Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) are designed to help health professionals provide patients with excellent medical care. The last critical appraisal of CPGs on the treatment of psoriasis evaluated publications up to 2009, but several new guidelines have been published since and their methodological quality remains unclear.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study was to systematically evaluate the quality of CPGs on the treatment of psoriasis published between 2010 and 2020 using the Appraisal Guidelines Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) tool.

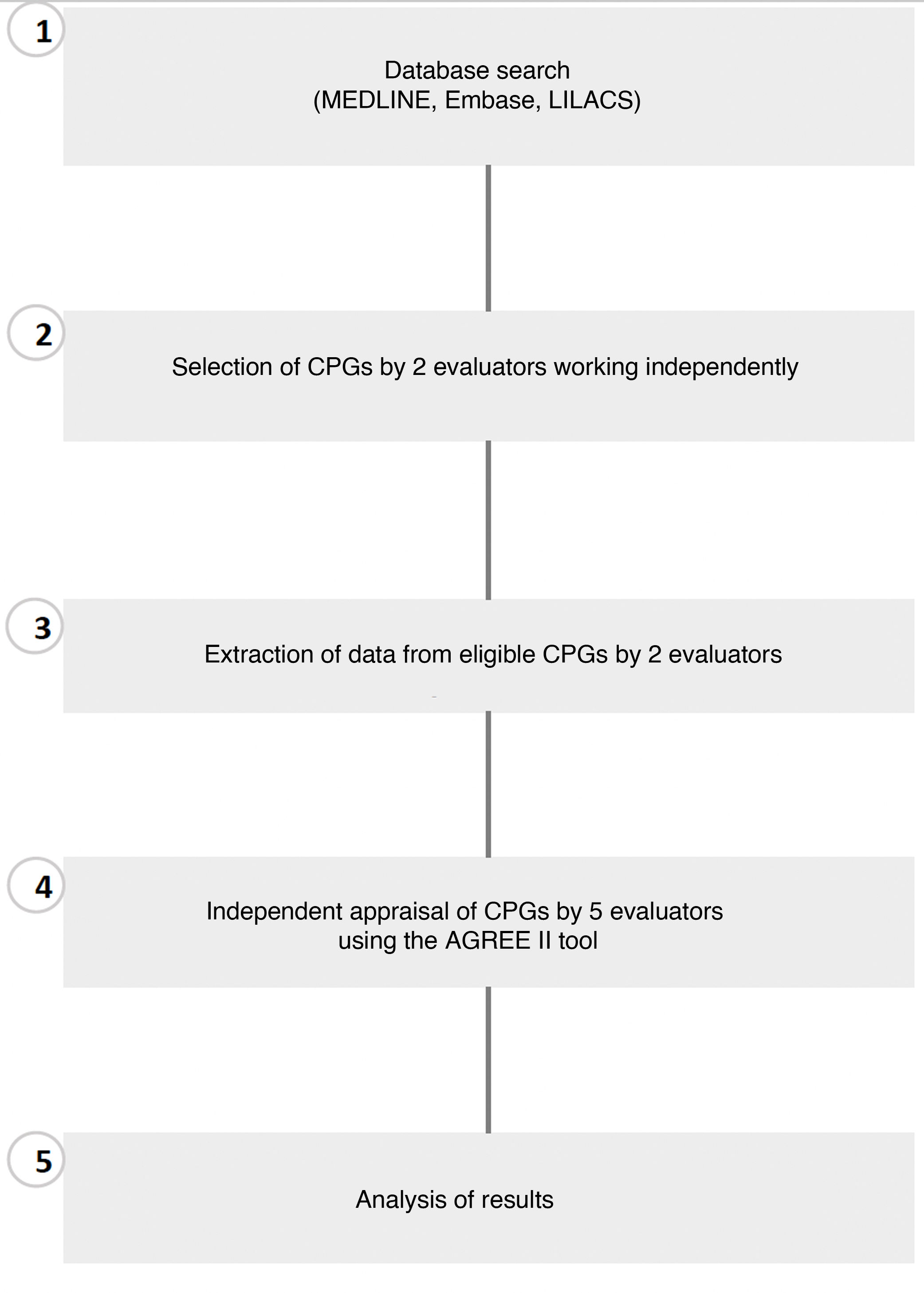

Material and methodsWe searched for relevant CPGs in MEDLINE, Embase, and LILACS (Latin American and Caribean Health Sciences Literature) as well as in the gray literature. Two reviewers working independently selected the guidelines for analysis and extracted the relevant data. Each guideline was then assessed using the AGREE II instrument by 5 reviewers, also working independently.

