Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a synthetic lysine analog with antifibrinolytic properties used to reduce bleeding during various surgical procedures. In dermatologic surgery, it is often applied topically (soaked gauze), subcutaneously (intralesional with local anesthesia), and intravenously. We conducted a narrative review on the utility of TXA in dermatologic surgery, both oncologic and esthetic. Therefore, we conducted a literature search across PubMed and Google Scholar during March 2025, including retrospective and prospective studies, and systematic reviews. We eventually found multiple randomized clinical trials demonstrating a reduction in intra- and postoperative bleeding, ecchymosis, and minor hematomas, especially in Mohs surgery, blepharoplasty, and facial rhytidectomy (facelift), and reduced surgical duration during blepharoplasty and rhytidectomy. The safety profile of TXA is highly favorable, with no observed increase in thromboembolic events. However, optimal dosing and routes of administration have yet to be established.

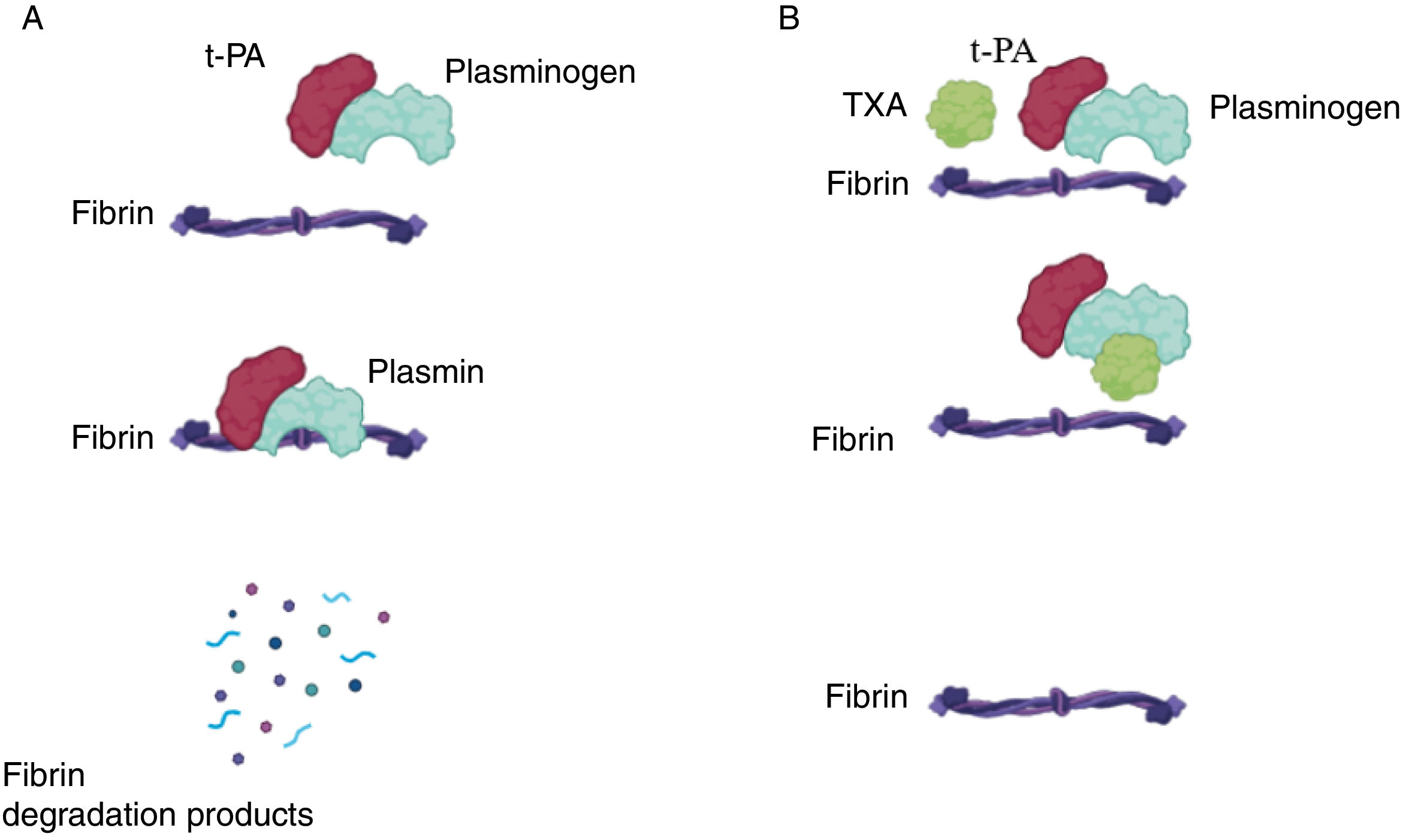

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a synthetic analog of lysine with an antifibrinolytic effect. It blocks the binding sites of plasminogen to fibrin, preventing its conversion to plasmin and stabilizing the fibrin mesh, thereby reducing bleeding (Fig. 1).1 It has been successfully used to reduce hemorrhagic complications in general surgery and gynecology, among other surgical specialties.2,3 Recent studies show that it can reduce bleeding in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS),4,5 in blepharoplasties,6,7 and in facial rhytidectomy (facelift).8,9 TXA has been used in gauze impregnated with the drug,10 subcutaneously (intralesionally)—most often mixed with local anesthetics4—or intravenously prior to surgery.11 Below, we present a review on the effectiveness and safety of TXA in oncologic and esthetic dermatologic surgery.

