Psoriatic arthritis, a chronic inflammatory musculoskeletal disease that is associated with psoriasis, causes joint erosions, accompanied by loss of function and quality-of-life. The clinical presentation is variable, with extreme phenotypes that can mimic rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. Because psoriasis usually presents before psoriatic arthritis, the dermatologist plays a key role in early detection of the latter. As many treatments used in psoriasis are also used in psoriatic arthritis, treatment recommendations should take into consideration the type and severity of both conditions. This consensus paper presents guidelines for the coordinated management of psoriatic arthritis by rheumatologists and dermatologists. The paper was drafted by a multidisciplinary group (6rheumatologists, 6dermatologists, and 2epidemiologists) using the Delphi method and contains recommendations, tables, and algorithms for the diagnosis, referral, and treatment of patients with psoriatic arthritis.

La artritis psoriásica es una enfermedad inflamatoria crónica que afecta al sistema musculoesquelético, se asocia a psoriasis y suele producir destrucción articular con pérdida de función y calidad de vida. Su presentación clínica es heterogénea, con extremos fenotípicos que pueden solaparse con la artritis reumatoide o la espondilitis anquilosante. La psoriasis suele preceder a la artritis psoriásica, y la consulta de dermatología es el lugar clave para su detección precoz. Muchos tratamientos utilizados en psoriasis también se utilizan en artritis psoriásica, por tanto las recomendaciones terapéuticas para la psoriasis deben realizarse teniendo en cuenta el tipo y la gravedad de la artritis psoriásica, y viceversa. El objetivo de este documento es establecer pautas para el manejo coordinado (reumatólogo/dermatólogo) de la artritis psoriásica. Ha sido elaborado mediante la técnica Delphi por un grupo multidisciplinar (6reumatólogos, 6dermatólogos y 2epidemiólogos) y contiene recomendaciones, tablas y algoritmos para diagnóstico, criterios de derivación y tratamiento de la artritis psoriásica.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory musculoskeletal disorder associated with psoriasis. The prevalence of psoriasis in the general population ranges from 0.1% to 2.8%1 and between 6% and 42% of these patients also have arthritis.2 In approximately 70% of cases, cutaneous symptoms precede the onset of joint disease, musculoskeletal symptoms precede skin disease in only 15% of cases, and both occur simultaneously in 15%.3 The risk of PsA remains constant following initial diagnosis of psoriasis, and the prevalence reaches 20.5% after 30years.4 It has been estimated that the mean (SD) interval between the diagnosis of psoriasis and the onset of PsA is 17 (11)years.5

PsA was initially considered to be a milder disorder than rheumatoid arthritis, but its progressive course was subsequently shown to cause joint damage and loss of function comparable to that of rheumatoid arthritis.6 Its clinical expression is very variable, and the disease can manifest as spondyloarthritis, peripheral arthritis, dactylitis, and enthesitis.7 The most common presentation is oligoarticular peripheral arthritis, followed by the symmetric polyarticular variant, which is similar to the typical presentation of rheumatoid arthritis. The pure axial form, similar to ankylosing spondylitis, is much less common. Between 20% and 30% of patients develop both axial (sacroiliitis, spondylitis) and peripheral (arthritis) symptoms.8 During the course of the disease, involvement may progress from oligoarticular to polyarticular disease and vice versa.

Moll and Wright9 in 1973 were the first authors to consider PsA to be a separate clinical entity distinct from other rheumatologic diseases. They defined it as a rheumatoid-factor negative inflammatory arthritis associated with psoriasis. In 2006, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) developed the CASPAR criteria (ClASsification criteria for Psoriatic ARthritis).10 One of the main advantages of this instrument is that it can be used to diagnose PsA in patients who do not have psoriasis and in patients with a positive rheumatoid factor. This characteristic, and the fact that it is quick and simple to apply, has made CASPAR the most widely used criteria for establishing a diagnosis of PsA.11