ResultsNineteen CPGs met the inclusion criteria and most of them had been produced in high-income countries. The mean (SD) domain scores were 84.9% (14.7%) for scope and purpose, 65.5% (19.3%) for stakeholder involvement, 66.7% (15.6%) for rigor of development, 72.8% (16.8%) for clarity of presentation, 46.6% (21.7%) for applicability, and 57.0% (30.4%) for editorial independence.

ConclusionsAlthough about three-quarters of the CPGs assessed were judged to be of high quality and over half were recommended for use in clinical practice, standards of guideline development need to be raised to improve CPG quality, particularly in terms of applicability and editorial independence, which had the lowest scores in our evaluation.

Las guías de práctica clínica (GPCs) se han desarrollado para apoyar a los profesionales de la salud a brindar una excelente atención médica a sus pacientes. Varias GPCs para el tratamiento de psoriasis se han desarrollado desde la última evaluación de calidad de GPCs publicada en 2009 y hasta el momento su calidad metodológica es poco clara.

ObjetivoEvaluar sistemáticamente la calidad de GPCs para el tratamiento de psoriasis publicadas en el periodo de 2010-2020, utilizando el instrumento Appraisal Guidelines Research and Evaluation (AGREE II).

Material y métodosSe realizaron búsquedas de GPCs en bases de datos, incluyendo MEDLINE, Embase, LILACS y en la literatura gris. La selección de GPCs y la extracción de datos se realizó de forma independiente por dos revisores. Cinco revisores, aparte, evaluaron las GPCs usando el instrumento AGREE II.

ResultadosDiez y nueve GPCs cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión, en su mayoría desarrolladas en países de altos ingresos. Las puntuaciones medias de los dominios fueron: alcance y propósito (84,9%±14,7%), participación de las partes interesadas (65,5%±19,3%), rigor del desarrollo (66,7%±15,6%), claridad de presentación (72,8%±16,8%), aplicabilidad (46,6%±21,7%), e independencia editorial (57,0%±30,4%).

ConclusionesA pesar de que tres cuartos del total de GPCs incluidas fueron clasificadas como de alta calidad y más de la mitad de ellas se recomendaron para la práctica clínica, el desarrollo de las GPCs todavía debe optimizarse para mejorar su calidad. Especialmente en su aplicabilidad e independencia editorial, los cuales fueron los dominios con la puntuación más baja.

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated skin disease with genetic associations. It is characterized by sustained inflammation leading to uncontrolled keratinocyte proliferation and dysfunctional differentiation.1 Psoriasis has both a physical and psychological impact that results in diminished patient quality of life.2

It has been estimated that the incidence of psoriasis varies by age and geographic location.3 As a chronically remitting and relapsing disease, it requires long-term treatment with topical agents (corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D derivatives), which, depending on disease severity, comorbidities, and healthcare access, may or may not be combined with systemic therapies (methotrexate, cyclosporine, retinoids, biologic agents).1 Several clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) have been developed to reduce variability in treatment recommendations for psoriasis.4–6 CPGs are “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances”.7 Their development is both costly and laborious, and potential benefits depend on the quality of the guidelines.8

Proper guideline implementation hinges on rigorous development methodology and strategies.9,10 Organizations such as the Institute of Medicine, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, the World Health Organization, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, and the Guidelines International Network provide useful resources for helping guideline developers produce higher-quality recommendations.11 Despite a growing body of resources, however, suboptimal CPG quality, poor adherence, and variability in recommendations remain a problem,10,12 hence the importance of assessing the methodology used for development. Tan et al.13 performed a critical appraisal of psoriasis CPGs published between 2006 and 2009. Since then, however, new guidelines have appeared while others have been updated. The aim of this study was to perform a systematic appraisal of the methodological quality of CPGs on the treatment of psoriasis published in the past decade using the Appraisal Guidelines Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) tool.

MethodsInclusion and Exclusion CriteriaThe protocol for this critical appraisal of CPGs on psoriasis is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42018103075). We included a) CPGs on the treatment of psoriasis published between 2010 and 2020 and b) CPGs that included explicit mention of the search strategy employed and the methods used to reach recommendations. No language restrictions were applied. We excluded: a) expert consensus documents and b) CPGs with incomplete descriptions of the search strategy and/or the methods used to reach recommendations.

Search StrategiesThe searches were performed in electronic health sciences databases, with no limits placed on language of publication. Three databases were searched:

- •

MEDLINE (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/); searched between 1946 and July 16, 2020.

- •

Embase (Elsevier.com); searched between 1974 and July 16, 2020.

- •

LILACS (https://lilacs.bvsalud.org/es/); search performed on July 16, 2020.