Mechanism of action of tranexamic acid. (A) Under normal conditions, tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) binds to plasminogen, catalyzing its conversion into plasmin, which in turn degrades fibrin, leading to the breakdown of the hemostatic plug. (B) In the presence of tranexamic acid (TXA), it binds to plasmin, preventing its action on fibrin and promoting hemostasis.

We conducted a narrative review in March 2025 through searches across Medline and Google Scholar using the keywords: “tranexamic acid,” “tranexamic,” “surgery,” “skin cancer,” “dermatology,” “bleeding,” “Mohs surgery,” “blepharoplasty,” “rhytidectomy,” “facelift,” “esthetic surgery,” “plastic surgery.” Articles in Spanish and English were included, encompassing retrospective and prospective studies (>10 patients), clinical trials (CTs), meta-analyses, systematic reviews (SRs), and ongoing CTs listed in clinicaltrials.gov. Articles were screened by title and abstract and selected according to relevance. All 3 authors participated in the search and selection process.

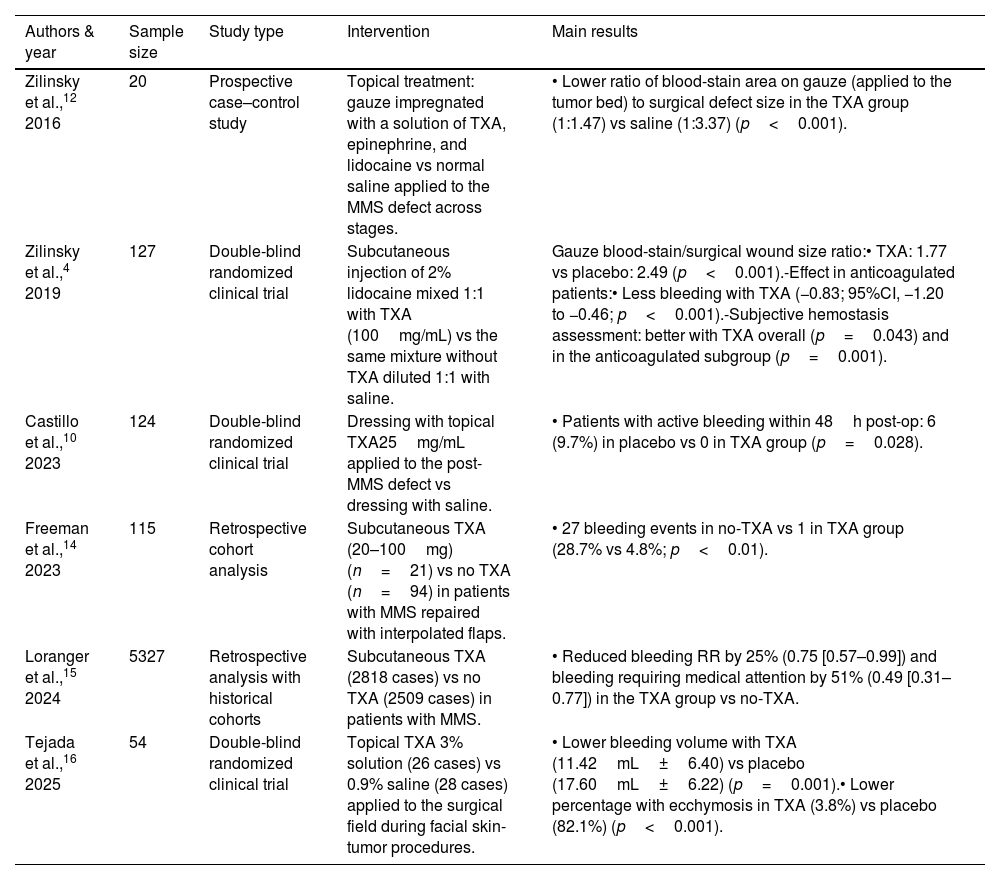

ResultsEffectiveness in oncologic dermatologic surgeryWe found 8 articles on the use of TXA in oncologic dermatologic surgery for skin cancer2,3,8–13 (Table 1), including three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 1 S.5 Most of these studies demonstrated that TXA is safe and effective as a hemostatic adjuvant in MMS.5

Studies evaluating tranexamic acid in oncologic dermatologic surgery.

