The prevalence of obesity has increased worldwide in recent years. Some authors have described skin conditions associated with obesity, but there is little evidence on the association between insulin levels and such disorders.

ObjectiveTo describe the skin disorders present in overweight and obese patients and analyze their association with insulin levels.

Material and methodsThe study included nondiabetic male and female patients over 6 years of age who were seen at our hospital between January and April 2011. All the patients were evaluated by a dermatologist, who performed a physical examination, including anthropometry, and reviewed their medical history and medication record; fasting blood glucose and insulin were also measured. The patients were grouped according to degree of overweight or obesity and the data were compared using analysis of variance or the χ2 test depending on the type of variable. The independence of the associations was assessed using regression analysis.

ResultsIn total, 109 patients (95 adults and 13 children, 83.5% female) were studied. The mean (SD) age was 38 (14) years and the mean body mass index was 39.6±8kg/m2. The skin conditions observed were acanthosis nigricans (AN) (in 97% of patients), skin tags (77%), keratosis pilaris (42%), and plantar hyperkeratosis (38%). Statistically significant associations were found between degree of obesity and AN (P=.003), skin tags (P=.001), and plantar hyperkeratosis. Number of skin tags, AN neck severity score, and AN distribution were significantly and independently associated with insulin levels.

ConclusionsAN and skin tags should be considered clinical markers of hyperinsulinemia in nondiabetic, obese patients.

La prevalencia de obesidad se ha incrementado mundialmente en los últimos años. Existen estudios que describen las dermatosis que se asocian con la obesidad; sin embargo, existe poca evidencia de su asociación con los niveles de insulina.

ObjetivoDescribir las dermatosis presentes en pacientes con sobrepeso y obesidad y su asociación con los niveles de insulina.

Material y métodosSe incluyeron pacientes de ambos sexos, mayores de 6 años, no diabéticos que acudieron a la consulta durante los meses de enero a abril de 2011. Todos los sujetos fueron valorados por un dermatólogo, se realizó exploración física, antropometría, historia médica, medicamentos y medición de glucosa e insulina de ayuno. Los pacientes se dividieron de acuerdo a sobrepeso y grado de obesidad y se compararon con Anova o Chi cuadrado, dependiendo del tipo de variable. Se realizó análisis de regresión para evaluar la independencia de las asociaciones.

ResultadosFueron incluidos 109 pacientes (95 adultos y 13 niños; 83,5% mujeres), con edad media de 38±14 años y un índice de masa corporal de 39,6±8kg/m2. Las dermatosis encontradas fueron: acantosis nigricans (97%), fibromas (77%), queratosis pilar (42%) e hiperqueratosis plantar (38%). Las que se asociaron de forma estadísticamente significativa con el grado de obesidad fueron acantosis nigricans (p=0,003), fibromas (p=0,001) e hiperqueratosis plantar. El grado de acantosis nigricans en el cuello, su topografía y el número de fibromas mostraron asociación significativa e independiente con los niveles de insulina.

ConclusionesLa acantosis y los fibromas deberían considerarse marcadores clínicos de hiperinsulinemia en población obesa y no diabética.

The last 3 decades have seen an unprecedented increase in the prevalence of obesity throughout the world.1 In the United States of America, the prevalence of obesity is 35.5% in men, 35.8% in women,2 and 17% in children aged 2 to 19 years.3 In Mexico, the 2012 National Health Survey reported that the prevalence of obesity (body mass index [BMI]≥30kg/m2) in adults was 32.4% and the prevalence of overweight was 38.8% and that this prevalence was higher in women (37.5%) than in men (26.8%). The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity is only 3.6 percentage points greater in women (73.0%) than in men (69.4%); the combined prevalence for adolescents and adolescent males was 35.8% and 34.1%, respectively.4 Although obesity is considered a public health problem, it was recently recognized that rapid multidisciplinary action is necessary to ensure better prevention, timely diagnosis, and control.5,6 Obesity is accompanied by comorbid conditions such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, polycystic ovary syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, breast and colorectal cancer, psychological and orthopedic problems, and skin disorders.7

Dermatologic manifestations associated with obesity are common8,9 and have been classified according to their pathophysiologic origin as being associated with insulin resistance (IR), hyperandrogenism, skin folds, mechanical causes, and hospitalization.10,11 Several publications have shown the association between IR and acanthosis nigricans (AN) and skin tags both in adults12 and in children.13,14 The objectives of the present study were to identify skin disorders associated with obesity and to evaluate the correlation between insulin concentrations and skin disorders in nondiabetic overweight or obese individuals.

