A 59-year-old female patient from Ecuador with phototype IV and a history of early ovarian insufficiency, glaucoma, and allergic rhinitis consulted for progressive hyperpigmentation of the face that had started 10 years earlier. She reported that her father had been diagnosed with ashy dermatosis affecting the skinfolds.

Physical ExaminationA dermatological examination revealed multiple asymptomatic hyperpigmented reticular macules on the eyelids, malar region, nasal bridge, chin, and neckline (Fig. 1). In addition, the patient presented alopecia in the frontotemporal region with hairline recession, isolated terminal hairs (compatible with lonely hair sign), complete alopecia of the eyebrows, and partial alopecia of the eyelashes, onset of which coincided with that of the facial hyperpigmentation (Fig. 2). Neither nail nor mucosal involvement were observed.

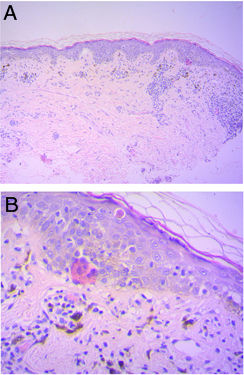

HistopathologyHistopathological study of the hyperpigmented skin of the chin, carried out 5 years earlier, showed an irregular epidermis with basket-weave hyperkeratosis and areas of atrophy, necrotic keratinocytes, vacuolization of the basal layer, and the presence in the underlying dermis of a band-like perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and melanophages. These findings were compatible with vacuolar interface dermatitis (Fig. 3).

Additional TestsOver the years, various additional tests were requested (porphyrins, blood lead, basal cortisol), the results of which ruled out differential diagnoses such as cutaneous porphyria, lead poisoning, and Addison syndrome.

What is the Diagnosis?

Based on the clinical and histopathological findings and the literature review, a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) associated with frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) was established. The following entities were considered in the differential diagnosis: exogenous ochronosis, ashy dermatosis, Riehl melanosis, and melasma.

Clinical Course and TreatmentPrior to diagnosis, the patient had received intermittent treatment with 4% hydroquinone and mometasone cream in hyperpigmented areas, and minoxidil and finasteride lotion in areas of alopecia, with no improvement.

Based on the new suspected diagnosis, the patient began daily treatment with 0.03% tacrolimus cream and Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser, in addition to photoprotection.

CommentsLPP is a rare variety of lichen planus, first described in India. It occurs between the third and fourth decades of life, mainly in women with high phototypes. It manifests with the insidious appearance of small hyperpigmented macules with a slate gray or brown coloration. These macules can coalesce to form larger lesions with a reticular, perifollicular, or diffuse pattern. The lesions are asymptomatic or mildly pruritic, and are located bilaterally in sun-exposed areas and skin folds.

Histology shows basket-weave hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum, epidermal atrophy, keratinocyte apoptosis, vacuolization of the basement membrane, perivascular or band-like inflammatory infiltrate, and dermal melanophages,1 all of which were observed in our patient's biopsy. The etiology is unknown. The described pattern indicates a lichenoid-like immunological reaction to an as-yet-unknown agent or stimulus. Possible triggers include mustard oil, amla oil, and henna dye, all of which are hair care and beauty products used in Asian populations.2

The association between LPP and FFA was first reported in 2013 by Dlova,3 who described a series of cases in which both entities coincided in South African perimenopausal patients. Moreno-Arrones et al. reported a significant association between FFA and other autoimmune diseases such as LPP and hypothyroidism.4 Several other authors have since described this association, in which LPP usually precedes FFA by months or even years.

The therapeutic options described to date are limited and unsatisfactory. Mutairi and Khalawany5 published a study in which 13 patients diagnosed with LPP were prescribed 0.03% tacrolimus for a period of 16 weeks. Half of the patients showed an excellent response, starting at week 8. Q-switched Nd:YAG or picosecond laser may be indicated for treatment of residual pigmentary incontinence.6

Some authors consider FFA a clinical variant of lichen planus pilaris, the follicular form of lichen planus.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Dr. Luis D. Mazzuoccolo, head of the Dermatology Service of the Italian Hospital of Buenos Aires, for his assistance in reviewing the manuscript.