| Authors & year | Sample size | Study type | Intervention | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zilinsky et al.,12 2016 | 20 | Prospective case–control study | Topical treatment: gauze impregnated with a solution of TXA, epinephrine, and lidocaine vs normal saline applied to the MMS defect across stages. | • Lower ratio of blood-stain area on gauze (applied to the tumor bed) to surgical defect size in the TXA group (1:1.47) vs saline (1:3.37) (p<0.001). |

| Zilinsky et al.,4 2019 | 127 | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | Subcutaneous injection of 2% lidocaine mixed 1:1 with TXA (100mg/mL) vs the same mixture without TXA diluted 1:1 with saline. | Gauze blood-stain/surgical wound size ratio:• TXA: 1.77 vs placebo: 2.49 (p<0.001).-Effect in anticoagulated patients:• Less bleeding with TXA (−0.83; 95%CI, −1.20 to −0.46; p<0.001).-Subjective hemostasis assessment: better with TXA overall (p=0.043) and in the anticoagulated subgroup (p=0.001). |

| Castillo et al.,10 2023 | 124 | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | Dressing with topical TXA25mg/mL applied to the post-MMS defect vs dressing with saline. | • Patients with active bleeding within 48h post-op: 6 (9.7%) in placebo vs 0 in TXA group (p=0.028). |

| Freeman et al.,14 2023 | 115 | Retrospective cohort analysis | Subcutaneous TXA (20–100mg) (n=21) vs no TXA (n=94) in patients with MMS repaired with interpolated flaps. | • 27 bleeding events in no-TXA vs 1 in TXA group (28.7% vs 4.8%; p<0.01). |

| Loranger et al.,15 2024 | 5327 | Retrospective analysis with historical cohorts | Subcutaneous TXA (2818 cases) vs no TXA (2509 cases) in patients with MMS. | • Reduced bleeding RR by 25% (0.75 [0.57–0.99]) and bleeding requiring medical attention by 51% (0.49 [0.31–0.77]) in the TXA group vs no-TXA. |

| Tejada et al.,16 2025 | 54 | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | Topical TXA 3% solution (26 cases) vs 0.9% saline (28 cases) applied to the surgical field during facial skin-tumor procedures. | • Lower bleeding volume with TXA (11.42mL±6.40) vs placebo (17.60mL±6.22) (p=0.001).• Lower percentage with ecchymosis in TXA (3.8%) vs placebo (82.1%) (p<0.001). |

TXA: tranexamic acid; MMS: Mohs micrographic surgery; RCT: randomized clinical trial; CI: confidence interval; IV: intravenous.

A double-blind RCT10 compared topical TXA 25mg/mL applied with a dressing to saline in 124 patients undergoing MMS. No TXA-treated patients experienced active bleeding within 48h postoperatively vs 6 from the control group (p=0.028). Due to the small sample size, the subgroup of anticoagulated patients could not be analyzed. Another RCT (n=54)16 showed reduced bleeding (11.42mL±6.40 vs 17.60mL±6.22, p=0.001) and a lower rate of ecchymosis (3.8% vs 82.1%; p<0.001) with 3% topical TXA vs control. Patients on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy were excluded. Finally, a case-control study (n=40)12 observed a lower ratio between the blood-stain area on the gauze (applied over the tumor bed) and the size of the surgical defect in the treated group (1:1.47 vs 1:3.37; p<0.001).

Subcutaneous (intralesional) injection of tranexamic acidA double-blind RCT4 with 127 patients undergoing MMS compared subcutaneous (intralesional) injection of TXA 100mg/mL mixed with local anesthesia vs anesthesia alone. The ratio between the blood-stain area and the defect size was significantly lower with TXA (1:1.77 vs 1:2.49; p<0.001). Additionally, anticoagulated patients exhibited less bleeding (mean difference [MD] −0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −1.20 to −0.46; p<0.001) and better subjective hemostasis assessments (p=0.043 overall; p=0.001 in anticoagulated patients).

A large retrospective study15 (n=5327) in patients with MMS showed a significant 25% relative risk (RR) reduction in bleeding (0.75 [0.57–0.99]) and a 51% reduction for bleeding requiring medical attention (0.49 [0.31–0.77]) in the TXA-treated group (n=2818). This reduction was also significant among patients using antiplatelet or direct-acting oral anticoagulants, but not in anticoagulated patients overall. No increased rate of thromboembolic events was observed. Another retrospective study14 (n=115) on MMS with interpolated flaps (e.g., paramedian forehead or melolabial) found only 1 bleed in the TXA group vs 27 in the non-TXA group (4.8% vs 28.7%; p<0.01).

Currently, an RCT (NCT06057675) is recruiting to evaluate subcutaneous TXA 100mg/mL vs local anesthesia alone for nasal reconstruction after MMS.