Materials and MethodsWe performed an analytical cross-sectional study including patients aged >6 years (patients aged >18 years were considered adults) of both sexes who attended the Obesity Clinic (bariatric surgery) and the Nutrition Clinic of Hospital General Dr. Manuel Gea González, Mexico City, Mexico from January to April 2011. All patients included in the study signed the informed consent document. All patients who were invited to participate agreed to do so. The Obesity Clinic handles patients who are candidates for bariatric surgery (BMI>40kg/m2 or>35kg/m2 accompanied by a comorbid condition). The Nutrition Clinic handles overweight and obese patients referred from other hospital departments. Patients with diabetes mellitus, pregnant women, and patients taking corticosteroids for more than 3 weeks were excluded, since each of these clinical conditions can be accompanied by specific skin disorders. Patients underwent a physical examination, and their clinical history was taken, with emphasis on previous diseases and anthropometric data (weight, height, waist circumference, and hip circumference). The skin examination aimed to identify lesions associated with hyperinsulinemia, namely, presence and degree of AN on the neck, AN at other sites, and presence and number of skin tags. The examination also included skin disorders associated with hyperandrogenism (acne, hirsutism, and androgenic alopecia), skin folds (intertrigo and bacterial complications), and mechanical causes (striae, lipodystrophy, plantar hyperkeratosis, and venous insufficiency). AN on the neck was graded according to the classification proposed by Burke et al.15: grade 0, absent; grade 1, detectable only on close visual inspection; grade II, <7.6cm in length (limited to the base of the skull); grade III, 7.6-15.2cm (extending to the lateral margins of the neck); and grade IV, >15.2cm (takes the form of a “collar” when viewed from the front). Fasting glucose and insulin (8h) were measured. Prediabetes was defined as fasting glucose of 100-125mg/dL and diabetes as fasting glucose >126mg/dL on at least 2 symptom-free occasions. BMI was calculated using the Quetelet formula (weight inkg divided by height inm2); the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the formula glucose in mmol/dL multiplied by insulin in μUI/mL divided by the constant 22.5.16 IR was defined arbitrarily as a HOMA-IR≥3. The World Health Organization classification was used for overweight and obesity both in children (2-18 years) and in adults (>18 years). In adults, overweight was defined as a BMI of 25-29.9, grade I obesity as a BMI of 30-34.9, grade II obesity as a BMI of 35-39.9, and grade III obesity as a BMI>40.17 In children, overweight was defined as a BMI≥the 85th percentile and lower than the 95th percentile, obesity as a BMI≥the 95th percentile, and severe obesity as a BMI>the 99th percentile.18 Hypercholesterolemia was defined as total cholesterol ≥200mg/dL, hypertriglyceridemia as triglycerides≥150mg/dL, hypoalfalipoproteinemia as high-density lipoprotein cholesterol<40mg/dL, and IR as a HOMA-IR index≥3.

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee.

Statistical AnalysisPatients were divided into 4 groups according to the presence of overweight and the degree of obesity. Quantitative variables were compared using parametric or nonparametric tests. The frequency of skin disorders was compared using the χ2 test for trend. Insulin concentrations were correlated with the grade of AN and the number of skin tags using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Multiple regression analysis was performed to evaluate the independence of the association between insulin and the number of skin tags; ordinal logistic regression was performed to evaluate the independence of the association between insulin and the grade of AN. Age, sex, and BMI were taken into consideration in both models. Statistical significance was set at P<.05. The analysis was performed using SPSS, version 19.0.

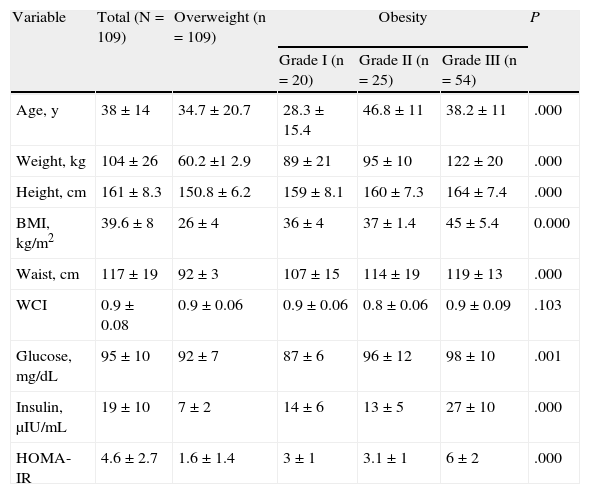

ResultsOur study included 109 patients (91 women [83.5%] and 18 men; 96 adults and 13 children). The mean (SD) values were as follows: age, 38 (14) years (range, 8-69 years); weight, 104 (26) kg; BMI, 39.6 (8); waist circumference, 117 (19) cm; and waist-hip index, 0.9 (0.08). About half of the patients (54 [49.5%]) met the criteria for grade III obesity. Patients with grade I obesity were significantly younger than those with grade II obesity (28.3 [15.4] vs 46.8 [11] years; P>.001). Significant differences were recorded for glucose, insulin, and the HOMA-IR index between the different grades of obesity (Table 1).

Clinical and Biochemical Characteristics According to Overweight and the Grade of Obesitya

| Variable | Total (N=109) | Overweight (n=109) | Obesity | P | ||

| Grade I (n=20) | Grade II (n=25) | Grade III (n=54) | ||||

| Age, y | 38±14 | 34.7±20.7 | 28.3±15.4 | 46.8±11 | 38.2±11 | .000 |

| Weight, kg | 104±26 | 60.2±1 2.9 | 89±21 | 95±10 | 122±20 | .000 |

| Height, cm | 161±8.3 | 150.8±6.2 | 159±8.1 | 160±7.3 | 164±7.4 | .000 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 39.6±8 | 26±4 | 36±4 | 37±1.4 | 45±5.4 | 0.000 |

| Waist, cm | 117±19 | 92±3 | 107±15 | 114±19 | 119±13 | .000 |

| WCI | 0.9±0.08 | 0.9±0.06 | 0.9±0.06 | 0.8±0.06 | 0.9±0.09 | .103 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 95±10 | 92±7 | 87±6 | 96±12 | 98±10 | .001 |

| Insulin, μIU/mL | 19±10 | 7±2 | 14±6 | 13±5 | 27±10 | .000 |

| HOMA-IR | 4.6±2.7 | 1.6±1.4 | 3±1 | 3.1±1 | 6±2 | .000 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; WCI, waist-circumference index.

