28 | 6.68 | 1.39 | 7 | 0.00% | 100.00% | Indicator of excellencea |

| 37. Patient-reported outcome records | 27 | 27 | 6.96 | 1.37 | 7 | 11.11% | 88.89% | Indicator of excellencea |

| 38. Database | 28 | 28 | 7.46 | 1.67 | 8 | 39.29% | 60.71% | Essential indicatorb |

| Unit quality and organization | ||||||||

| 39. Priority pathway for urgent cases | 28 | 28 | 8.14 | 0.80 | 8 | 60.71% | 39.29% | Essential indicator |

| 40. Excisional biopsy as gold standard | 28 | 28 | 7.64 | 1.68 | 8 | 89.29% | 10.71% | Essential indicator |

| 41. Use of surgical safety margins | 28 | 28 | 8.29 | 1.38 | 9 | 92.86% | 7.14% | Essential indicator |

| 42. Safety check process | 27 | 27 | 7.63 | 1.15 | 8 | 70.37% | 29.63% | Essential indicator |

| 43. Elective surgery performed by unit surgeons | 27 | 28 | 7.89 | 1.01 | 8 | 71.43% | 28.57% | Essential indicator |

| 44. Initial staging of high-risk melanoma | 28 | 28 | 8.43 | 0.74 | 9 | 60.71% | 39.29% | Essential indicatorb |

| Unit-specific clinical protocols and guidelines | ||||||||

| 45. Up-to-date clinical protocols | 28 | 28 | 8.14 | 0.93 | 8 | 39.29% | 60.71% | Indicator of excellenceb |

| 46. Up-to-date protocols for the treatment of adverse events | 28 | 28 | 7.64 | 1.10 | 8 | 42.86% | 57.14% | Essential indicatorb |

| Unit staff quality and organization | ||||||||

| 47. Up-to-date training of health care staff | 28 | 28 | 8.00 | 1.05 | 8 | 60.71% | 39.29% | Essential indicatorb |

| 48. Training in communication skills for health care staff | 27 | 27 | 6.44 | 1.50 | 7 | 18.52% | 81.48% | Indicator of excellencea |

| 49. Identifiable multidisciplinary team assigned to each patient | 28 | 28 | 7.82 | 1.02 | 8 | 46.43% | 53.57% | Essential indicatorb |

| Diagnostic control and quality | ||||||||

| 50. Patient evaluation by a multidisciplinary committee | 28 | 28 | 8.25 | 1.08 | 9 | 67.86% | 32.14% | Essential indicator |

| 51. Excision in patients with a suspicious lesion | 27 | 27 | 8.37 | 0.74 | 9 | 70.37% | 29.63% | Essential indicator |

| 52. Full patient evaluation at first visit | 28 | 28 | 8.54 | 0.58 | 9 | 89.29% | 10.71% | Essential indicator |

| 53. Timely generation of pathology reports | 28 | 28 | 8.29 | 1.27 | 9 | 75.00% | 25.00% | Essential indicator |

| 54. Prescription of additional treatment where needed | 28 | 28 | 8.21 | 0.88 | 8.5 | 75.00% | 25.00% | Essential indicator |

| Patient follow-up: hospitalization | ||||||||

| 55. Involvement in patient hospitalization | 27 | 28 | 7.81 | 0.88 | 8 | 71.43% | 28.57% | Essential indicator |

| 56. Antithrombotic therapy for hospitalized patients | 27 | 28 | 7.41 | 1.19 | 7 | 96.43% | 3.57% | Essential indicator |

| Patient follow-up: treatment evaluation | ||||||||

| 57. Facilitation of adjuvant therapy | 28 | 28 | 8.57 | 0.63 | 9 | 75.00% | 25.00% | Essential indicator |

| 58. Access to all available treatments | 28 | 28 | 8.39 | 0.79 | 9 | 71.43% | 28.57% | Essential indicator |

| 59. Routine additional tests in patients with metastasis | 28 | 28 | 8.79 | 0.50 | 9 | 96.43% | 3.57% | Essential indicator |

| 60. Identification of patients who are not candidates for active treatment | 28 | 28 | 8.43 | 0.57 | 8 | 96.43% | 3.57% | Essential indicator |

| 61. Medication reconciliation | 28 | 28 | 7.96 | 0.92 | 8 | 82.14% | 17.86% | Essential indicator |

| 62. Clinical and laboratory adverse effect monitoring program | 28 | 28 | 7.57 | 1.03 | 8 | 35.71% | 64.29% | Indicator of excellenceb |