Owing to the association of PsA with psoriasis and the fact that, in most cases, joint involvement is preceded by skin disease, the dermatology consultation plays a key role in the early detection of PsA. However, the statistics reveal a somewhat depressing picture. A recent study showed that almost 30% of patients with psoriasis receiving dermatological treatment had undiagnosed PsA.12 Thus, early diagnosis of PsA and prompt referral to a rheumatologist for treatment still represent a real challenge for dermatologists and there is evidence that prompt treatment of PsA can slow the progression of joint damage and the number of joints affected.13

Psoriatic onychopathy is a clinical predictor of PsA which has classically been associated with arthritis (80%-90% in PsA compared to 40%-50% in patients without arthritis).14 Furthermore, although no correlation has been observed between the severity of psoriasis and PsA, an association has been found between the severity of psoriasis and the possibility of developing PsA.12 The scalp, the retroauricular area, and the intergluteal cleft are the sites of psoriasis most often associated with PsA. An association has also been reported between obesity and the development of PsA.15–17

The diagnosis of PsA can be difficult in the dermatological consultation since, in addition to requiring close examination of the entheses, joints, and spine, it also requires imaging studies that are difficult to evaluate in this setting. However, assessment by a rheumatologist of all patients with psoriasis is not a viable option. The solution, therefore, is for the dermatologist to suspect a diagnosis of joint disease on the basis of a physical examination and the patient's medical history. A number of screening questionnaires have been developed to aid the clinician in establishing a suspected diagnosis of PsA in patients with psoriasis: the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation (PASE),18 the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST),19 the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS),20 the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Questionnaire (PASQ),21 and the Early ARthritis for Psoriatic patients (EARP) questionnaire.22 However, the sensitivity and specificity of these instruments is well under 50% when the polyarticular forms of arthritis are excluded,12 and no Spanish versions of these tools have yet been validated. Recent practical guidelines on the management of comorbidity in patients with psoriasis23,24 recommended the use of a simplified version of the CASPAR criteria adapted to the dermatological setting as a tool for diagnosing suspected PsA.10 Patients with suspected PsA should be referred to a rheumatologist for confirmation of the diagnosis.

Clinical management of psoriasis and PsA should be coordinated because most of the systemic treatments used to treat psoriasis, such as disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologic therapy, are also used to treat PsA. Treatment recommendations should be made taking into consideration the type and severity of both conditions. The aim of this consensus document is to establish guidelines and criteria for the coordinated management of PsA by rheumatologists and dermatologists based on the recommendations of the clinical guidelines most widely used in Spain at this time23–32.

ObjectivesGeneral AimsTo establish a set of eminently practical recommendations on the management of PsA for both rheumatologists and dermatologists.

Specific Aims- 1.

To review the tools for screening, assessment, and classification of PsA recommended in the main guidelines and to indicate those most appropriate for each specialty (rheumatology and dermatology) and clinical situation.

- 2.

To develop diagnostic and treatment algorithms for the coordinated management of PsA by dermatologists and rheumatologists.

- 3.

To establish guidelines and recommendations for the coordinated management of PsA.

A working group was set up comprising 12 clinical experts (6rheumatologists and 6dermatologists) and 2epidemiologists with specific experience in developing clinical guidelines and consensus statements. The initiative was started by the 2principal researchers (LP, dermatologist and JDC, rheumatologist), who each invited other physicians from their specialty who had appropriate experience and expertise in the subject to join the panel. Recently published recommendations on the management of PsA were reviewed.23–32 These were identified in a nonsystematic way by the panelists. First drafts of the algorithms and the information on tools for the assessment, prognostic evaluation, and treatment of PsA were drawn up using as a starting point the consensus statement of the Sociedad Española de Reumatología (SER) on the use of biologic agents in the treatment of PsA and the consensus document on an integrated approach to comorbidity in patients with psoriasis published by the Working Group on Comorbidity in Psoriasis of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV).23,24,29 These were then complemented by recommendations taken from the other documents reviewed, especially when the initial information was ambiguous or insufficiently precise. The group of clinical experts directed and supervised all the phases of the study and participated in the formulation of the criteria based on expert opinion (those for which the published evidence was insufficient) and in the establishment of recommendations for the coordinated management of PsA.

