Leprosy reactions, which are abrupt changes in the clinical condition of patients with immunologically unstable forms of the disease, can mask the cardinal signs of leprosy, delaying both diagnosis and treatment. The main complications that arise from delayed diagnosis reflect the characteristic features of the disease, involving impaired nerve function and both local (ulcers, pyogenic infection, osteomyelitis) and systemic compromise. Thorough clinical examination, sensory testing, and, where necessary, histopathology and microbiology, are essential when leprosy is suspected. Rapid initiation of anti-inflammatory treatment reduces the risk of functional impairment, the main concern in leprosy. We describe type 1 and type 2 leprosy reactions in 2 patients who had not yet been diagnosed with the disease.

Las leprorreacciones suponen cambios clínicos de inicio súbito en los pacientes que presentan formas inmunológicamente inestables de la enfermedad de Hansen. Estos cuadros pueden enmascarar los signos cardinales de la misma y demorar así su diagnóstico y tratamiento. Las principales complicaciones derivadas de este retraso son las relacionadas con el compromiso neural, local (ulceraciones, piodermitis, osteomielitis…) y/o sistémico característico de estos cuadros. Ante su sospecha debe realizarse un minucioso examen clínico, exploración de la sensibilidad y, cuando se precise, estudio histopatológico y microbiológico. La instauración inmediata de tratamiento antiinflamatorio disminuye el riesgo de secuelas funcionales, principal causa de morbilidad en la lepra. A continuación, se presentan dos casos de leprorreacciones de tipo I y II en pacientes no diagnosticados hasta ese momento de enfermedad de Hansen.

Hansen disease, or leprosy, is uncommon in Spain. It is no longer considered a public health problem in our country1,2 and most new cases are imported from leprosy-endemic areas in Southeast Asia, South America, and Africa.3 The virtual absence of autochthonous cases and the added difficulty of evaluating dermatological conditions in patients from other racial groups complicate the early diagnosis of leprosy.

Leprosy is characterized by a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations that affect the skin, the mucosas, the eyes, the organs, and/or the nerves. On occasions, its cardinal signs or symptoms may be masked by sudden clinical changes known as leprosy reactions,4 which are triggered by changes in immune response.5,6 Multiple factors are involved in the development of leprosy reactions, but commencement of specific leprosy treatment is a factor in a considerable number of cases.

We describe 2 cases of type 1 and type 2 leprosy reactions in patients with previously undiagnosed leprosy that illustrate the diagnostic challenges in such cases.

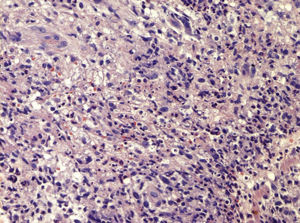

Case DescriptionsThe first patient, a 25-year-old woman from Brazil who had been living in Spain for 6 months, visited the emergency department with high fever (up to 39°C), general malaise, watery rhinorrhea, and painful, erythematous nodules located predominantly on the limbs (Fig. 1). The manifestations had started the previous week, but the patient had experienced similar lesions—which cleared spontaneously—on several occasions in the previous 3 months. Blood tests revealed a normocytic, normochromic anemia, leukocytosis with neutrophilia, mild elevation of the tranaminases, and considerably increased serum levels of immunoglobulin G. The ear, nose, and throat examination confirmed mucosal edema in the paranasal sinuses. The skin examination revealed multiple, asymptomatic brownish papules symmetrically distributed on the legs and the arches of the soles that were clinically diagnosed as lepromas. There were also purple nonulcerated papules on the distal third of the toes (Fig. 2). The path of the right common peroneal nerve was thickened and electromyography demonstrated a severe sensory-motor neuropathy. Biopsy of a nodule showed a diffuse inflammatory infiltrate in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue composed of lymphocytes, neutrophils and histiocytes with vacuolated cytoplasm (Fig. 3). The neutrophils exhibited marked tropism for the walls of the small dermal vessels but there was no evidence of fibrinoid necrosis. Ziehl-Neelsen staining showed acid-alcohol-fast bacilli (AAFB) within the histiocytes. A slit-skin smear taken from the earlobe, elbow, and a brownish papule on the leg showed 10 AAFB in one 100× microscope field (bacterial index, 3+). The diagnosis was erythema nodosum leprosum in a patient with subpolar lepromatous leprosy. Multiple drug therapy (MDT) was initiated following the regimen recommended by the World Health Organization for patients with multibacillary leprosy (rifampicin, clofazimine, and dapsone) in combination with oral corticosteroids (prednisone, 1mg/kg/d). The nodules, fever, and general malaise all resolved. However, when the corticosteroid dose was reduced to 0.5mg/kg/d, the patient experienced a new episode of nodules and fever that required treatment with thalidomide (150mg/d). The response was complete.