| 63. Primary skin cancer prevention | 28 | 28 | 7.61 | 0.88 | 7.5 | 60.71% | 39.29% | Essential indicatorb |

| Patient follow-up: additional measures | ||||||||

| 64. Regular follow-up with complete blood counts | 26 | 26 | 8.00 | 0.89 | 8 | 92.31% | 7.69% | Essential indicator |

| 65. Regular patient follow-up | 27 | 27 | 8.11 | 1.53 | 8 | 74.07% | 25.93% | Essential indicator |

| 66. Regular evaluation of clinical history | 26 | 26 | 7.35 | 1.72 | 8 | 76.92% | 23.08% | Essential indicator |

| 67. Digital dermoscopic follow-up | 28 | 28 | 8.54 | 0.64 | 9 | 82.14% | 17.86% | Essential indicator |

| 68. Patient mortality study | 28 | 28 | 7.11 | 1.13 | 7 | 21.43% | 78.57% | Indicator of excellence |

| Patient follow-up: disease monitoring and treatment | ||||||||

| 69. Antiviral treatment for HBsAg-positive patients | 24 | 24 | 7.21 | 1.25 | 7 | 62.50% | 37.50% | Excludedc |

| 70. Skin cancer screening program | 28 | 28 | 7.57 | 1.20 | 7.5 | 50.00% | 50.00% | Essential indicatorb |

| 71. TB screening | 24 | 24 | 7.54 | 1.28 | 8 | 87.50% | 12.50% | Essential indicator |

| 72. HBV screening | 24 | 24 | 7.42 | 1.38 | 8 | 87.50% | 12.50% | Essential indicator |

| Active patient communication | ||||||||

| 73. Patient health care education | 28 | 28 | 7.61 | 0.99 | 8 | 42.86% | 57.14% | Essential indicatorb |

| 74. Adequate patient information | 28 | 28 | 8.54 | 0.69 | 9 | 96.43% | 3.57% | Essential indicator |

| 75. Information on the risks and benefits of available treatments | 28 | 28 | 8.32 | 0.82 | 8.5 | 89.29% | 10.71% | Essential indicator |

| 76. Unit contact information | 28 | 28 | 7.61 | 1.20 | 8 | 46.43% | 53.57% | Essential indicatorb |

| 77. Active involvement in patient associations | 28 | 28 | 6.75 | 1.38 | 6.5 | 10.71% | 89.29% | Indicator of excellencea |

| Research contributions | ||||||||

| 78. Scientific research project | 28 | 27 | 8.21 | 0.83 | 8 | 22.22% | 77.78% | Indicator of excellence |

| 79. Clinical trial access | 28 | 28 | 8.32 | 0.82 | 8.5 | 21.43% | 78.57% | Indicator of excellence |

| 80. Involvement in international projects | 28 | 28 | 7.57 | 1.29 | 8 | 7.14% | 92.86% | Indicator of excellence |

| 81. Involvement in dermato-oncologic pathology groups or networks | 28 | 28 | 7.57 | 1.71 | 8 | 28.57% | 71.43% | Indicator of excellence |

| Outcome indicators | ||||||||

| Clinical performance variables | ||||||||

| 82. Postoperative infection records | 28 | 28 | 7.39 | 1.10 | 8 | 64.29% | 35.71% | Essential indicatorb |

| 83. Adverse event records | 28 | 28 | 7.96 | 0.69 | 8 | 67.86% | 32.14% | Essential indicator |

| 84. Repeat operations due to positive margins | 27 | 27 | 8.22 | 0.75 | 8 | 66.67% | 33.33% | Essential indicatorb |

| 85. Clinicopathologic correlation in diagnosis | 28 | 28 | 8.04 | 0.88 | 8 | 64.29% | 35.71% | Essential indicatorb |

| 86. Patients with cutaneous melanoma who undergo complete lymph node dissection after a positive SLN biopsy | 22 | 22 | 7.82 | 1.05 | 8 | 68.18% | 31.82% | Essential indicator |

HBsAG, hepatitis B surface antigen; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SLN, sentinel lymph node; TB, tuberculosis.

Consensus was obtained for 84 indicators (26 structural indicators, 53 process indicators, and 5 outcome indicators). Sixty-eight were classified as being essential and 16 as indicative of excellence.