The first draft of the document was submitted to the expert panel using the RAND/UCLA method (a modified Delphi process) and the panelists voted on the proposed recommendations using a scale of 1 to 9 (1=totally disagree, 9=totally agree). The recommendations to which more than 70% of the panelists assigned a score of 7 or higher were automatically included in the final document. The recommendations for which consensus (rate of agreement ≥70%) was not achieved were reformulated and submitted to the panel for scoring in the second round of the process. If consensus was not achieved on the second round, the recommendation was deleted from the document.

Each one of the new recommendations developed by the expert panel includes a level of evidence rating, a grade of recommendation based on the system developed by the Centre for Evidenced-Based Medicine at the University of Oxford, and the rate of agreement, that is, the percentage of experts who assigned a score of 7 or higher.33

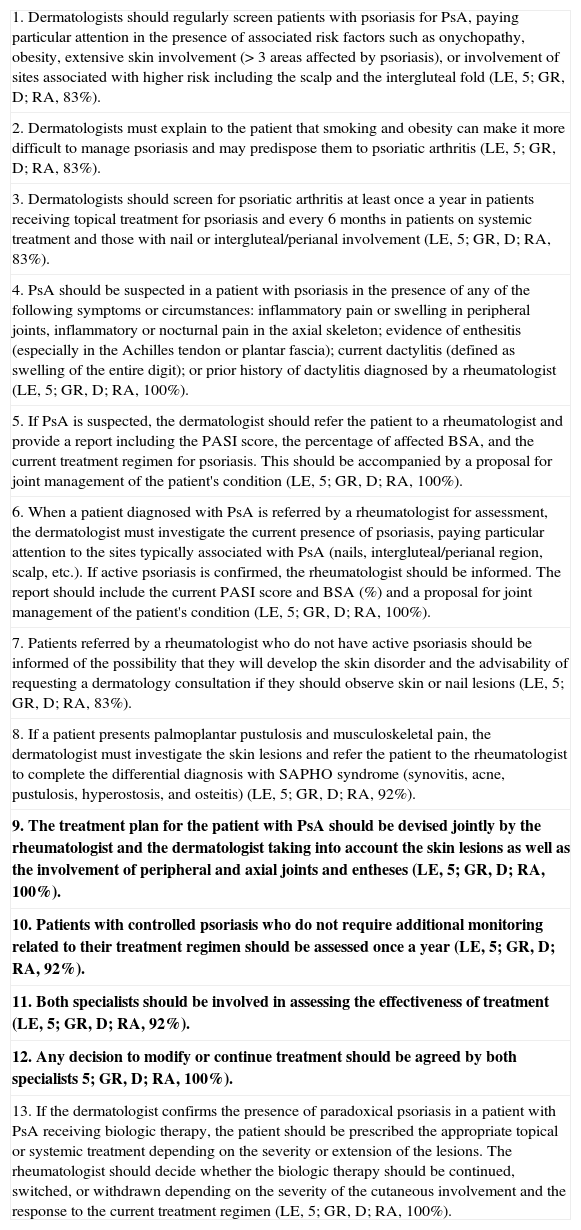

ResultsTables 1 and 2 summarize the recommendations of the panel for screening, treatment, and coordinated follow-up of patients with PsA. Table 1 shows the recommendations for dermatologists and Table 2 the recommendations for rheumatologists.

