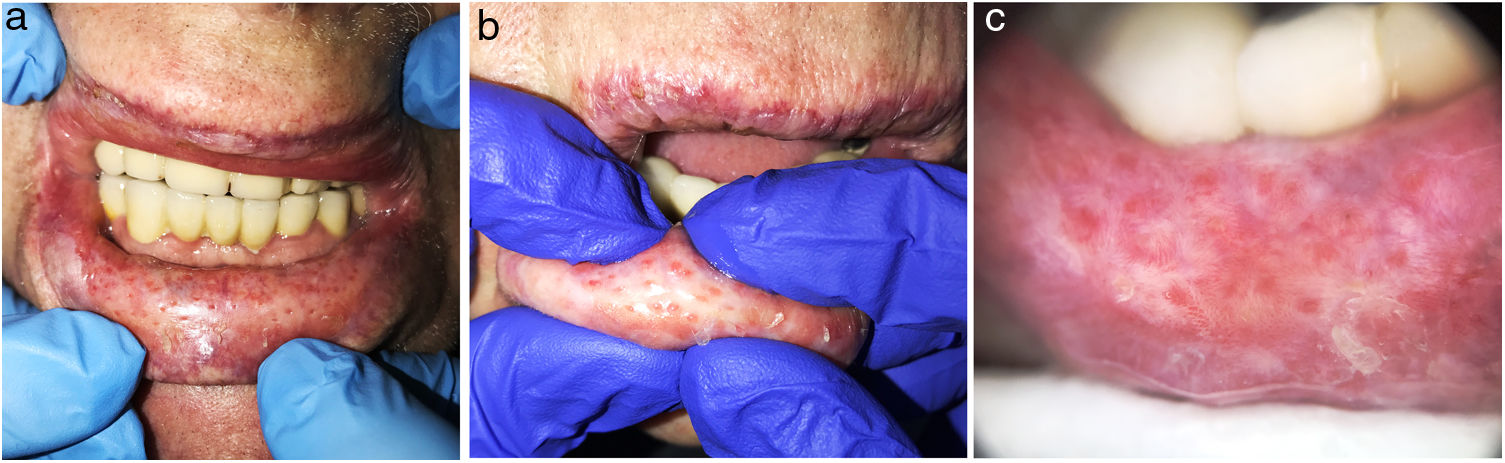

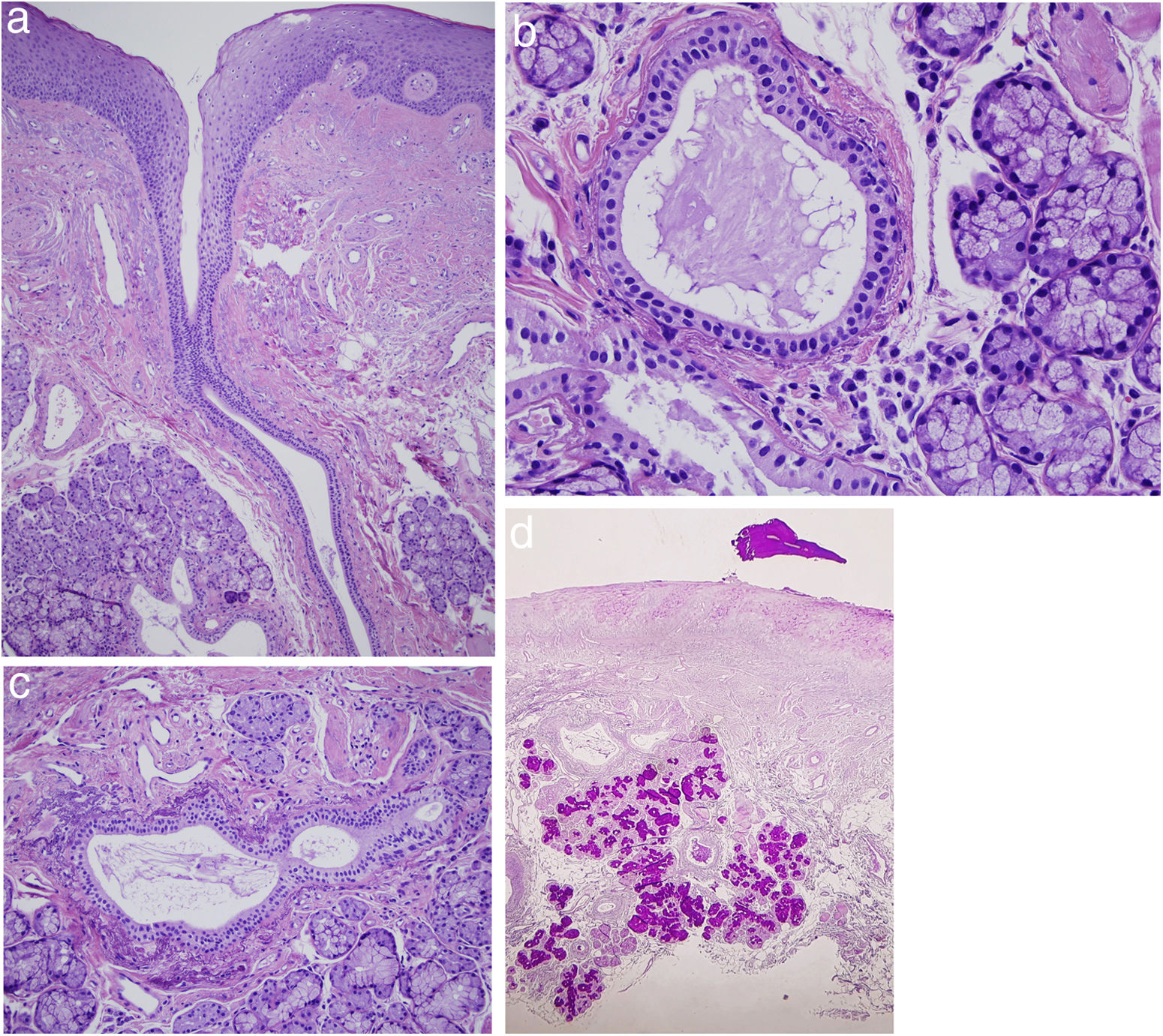

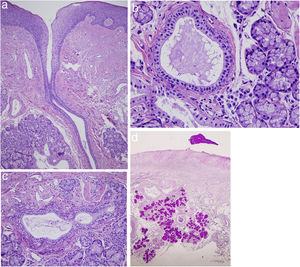

An 80-year-old farmer attended the dermatology-oncology clinic for a regular examination of several cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (pT1) on the face that had been removed some years earlier. He had stopped smoking 25 years before the visit (60 pack-years for 40 years). The physical examination was remarkable not only for leukoplakia and thick scaling of the vermillion border of both lips, but also for the presence of tiny erythematous monomorphic lesions arranged regularly on the mucosa of the lower lip. The patient reported that they had been there for years but were asymptomatic (Fig. 1A). Under gentle pressure, they released a transparent gelatinous material through the ostium (Fig. 1B). Dermoscopy revealed round cup-shaped structures with a more erythematous center and a double vascular pattern comprising fine peripheral hairpin vessels and rosary bead–shaped vessels in the shape of a fingerprint (Fig. 1C). Analysis of a skin biopsy specimen revealed acanthotic mucosa with parakeratotic hyperkeratosis (Fig. 2A) and minor salivary gland tissue with ductal dilatation and squamous metaplasia (Fig. 2B). Abundant plasma cells were observed in the glandular interstitium (CD138+), with absence of light chain restriction, thus ruling out hematologic neoplasia (Fig. 2C). Compact material was visible inside the lumen, extending toward the surface. Periodic acid-Schiff staining was positive (Fig. 2D).

Clinical manifestations. A, Multiple, regularly distributed, and tiny monomorphic erythematous spots on the mucosa of the lower lip. B, Drainage of transparent gelatinous material through the ostia with gentle pressure. C, Dermoscopy showing round, cup-shaped structures with a more erythematous center, and a double vascular pattern comprising fine peripheral hairpin vessels and rosary bead–shaped vessels arranged in the shape of a fingerprint.

Histopathology (hematoxylin–eosin, ×20). A, Minor salivary glands with ductal dilatation. B and C, Squamous metaplasia and plasma cells in the glandular interstitium. D, Compacted material can be seen in the interior of the lumens. This extended to the surface and stained positive for periodic acid-Schiff.

