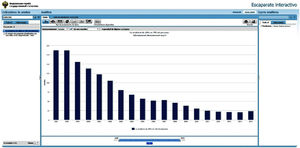

The rapid social, political, and economic transformations in Russia after the break-up of the Soviet Union led to a change in the traditional approach to sexual habits and values among the population. This was accompanied by a deterioration in the public health service, including prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections, which led to a dramatic increase in the frequency of syphilis.1 This increase was so pronounced that in 1996, the rate (254.2 cases per 100 000 inhabitants) was 48 times greater than in 1989. The disease mainly affected young women, and the number of reported cases of congenital syphilis multiplied 26-fold during the period 1991–1999 (from 8.04 per 100 000 to 209 per 100 000).2,3 Rates have fallen since then,4,5 although the incidence has remained high (56.7 per 100 000 in 2005; 30.5 per 100 000 in 2010; 23.6 per 100 000 in 2015) (Fig. 1).

Russia is a key country for international adoption in Spain.6 In the present investigation, we analyzed a cohort of children adopted from Russia to determine the prevalence of active maternal syphilis during pregnancy, congenital syphilis in children, and the results of serology testing for syphilis after arrival in Spain.

A total of 450 children adopted from Russia were studied after their arrival in Spain during the period 2000–2017 at the Center for Pediatrics and International Adoption (Centro de Pediatría y Adopción Internacional) in Zaragoza. The mean (SD) age was 31.3 (18.3) months, and 62.2% were boys. Similarly, we evaluated the preadoption medical reports from Russia. It is important to remember that the absence of a history of syphilis in the preadoption medical report does not rule the disease out.6 In line with the state consensus document on the basic medical evaluation of children adopted from overseas, all of the children underwent serology testing for syphilis (rapid plasma reagin or venereal disease research laboratory test). If the reagin tests are positive, then a treponema-specific test (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption) is necessary for confirmation. This test is also performed in all children aged under 1 year when there is high clinical suspicion or confirmation that the biological mother had syphilis.7

Evaluation of preadoption medical reports revealed that at least 16% (n = 72) of the biological mothers had active syphilis during pregnancy and that at least 32% (n = 23) of children of a mother with active syphilis had congenital syphilis. The sensorineural and physical examination the children underwent after arrival did not reveal lesions or stigmata that are characteristic of the disease in any cases, and the syphilis serology test result was negative in all cases. A treponema-specific test performed in 5 children aged <1 year whose mothers had confirmed syphilis yielded a negative result.

Epidemiological and clinical studies performed by the Congenital Syphilis Investigation Team (CSIT) of the Russian Ministry of Health reported that in Russian pregnant women with active syphilis, between 25% and 64% had a newborn with congenital syphilis. They also found that in the case of pregnant women who did not undergo medical check-ups for their pregnancy or who had their first check-up late (> 28 weeks) and did not receive treatment or received insufficient treatment or did not complete treatment, the risk of congenital syphilis in the newborn was as high as 86%.8,9 In Russia, appropriate treatment of primary, secondary, and all forms of latent syphilis during pregnancy comprises administration of long-acting penicillin G benzathine, as well as daily administration of short-acting penicillin G procaine. Either of these 2 therapy regimens must be completed at least 30 days before delivery. The regulations stipulate that only dermatologists and venereologists are authorized to treat pregnant women infected by syphilis, although, as a result of the recommendations of the CSIT, national policy is beginning to be reformed.8 For a child to be diagnosed with congenital syphilis in Russia, he/she must have clinical symptoms or persistent serological abnormalities. According to the CSIT, these requirements may lead the frequency of the disease to be underestimated, since they do not consider asymptomatic children, i.e., the majority, to be probable cases. Most of these children were born to mothers with untreated or inadequately treated syphilis. In any case, health care policy stipulates that the children must receive preventive treatment with penicillin.8,9

The prevalence of early and late congenital syphilis in children adopted from Russia is lower than 0.05%,10 thus indicating that they are well diagnosed, treated, and followed up in their country of origin. In any case, despite this low prevalence, we consider it important to continue screening for syphilis after the child’s arrival in the country of adoption.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Oliván-Gonzalvo G. Prevalencia de sífilis en niños adoptados de Rusia. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:623–624.