Vitiligo is the most common depigmentation disorder, affecting 0.5–1% of the world's population. Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a recently described scarring alopecia that mostly affects postmenopausal women and whose incidence has been increasing gradually during the last decade.

The most widely accepted theory for the pathophysiology of vitiligo is that it is caused by the convergence of genetic factors, autoimmunity, oxidative stress, and neurotoxicity, among others.1 In the case of FFA, the pathogenic model taking shape includes genetic factors, activation of the innate immune system, elimination of epithelial stem cells, activation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and hormonal factors.2 While vitiligo and FFA occur together infrequently, an understanding of the underlying pathophysiological events can provide new clues as to treatment of FFA, which, to date, has been considered a progressive disease that responds poorly to available treatment options.3

Case PresentationWe present the case of a 60-year-old woman with a family history of systemic lupus erythematosus (sister) and a 2-year personal history of depigmented lesions mainly affecting the forehead, eyebrows, and thorax. She also had a 1-year history of alopecia. The dermatology examination revealed achromic macules with involvement of the frontal and temporal areas, eyebrows, and thorax. The lesions on the scalp followed the hairline. Recession of the frontal hairline was observed, with loss of follicular units and scarring accompanied by occasional erythematous papules and perifollicular scaling. Wood lamp examination showed clearly delimited depigmented areas emitting a bright blue-whitish fluorescent light (Figs. 1 and 2).

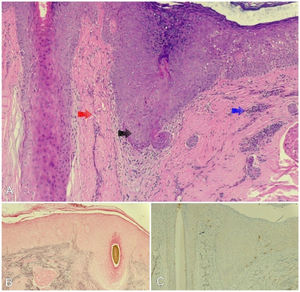

Dermoscopy revealed moderate perifollicular scaling and erythema, with isolated hairs. We performed 2 skin biopsies. Histopathology revealed damage to the basement layer of the hair follicles, with abundant necrotic keratinocytes, in association with lamellar fibrosis, fibrosis in the adjacent dermis, and an inflammatory mononuclear infiltrate in the follicular infundibulum. Staining with Fontana-Masson, S100, and Melan-A was negative for melanocytes (Fig. 3), thus confirming the diagnosis of FFA and vitiligo co-occurring in the same lesion. The Vitiligo Extent Score (VES) was 1.1031 and the Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Severity Score (FFASS) was 11.6.

A, Histopathology revealed vacuolization of the basement layer, abundant necrotic keratinocytes (black arrow), dermal lamellar fibrosis (red arrow), and moderate inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltration (blue arrow). B, Fontana–Masson staining was negative for melanocytes. C, Melan-A immunohistochemical staining was negative for melanocytes.

The patient received treatment with corticosteroids (triamcinolone acetonide, 2mg/mL/mo for 3months), excimer laser (308nm) twice weekly until minimal erythema with a fluence of 550mJ/cm2 was reached (total of 30 sessions), and application of tacrolimus 0.1% ointment twice daily. After 6 months of treatment, repigmentation was visible in some areas, the eczema and inflammation had partly resolved, and new hair follicles had grown, with a VES of 0.665 and an FFASS of 10.1.

DiscussionFFA is a type of scarring alopecia that is characterized by continuous and progressive recession of the frontotemporal hairline and frequent involvement of the eyebrows. It was first described in menopausal White Australian women, although it is increasingly reported in males and persons from other countries and races.4 It is caused by a lymphocytic infiltrate affecting the frontotemporal hairline, thus leading to chronic inflammation of the hair follicle and subsequent scarring alopecia. It has been associated with the influence of hormones during the menopause and many diseases, such as autoimmune disorders (e.g., hypothyroidism and vitiligo).

The literature contains 7 reports of FFA and vitiligo co-occurring at the same site (Table 1), with most cases affecting White patients. Here, we report the case of co-occurrence of both conditions in which the pigmentation disorder preceded alopecia by 1 year. The various hypotheses put forward to explain the pathophysiologic phenomenon include cytotoxic CD8 lymphocyte activity (common to both diseases), Koebner phenomenon (which can lead to FFA at sites previously affected by vitiligo), and the actinic damage caused by exposure of depigmented areas of skin to sunlight.6

Cases of Co-occurrence of Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia and Vitiligo.

| Article | Study type | Sex | Age, y | Race | History of vitiligo | History of autoimmune disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Díaz and Miteva, 20195 | Case study | Female | 57 | Hispanic origin | No | No |

| Katoulis et al., 20168 | Case study | Female | 72 | White | Yes | Hypothyroidism/morphea |

| Male | 48 | White | Yes | No | ||

| Miteva et al., 20117 | Case series | Female | 55 | White | Yes | No |

| Female | 67 | White | Yes | Hypothyroidism | ||

| Female | 67 | White | Yes | Hypothyroidism | ||

| Female | 42 | Hispanic origin | Yes | No | ||

The patient was a constant user of hair dyes, which may have triggered both diseases. Phenol is a common component of depigmenting agents. Its structure is similar to that of tyrosine, thus enabling it to inhibit melanogenesis and generating an inflammatory response, with the subsequent autoimmunity and destruction of melanocytes that is observed in vitiligo. Furthermore, contact with these chemicals can lead to exposure to normally hidden follicular antigens, which can be detected and attacked by the cellular immune system. Prolonged stimulation of the inflammatory response could account for the resulting destruction of the hair follicles in FFA.8 Understanding these immunologic mechanisms could prove useful for the treatment of patients with both diseases. Cohort studies are necessary to calculate the risk of FFA and vitiligo in populations exposed to topical chemical products, such as hair dyes. We think these chemical hair care products should be avoided by patients with vitiligo affecting the hairline of the scalp, although this recommendation should be validated in studies.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.