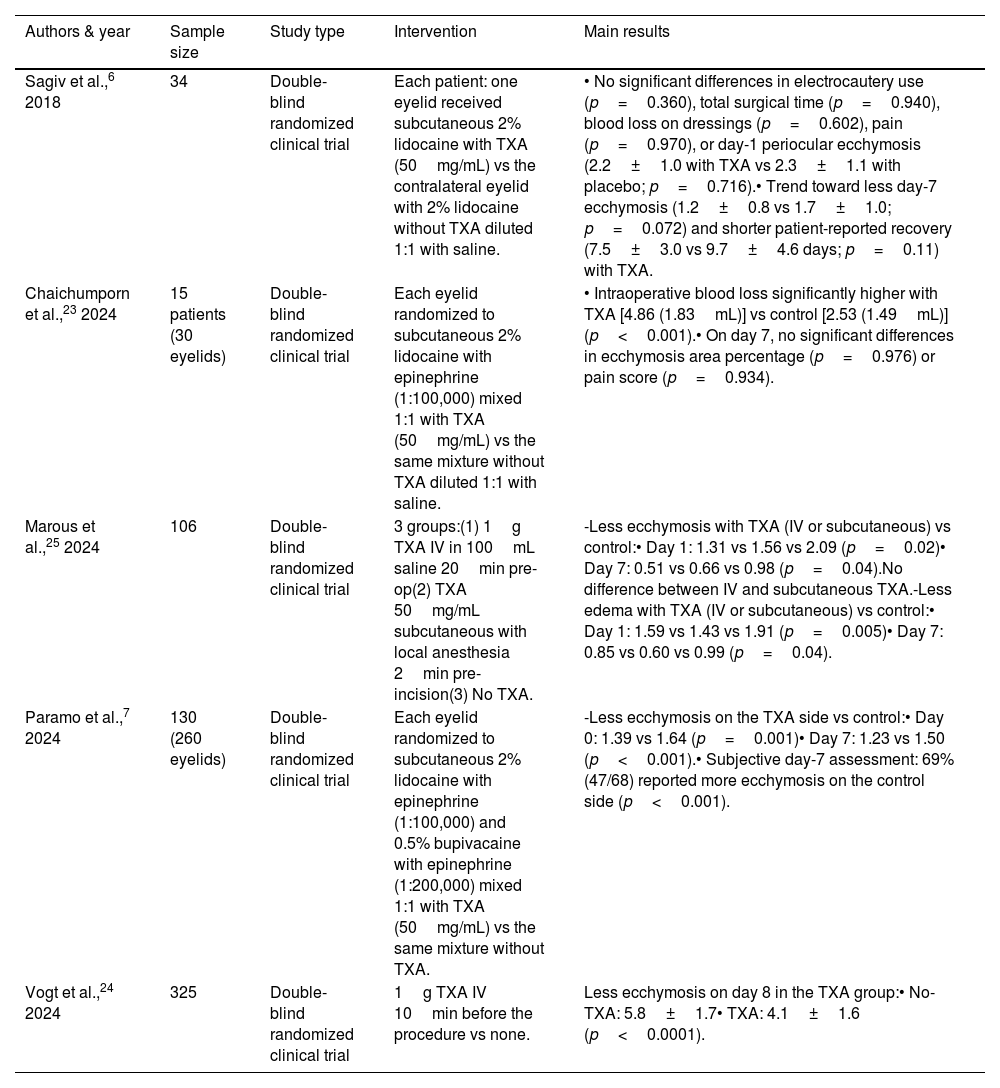

Effectiveness in blepharoplasty (Table 2)Ahmed et al.17 (2024) reviewed meta-analyses and SRs on TXA use in rhinoplasty, septorhinoplasty, and blepharoplasty. For the latter, they included 6 SRs18–22—the most recent from 202322—covering 44–243 patients (each SR included 1–5 studies). Three SRs showed lower bleeding volume with TXA vs placebo, with similar results across topical, intralesional, and systemic routes. Five SRs reported reduced drainage volume and a trend toward less ecchymosis and edema. No significant differences were found in postoperative hematoma rates. One meta-analysis22 including 6 studies found a significant reduction in hemorrhage risk (−1.05; 95%CI, −1.72 to −0.38), though only 1 study6 focused on blepharoplasty.

Studies evaluating tranexamic acid in blepharoplasty.

| Authors & year | Sample size | Study type | Intervention | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sagiv et al.,6 2018 | 34 | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | Each patient: one eyelid received subcutaneous 2% lidocaine with TXA (50mg/mL) vs the contralateral eyelid with 2% lidocaine without TXA diluted 1:1 with saline. | • No significant differences in electrocautery use (p=0.360), total surgical time (p=0.940), blood loss on dressings (p=0.602), pain (p=0.970), or day-1 periocular ecchymosis (2.2±1.0 with TXA vs 2.3±1.1 with placebo; p=0.716).• Trend toward less day-7 ecchymosis (1.2±0.8 vs 1.7±1.0; p=0.072) and shorter patient-reported recovery (7.5±3.0 vs 9.7±4.6 days; p=0.11) with TXA. |

| Chaichumporn et al.,23 2024 | 15 patients (30 eyelids) | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | Each eyelid randomized to subcutaneous 2% lidocaine with epinephrine (1:100,000) mixed 1:1 with TXA (50mg/mL) vs the same mixture without TXA diluted 1:1 with saline. | • Intraoperative blood loss significantly higher with TXA [4.86 (1.83mL)] vs control [2.53 (1.49mL)] (p<0.001).• On day 7, no significant differences in ecchymosis area percentage (p=0.976) or pain score (p=0.934). |