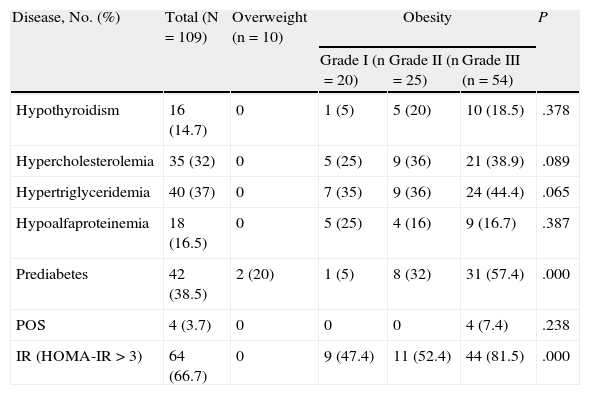

The frequency of prediabetes was 38.5%, which was greater in the grade III group (57.4%); this group also had a significantly greater frequency of IR (81.5%) than the overweight and grades I and II groups. The overweight group had 2 cases for which glucose values were compatible with a diagnosis of prediabetes, although no other comorbid conditions were recorded. No differences were recorded between the groups in the frequency of hypothyroidism, high total cholesterol and triglycerides, or low HDL cholesterol according to the grade of obesity (Table 2).

Frequency of Diseases Associated With Overweight and Grade of Obesitya

| Disease, No. (%) | Total (N=109) | Overweight (n=10) | Obesity | P | ||

| Grade I (n=20) | Grade II (n=25) | Grade III (n=54) | ||||

| Hypothyroidism | 16 (14.7) | 0 | 1 (5) | 5 (20) | 10 (18.5) | .378 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 35 (32) | 0 | 5 (25) | 9 (36) | 21 (38.9) | .089 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 40 (37) | 0 | 7 (35) | 9 (36) | 24 (44.4) | .065 |

| Hypoalfaproteinemia | 18 (16.5) | 0 | 5 (25) | 4 (16) | 9 (16.7) | .387 |

| Prediabetes | 42 (38.5) | 2 (20) | 1 (5) | 8 (32) | 31 (57.4) | .000 |

| POS | 4 (3.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (7.4) | .238 |

| IR (HOMA-IR>3) | 64 (66.7) | 0 | 9 (47.4) | 11 (52.4) | 44 (81.5) | .000 |

Abbreviations: HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; IR, insulin resistance; POS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

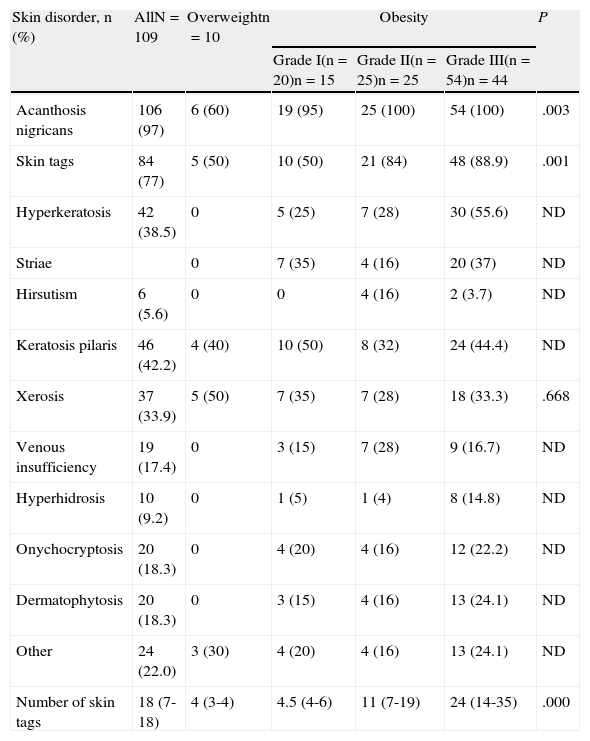

The frequency of skin disorders (Table 3) was as follows: AN, 97%; skin tags, 77%; keratosis pilaris, 42%; plantar hyperkeratosis, 38%; xerosis, 34%; and striae, 28%. The least frequent were palmoplantar hyperhidrosis (9%), hirsutism (5%), gynecomastia (3%), and intertrigo (1%). No acne lesions were recorded. When the frequency of these skin disorders was compared according to the presence of overweight and grade of obesity, statistically significant differences were found for AN, skin tags, plantar hyperkeratosis, and striae. With the exception of striae, the frequency of the remaining skin disorders mentioned increased with the grade of obesity.

Frequency of Skin Disorders and Number of Skin Tags According to Overweight and the Grade of Obesitya

| Skin disorder, n (%) | AllN=109 | Overweightn=10 | Obesity | P | ||

| Grade I(n=20)n=15 | Grade II(n=25)n=25 | Grade III(n=54)n=44 | ||||

| Acanthosis nigricans | 106 (97) | 6 (60) | 19 (95) | 25 (100) | 54 (100) | .003 |

| Skin tags | 84 (77) | 5 (50) | 10 (50) | 21 (84) | 48 (88.9) | .001 |

| Hyperkeratosis | 42 (38.5) | 0 | 5 (25) | 7 (28) | 30 (55.6) | ND |

| Striae | 0 | 7 (35) | 4 (16) | 20 (37) | ND | |

| Hirsutism | 6 (5.6) | 0 | 0 | 4 (16) | 2 (3.7) | ND |

| Keratosis pilaris | 46 (42.2) | 4 (40) | 10 (50) | 8 (32) | 24 (44.4) | ND |

| Xerosis | 37 (33.9) | 5 (50) | 7 (35) | 7 (28) | 18 (33.3) | .668 |

| Venous insufficiency | 19 (17.4) | 0 | 3 (15) | 7 (28) | 9 (16.7) | ND |

| Hyperhidrosis | 10 (9.2) | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 8 (14.8) | ND |

| Onychocryptosis | 20 (18.3) | 0 | 4 (20) | 4 (16) | 12 (22.2) | ND |

| Dermatophytosis | 20 (18.3) | 0 | 3 (15) | 4 (16) | 13 (24.1) | ND |

| Other | 24 (22.0) | 3 (30) | 4 (20) | 4 (16) | 13 (24.1) | ND |

| Number of skin tags | 18 (7-18) | 4 (3-4) | 4.5 (4-6) | 11 (7-19) | 24 (14-35) | .000 |