We also performed a manual search of professional organization websites and journals. The database search was updated on August 2021. Details of the search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

CPG SelectionTo check the reliability of the CPG selection process, 2 evaluators (AA and CM) separately screened the titles and abstracts of 20% of all articles retrieved by the search to check that they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Interrater agreement was calculated using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) with a 95% CI. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third evaluator (AV). AA and CM then screened the remaining 80% of articles and again, any discrepancies were resolved by AV. The 2 evaluators performed a full-text review of all articles meeting the inclusion criteria to check their eligibility.

Data ExtractionTwo evaluators separately extracted the following information from each CPG included in this critical appraisal: title, year of publication, organization that developed the CPG, funding source, methods for assessing the quality and strength of the scientific evidence, methods for formulating recommendations, and country and language of publication. All data used and analyzed during the study are available upon request.

Quality AppraisalThe quality of the CPGs included was evaluated using AGREE II,14,15 a tool designed to evaluate CPG development and reporting.16 It has 23 items organized into 6 domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence (Table 1). All items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree“to “strongly agree”. In addition to these 6 domains, AGREE II has 2 general assessment items: one to rate the overall quality of the guideline and the other to make a recommendation for use or not.

Domains and Items in the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II Tool.15

| Domain | Items |

|---|---|

| Domain 1. Scope and purpose | The overall objective(s) of the guideline is (are) specifically described.The health question(s) covered by the guideline is (are) specifically described.The population (patients, public, etc.) to whom the guideline is meant to apply is specifically described. |

| Domain 2. Stakeholder involvement | The guideline development group includes individuals from all the relevant professional groups.The views and preferences of the target population (patients, public, etc.) have been sought.The target users of the guideline are clearly defined. |

| Domain 3. Rigor of development | Systematic methods were used to search for evidence.The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described.The strengths and limitations of the body of evidence are clearly described.The methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described.The health benefits, side effects, and risks have been considered in formulating the recommendations.There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence.The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication.A procedure for updating the guideline is provided. |

| Domain 4. Clarity of presentation | The recommendations are specific and unambiguous.The different options for management of the condition or health issue are clearly presented.Key recommendations are easily identifiable. |

| Domain 5. Applicability | The guideline describes facilitators and barriers to its application.The guideline provides advice and/or tools on how the recommendations can be put into practice.The potential resource implications of applying the recommendations have been considered.The guideline presents monitoring and/or auditing criteria. |

| Domain 6. Editorial independence | The views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline.Competing interests of guideline development group members have been recorded and addressed. |

| Overall guideline assessment | Rate the overall quality of this guideline.I would recommend this guideline for use |

In an initial step, 5 evaluators assessed 2 CPGs using the AGREE II tool until an ICC of 60% was reached; the remaining CPGs were independently reviewed by 2 of the 5 evaluators. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus and, when this was not possible, a third evaluator intervened.

Data AnalysisA descriptive analysis was performed to summarize the following information: year of publication, type of organization that developed the CPG, funding source, methods for evaluating the quality and strength of the scientific evidence, methods for formulating recommendations, and country and language of publication.

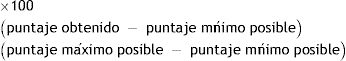

The quality of each CPG was determined by adding up the scores for each of the 6 domains. Domain scores were calculated by adding up the scores of each item in the domain and scaling the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score for the domain. The formula used is shown below:

The AGREE II tool does not establish minimum and maximum scores for assessing domain quality, making it difficult to distinguish between high- and low-quality guidelines.17 Nonetheless, following the lead of authors of other critical appraisals,17–19 we considered that domains with a score of more than 60% were effectively addressed and that CPGs with 3 or more domains scoring more than 60%, including rigor of development, were of high quality.17–21

ICCs with a 95% CI were calculated to assess interrater agreement for each of the 23 items in the AGREE II tool.22 Results were interpreted using the scale proposed by Landis and Koch, where a score of 0.01–0.20 indicates slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 substantial agreement, and 0.81–1.00 very good agreement.23 The statistical package SPSS (v.22.0) was used for the descriptive and statistical analyses (Fig. 1).