DiscussionThe CUDERMA project was designed to establish the minimum standards a functional dermatology unit must meet in order to guarantee quality and consistency in health care. This study describes the first phase of the project, designed to achieve consensus on core indicators for measuring a unit's ability to deliver proper treatment and follow-up care to dermato-oncology patients.

Some of the characteristics classified as essential by the Delphi panelists were a) presence of a multidisciplinary committee to manage patients, b) access to hospitalization and emergency services within the dermatology department or hospital, c) access to procedures and treatments considered essential for the treatment of skin cancer, d) production of full pathology reports on different types of tumors, e) processes that guarantee surgical safety, and f) adherence to predefined procedure times.

Characteristics indicative of excellence included a) recording of patient-reported outcomes, such as quality of life and treatment satisfaction, b) staff training in communication skills, and c) research.

Although the CUDERMA project has produced the first set of indicators for the certification of dermato-oncology units, other indicators have been developed in this field. The first Spanish initiative in this area was the 2012 Andalusian Society for Health Care Quality (SADECA) project in which a multidisciplinary committee of 14 experts used the nominal group technique to evaluate appropriate indicators from the literature to assess quality of care in melanoma.38 The CUDERMA project takes a broader approach as it seeks to cover all types of skin cancer. It also used a different consensus methodology: the Delphi technique. Another difference is that the SADECA initiative was exclusively designed to assess health care quality. The resulting set of indicators has been used by several projects to assess quality of care in cutaneous melanoma.39,43

Another Spanish study, conducted in 2015, evaluated adherence to structural indicators in dermato-oncology units using an online questionnaire in which the heads of dermatology departments answered questions on a range of aspects, such as availability of different techniques and treatments, access to tests and facilities, recording and reporting practices, and patient pathways.34

All the indicators described in the above studies were contemplated during the first phase of the CUDERMA project and included in the set of selected indicators. The main strength of the CUDERMA project compared with previous initiatives is its use of the Delphi consensus method, which provided a rigorous means for identifying potential indicators and allowed the participation of a large number of experts.

Another differentiating strength of the CUDERMA project is its classification of items as “essential” or “of excellence”. This distinction makes it possible to ensure consistency across units by establishing minimum certification standards, while also encouraging units with greater experience and resources to aspire to excellence.

Involvement of a multidisciplinary group also confers robustness to the first phase of the CUDERMA project. Input from other specialists involved in the management of skin cancer gave a broader perspective to the indicators selected. Although this multidisciplinary approach is a strength of this study, it should be noted that specialists from other fields participated in the preliminary evaluation phase, not on the Delphi panel. In view of this potential limitation, efforts were made to preserve their original contributions.

Finally, the CUDERMA project was designed to obtain consensus on measurable indicators and to define these indicators (name, definition, standard, objective level of compliance, and evidence of compliance) in 2 separate stages. The selected indicators will therefore be standardized for subsequent certification of units, demonstrating their relevance for guaranteeing quality of care in dermato-oncology.

ConclusionsThis first phase of the CUDERMA project generated consensus on aspects that should be covered by quality indicators used in the certification of dermato-oncology units. Examples of aspects that the dermatologists agreed were essential to the functioning of these units were involvement of a multidisciplinary committee in case management, access to a wide range of services, procedures, and treatments, production of full histology reports, implementation of processes to guarantee surgical safety, and adherence to predefined procedures times. Examples of excellence in practice were reporting of patient-reported outcomes and promotion of scientific research.

FundingThe CUDERMA project is an initiative of the AEDV and is funded by an unrestricted grant from Abbvie.

Research conducted at the Melanoma Unit of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona is partially funded by grants PI15/00716, PI15/00956, PI18/00959, PI22/01457, and PI18/00419 from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (Spain), the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) Biomedical Research Center for Rare Diseases (CIBER), cofunded by ISCII – Subdirección General de Evaluación and the European Regional Development Fund, A way to make Europe; AGAUR 2017 SGR 1134 and the CERCA program of the Generalitat de Catalunya (Spain); the European Commission under the 6th Framework Programme, Diagnoptics, and the European Commission under the HORIZON2020 Framework Programme, iTobos (965221), and Qualitop (875171); and the National Cancer Institute of the US National Institute of Health (CA83115). The project also received funding from TV3 Fundació La Marató through grants 201331-30 and 201923-30 (Catalonia, Spain) and the Fundación Científica de la Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (GCB15152978SOEN, Spain). Part of its work is conducted at Centro Esther Koplowitz (Barcelona).