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

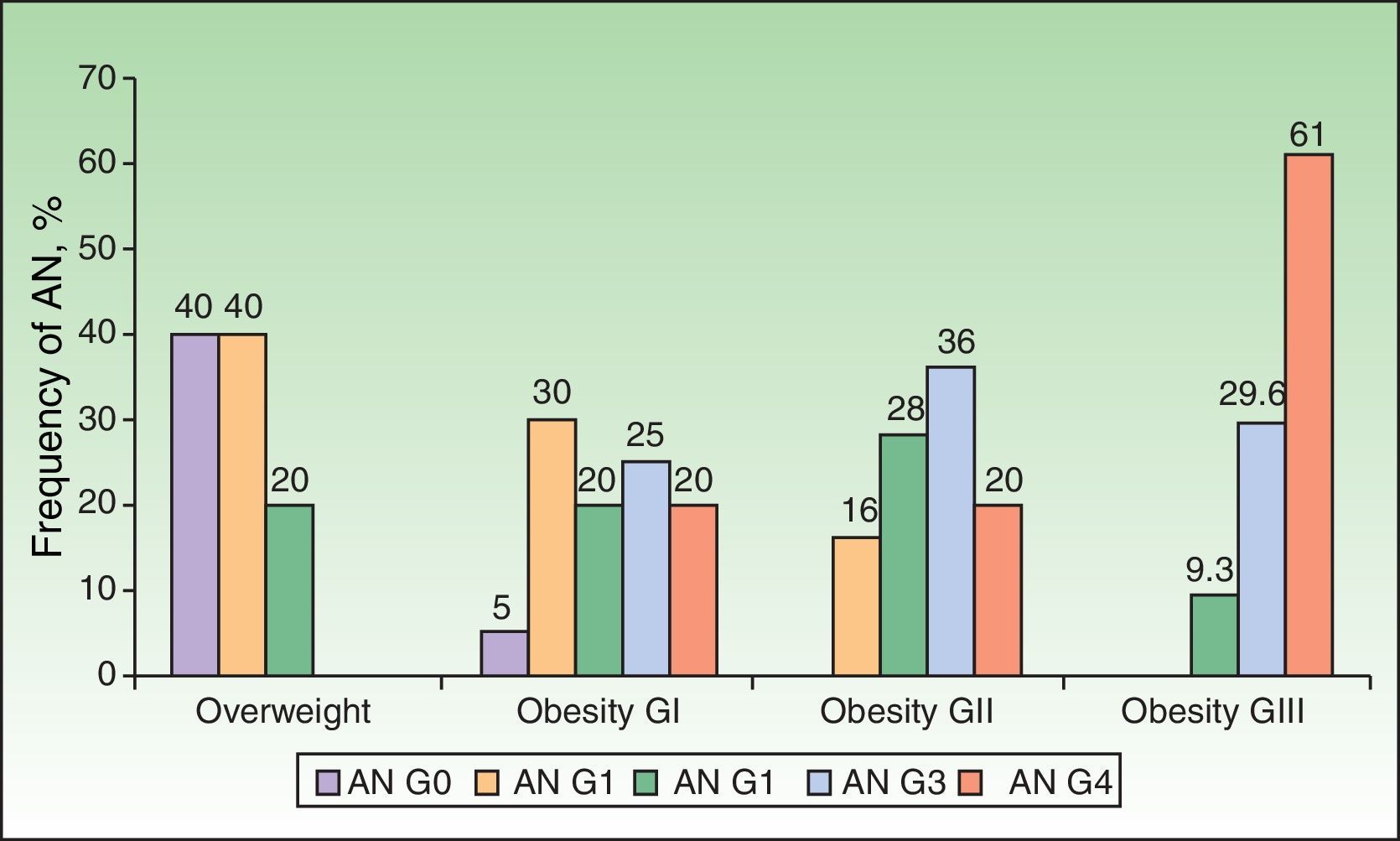

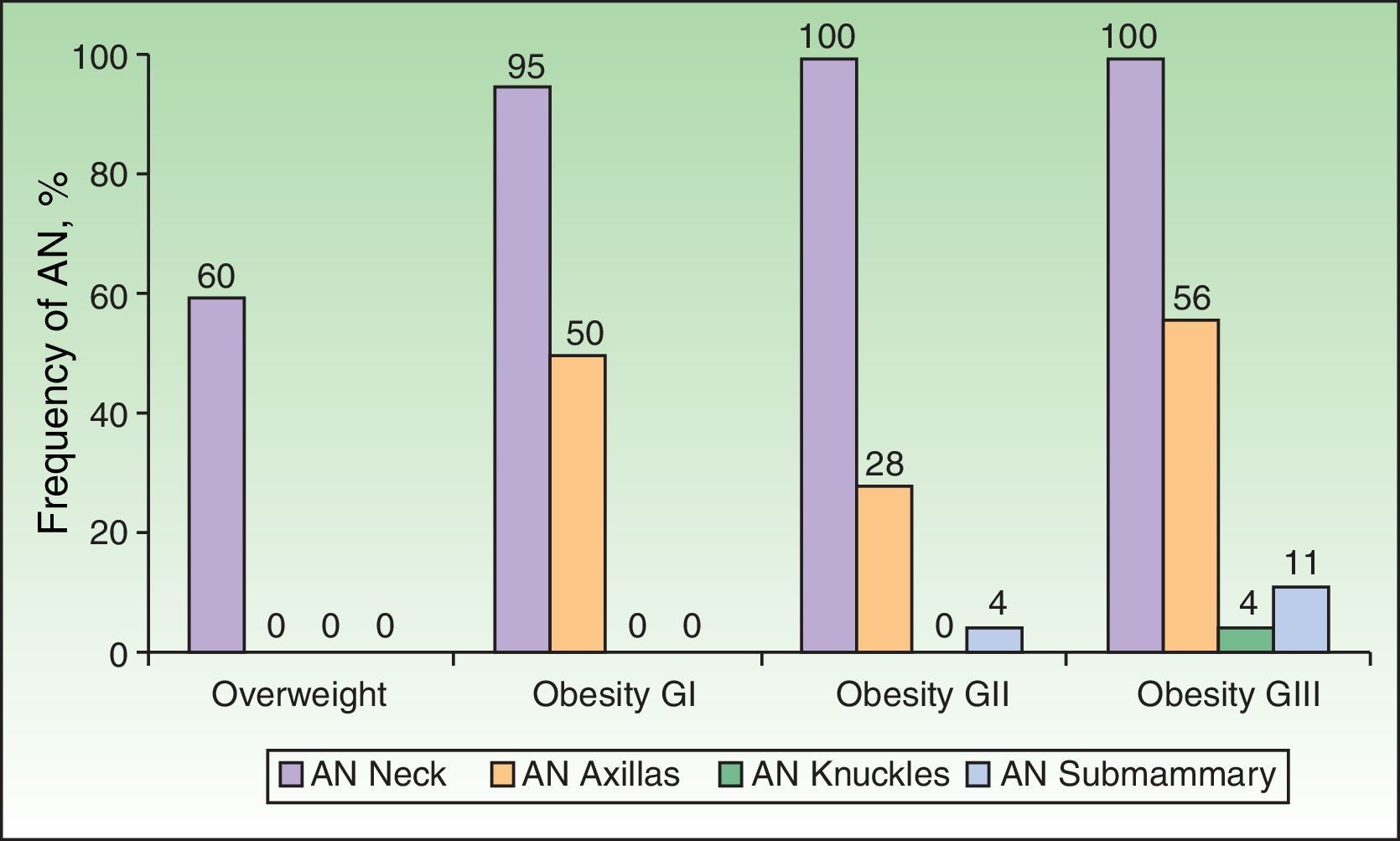

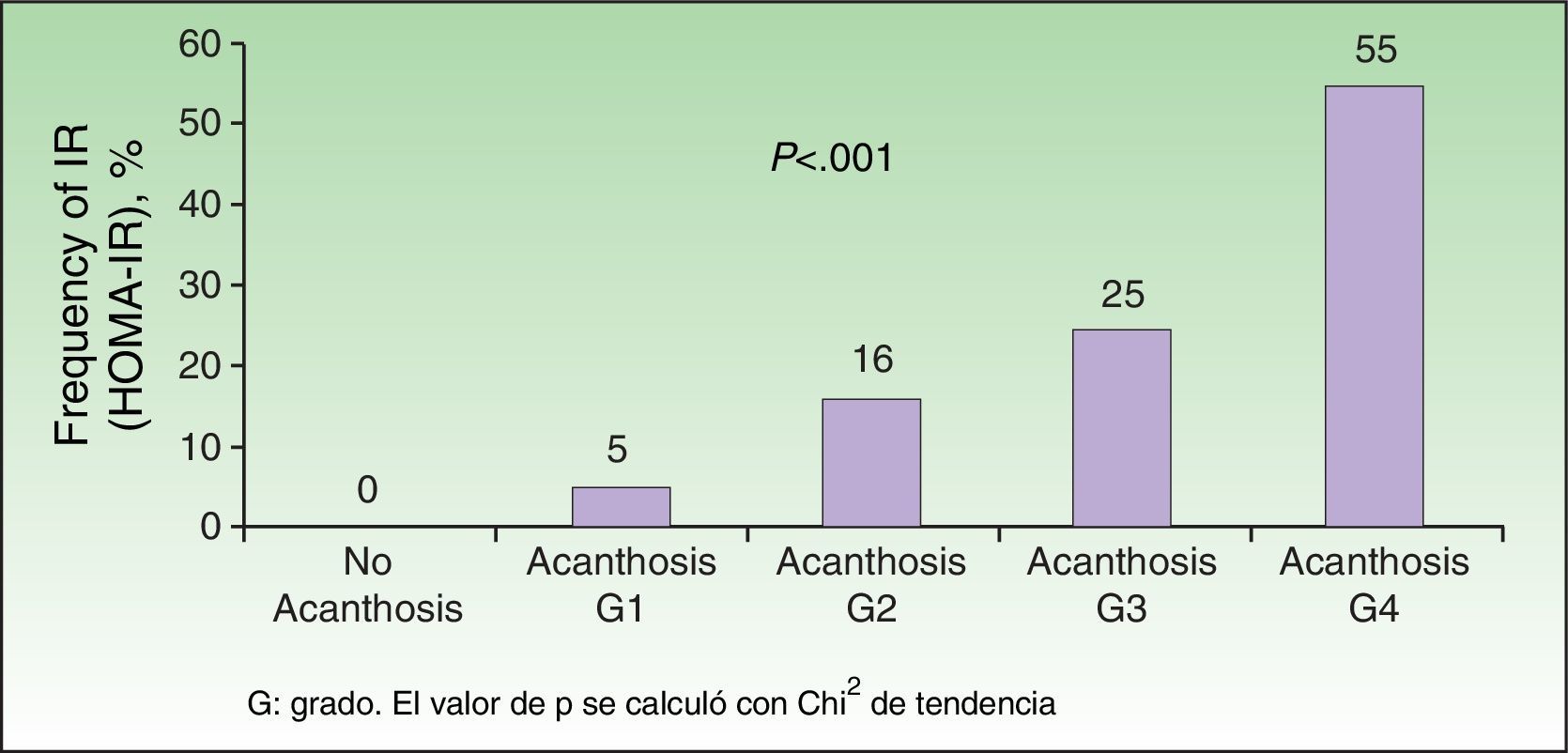

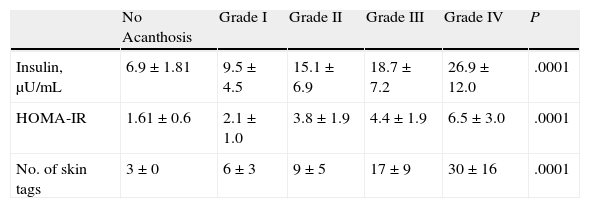

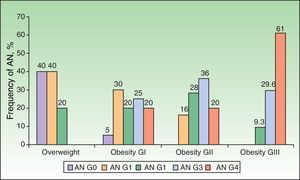

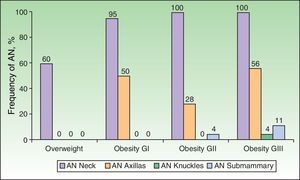

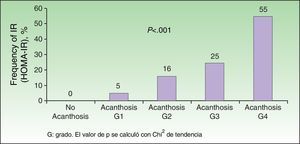

Analysis of the grade of AN on the neck revealed that 80% of overweight patients did not have AN (40%) or that AN was visible only at close inspection (40%), whereas 61% of the grade III group had grade 4 AN (Fig. 1). Acanthosis was present in all patients with grades II and III obesity. Similarly, more sites were affected in patients with grade III obesity (Fig. 2), and the percentage of persons with IR increased with the grade of AN on the neck (Fig. 3). The average values for insulin, HOMA-IR, and number of skin tags increased with the grade of AN on the neck (Table 4).

Median Values of Insulin and HOMA-IR and Number of Skin Tags According to the Grade of Acanthosis on the Necka

| No Acanthosis | Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | Grade IV | P | |

| Insulin, μU/mL | 6.9±1.81 | 9.5±4.5 | 15.1±6.9 | 18.7±7.2 | 26.9±12.0 | .0001 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.61±0.6 | 2.1±1.0 | 3.8±1.9 | 4.4±1.9 | 6.5±3.0 | .0001 |

| No. of skin tags | 3±0 | 6±3 | 9±5 | 17±9 | 30±16 | .0001 |

Abbreviation: HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance.