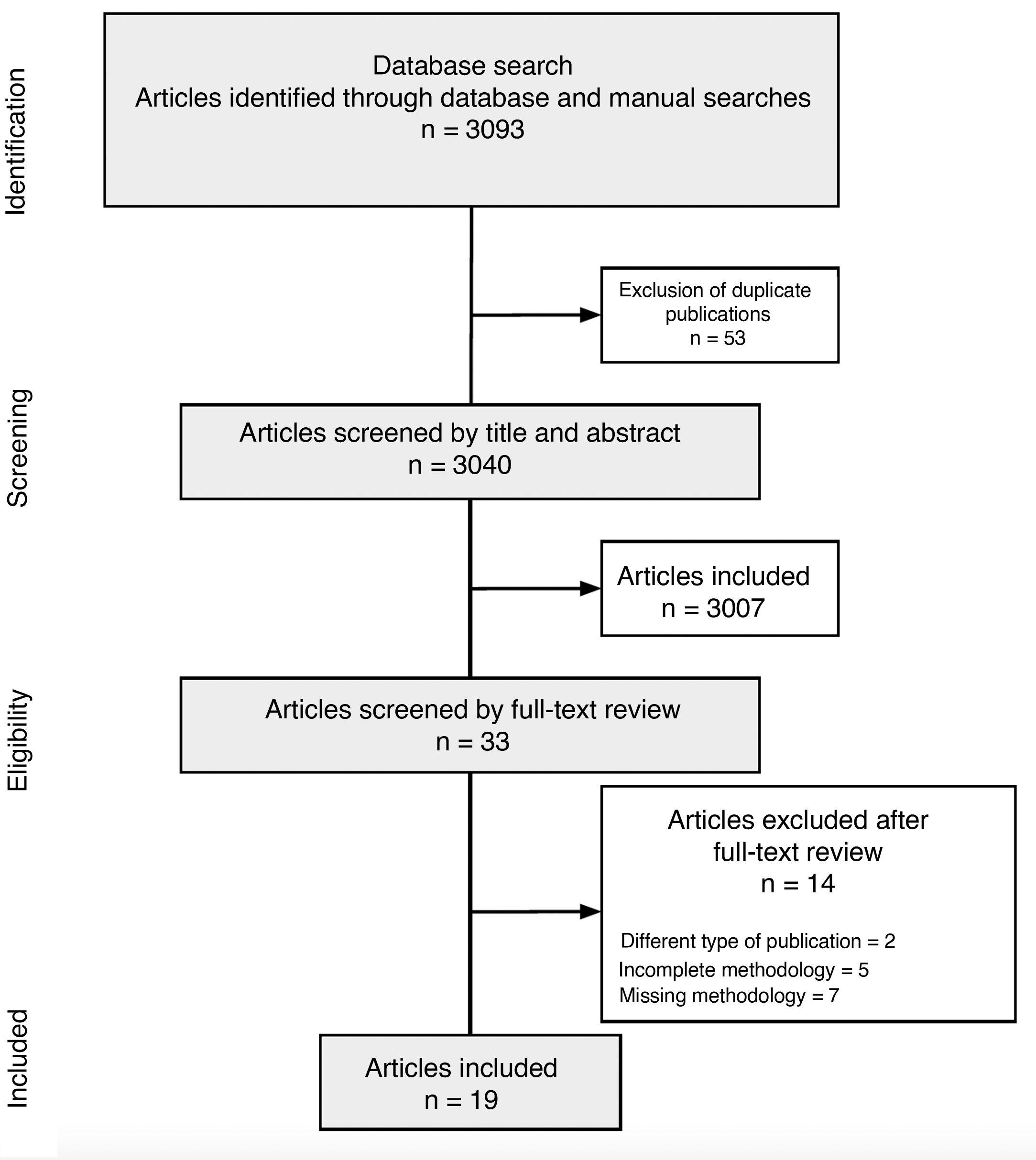

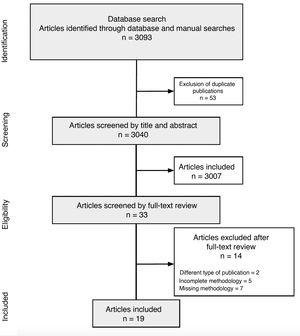

ResultsCPG CharacteristicsThe search retrieved 3093 articles, of which 3040 remained after deduplication. Title and abstract screening identified 33 CPGs for full-text review. Of these, 19 were deemed eligible and included in this critical appraisal.24–26 The search strategy and results are summarized in a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow chart (Fig. 2).

The 19 CPGs analyzed were published between 2010 and 2020. Three were from the United Kingdom, 2 each from Italy and the Netherlands, and 1 each from France, Colombia, Mexico, Japan, Malaysia, Germany, Spain, China, the United States, Ukraine, and Denmark. There was also 1 CPG jointly developed by several Latin American countries. Twelve guidelines were published in English, 2 in Spanish, and 1 each in Italian, Dutch, Danish, Ukrainian, and German (Table 2).