| Marous et al.,25 2024 | 106 | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | 3 groups:(1) 1g TXA IV in 100mL saline 20min pre-op(2) TXA 50mg/mL subcutaneous with local anesthesia 2min pre-incision(3) No TXA. | -Less ecchymosis with TXA (IV or subcutaneous) vs control:• Day 1: 1.31 vs 1.56 vs 2.09 (p=0.02)• Day 7: 0.51 vs 0.66 vs 0.98 (p=0.04).No difference between IV and subcutaneous TXA.-Less edema with TXA (IV or subcutaneous) vs control:• Day 1: 1.59 vs 1.43 vs 1.91 (p=0.005)• Day 7: 0.85 vs 0.60 vs 0.99 (p=0.04). |

| Paramo et al.,7 2024 | 130 (260 eyelids) | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | Each eyelid randomized to subcutaneous 2% lidocaine with epinephrine (1:100,000) and 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine (1:200,000) mixed 1:1 with TXA (50mg/mL) vs the same mixture without TXA. | -Less ecchymosis on the TXA side vs control:• Day 0: 1.39 vs 1.64 (p=0.001)• Day 7: 1.23 vs 1.50 (p<0.001).• Subjective day-7 assessment: 69% (47/68) reported more ecchymosis on the control side (p<0.001). |

| Vogt et al.,24 2024 | 325 | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | 1g TXA IV 10min before the procedure vs none. | Less ecchymosis on day 8 in the TXA group:• No-TXA: 5.8±1.7• TXA: 4.1±1.6 (p<0.0001). |

TXA: tranexamic acid; RCT: randomized clinical trial; CI: confidence interval; IV: intravenous.

Recently, new RCTs with larger sample sizes, not included in these systematic reviews, have been published:

Subcutaneous (intralesional) injection of tranexamic acidA double-blind RCT7 (n=130) in which each eyelid received TXA 50mg/mL (with lidocaine, bupivacaine, and adrenaline) on one side and no TXA on the other, found less ecchymosis in the treated side on day 0 (score 1.39 vs 1.64; p=0.001) and day 7 (score 1.23 vs 1.50; p<0.001), and lower patient-reported bruising at day 7 (25% vs 69%; p<0.001). Another smaller RCT23 (n=15) using a similar design showed greater bleeding with TXA, though ecchymosis did not differ at 7 days.

IV infusion of tranexamic acidA recent RCT24 (n=325) compared 1g IV TXA 10min before surgery vs none, observing lower ecchymosis scores at day 8 (4.1±1.6 vs 5.8±1.7; p<0.0001). Another RCT25 (n=106) compared IV TXA (1g 20min pre-op) and subcutaneous TXA (50mg/mL intralesional) vs control (lidocaine with adrenaline), finding lower ecchymosis and edema scores in both TXA groups.

