Within just 3 months of the detection in Wuhan in December 2019 of the first cases of pneumonia caused by a novel coronavirus, the scale of this outbreak has increased to pandemic proportions. As the number of cases increased, new respiratory, neurological, digestive, and dermatological clinical manifestations were also reported.1

A 29-year-old Colombian woman with no relevant history was seen at our emergency department for skin lesions that had appeared 1 week earlier. She had cough and fever that had begun 20 days earlier and for which she was not being treated. She reported no dyspnea and her baseline oxygen saturation was 97%. A laboratory workup revealed the following: D-dimer, 1 790.0 ng/mL; lymphocytes, 1 500/µL; lactate dehydrogenase, 202 U/L; C-reactive protein <0.5 mg/L. Chest x-ray was normal. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of a pharyngeal swab was positive for SARS-CoV-2.

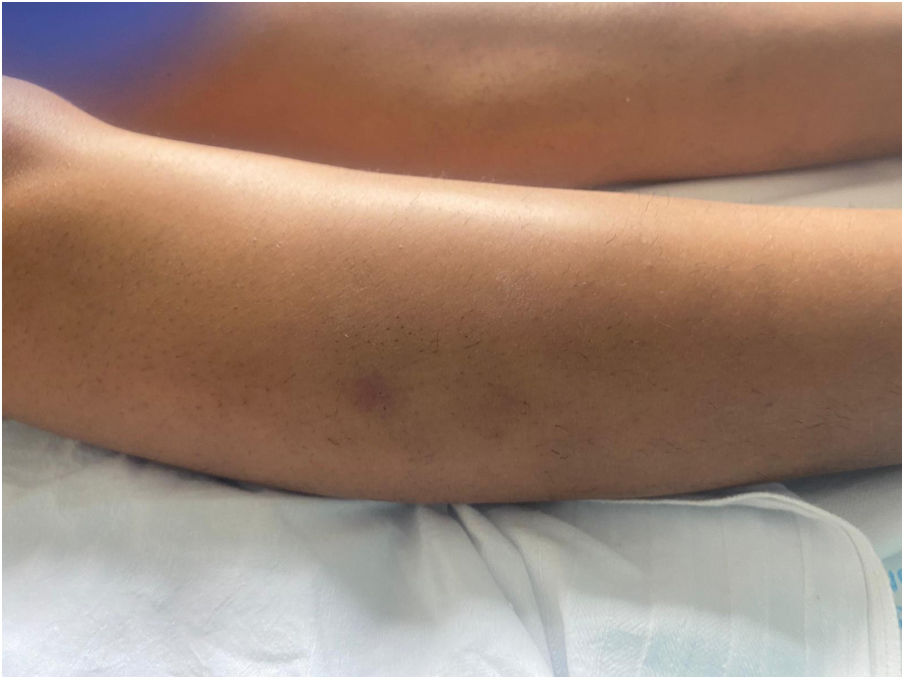

Physical examination revealed the presence of erythematous or brownish subcutaneous nodular lesions (1–4 cm). There were no other irregularities on the skin surface. The lesions, which were located on the anterior and lateral aspects of the legs (Fig. 1) and on the thighs, forearms, and left shoulder, were itchy and painful on palpation.