Characteristics of Clinical Practice Guidelines Analyzed in Critical Appraisal.

| Guideline | Organization | Year of publication | Country, language | Income classification59 | Health care system | Methods for assessing quality and strength of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amatore et al.24 | SFDermato | 2019 | France, English | High income | Etatist social health insurance58 | GRADE |

| González, Londoño, & Cortés35 | ASOCOLDERMA and ColPsor | 2018 | Colombia, Spanish | Upper-middle income | Multiple insurers 60 | GRADE and AMSTAR |

| CENETEC34 | CENETEC | 2013 | Mexico, Spanish | Upper-middle income | Multiple insurers60 | 1. NICE and SIGN. 2. Classification system for psoriasis management clinical practice guidelines; 3. DDG system; 4. Modified Shekelle scale |

| Fujita et al.33 | MoHLW | 2018 | Japan, English | High income | Etatist social health insurance58 | Japanese Dermatological Association Clinical Practice Guidelines for Skin Malignancy |

| Gisondi et al.36 | SIDeMaST | 2017 | Italy, English | High income | National health service58 | GRADE and Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions |

| ADOI and ISS32 | ADOI, ISS and Italian MoH | 2016 | Italy, English | High income | National health Service58 | NICE |

| MoH Malaysia, MDS, and AoM31 | MoH of Malaysia, MDS, and AoM | 2013 | Malaysia, English | Upper-middle income | Multiple insurers and national health service61 | Canadian Preventive Services Task Force 2001 and SIGN |

| Nast et al.37 | AWMF | 2021 | Germany, German | High income | Social health insurance58 | GRADE |

| NICE30 | NICE | 2012 | United Kingdom, English | High income | National health service58 | GRADE |

| Puig et al.39 | AEDV | 2013 | Spain, English | High income | National health service58 | Own classification system |

| SIGN29 | SIGN | 2010 | United Kingdom, English | High income | National health service58 | SIGN |

| Smith et al.28 | BAD | 2020 | United Kingdom, English | High income | National health service58 | GRADE |

| Van der Kraaij et al.25 | NVDV | 2017 | Netherlands, English | High income | Etatist social health Insurance58 | GRADE |

| Zhou et al.27 | BUCM | 2014 | China, English | Upper-middle income | Social health insurance58 | 1. Cochrane Handbook of Systemic Reviews of Interventions; 2. Oxford CEBM levels of evidence; and 3. Evidence system for traditional Chinese medicine and recommendations for its classification |

| Elmets et al.40,41; Menter et al.42–44 | AAD and NPF | 2020 | US, English | High income | Private health system | SORT |

| Kogan et al.45 | SOLAPSO | 2019 | Argentina, Uruguay, El Salvador, Cuba, Chile, Mexico, Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, Costa Rica, Honduras, Bolivia; English | High income, upper-high income, low income | Multiple insurers and national health service60 | GRADE |

| MoH Ukraine46 | MoH Ukraine | 2015 | Ukraine, Ukrainian | Lower-middle income | National health service62 | 1. SIGN; 2. AAS Levels of Evidence guidelines; 3. German levels of evidence and strength of recommendation; 4. GRAPPA guidelines classification of evidence and recommendations. |

| DNBH26 | DNBH | 2015 | Denmark, Danish | High income | National health service58 | GRADE |

| Van Peet et al.38 | NHG | 2014 | Netherlands, Dutch | High income | Etatist social health insurance58 | Not specified |

Abbreviations: AAD, American Academy of Dermatology; AAS, American Academy of Science; ADOI, Associazione Dermatologi Ospedalieri Italiani; AEDV, Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; AMSTAR, Appraising the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews; AoM, Academy of Medicine of Malaysia; BAD, British Association of Dermatologists; BUCM, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; CEBM, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; DDG, Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft; DNBH, Danish National Board of Health; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations; GRAPPA, Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis; ISS; Istituto superiore di sanità; MDS; Malaysian Dermatological Society; MoH, Ministry of Health; MOHLW, Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; NHG, Dutch College of General Practitioners; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NPF, National Psoriasis Foundation; NVDV, Dutch Society for Dermatology and Venerology; SiDeMaST, Italian Society of Dermatology and Venereology; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; SOLAPSO, Latin American Psoriasis Society; SORT, Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy.

Nine of the guidelines were produced by dermatology societies, academies, or associations; 3 by dermatology societies or associations in collaboration with a ministry of health; 3 by a health institute; and 1 each by an academy and a health institute, a ministry of health, and a university (Table 2).