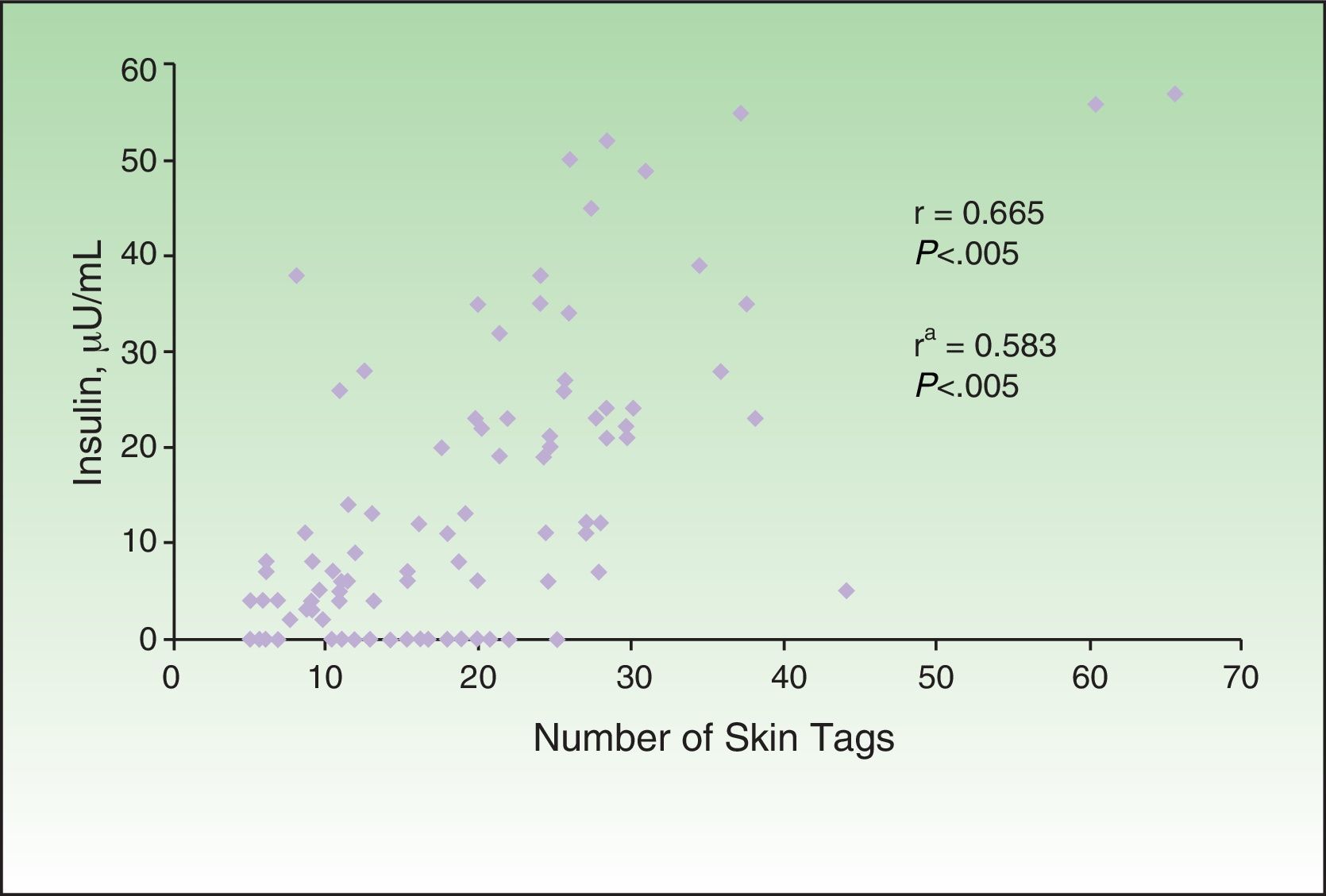

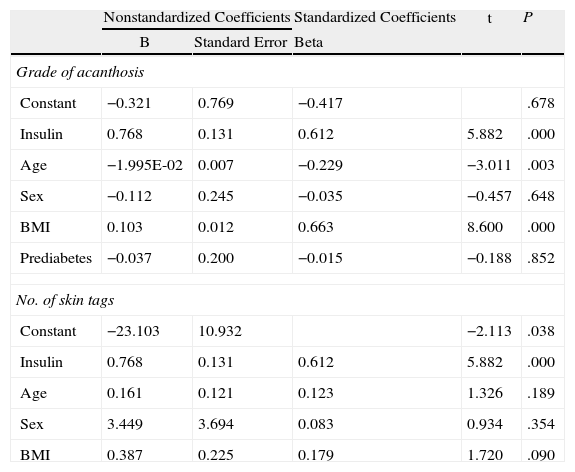

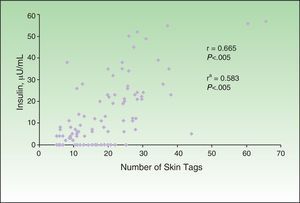

The correlation detected between the number of skin tags and insulin levels (r=0.665; P<.005) remained significant after adjustment for age, sex, and BMI (Fig. 4). Multiple and ordinal regression analysis confirmed the independence of the association between insulin levels and the grade of AN and the association between insulin levels and the number of skin tags, respectively (Table 5).

Ordinal Regression Analysis to Evaluate the Independence of the Association Between Insulin and the Grade of Acanthosis and the Number of Skin Tagsa

| Nonstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | P | ||

| B | Standard Error | Beta | |||

| Grade of acanthosis | |||||

| Constant | −0.321 | 0.769 | −0.417 | .678 | |

| Insulin | 0.768 | 0.131 | 0.612 | 5.882 | .000 |

| Age | −1.995E-02 | 0.007 | −0.229 | −3.011 | .003 |

| Sex | −0.112 | 0.245 | −0.035 | −0.457 | .648 |

| BMI | 0.103 | 0.012 | 0.663 | 8.600 | .000 |

| Prediabetes | −0.037 | 0.200 | −0.015 | −0.188 | .852 |

| No. of skin tags | |||||

| Constant | −23.103 | 10.932 | −2.113 | .038 | |

| Insulin | 0.768 | 0.131 | 0.612 | 5.882 | .000 |

| Age | 0.161 | 0.121 | 0.123 | 1.326 | .189 |

| Sex | 3.449 | 3.694 | 0.083 | 0.934 | .354 |

| BMI | 0.387 | 0.225 | 0.179 | 1.720 | .090 |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

AN was the most frequent skin disorder in the overweight and obese patients we studied (97%). This finding is consistent with data reported elsewhere.19–21 The presence of AN was directly proportional to the grade of obesity19,20 and was associated with high blood levels of insulin.21 AN is considered a skin marker of IR and hyperinsulinism. A high insulin concentration