Recommendations for Dermatologistsa

| 1. Dermatologists should regularly screen patients with psoriasis for PsA, paying particular attention in the presence of associated risk factors such as onychopathy, obesity, extensive skin involvement (>3areas affected by psoriasis), or involvement of sites associated with higher risk including the scalp and the intergluteal fold (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 83%). |

| 2. Dermatologists must explain to the patient that smoking and obesity can make it more difficult to manage psoriasis and may predispose them to psoriatic arthritis (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 83%). |

| 3. Dermatologists should screen for psoriatic arthritis at least once a year in patients receiving topical treatment for psoriasis and every 6months in patients on systemic treatment and those with nail or intergluteal/perianal involvement (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 83%). |

| 4. PsA should be suspected in a patient with psoriasis in the presence of any of the following symptoms or circumstances: inflammatory pain or swelling in peripheral joints, inflammatory or nocturnal pain in the axial skeleton; evidence of enthesitis (especially in the Achilles tendon or plantar fascia); current dactylitis (defined as swelling of the entire digit); or prior history of dactylitis diagnosed by a rheumatologist (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 5. If PsA is suspected, the dermatologist should refer the patient to a rheumatologist and provide a report including the PASI score, the percentage of affected BSA, and the current treatment regimen for psoriasis. This should be accompanied by a proposal for joint management of the patient's condition (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 6. When a patient diagnosed with PsA is referred by a rheumatologist for assessment, the dermatologist must investigate the current presence of psoriasis, paying particular attention to the sites typically associated with PsA (nails, intergluteal/perianal region, scalp, etc.). If active psoriasis is confirmed, the rheumatologist should be informed. The report should include the current PASI score and BSA (%) and a proposal for joint management of the patient's condition (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 7. Patients referred by a rheumatologist who do not have active psoriasis should be informed of the possibility that they will develop the skin disorder and the advisability of requesting a dermatology consultation if they should observe skin or nail lesions (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 83%). |

| 8. If a patient presents palmoplantar pustulosis and musculoskeletal pain, the dermatologist must investigate the skin lesions and refer the patient to the rheumatologist to complete the differential diagnosis with SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 92%). |

| 9. The treatment plan for the patient with PsA should be devised jointly by the rheumatologist and the dermatologist taking into account the skin lesions as well as the involvement of peripheral and axial joints and entheses (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 10. Patients with controlled psoriasis who do not require additional monitoring related to their treatment regimen should be assessed once a year (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 92%). |

| 11. Both specialists should be involved in assessing the effectiveness of treatment (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 92%). |

| 12. Any decision to modify or continue treatment should be agreed by both specialists 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 13. If the dermatologist confirms the presence of paradoxical psoriasis in a patient with PsA receiving biologic therapy, the patient should be prescribed the appropriate topical or systemic treatment depending on the severity or extension of the lesions. The rheumatologist should decide whether the biologic therapy should be continued, switched, or withdrawn depending on the severity of the cutaneous involvement and the response to the current treatment regimen (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

Abbreviations: BSA, Body Surface Area; GR, grade of recommendation, LE, level of evidence; PASI: Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PsA psoriatic arthritis; RA, rate of agreement.