The guidelines were funded by dermatology societies, academies, or associations4,25; government26–34; or the pharmaceutical industry.35 No funding body was specified for the other CPGs.36–46

Thirteen (68.4%) of the CPGs were developed in a high-income country, 4 (21.0%) in an upper-middle income country, 1 (5.3%) in a lower-middle income country, and 1 (5.3%) in a group of countries with different income levels (Table 2). Nine CPGs (47.4%) mentioned using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) framework. Most guidelines provided recommendations for the treatment of mild to severe psoriasis vulgaris and proposed the use of combined systemic therapy (topical corticosteroids, retinoids, methotrexate, and biologics) in patients with certain risk factors and comorbidities.

Quality EvaluationThe overall level of interrater agreement using the AGREE II appraisal tool was an ICC of 0.621 with a 95% CI. Fourteen 14 CPGs (74%) were rated as high quality and 5 (26%) as low quality based on the criteria described in the Methods section (Table 3). The scaled domain scores, overall score, and general recommendation for each CPG are shown in Table 3. The mean domain scores for all the CPGs are shown in Table 4.

Standardized AGREE II Scores by Domain.

| Guideline | Scope and purpose, % | Stakeholder involvement, % | Rigor of development, % | Clarity of presentation, % | Applicability, % | Editorial independence, % | Overall score | Overall recommendation | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amatore et al.24 | 88.9 | 83.3 | 70.8 | 91.7 | 56.3 | 54.2 | 6.0 | Recommended with modifications | High |

| González et al.35 | 97.2 | 83.3 | 60.4 | 86.1 | 52.1 | 33.3 | 6.0 | Recommended with modifications | High |

| CENETEC34 | 100 | 58.3 | 62.5 | 55.6 | 54.2 | 37.5 | 3.5 | Not recommended | Low |

| Fujita et al.33 | 86.1 | 22.2 | 54.2 | 91.7 | 8.3 | 83.3 | 4.5 | Not recommended | Low |

| Gisondi et al.36 | 88.9 | 63.9 | 65.6 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 100 | 4.0 | Not recommended | High |

| ADOI and ISS32 | 94.4 | 72.2 | 70.8 | 58.3 | 33.3 | 75.0 | 4.5 | Recommended with modifications | High |

| MoH Malaysia, MDS, and AoM31 | 86.1 | 55.6 | 63.5 | 88.9 | 70.8 | 54.2 | 5.0 | Recommended with modifications | High |

| Nast et al.37 | 77.8 | 63.9 | 87.5 | 63.9 | 54.2 | 91.7 | 5.5 | Recommended | High |

| NICE30 | 100 | 94.4 | 92.7 | 100 | 77.1 | 83.3 | 6.0 | Recommended | High |

| Puig et al.39 | 55.6 | 47.2 | 34.3 | 66.7 | 47.9 | 12.5 | 3.5 | Not recommended | Low |

| SIGN29 | 100 | 80.6 | 87.5 | 91.7 | 81.3 | 41.7 | 5.5 | Recommended | High |

| Smith et al.28 | 91.7 | 72.2 | 88.5 | 91.7 | 75.0 | 83.3 | 6.5 | Recommended | High |

| Van der Kraaij et al.25 | 77.8 | 80.6 | 64.6 | 80.6 | 18.8 | 29.2 | 5.0 | Recommended with modifications | High |

| Zhou et al.27 | 72.2 | 80.6 | 68.8 | 63.9 | 22.9 | 91.7 | 4.5 | Recommended with modifications | High |

| Elmets et al.40,41 Menter et al.42,43,44 | 80.6 | 47.2 | 62.5 | 58.3 | 39.6 | 87.5 | 4.5 | Recommended with modifications | High |

| Kogan et al.45 | 91.7 | 58.3 | 61.5 | 66.7 | 18.8 | 4.2 | 5.0 | Recommended with modifications | High |

| MoH Ukraine46 | 88.9 | 80.6 | 58.3 | 72.2 | 60.4 | 20.8 | 4.5 | Recommended with modifications | Low |

| DNBH26 | 91.7 | 72.2 | 75.0 | 61.1 | 43.8 | 70.8 | 5.5 | Recommended with modifications | High |

| Van Peet et al.38 | 44.4 | 27.8 | 37.5 | 44.4 | 20.8 | 29.2 | 2.5 | Not recommended | Low |

Abbreviations: ADOI, Associazione Dermatologi Ospedalieri Italiani; AGREE II, Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; AoM, Academy of Medicine of Malaysia; DNBH, Danish National Board of Health; ISS; Istituto superiore di sanità; MDS, Malaysian Dermatological Society; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

Mean quality ratings for clinical practice guidelines analyzed by AGREE II domain.

| Domain | Mean quality rating |

|---|---|

| Scope and purpose | 84.9% |

| Stakeholder involvement | 65.5% |

| Rigor of development | 66.7% |

| Clarity of presentation | 72.8% |

| Applicability | 46.6% |

| Editorial independence | 57.0% |

Abbreviation: AGREE II, Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II Tool.