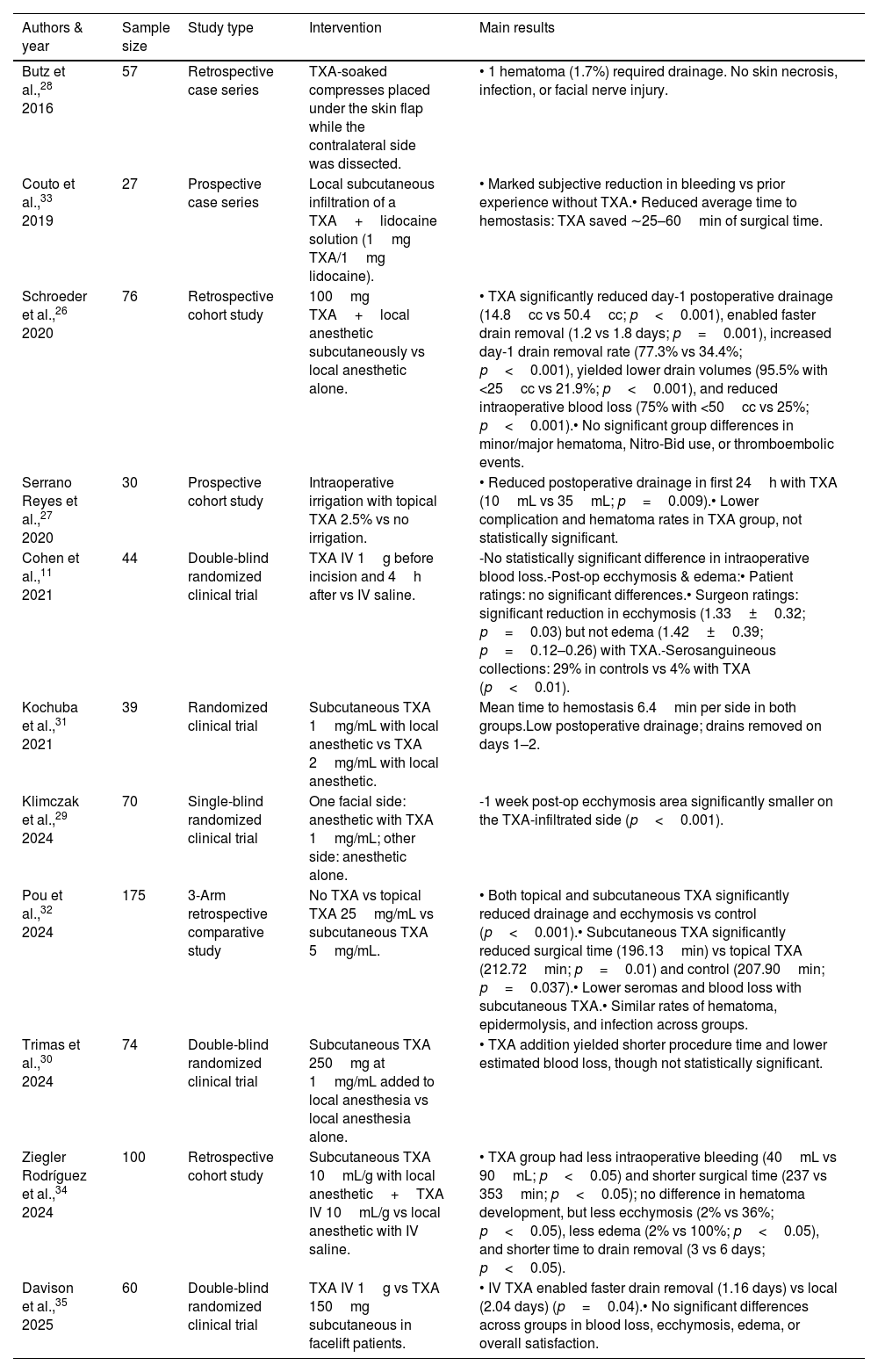

Effectiveness in facial rhytidectomy (facelift) (Table 3)Al-Hashimi et al.8 (2023) published an SR including 3 studies11,26,27 with different administration routes, concluding that due to heterogeneity in dose and technique, the efficacy of TXA in rhytidectomy remained debatable. More recently, Alenazi et al.9 (2024) published an SR of 7 studies (388 patients) with various TXA routes, concluding that TXA significantly reduced postoperative drainage and minor hematomas without increasing major complications. We analyze the main studies below.

Studies evaluating tranexamic acid in facial rhytidectomy (facelift).

| Authors & year | Sample size | Study type | Intervention | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butz et al.,28 2016 | 57 | Retrospective case series | TXA-soaked compresses placed under the skin flap while the contralateral side was dissected. | • 1 hematoma (1.7%) required drainage. No skin necrosis, infection, or facial nerve injury. |

| Couto et al.,33 2019 | 27 | Prospective case series | Local subcutaneous infiltration of a TXA+lidocaine solution (1mg TXA/1mg lidocaine). | • Marked subjective reduction in bleeding vs prior experience without TXA.• Reduced average time to hemostasis: TXA saved ∼25–60min of surgical time. |

| Schroeder et al.,26 2020 | 76 | Retrospective cohort study | 100mg TXA+local anesthetic subcutaneously vs local anesthetic alone. | • TXA significantly reduced day-1 postoperative drainage (14.8cc vs 50.4cc; p<0.001), enabled faster drain removal (1.2 vs 1.8 days; p=0.001), increased day-1 drain removal rate (77.3% vs 34.4%; p<0.001), yielded lower drain volumes (95.5% with <25cc vs 21.9%; p<0.001), and reduced intraoperative blood loss (75% with <50cc vs 25%; p<0.001).• No significant group differences in minor/major hematoma, Nitro-Bid use, or thromboembolic events. |

| Serrano Reyes et al.,27 2020 | 30 | Prospective cohort study | Intraoperative irrigation with topical TXA 2.5% vs no irrigation. | • Reduced postoperative drainage in first 24h with TXA (10mL vs 35mL; p=0.009).• Lower complication and hematoma rates in TXA group, not statistically significant. |

| Cohen et al.,11 2021 | 44 | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | TXA IV 1g before incision and 4h after vs IV saline. | -No statistically significant difference in intraoperative blood loss.-Post-op ecchymosis & edema:• Patient ratings: no significant differences.• Surgeon ratings: significant reduction in ecchymosis (1.33±0.32; p=0.03) but not edema (1.42±0.39; p=0.12–0.26) with TXA.-Serosanguineous collections: 29% in controls vs 4% with TXA (p<0.01). |

| Kochuba et al.,31 2021 | 39 | Randomized clinical trial | Subcutaneous TXA 1mg/mL with local anesthetic vs TXA 2mg/mL with local anesthetic. | Mean time to hemostasis 6.4min per side in both groups.Low postoperative drainage; drains removed on days 1–2. |

| Klimczak et al.,29 2024 | 70 | Single-blind randomized clinical trial | One facial side: anesthetic with TXA 1mg/mL; other side: anesthetic alone. | -1 week post-op ecchymosis area significantly smaller on the TXA-infiltrated side (p<0.001). |

| Pou et al.,32 2024 | 175 | 3-Arm retrospective comparative study | No TXA vs topical TXA 25mg/mL vs subcutaneous TXA 5mg/mL. | • Both topical and subcutaneous TXA significantly reduced drainage and ecchymosis vs control (p<0.001).• Subcutaneous TXA significantly reduced surgical time (196.13min) vs topical TXA (212.72min; p=0.01) and control (207.90min; p=0.037).• Lower seromas and blood loss with subcutaneous TXA.• Similar rates of hematoma, epidermolysis, and infection across groups. |

