Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a malignant neuroendocrine tumor. Metastasis or lymph node spread is often detected at diagnosis. We performed a descriptive, retrospective study of patients diagnosed with MMC at Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón in the Community of Madrid, Spain between January 1998 and December 2018. Eleven patients (7 men [63%] and 4 women [36%]; mean age, 77.6 years) were diagnosed with MCC during this 21-year period; 45% of patients had stage IIIB disease (pTNM) at diagnosis. All patients but one underwent local surgery, and lymphovascular invasion was detected in 7 cases. Eight patients received adjuvant therapy after surgery (radiation therapy in 5 cases and chemotherapy in 3). Six patients (54%) died of MCC (mean survival, 14.5 months). MCC is an uncommon malignant tumor with an annual incidence of around 0.18–0.41 cases per 100000 inhabitants; this is similar to the rate of 0.29–0.32 cases per 100000 inhabitants a year detected in our series. Results with avelumab, a drug recently approved for the treatment of metastatic MCC; have been promising.

El carcinoma de células de Merkel (CCM) es una neoplasia neuroendocrina maligna. Con frecuencia existe diseminación ganglionar o metástasis al diagnóstico. Realizamos un estudio descriptivo retrospectivo de los pacientes con CMM del Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón entre enero/1998 y diciembre/2018. En 21 años diagnosticamos 11 pacientes con CCM: 7 varones (63%) y 4 mujeres (36%), con una edad media de 77,6 años. El 45% de los pacientes presentaron un estadio IIIB (pTNM) al diagnóstico. Todos los pacientes menos uno, fueron subsidiarios de cirugía local, identificándose en 7 casos invasión linfovascular. Tras la cirugía, 5 pacientes recibieron radioterapia adyuvante y 3 quimioterapia adyuvante. El 54% fallecieron por el tumor (tiempo medio supervivencia: 14,5 meses). El CCM es una neoplasia maligna infrecuente cuya incidencia se sitúa en 0,18-0,41 casos/100.000 habitantes/año, similar a los 0,29-0,32 casos/100.000 habitantes/año registrados en nuestra serie. Recientemente ha sido aprobado avelumab para casos metastásicos con esperanzas prometedoras.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an uncommon malignant neuroendocrine neoplasm that often first manifests in advanced stages. It is found on sun-exposed areas of skin in elderly patients, and spread to lymph nodes or metastasis is often detected at diagnosis. The incidence of MCC has been increasing in recent decades owing to aging of the population, increased life expectancy, and improved diagnostic techniques (immunohistochemistry).1

Data on the incidence of MCC in Spain are lacking. Therefore, the primary objective of our study was to perform a descriptive analysis of demographic, clinical, and histopathologic data and thus report the incidence of MCC in the present series. Our secondary objective was to report the median survival of the patients studied.

Material and MethodsWe performed a retrospective descriptive study of all patients diagnosed with MCC at Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón (HUFA), Alcorcón, Spain between January 1998 and December 2018. Until 2011, the catchment population of our center was 273703 inhabitants, which has fallen to 103000 since 2012. Based on the electronic clinical history and the database of our Histopathology Department, we recorded all demographic variables (sex, age at diagnosis), clinical data (type of lesion, maximum tumor size, ulceration), histopathology data (tumor cellularity, immunohistochemistry techniques, cell proliferation index), treatments (type of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy), course, and survival. The data obtained were entered into an anonymized database and analyzed using SPSS Statistics, Version 20.0 (IBM Corp.). Qualitative variables were expressed as percentages, whereas quantitative variables were expressed as median (range). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research With Medications of HUFA.

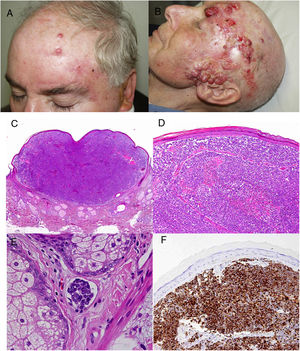

ResultsOver a period of 21 years (1998–2018), we diagnosed 11 patients with MCC (7 men [63%] and 4 women [36%]; mean age at diagnosis, 77.6 years; median age, 81 years [60–92]) (Table 1). The tumor was located on the head and neck in 5 cases (45%), on the limbs in 5 cases (45%), and on the trunk in only 1 case (10%). All patients had a Fitzpatrick skin phototype of II–III, and none were immunosuppressed. In clinical terms, the lesions were considerably polymorphous, presenting mainly as subcutaneous nodules (Fig. 1A) or rapidly growing, asymptomatic, exophytic tumors with a smooth surface (Fig. 1B). In 3 cases, the lesion took the form of an exophytic tumor with an eroded surface (Fig. 1C and D), and in 1 case it manifested as an erythematous, scaly plaque with poorly defined borders. In 7 cases (63%), the main diameter of the primary tumor at diagnosis was >2cm (cT2). The physical examination at diagnosis revealed regional lymph node involvement in 4 patients; this was confirmed histologically with fine-needle aspiration. Satellite metastases were observed in another patient immediately after surgery of the primary tumor (Fig. 2A); therefore, 45% (5/11) had stage IIIB (pTNM) disease at diagnosis. Only 1 patient initially presented liver, lung, and bone metastases, which were confirmed using autopsy-based histopathology analysis (stage IV). The result of sentinel node biopsy performed in 2 patients was negative in one case and positive in the other. A third patient was programmed to undergo sentinel node biopsy, although this was rejected owing to migration of the radiotracer to 4 lymphatic territories in presurgical lymphoscintigraphy.