The scope and purpose domain evaluates the overall objective of the CPG, the health questions posed, and the target population.15 The mean (SD) score was 84.9% (14.7%); 17 CPGs (90%) scored more than 60% in this domain (Table 3).

Domain 2: Stakeholder InvolvementThe stakeholder involvement domain evaluates the participation of different stakeholders in the development of the guideline by looking at the make-up of the development group and consideration of target user views and preferences.15 The mean (SD) score was 65.5% (19.3%) and 12 CPGs (63%) scored more than 60% in this domain (Table 3).

Domain 3: Rigor of DevelopmentThe rigor of development domain considers the procedure used to search for and synthesize the evidence, the methods used to formulate recommendations, and the procedure for updating the guideline.15 The mean (SD) score was 66.7% (15.6%) and 15 CPGs (79%) scored more than 60% (Table 3).

Domain 4: Clarity of PresentationThe clarity of presentation domain looks at guideline structure and format and also considers the language used.15 The mean (SD) score in this domain was 72.8% (16.8%) and 14 CPGs (74%) scored more than 60% (Table 3).

Domain 5: ApplicabilityThe applicability domain considers potential facilitators and barriers to implementation, monitoring strategies, and implications for adherence to recommendations and resources.15 The mean (SD) score was 46.6% (21.7%). This was the only domain with non-normally distributed scores; the mean value was 50 and the range was 8.3% to 81.3%. Only 5 CPGs (26%) scored more than 60% in this domain (Table 3).

Domain 6: Editorial IndependenceThe editorial independence domain addresses issues of transparency and potential biases introduced by funders and developers in the formulation of recommendations.15 The mean (SD) score in this case was 57.0% (30.4%); 9 CPGs (47%) scored more than 60% (Table 3).

Overall Guideline AssessmentFour of the 19 GPCs (21%) were recommended by the evaluators,28,37 10 (53%) were recommended with modifications,24,31,32,35,40–46 and 5 (26%) were not recommended (Table 3).33,34,36,38,39 The 4 recommended GPCs scored at least 60% in most domains and had been developed in the United Kingdom; the 5 guidelines that were not recommended scored less than 60% in most domains and were from Mexico, Japan, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands (Table 3). Most of the CPGs were classified as high quality.

DiscussionCPGs are useful tools for bridging the gap between the growing number of scientific publications and daily clinical practice; they help physicians make decisions about their patients.47 Numerous guidelines have been published in the field of dermatology, but their quality must be assessed to ensure adequate implementation. In this study, we systematically appraised the quality of 19 CPGs on the treatment of psoriasis. Three-quarters of the CPGs included were classified as high quality and more than half were recommended for use in clinical practice. The quality rating contrasts with findings for CPGs on the treatment of other skin diseases, such as acne and dermatitis, which have been rated as low quality.48–50

The highest-scoring AGREE II domains in our study were scope and purpose and clarity of presentation. At the other end of the scale were applicability and editorial independence. Similar results were reported in a critical appraisal of 8 CPGs on the management of psoriasis vulgaris13 and quality assessments of CPGs on atopic dermatitis51 and acne.52 Low applicability scores have been attributed to limited discussion of organizational barriers and gaps between the formulation of recommendations and implementation processes.11,13 There would, therefore, appear to be certain discrepancies between the real-life applicability of CPGs and the evidence-based recommendations they include. As suggested in a study of CPGs on acne, appraisals might also be influenced by subjective judgments about implementation processes or adherence.52

In addition to evaluating the quality of the CGPs according to the different domains of the AGREE II tool, we classified CPGs as low- or high-quality using a scoring system that provides greater weight to rigor of development (Table 3). This system has been used in several studies53 and considers studies with an AGREE II score of 60% or higher to be of high quality. It is considered to be methodologically sound as the rigor of development domain has been found to have the strongest influence on overall assessment of guideline quality.54,55 Accordingly, assessments of overall quality and recommendation for use may not always be consistent with high- or low-quality ratings based on the cutoff score of 60%.36 The Italian guidelines on plaque psoriasis,36 for example, received a low overall score and were not recommended for use, but because they scored 60% or more in 4 domains, including rigor of development, they were classified as high-quality (Table 3).