Research activity conducted by Javier Cañueto is partially supported by grant GRS2139/A/20 (Gerencia Regional de Salud de Castilla y León) from ISCIII (PI21/01207), cofunded by the European Regional Development Fund and the Programa de Intensificación del ISCIII (grant number INT20/00074).

Conflicts of interestÍñigo Martínez de Espronceda Ezquerro has served on advisory boards for LEO Pharma and Sanofi. The sponsors had no role in study design or conduct; data collection, process, analysis, or interpretation; manuscript preparation, review, or approval; or the decision to submit for publication.

Sebastian Podlipnik has served on advisory boards for GalenicumDerma. The sponsor had no role in study design or conduct; data collection, process, analysis, or interpretation; manuscript preparation, review, or approval; or the decision to submit for publication.

Javier Cañueto has served on advisory boards for Almirall, Sanofi-Genzyme, Hoffman La Roche, Regeneron, and InflaRx. He has received speaker fees from Sanofi, Almirall, LEO Pharma, Abbvie, SunPharma, and Regeneron; he has received research funding from Castle Biosciences and Sanofi-Regeneron. The sponsors had no role in study design or conduct; data collection, process, analysis, or interpretation; manuscript preparation, review, or approval; or the decision to submit for publication.

Alberto de la Cuadra-Grande is an employee at Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Iberia (PORIB), a consultancy firm specialized in the economic evaluation of health interventions and health outcome research; he has received payment for methodological support throughout the project from AEDV.

Carlos Serra-Guillén, David Moreno, Lara Ferrándiz, Javier Domínguez-Cruz, Pablo de la Cueva, Yolanda Gilaberte, and Salvador Arias-Santiago declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this study.

The authors would like to thank Miguel Ángel Casado and Araceli Casado-Gómez, employees of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Iberia (PORIB), for their invaluable collaboration in this project.

Multidisciplinary group

Nuclear medicine. Gómez-Caminero, Felipe, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca; Vidal-Sicart, Sergi, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Medical oncology. García-Castaño, Almudena, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla; Muñoz-Couselo, Eva, Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain.

Radiation oncology. Jurado-Martín, Enrique, Hospital San Pedro de Logroño; Pérez-Romansanta, Luis Alberto, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain.

Pathology. Fernández-Flores, Ángel, Hospital del Bierzo; Ríos-Martín, Juan José, Hospital Virgen de la Macarena; Rodríguez-Peralto, José Luis, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain.

Diagnostic imaging. Arias-Rodríguez, Piedad, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca; Asensio-Calle, José Francisco, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain.

Consensus Group

Azcona-Rodríguez, Maialen, Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra; Bennassar, Antoni, Clínica Rotger, Grupo Quirón Salud; Boada-García, Aram, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Barcelona, Spain; Boix, Julián, Hospital de la Plana; Botella-Estrada, Rafael, Hospital la Fe de Valencia, Valencia, Spain; Carrera-Álvarez, Cristina, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Deza, Gustavo, Hospital del Mar, Institut Mar de Investigacions Mèdiques, Barcelona, Spain; Diago-Irache, Adrián, Hospital Universitario Miquel Servet, Zaragoza, Spain; Estrach, Maria Teresa, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Ferrándiz-Pulido, Carla, Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain; Fuente, María José, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Barcelona, Spain; Izu-Belloso, Rosa, Hospital Universitario de Basurto, Bilbao, Spain; Jaka, Ane, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Barcelona, Spain; Martí, Rosa María, Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida, Spain; Martínez-López, Antonio, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Granada, Spain; Nagore-Enguídanos, Eduardo, Instituto Valenciano de Oncología, Valencia, Spain; Oscoz-Jaime, Saioa, Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain; Paradela, Sabela, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña, Spain; Pujol i Vallverdú, Ramón M., Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, Spain; Redondo-Bellón, Pedro, Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain; Román-Curto, Concepción, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain; Tejera-Vaquerizo, Antonio, Hospital San Juan de Dios de Córdoba and Instituto Dermatológico GlobalDerm, Cordoba, Spain; Tercedor-Sánchez, Jesús, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Granada, Spain; Vázquez-Doval, Francisco Javier, Dermaclinic de Logroño, La Rioja, Spain; Vílchez-Márquez, Francisco Javier, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Granada, Spain; Yélamos, Oriol, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau and Centro Médico Teknon, Barcelona, Spain.

The members of the Multidisciplinary Group and the Delphi consensus panel are listed in Appendix 1.