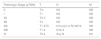

Patient Data.

| Sex | Age, y | Location | Size at Diagnosis | Additional Tests | Stage | Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 84 | Arm | 2.3cm | Lymph node | FNA+ | pIIIB | RS+RT |

| 2 | M | 81 | Concha (ear) | 2.5cm | Lymph node | FNA+ | pIIIB | RT |

| 3 | F | 82 | Knee | 2cm | Lymph node, metastasis | FNA+ | pIV | RS+CT |

| 4 | M | 60 | Forehead | 1cm | Satellite metastases | pIIIB | RS+RT/CT | |

| 5 | M | 78 | Thigh | 0.7cm | SLNB− | pI | RS | |

| 6 | F | 92 | Forehead | 5cm | Lymph node | FNA+ | pIIIB | RS+RT |

| 7 | M | 75 | Scalp | 5cm | Lost to follow-up | |||

| 8 | F | 79 | Hand | 1.5cm | Lymph node | FNA+ | pIIIB | RS |

| 9 | F | 81 | Scalp | 5cm | Lost to follow-up | RS | ||

| 10 | M | 81 | Leg | 1.1cm | SLNB+ | pIIIA | RS+RT | |

| 11 | F | 61 | Flank | 7cm | Lymphoscintigraphy | cIIA | RS+RT/CT |

Abbreviations: CT, chemotherapy; F, female; FNA, fine needle aspiration; M, male; RS, radical surgery; RT, radiotherapy; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

All patients but one (Fig. 1D) were candidates for local radical dissection, with clinical margins measuring between 1 and 3cm depending on the anatomical site. In all cases, histopathology revealed tumors comprising round discohesive cells with scant basophilic cytoplasm and nuclei with granular chromatin, several nucleoli, and abundant mitotic and apoptotic figures arranged mainly in solid nests (Fig. 2). The result of immunohistochemical staining was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 20 with perinuclear dot-like positivity and chromogranin in all cases (Fig. 2F). Findings for CK7 and thyroid transcription factor 1 were negative. The Ki-67 proliferation index was elevated in most cases. Lymphovascular invasion was observed in 7 of the 9 patients who underwent surgery (1 inoperable, 1 lost to follow-up after confirmatory biopsy) (Fig. 2E).

The only patient who was not a candidate for surgery underwent neoadjuvant local and regional radiotherapy. After surgery, a further 5 patients received adjuvant radiotherapy (2 local and 3 local and lymph node), and 3 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy (platins and etoposide as first line) (Fig. 2). However, 6 patients (54%) died because of their tumor, with a mean survival of 14.5 months and a median survival of 9 months (range, 3–45 months). A further 2 patients died of other causes (respiratory infection and liver failure) after more than 6 years of follow-up; 2 patients were lost to follow-up. Only 1 patient remains alive and disease-free after 23 months of follow-up.

Discussion and ConclusionsFirst described by Toker in 1972,1 MCC is an uncommon malignant neoplasm with a very aggressive clinical course. Its incidence is increasing, with the highest rates reported in Australia (1.6 cases per 100000 per year).2,3 The incidence in the USA and Europe stands at 0.18–0.41 cases per 100000 per year. Of the 2500 new cases expected per year in the European Union, 1000 patients are expected to die of the tumor.4–6 The incidence calculated in our series was 0.29–0.32 cases per 100000 per year, which is consistent with data reported from the literature in Europe. The only Spanish study that reported the incidence of MCC in Spain was a series of 19 cases from Gerona during 1995–2005 (1.3 cases per 100000 per year).7 The incidence we report in our series is lower than that reported in Gerona, probably because we only included cases from a single center, whereas those from the Gerona series included all cases recorded in the province.

MCC is a highly aggressive tumor that is often diagnosed in advanced stages. Depending on the published series, lymphatic spread is observed at diagnosis in up to 27–32% of patients.8,9 In fact, lymph node stage is the main prognostic factor, with survival rates 5 years after diagnosis of 51% in localized tumors and <14% in the case of distant metastasis.10,11 In the present series, lymph node involvement was observed in the physical examination at diagnosis in 4 patients (36.3%); this was confirmed using fine needle aspiration in all cases. Microscopic lymph node involvement was observed in approximately one-third of patients with clinically negative lymph nodes, thus indicating that fine needle aspiration is a minimally invasive staging tool. In our series, we were only able to consider fine needle aspiration in 3 patients owing to the advanced clinical stage in most cases. We believe that the high mortality rate we recorded is associated with advanced age (mean, 77.6 years), advanced stage disease (63.6% with stage pIIIA or higher at diagnosis), and, therefore, the high number of patients with lymph node involvement at diagnosis.