Most of the CPGs were developed in high-income countries using rigorous guideline development methodologies. Lower AGREE scores have been reported for guidelines developed in low- and middle-income countries (e.g., Latin American countries).56 The applicability domain, with a mean score of 46.6%, was the lowest-scoring domain in our critical appraisal, supporting findings from other independent assessments, even of high-quality CPGs in the field of dermatology.57 Addressing the aspects covered in the applicability domain is important for the development of higher-quality CPGs, which should also consider the health care system in place in the target area and include recommendations that take into account variability in health care needs and accessibility. Most of the CPGs analyzed were developed in countries with largely government-run health care systems, financed by the state or society. Examples are etatist social health insurance programs and national health services. Other CPGs, however, were developed in countries with insurance-based systems (multiple insurers, social health insurance, and national health insurance) or private health systems, where health care regulation varies geographically, socially, and sectorially and where financing and service delivery lie mainly in the hands of for-profit providers (Table 2).

This study has several limitations. First, the evaluators found it difficult to distinguish between the scores of 3, 4, and 5 on the 7-item scale because the updated AGREE II tool only provides a clear definition for items 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree); the tool has been assessed several times since its development.14,15 Variations in interpretation constitute a potential source of reporting bias, although interrater agreement was high (ICC, 0.621). Second, even though we applied a comprehensive search strategy, with no language restrictions, we may have missed CPGs registered in databases for other languages or published by private organizations (e.g., a nonindexed CPG developed for a specific institutional purpose). Third, we did not include CPGs on psoriatic arthritis, which is an important treatment component in psoriasis.

Our study also has some strengths. First, we used a robust search strategy adapted to several databases and open to all languages to avoid language bias. Second, the critical appraisal was performed by an interdisciplinary team of dermatologists and methodologists to achieve a balance between methodological and clinical applicability issues. Third, we checked interrater agreement using a selection of the articles analyzed and statistically assessed interrater differences with the aim of improving agreement in the overall assessment. Fourth, we analyzed CPGs published between 2010 and 2020 to address improvements and new treatment options that have been made available for different types of psoriasis since the first critical appraisal of CPGs on psoriasis was published in 2010.13 Finally, we used the latest version of the AGREE II tool, which is a well-known and widely accepted methodological tool for assessing CPG quality.

Our updated search in August 2021 retrieved the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) guidelines on the management of psoriasis during the COVID-19 pandemic (versions 163 and 264). Although these guidelines did not meet the methodological criteria for inclusion, their content is highly relevant, as the NPF created a COVID-19 task force to produce guidance on prevention, clinical decision-making, and optimization of general measures in psoriasis patients undergoing treatment (phototherapy); the aim was to reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The guidelines include several important pandemic-related recommendations supported by strong evidence. First, patients without contraindications to vaccination should be administered an mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it becomes available while continuing to receive systemic treatment (oral or biologic agents) and decisions regarding changes to treatment regimens for the administration of the vaccine should be taken on a case-by-case basis. Second, patients should continue to receive the inactivated influenza virus. Third, patients without SARS-CoV-2 infection should continue to receive biologic or oral treatments for psoriasis. Fourth, psoriasis patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 should be managed using the same protocols as those applied to the general population, but their care should involve a multidisciplinary approach, with consultation of dermatologists, rheumatologists, and infectious disease specialists. Fifth, antimalarials and ivermectin are not recommended for the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The updated CPGs published by Nast el al. in 202065 and 202166 provide additional recommendations on the use of new systemic therapies, with a focus on biologics (interleukin 17 and 23) that had been approved for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis vulgaris in Europe. These guidelines compared the clinical effectiveness of different biologics using network meta-analysis and formulated recommendations on the treatment of psoriasis in the context of the pandemic. Likewise, the updated British Association of Dermatologists guidelines on the use of biologic therapy for psoriasis published by Smith et al67 in 2020 recommend using new biologics that have already been licensed or are expected to be licensed for use in the United Kingdom, such as certolizumab pegol, ixekizumab, and tildrakizumab for adult and pediatric populations.

ConclusionsTo summarize, most of the psoriasis CPGs analyzed in this critical appraisal can be considered high-quality guidelines, although we did detect shortcomings in the domains of applicability and editorial independence. Our findings also revealed continuing gaps in CPG development between high- and low-income countries. The applicability of CPGs needs to be improved. Guideline developers need to consider the target health care system(s) to ensure that the recommendations they include are viable and can be successfully implemented.

FundingThis study did not receive any funding from the public or private sector or any not-for-profit associations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Yasser Amer received support from the Research Chair for Evidence-Based Health Care and Knowledge Translation, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

The authors thank Gabriela Villavicencio and Nathaly Bonilla for their help with the translation into Spanish of the original manuscript.