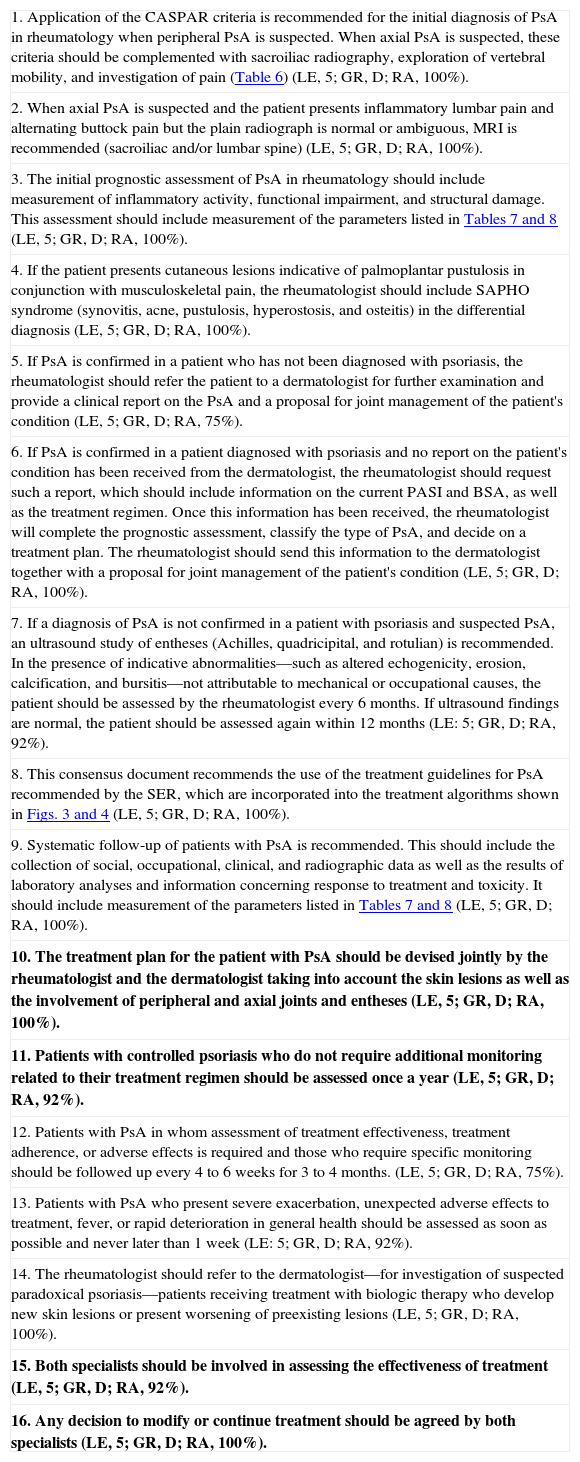

Recommendations for Rheumatologistsa

| 1. Application of the CASPAR criteria is recommended for the initial diagnosis of PsA in rheumatology when peripheral PsA is suspected. When axial PsA is suspected, these criteria should be complemented with sacroiliac radiography, exploration of vertebral mobility, and investigation of pain (Table 6) (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 2. When axial PsA is suspected and the patient presents inflammatory lumbar pain and alternating buttock pain but the plain radiograph is normal or ambiguous, MRI is recommended (sacroiliac and/or lumbar spine) (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 3. The initial prognostic assessment of PsA in rheumatology should include measurement of inflammatory activity, functional impairment, and structural damage. This assessment should include measurement of the parameters listed in Tables 7 and 8 (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 4. If the patient presents cutaneous lesions indicative of palmoplantar pustulosis in conjunction with musculoskeletal pain, the rheumatologist should include SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) in the differential diagnosis (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 5. If PsA is confirmed in a patient who has not been diagnosed with psoriasis, the rheumatologist should refer the patient to a dermatologist for further examination and provide a clinical report on the PsA and a proposal for joint management of the patient's condition (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 75%). |

| 6. If PsA is confirmed in a patient diagnosed with psoriasis and no report on the patient's condition has been received from the dermatologist, the rheumatologist should request such a report, which should include information on the current PASI and BSA, as well as the treatment regimen. Once this information has been received, the rheumatologist will complete the prognostic assessment, classify the type of PsA, and decide on a treatment plan. The rheumatologist should send this information to the dermatologist together with a proposal for joint management of the patient's condition (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 7. If a diagnosis of PsA is not confirmed in a patient with psoriasis and suspected PsA, an ultrasound study of entheses (Achilles, quadricipital, and rotulian) is recommended. In the presence of indicative abnormalities—such as altered echogenicity, erosion, calcification, and bursitis—not attributable to mechanical or occupational causes, the patient should be assessed by the rheumatologist every 6 months. If ultrasound findings are normal, the patient should be assessed again within 12 months (LE: 5; GR, D; RA, 92%). |