In 2009, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) developed the first consensus staging system after analyzing 5823 cases from the National Cancer Database, which was updated in 2017.8,12 At present, the eighth edition of the AJCC staging system differentiates between clinical stage and histopathological stage depending on the histological confirmation of the lymph node and/or distant metastases, respectively (Tables 2 and 3). Of particular interest in the present series was the advanced clinical and/or pathological stage recorded: in 7 patients the disease was stage pIIIA or higher at diagnosis (1 patient had stage pIIIA disease, 5 had stage pIIIB disease, and 1 patient had stage pIV disease). This is probably due to the size of the primary tumor (5 patients with tumors ≤5cm) and the high Ki-67 cell proliferation index, as evidenced by the histopathology study.

Clinical Classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (8th edition).a

| Clinical stage (cTNM) | T | N | M |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| IIA | T2-3 | N0 | M0 |

| IIB | T4 | N0 | M0 |

| III | T0-4 | N1-3 | M0 |

| IV | T0-4 | Any N | M1 |

Abbreviations: cN0, no regional lymph node metastasis on clinical or radiological examination; cN1, metastasis in regional lymph nodes; cN2, in-transit metastasis without lymph node metastasis; cN3, in-transit metastasis with lymph node metastasis; M0, no distant metastasis; M1a, metastasis to distant skin, distant subcutaneous tissue, or distant lymph nodes; M1b, metastasis to lung; M1c: metastasis to all other distant sites; Tis, in situ primary tumor; T0, no evidence of primary tumor; T1, maximum clinical tumor diameter ≤2cm; T2, maximum clinical tumor diameter >2 and ≤5cm; T3: maximum clinical tumor diameter >5cm; T4: primary tumor invades fascia, muscle, cartilage, or bone.

Pathologic Classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (8th Edition).

| Pathologic Stage (pTNM) | T | N | M |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| IIA | T2-3 | N0 | M0 |

| IIB | T4 | N0 | M0 |

| IIIA | T1-4T0 | N1a (sn) or N1aN1b | M0 |

| IIIB | T1-4 | N1b-3 | M0 |

| IV | T0-4 | Any N | M1 |

Abbreviations: M0, no distant metastasis; M1a, metastasis to distant skin, distant subcutaneous tissue, or distant lymph nodes; M1b, metastasis to lung; M1c, metastasis to all other distant sites; pN0, no regional lymph node metastasis detected on pathological evaluation; pN1a, clinically occult regional lymph node metastasis following lymph node dissection; pN1a (sn), clinically occult regional lymph node metastasis identified only by sentinel node biopsy; pN1b, clinically and/or radiologically detected regional lymph node metastasis; pN2, in-transit metastasis detected pathologically without lymph node metastasis; pN3, in-transit metastasis with lymph node metastasis detected pathologically; Tis, in situ primary tumor; T0, no evidence of primary tumor; T1, maximum clinical tumor diameter ≤2cm; T2, maximum clinical tumor diameter >2 and ≤5cm; T3, maximum clinical tumor diameter >5cm; T4, primary tumor invades fascia, muscle, cartilage, or bone.

There is no consensus on the most appropriate imaging techniques for the extension study in patients with MCC. Both the most recent American guidelines and the clinical practice guidelines of the Spanish Society of Dermatology and Venereology consider full-body positive emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) to be the imaging test of choice when evaluating tumor extension.13 Given that PET/CT was not available at our center, the extension study was carried out with CT in all cases.

When possible, treatment of MCC should include surgical removal with margins of 1–2cm. Despite the absence of prospective studies, significant differences in MCC have not been shown with respect to residual tumor, affected surgical margins, or overall survival.14 If the physical examination does not reveal lymph node involvement, surgical removal should be accompanied by sentinel node biopsy. Furthermore, if high-risk factors are present (tumor >1cm, affected or insufficient surgical margins, lymphovascular involvement, location in the head and neck), the current guidelines recommend administering radiotherapy at 50–66Gy to the tumor bed.15 In advanced stages, depending on whether there is dissemination to the lymph nodes and/or distant metastasis, it may be necessary to administer radiotherapy to the affected nodal basins and chemotherapy.

Avelumab is a monoclonal antibody against programmed death ligand 1 that was approved for the treatment of metastatic MCC by the United States Food and Drug Administration in March 2017 and by the European Medicines Agency in September 2017.16 We were unable to try this avelumab, since the last patient was diagnosed in February 2017, when the drug had not yet been authorized. Promising results have been reported for pembrolizumab and nivolumab, which are currently being evaluated in clinical trials.17,18

In conclusion, MCC is a very aggressive malignant neoplasm that is often diagnosed late. The authorization of new immunotherapy drugs has brought hope to patients with metastatic MCC.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García-Zamora E, Vela Ganuza M, Martín-Alcalde J, Miñano Medrano R, Pinedo Moraleda F, López-Estebaranz JL. Carcinoma de células de Merkel: estudio descriptivo de 11 casos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:63–68.