leads to direct activation of insulin receptors and activation in dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes via insulinlike growth factor 1, thus promoting their proliferation.22 AN is observed mainly in the axilla, groin, and neck, although it can also appear under the breasts and on the knuckles, elbows, and face.9 In the study group, AN was more disseminated and severity of AN on the neck increased with the grade of obesity. Although several authors confirm the association between AN and IR13,23,24 and AN and high levels of insulin,15 in Mexico, 2 studies have evaluated skin disorders in obese patients. The first was performed by García-Hidalgo et al.10 and included 156 obese patients (80% women), 48.7% of whom had diabetes and 29.5% AN. The second was performed by García-Solis et al.20 and included a large number of patients (3293 [age 15 to 40 years; 59.4% women], of whom 64.8% were overweight, 19% had grade I obesity, 9.6% grade II obesity, and 6% grade III obesity). The authors found that 1284 patients (38.9%) had obesity-associated skin disorders and that 14% had AN. The differences between the 2 Mexican populations cited and ours are clear, especially for age and grade of obesity. The selection bias arises because most of the patients we included attended the obesity clinic to undergo bariatric surgery; therefore, the grade of obesity was higher in our population. Also important is the observation that the patients were generally from a low or very low socioeconomic stratum, and this could be associated with having a skin phototype of IV or V, which can play a role in the manifestation of AN.21 Insulin levels were not determined in either of the 2 Mexican study populations.10,20 Hud et al.21 found AN in 74% of 34 obese individuals, most of whom were black.