| Trimas et al.,30 2024 | 74 | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | Subcutaneous TXA 250mg at 1mg/mL added to local anesthesia vs local anesthesia alone. | • TXA addition yielded shorter procedure time and lower estimated blood loss, though not statistically significant. |

| Ziegler Rodríguez et al.,34 2024 | 100 | Retrospective cohort study | Subcutaneous TXA 10mL/g with local anesthetic+TXA IV 10mL/g vs local anesthetic with IV saline. | • TXA group had less intraoperative bleeding (40mL vs 90mL; p<0.05) and shorter surgical time (237 vs 353min; p<0.05); no difference in hematoma development, but less ecchymosis (2% vs 36%; p<0.05), less edema (2% vs 100%; p<0.05), and shorter time to drain removal (3 vs 6 days; p<0.05). |

| Davison et al.,35 2025 | 60 | Double-blind randomized clinical trial | TXA IV 1g vs TXA 150mg subcutaneous in facelift patients. | • IV TXA enabled faster drain removal (1.16 days) vs local (2.04 days) (p=0.04).• No significant differences across groups in blood loss, ecchymosis, edema, or overall satisfaction. |

TXA: tranexamic acid; RCT: randomized clinical trial; CI: confidence interval; IV: intravenous.

Serrano Reyes et al.27 prospectively compared intraoperative irrigation with 2.5% TXA in 15 patients vs no irrigation in 15 controls, finding reduced drainage within the first 24h (10mL vs 35mL; p=0.009). A retrospective study (n=57)28 used TXA-soaked compresses placed beneath the skin flap while the contralateral side was being dissected, repeating the process on the opposite side while the first was being closed. Only 1 hematoma requiring drainage was observed, with no relevant complications.

Subcutaneous (intralesional) injection of tranexamic acidKlimczak et al.29 published in 2024 a double-blind randomized clinical trial in which 70 patients received subcutaneous TXA 1mg/mL mixed with local anesthetic on one side of the face, while the other side received anesthetic alone. One week after the procedure, the area of ecchymosis was significantly smaller on the TXA-treated side (20.8±10.2 vs 28.5±12.1; p<0.001). Another similar RCT (n=74)30 showed a reduction in surgical time and blood loss with TXA, although the difference did not reach statistical significance. Regarding dosage, Kochuba et al.31 compared TXA 1mg/mL vs 2mg/mL on opposite sides of the face in an RCT (n=39) and found no differences in time to hemostasis or postoperative drainage.

Regarding comparative studies between administration routes, Pou et al.32 conducted a retrospective study (n=175) evaluating three groups: no TXA, topical TXA 25mg/mL, and subcutaneous/intralesional TXA 5mg/mL. Both TXA administration routes reduced drainage and ecchymosis, with the subcutaneous route being superior in reducing surgical time, seroma formation, and blood loss. Other retrospective studies and case series have reported similar results.26,33 Currently, an ongoing RCT (NCT06345833) is comparing subcutaneous (intralesional) TXA 1%, topical TXA 3%, and their combination.

IV infusion of tranexamic acidA double-blind RCT (n=44)11 using TXA 1g IV administered before and 4hours after incision vs placebo found a significant reduction in ecchymosis rated by the surgeon (1.33±0.32 vs 1.63±0.55; p=0.03) and fewer serosanguineous collections (1 vs 5; p<0.01). A retrospective study analyzed 100 patients treated with TXA 10mg/mL IV plus 10mL/g subcutaneous (intralesional) TXA vs a no-TXA group, showing less intraoperative bleeding, shorter surgical time, and reduced ecchymosis, edema, and drain removal time in the TXA-treated groups.34

Regarding comparative studies, a very recent double-blind RCT (n=60)35 compared TXA 1g IV vs TXA 150mg subcutaneous (intralesional) and reported a shorter time to drain removal only in the IV group (1.16 vs 2.04 days; p=0.04).

Effectiveness in other dermatologic surgical proceduresA retrospective case–control study13 with 40 patients undergoing lipoma excision reported a significantly lower ecchymosis score at the first postoperative visit in the TXA-treated group (which received 500mg orally every 12h within the first 5 days after surgery) vs controls. No differences were observed in postoperative edema.

Safety profile of tranexamic acidThe use of TXA in dermatologic surgery shows a very low rate of adverse events (AEs).5,18 Some patients may experience dizziness, headache, nausea, or abdominal pain. No increase in the risk of cardiopulmonary or cerebrovascular thromboembolic events has been observed in association with its use.17

DiscussionEvidence on the effectiveness and safety of TXA in surgery is well established.36 Clinical trials have shown reduced mortality from postpartum and major traumatic bleeding without increasing thromboembolic risk.37,38 In a survey of 502 U.S. plastic surgeons, 90% reported using TXA in esthetic surgery (83.6% in facelifts), and 92% had not observed AEs.39 However, its application in dermatologic surgery is only recently being explored.5 Major hemorrhages requiring medical attention after dermatologic surgery are exceedingly rare, and severe events with long-term complications are even less common—making TXA use in this context debatable. Most TXA studies in dermatologic surgery involve cosmetic procedures, where reducing ecchymosis is more relevant given patient expectations.