Glandular cheilitis (or cheilitis glandularis) has received little attention in the medical literature. First reported by von Volkman in 1879, it is a chronic, persistent disorder characterized by hyperplasia and inflammation of the salivary glands in the lips and may or may not occur with actinic cheilitis. It mainly affects the lower lip.1 The excretory ducts appear dilated and inflamed and are seen as red and dotted mucosal macules. The volume of the lip may be increased (macrocheilia and eclabium) in deep and suppurative forms (apostematosa), although the simple or superficial form (as we describe here) seems to be more common. The simple variant may be characterized by superficial erosions and crusts, whereas the deep variant may involve scarring. This condition is more common in men, and its etiology is unclear. Associated risk factors include chronic actinic damage, smoking, injury, thick saliva production, bacterial infections, and deficient oral hygiene.2–4

Diagnosis is based on clinical findings, although histopathology, while not specific, can prove extremely useful for identifying end-stage inflamed, hyperplastic, atrophic salivary glands, as well as ductal metaplasia and ectasia. The differential diagnosis includes actinic cheilitis, irritant or allergic contact cheilitis, atopic cheilitis, lichen planus, sarcoidosis, granulomatous cheilitis, and actinic pruritus.5 Treatment is varied and includes observation and photoprotection, antibiotic therapy, cryotherapy, corticosteroids administered topically or as an infiltration, and vermilionectomy, which is the most effective approach in patients with chronic and suppurative forms. Some authors consider this entity to be premalignant and, therefore, that it requires active treatment. Indeed, glandular cheilitis shares some etiologic and pathogenic factors with actinic cheilitis, although this has never been demonstrated.

In the present case, the clinical manifestations and histopathology findings were consistent with glandular cheilitis. The patient was asymptomatic and preferred to avoid invasive treatments. Therefore, we opted for a conservative approach involving the suppression of predisposing factors, rigorous photoprotection, and close monitoring, which, moreover, was necessary owing to the patient's history of skin cancer.1,2 Glandular cheilitis is infrequently reported and probably underdiagnosed, and its dermoscopic characteristics have not been discussed to date. We report a case in which the lesions were very striking. Health professionals should become aware of this condition given its role as an indirect marker of chronic actinic damage of the lip and, therefore, the associated increased risk of neoplasm.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.