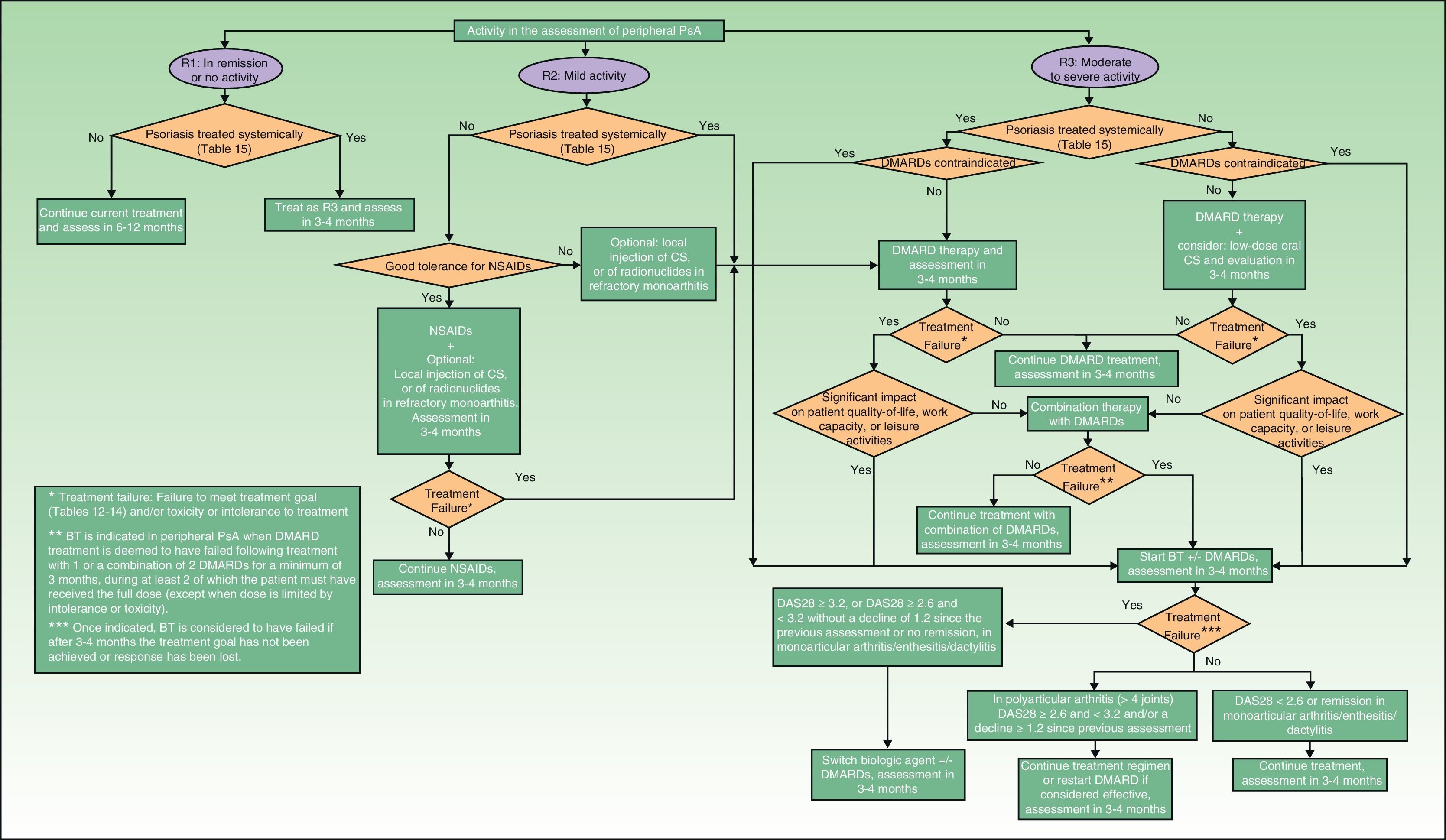