The second patient was a 38-year-old man, born in the Philippine Islands and resident in Spain for 4 months, who visited the emergency department following the sudden worsening of annular skin lesions that had developed initially on the face and been treated in the patient's country of origin a year earlier. There was no fever or other systemic symptoms. The patient was questioned further but could not remember what treatment he had received or for how long. Physical examination showed erythematous, edematous plaques that were neither painful nor hot and were located on the lesions initially described by the patient (Fig. 4). There was also a striking alteration of the nasal pyramid due to a road traffic accident. The neurological examination revealed moderate hypoesthesia in the area of a scaly plaque on the right leg. Two biopsies were taken: one from an erythematous, edematous plaque on the face and the other from the scaly plaque on the right leg. Multiple noncaseating granulomas surrounded by a crown of lymphocytes and located mainly around the nerves and the skin appendages were visible in both lesions, together with edema of the superficial and deep dermis. Skin-smear examination of a facial plaque showed a low bacillary load (2+) of AAFB. The diagnosis was a type 1 reaction in a patient with borderline leprosy. We initiated treatment with corticosteroids (prednisone, 0.5mg/kg/d), which led to a gradual improvement, plus MDT (rifampicin, clofazimine, and dapsone) for 12 months in view of the little information available on previous treatments.

DiscussionLeprosy reactions are sudden changes in the clinical condition of patients diagnosed with leprosy.4 They typically occur in patients with immunologically unstable forms of leprosy, but no clinical predictors have been identified to date. These clinical conditions, which are defined according to the Ridley-Jopling classification,7 fall within the spectrum of clinical, microbiologic, histologic, and immunologic manifestations that occur between the 2 extremes, or poles, of leprosy: at one end, tuberculoid or paucibacillary leprosy and at the other, lepromatous or multibacillary leprosy (Table 1).

Characteristics of Type 1 and 2 Leprosy15–17 Reactions.

| Type 1 Reactions | Type 2 Reactions | |

| Immune response | Type 1 helper cells | Type 2 helper cells |

| Pathogenesis | Type IV (delayed cell-mediated) hypersensitivity reaction | Type III hypersensitivity reaction (immune complex formation and deposition) |

| Clinical subtypes | TTS, BT, BB | BL, LLS |

| Host | Previous treatment (except in downgrading reactions) | Previous treatment or not |

| Types | Reversal reactionDowngrading reaction | Erythema nodosum leprosumLucio phenomenonErythema multiforme-like reaction |

| Cutaneous manifestations | Edema of previous lesionsIncrease in distal scalingNerve involvement | NodulesNecrotic areasPolymorphous erythematous plaquesNerve involvement |

| Histopathology (changes with respect to conventional histologic findings) | Tuberculoid granulomasDermal edema | Neutrophilic infiltrate in the mid and deep dermis and subcutaneous cellular tissueLeukocytoclastic vasculitis of the small and medium vessels |

| Treatment | RestNSAIDsSystemic corticosteroids | RestAcetylsalicylic acid, pentoxifyllineSystemic corticosteroidsClofazimineThalidomide |

Abbreviations: BB, mid-borderline leprosy; BL, borderline lepromatous leprosy; LLs, subpolar lepromatous leprosy; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TTs, subpolar tuberculoid leprosy.

The factors involved in the development of these states disrupt the balance between the mycobacteria and the host's immune system. Examples of triggers that alter the immune state are adrenal gland insufficiency, stress, intercurrent infections, pregnancy, and, in particular, specific leprosy treatment.8

Classically, there are 2 types of type 1 leprosy reactions: an upgrading, or reversal, reaction and a downgrading reaction.9 Downgrading reactions are assumed to represent a shift towards the lepromatous (multibacillary) pole of the disease and are correlated with a decrease in cellular immune response. Reversal reactions, by contrast, are seen in patients who have received treatment and experience an increase in immune response. Type 1 reversal reactions are considered to be a delayed hypersensitivity reaction (or type IV reaction according to the Gell and Coombs classification), involving augmented type 1 helper T-cell response.9,10 Clinically, pre-existing lesions become inflamed and there is considerable exacerbation of neurological manifestations (polyneuritis with marked inflammation of the nerves). Patients may sometimes develop new lesions and general malaise, usually due to the sudden neurological deterioration. Treatment includes rest and systemic corticosteroids.

Type 2 leprosy reactions are essentially due to a type III hypersensitivity reaction, mediated by circulating immune complexes formed by antibodies binding to antigens. These complexes cannot be cleared by the kidneys or phagocytized by macrophages and therefore deposit on the vessel walls.11 The release of inflammatory cytokines and the subsequent recruitment of neutrophils contribute to the development of characteristic clinical manifestations that vary according to the organ involved. When the skin is affected patients develop painful inflammatory nodules (a condition known as erythema nodosum leprosum as it is not an inflammatory process occurring within the septa of the subcutaneous tissue), necrotic areas (Lucio phenomenon), or plaques resembling erythema multiforme. Patients may also develop neuritis, with palpable, painful enlargement of the affected nerves.12 Treatment includes rest, acetylsalicylic acid, pentoxifylline, systemic corticosteroids, and clofazimine. However, thalidomide (100-300mg/d) remains the treatment of choice in recurrent cases because it is well tolerated and maintains prolonged remission.13,14 Women of childbearing age receiving this drug must be warned to use effective contraception.

Early diagnosis of leprosy reactions is very important. While these reactions are uncommon in our setting, a late diagnosis can lead to irreversible nerve damage and severe functional impairment.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of humans and animalsThe authors declare that no tests were carried out in humans or animals for the purpose of this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no private patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pulido-Pérez A, Mendoza-Cembranos MD, Avilés-Izquierdo JA, Suárez-Fernández R. Eritema nudoso leproso y reacción de reversión en 2 casos de lepra importada. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:915–919.