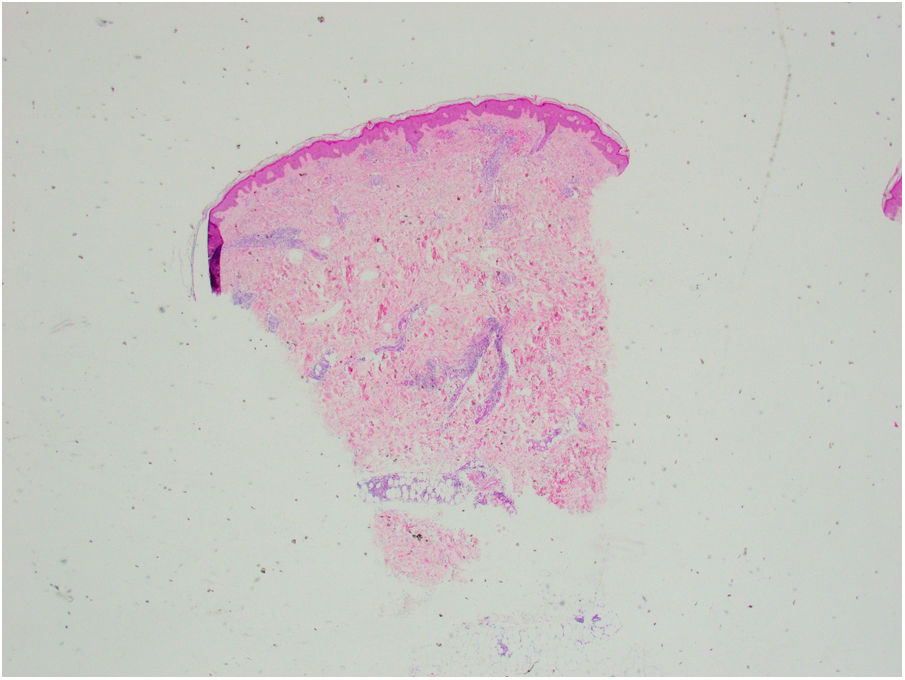

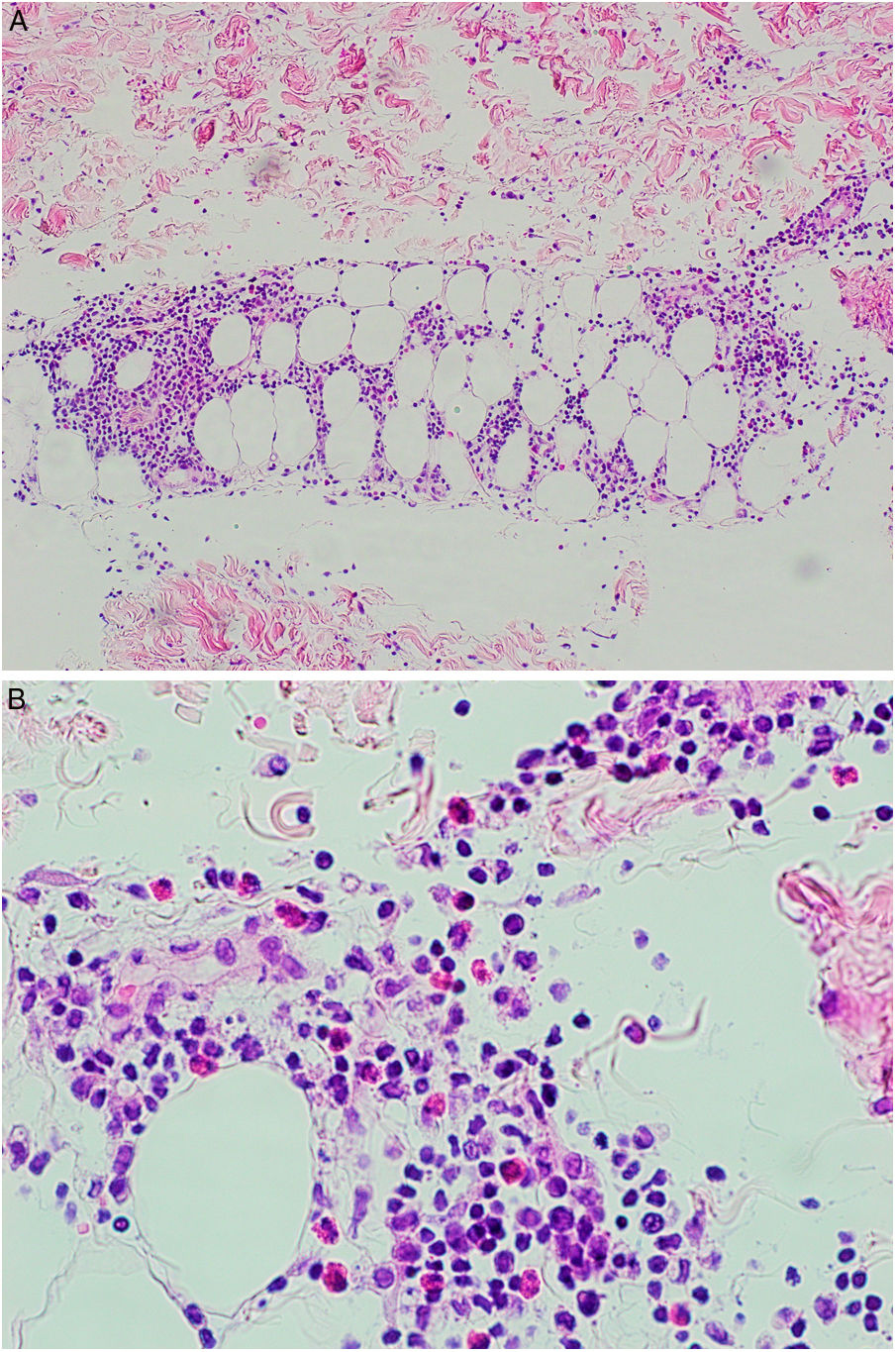

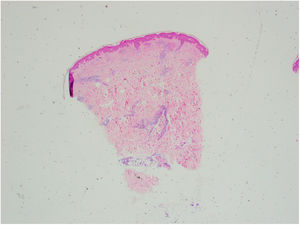

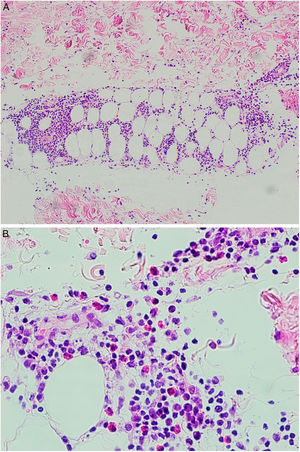

Skin biopsy of a lesion on the right leg showed no alterations in the epidermis. The superficial and deep dermis contained perivascular inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 2), which reached the subcutaneous tissue and displayed a predominantly lobular pattern (Fig. 3A). This infiltrate consisted of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils (Fig. 3B). Leukocytoclasia was evident. Flame figures were absent, and subcutaneous involvement was superficial, without fibrosis. Blood extravasation without vasculitis was observed.

Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with eosinophilic panniculitis secondary to COVID-19 infection.

She was hospitalized for observation, and began treatment with ceftriaxone, enoxaparin, and hydroxychloroquine. Betamethasone cream was prescribed for the skin lesions. The patient’s condition improved markedly within a few days, after which she was discharged from hospital and isolated at home.

Eosinophilic panniculitis is a very rare form of panniculitis. It affects women more frequently than men (3:1 ratio), and its incidence peaks in the third and sixth decades of life.2 It is a reactive process secondary to a range of stimuli, the most common of which are systemic diseases, including erythema nodosum, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, atopic dermatitis, lymphoma, insect bite-like eruptions,3 Kimura disease,4 and Wells syndrome.5 It has also been linked to certain drugs, including bee venom (which is used for immunotherapy) and penicillin,6 and to injection-site reaction following heparin administration.7

More relevant to the present case is the link between eosinophilic panniculitis and certain infections, including HIV, gnathostomiasis, streptococcus, and toxocariasis.8

Excessive production of cytokines, specifically interleukins IL-4 and IL-5, in response to these various stimuli has been proposed as a possible pathogenic mechanism, resulting in an abnormal immune response.2

With the progression of the COVID-19 pandemic, dermatologists began to describe different skin manifestations in affected patients.1,9,10 The most common are morbilliform, vesicular, urticarial, and petechial rashes, transient livedo reticularis, perniosis-like lesions, and ischemic acral lesions.

In our patient, the temporal correlation and the absence of other possible triggers suggest that the eosinophilic panniculitis was secondary to COVID-19 infection. The patient had not received subcutaneous heparin injections nor any other specific treatments before the appearance of the lesions.

In COVID-19 infection, like so many other conditions, cutaneous alterations reflect an underlying internal disease. It is therefore important to make good use of the skin’s accessibility and to biopsy any new lesions observed, as the information obtained can help us understand the pathogenesis of the infection and select the most effective treatment.

Please cite this article as: Leis-Dosil VM, Sáenz Vicente A, Lorido-Cortés MM. Paniculitis eosinofílica secundaria a infección por COVID-19. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2020.05.003