In blepharoplasty, TXA may reduce intraoperative bleeding and postoperative ecchymosis, among other parameters.18–22 Regarding facelift (rhytidectomy), the most widely used routes of administration are IV and subcutaneous (intralesional). Its main benefits include a reduction in surgical time, intraoperative bleeding, ecchymosis, and minor hematomas. However, it does not appear to reduce larger hematomas.9

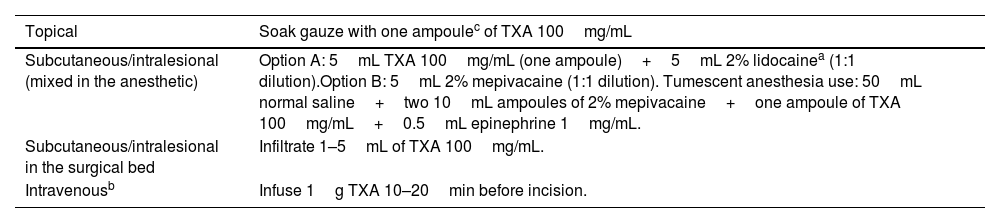

In dermatologic oncologic surgery (such as Mohs micrographic surgery, MMS), TXA may decrease the incidence of ecchymosis, hematoma, and postoperative edema, improve overall patient satisfaction, and reduce by half the rate of postoperative bleeding events requiring medical attention.15 This may be particularly relevant in patients using antithrombotic agents or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).15 In addition, in more complex surgical procedures, TXA may reduce surgical time (although no studies have specifically evaluated this in MMS). Despite several RCTs supporting the efficacy of TXA,4,10,16 there are currently no standardized guidelines or protocols for its use in dermatologic oncologic surgery—likely due to the recency of studies and the heterogeneity in administration routes and dosages reported in the literature.5 Indeed, no studies have evaluated IV TXA use in dermatologic oncologic surgery, unlike in blepharoplasty and facelift. Furthermore, although there are at least 3 RCTs published on dermatologic oncologic surgery, 5 in blepharoplasty, and 5 in facelift (Tables 1–3), methodologies are often heterogeneous, as are the outcome measures used to assess drug effectiveness, and in several studies, it remains uncertain whether the reduction in bleeding is clinically meaningful. In our clinical practice, we usually employ TXA in patients at high risk of bleeding (due to either patient characteristics or surgical complexity), using it by soaking gauze pads, injecting intralesionally into the surgical bed, or as part of tumescent anesthesia (Table 4).

Ways to use tranexamic acid in dermatologic surgery.

| Topical | Soak gauze with one ampoulec of TXA 100mg/mL |

|---|---|

| Subcutaneous/intralesional (mixed in the anesthetic) | Option A: 5mL TXA 100mg/mL (one ampoule)+5mL 2% lidocainea (1:1 dilution).Option B: 5mL 2% mepivacaine (1:1 dilution). Tumescent anesthesia use: 50mL normal saline+two 10mL ampoules of 2% mepivacaine+one ampoule of TXA 100mg/mL+0.5mL epinephrine 1mg/mL. |

| Subcutaneous/intralesional in the surgical bed | Infiltrate 1–5mL of TXA 100mg/mL. |

| Intravenousb | Infuse 1g TXA 10–20min before incision. |

TXA: tranexamic acid; g: gram; mg: milligram; mL: milliliter.

Regarding its use in anticoagulated patients or those taking antiplatelet agents, there is evidence supporting the usefulness of TXA.40–42 In MMS, it appears to reduce hemorrhagic risk, as demonstrated in subgroup analyses from several studies.4,15 In the case of blepharoplasty and facelift, such patients are usually excluded from trials, so no evidence is currently available.

Concerning its safety profile, TXA is well tolerated across all routes of administration (topical, intralesional, and systemic), with no observed increase in serious adverse events such as cardiopulmonary or cerebrovascular thromboembolism.43

With regard to cost, TXA is inexpensive in the hospital setting within the Spanish National Health System—in our center, a 500mg vial costs €0.32—thus, cost would not be a limiting factor for its use.

LimitationsThis review is limited by its narrative design—it is neither a systematic review nor a meta-analysis. Few studies evaluate TXA use in oncologic dermatologic surgery, and no consensus exists on optimal route or dosage. Similarly, there is no universally accepted method to assess surgical bleeding or postoperative hemorrhage.

ConclusionsTXA is a safe drug for dermatologic surgery, with no observed increase in cardioembolic risk. It may reduce intra- and postoperative bleeding complications and surgical time in complex procedures such as facial rhytidectomy and blepharoplasty. However, optimal dosage, route, and patient selection remain undefined, given the low baseline hemorrhagic complication rate in dermatologic surgery. Further studies are needed to evaluate its use in both MMS and esthetic procedures, directly comparing TXA dosages and administration routes.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.