Skin tags were detected in 77% of the patients included in our study, whereas in that of García-Hidalgo et al.10 they were detected in 44.2% of patients and in 50% of diabetic patients; in the study by García-Solis et al.,20 skin tags were only detected in 9.9% of patients. Skin tags are the second most common skin disorder in obese patients, and, as with AN, they are also directly associated with the grade of obesity19,20 and high insulin levels.15,19,25 Rasi et al.26 found that diabetes mellitus was more common in patients with skin tags and that having more than 30 skin tags considerably increased the risk of diabetes.26 Although one of the exclusion criteria was presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, a high frequency of prediabetes (38.5%) and IR (66.7%) was detected in the study population. Insulin concentrations increased with the grade of AN on the neck, as did the number of skin tags and the HOMA-IR index (Figs. 3 and 4). Guida et al.19 found that skin tags, plantar hyperkeratosis, AN, striae, intertrigo, hyperhidrosis, and keratosis pilaris were directly proportional to the grade of obesity. Except for keratosis pilaris, similar findings were observed in our study (Fig. 5).

Follicular keratosis or keratosis pilaris was found in 42.1% of patients, with no differences between the groups according to the grade of obesity. Although keratosis pilaris is more associated with atopy, it is also observed in obese patients, especially in those with a higher BMI,9,27 suggesting that high insulin levels and IR play an important role in its etiology.

Plantar hyperkeratosis was observed in 38.5% of cases, although in patients with grade III obesity, this figure increased to 55.6%, which was lower than that reported by some authors (80%)19 and higher than that found by others (34.6%).10 This skin disorder is more common in individuals aged over 60 years20 and should be considered a visible sign of severe obesity.8

Striae have been reported in 80% of patients with grade III obesity.19 However, in our study, they affected 37% of this group. The exact pathogenic mechanism of striae is unclear, although they could be considered scars resulting from damage to the collagen fibers of the dermal connective tissue followed by formation of new fibers with a lower capacity for support.9 The whitish striae associated with obesity were not correlated with insulin levels and were recorded in 28.4% of patients.

Xerosis was present in 34% of the study patients, although no association was established with grade of obesity; in the study by Brown et al.,8 67% of the patients were affected. Xerosis is associated with deficiency in humectants (collectively known as natural moisturizing factor), ceramides, and humectant modulated by aquaporin water channels.26–28

Venous insufficiency can worsen with obesity owing to increased abdominal pressure, which limits deep venous return in the legs.9 Moreover, delayed vasodilation after occlusion in obese patients29 could lead to venous insufficiency. The frequency of this disorder in our sample was 17.4%.

Intertrigo has also been associated with grade of obesity because of the increase in the number of skin folds and the prolonged and occlusive contact of skin with skin, friction, and accumulation of sweat, which is accompanied by increased pH, maceration, and, frequently, overpopulation of microorganisms on the skin surface.9 However, we only found 1 case, probably because of the cold climate of Mexico City and the period of the year when the study was performed (January to April).

Excessive production of androgens by the ovaries (theca cells) is associated with hyperinsulinemia, which is a consequence of IR. Hyperandrogenism leads to acne, hirsutism, and menstrual disorders. In our study population, polycystic ovary syndrome was recorded in 4 patients, hirsutism in 6, and pilar hyperkeratosis, which has also been associated with increased androgen levels,30 in 42.2%. However, none of the patients had acne lesions.

When the groups were evaluated according to overweight and grade of obesity, the statistically significant skin disorders were AN, skin tags, plantar hyperkeratosis, and striae. The grade of AN on the neck was significantly associated with blood insulin levels and IR (defined as a HOMA-IR index>3). Similar findings were recorded for anatomical site: the higher the grade of obesity, the more sites were affected (neck, axillas, intermammary region, and knuckles in patients with grade III obesity). Similarly, a statistically significant association was observed between the number of skin tags and the grade of obesity and insulin levels. The association between insulin levels and grade of AN varied with the inclusion of age in the model (the lower the age, the higher the grade) and BMI (the higher the BMI, the higher the grade). These observations agree with reports from the pediatric population, where it was shown that BMI accounts for 41% of the variance in insulin sensitivity (measured using the clamp technique) and AN accounts for only 4% of the variance.31 On the other hand, the independent association between serum insulin levels and the number of skin tags did not change with the inclusion of age, sex, and BMI in the model.

Although obesity is recognized as a public health problem, its impact on the skin has received little attention. Obesity is responsible for various changes in the physiology of the skin, which can lead to a wide range of skin diseases or worsening of existing skin disorders. With the increase in the number of obese patients, dermatologists must adapt and improve current local and systemic therapy and work with primary care physicians to reduce the deleterious effects of obesity on the skin.

ConclusionsOurs is the first prospective study in Mexico and Latin America to report the association between insulin levels and grade of AN on the neck and number of skin tags in a selected population of overweight and obese patients. Although other studies have shown that AN improves significantly with increased sensitivity to insulin and reduced weight, skin tags have to be treated by a dermatologist.

The presence of AN on the neck and skin tags in an overweight or obese person are easily identifiable clinical signs that could point to hyperinsulinemia secondary to IR. General practitioners, internists, and pediatricians should consider AN as a warning sign urging them to make a deliberate search for abnormalities associated with hyperinsulinemia, such as increased blood sugar, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed their hospital's protocol on the publication of data concerning patients and that all patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Plascencia Gómez A, Vega Memije ME, Torres Tamayo M, Rodríguez Carreón AA. Dermatosis en pacientes con sobrepeso y obesidad y su relación con la insulina. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:178–185.