Beta-blockers (BB) have become the treatment of choice for infantile hemangiomas (IH).1 Among this class of drugs, propranolol has taken the lead, consolidating its efficacy and safety profile,2 and becoming the only beta-blocker approved for this indication.3 However, some patients exhibit limited therapeutic response or experience related adverse events, leading us to consider other beta-blockers as an alternative to propranolol.4

We reviewed patients with IH treated with oral nadolol at the Dermatology Unit of Hospital Universitario Costa del Sol, Málaga, Spain from 2010 through 2022. Nadolol was administered in an oral solution formulation prepared at the hospital pharmacy at a concentration of 10mg/mL. The initial dose was 1mg/kg/day, divided into 2 doses every 12hours, with an increased 1mg/kg/day every 10 days (with a maximum dose of 3mg/kg/day) depending on the patient's response and tolerability to the drug.

Response to treatment was assessed using a validated visual analog scale5 that measures thickness and size in millimeters (a 5mm reduction is equivalent to a 10% change on the scale) and skin coloration. Good (complete involution or remissions >80%), partial (remissions from 50% to 80%), and incomplete responses (remissions<50%) can be identified here.

A total of 7 patients received nadolol, 6 of whom were women. The patients’ demographic and hemangioma-related clinical characteristics are shown in table 1. In all cases, nadolol was prescribed after previous use of propranolol.

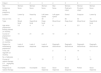

Demographic characteristics of the patients and therapy timeline.

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Woman | Woman | Woman | Man | Woman | Woman | Woman |

| Incidences during pregnancy | None | None | None | None | Post-term infant | Pre-term infant | None |

| Location | Lower lip | Nasal tip | Left lower eyelid | Left upper eyelid | Dorsal | Scapular | Lower lip |

| Size (in mm) | 10 | 10 | 30 | 7 | 80 | 50 | 15 |

| Type | Mixed focal | Superficial focal | Deep focal | Mixed focal | Deep focal | Mixed focal | Superficial focal |

| Age when propranolol therapy started (in months) | 5.5 | 4 | 1.5 | 6 | 4 | 2.5 | 3 |

| Course of propranolol therapy 3mg/kg/day (in months) | 15 | 21 | 24 | 10 | 27 | 14 | 8 |

| Reason for withdrawing propranolol | Lack of response | Lack of response | Lack of response | Regrowth, discontinue | Regrowth, discontinue | Regrowth, discontinue | Regrowth, discontinue |

| Time until regrowth (in months) | 2 | 4 | 14 | 1 | |||

| No. of attempts | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Course of nadolol therapy 2.5mg/kg/day (months) | 7 | 5 | 19 | 7 | 8 | 15 | 16 |

| Response to nadolol therapy | Incomplete | Incomplete | Good response | Good response | Good response | Partial | Good response |

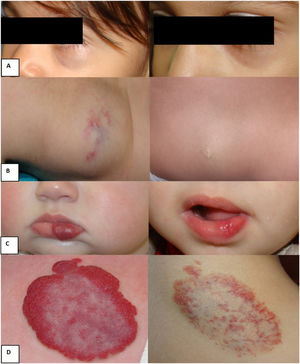

The median age when treatment with propranolol started was 4 months (IQR, 2.5-5.5), with all patients reaching the maximum dose of 3mg/kg/day. The median duration of treatment was 15 months (IQR, 10-24). The reason for withdrawing propranolol was a lack of response in 3 patients and lesion regrowth after drug discontinuation on several occasions in the remaining 4. None of our patients discontinued propranolol due to adverse events such as sleep disturbances or hypoglycemia. The median age when treatment with nadolol started was 21 months (IQR, 16-36) at a dose of 2.5mg/kg/day (IQR, 2-3), and a median course of 8 months (IQR, 7-16). Regarding effectiveness, 4 patients had good responses; 1 patient had a partial response (fig. 1); and 2 patients, incomplete responses. The rate of response was 5 out of 7 patients. No patient had to discontinue nadolol therapy for any drug-related adverse events. The timeline of treatments, courses, and patient responses are shown in table 1.

Examples of responses to nadolol treatment: A) Deep focal hemangioma on the left lower eyelid; age when nadolol treatment started: 24 months; age when nadolol treatment was withdrawn: 43 months. Good response. B) Dorsal focal deep hemangioma; age when nadolol treatment started: 40 months; age when nadolol treatment was withdrawn: 48 months. Good response. C) Superficial focal hemangioma on the lower lip; age when nadolol treatment started: 11 months; age when nadolol treatment was withdrawn: 27 months. Good response. D) Mixed focal scapular hemangioma; age when nadolol treatment started: 30 months, age when nadolol treatment was withdrawn: 45 months. Partial response.

In our series of 7 cases, the main reason for switching from propranolol to nadolol was the regrowth of the hemangioma after discontinuation after several attempts, a well-documented phenomenon in the medical literature reported in nearly 25% of the cases.6 Risk factors for regrowth include female gender, head and neck location, segmental character, deep components, and a <9-month course of beta-blockers.4 The lack of initial response to propranolol was reported in 3 patients, a number similar to the one reported. The cause of this inefficiency is still unknown. However, treatment should go on for >6 months to increase the rate of success.6 In our series, the mean course of treatment exceeded this recommendation by far (up to 15 months). None of the patients switched to nadolol due to propranolol-related adverse events.

Nadolol is a water-soluble beta-blocker with a half-life of 12 to 24hours. These pharmacokinetic properties theoretically give it certain advantages over propranolol when administered to young patients. Since nanodol does not penetrate the blood-brain barrier, it has with fewer adverse events on the central nervous system, and thus fewer sleep disturbances compared to propranolol. However, same as it happens with propranolol, it is a non-cardioselective BB, meaning that it can cause the same adverse events due to its beta 2 and beta 3 adrenergic activity, such as hypoglycemia and bronchospasm.7 Since the main pathway for drug excretion is the GI tract (up to 70%), the infant's bowel movements needs to be monitored, especially after a case reported in the medical literature of a patient who died from nadolol intoxication who was suffering from constipation.8 On the other hand, its half-life is twice that of propranolol, which is associated with more stable drug levels in blood.9 This is the main hypothesis that may explain why nadolol may have faster onsets of action and be more effective than propranolol. A recent double, prospective, non-inferiority clinical trial comparing the efficacy and safety profile of nadolol vs propranolol10 demonstrated that the former was 59% faster than the latter in achieving a 75% reduction in size, and 105% faster in achieving hemangioma disappearance, all without more adverse events being reported.

In conclusion, nadolol has proven to be an effective and safe drug with a favorable pharmacokinetic profile, and non-inferior and faster rates of response compared to propranolol. This has turned it into the first-line therapy for the management of high-risk subtypes of hemangiomas with associated factors for recurrence.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.