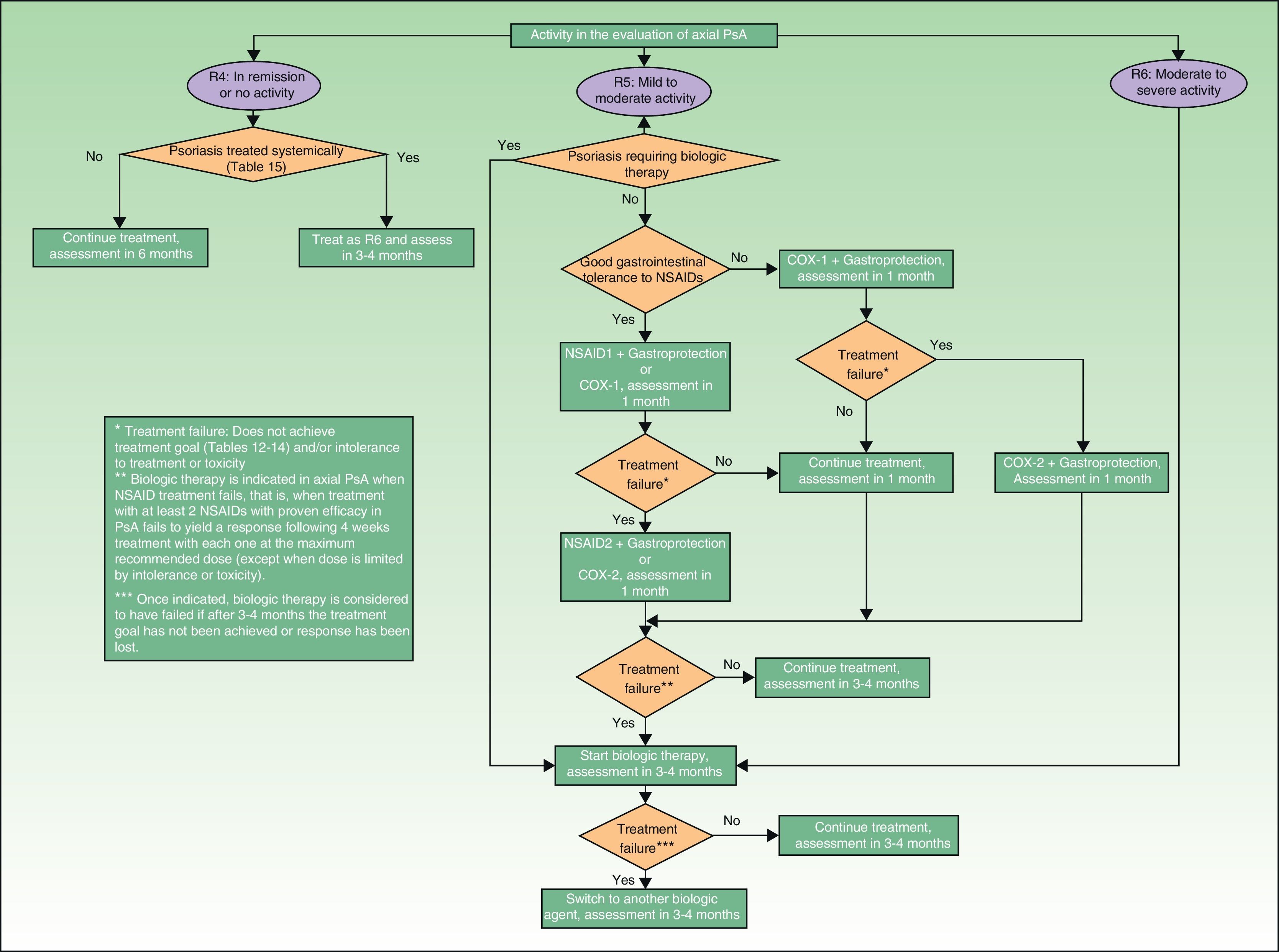

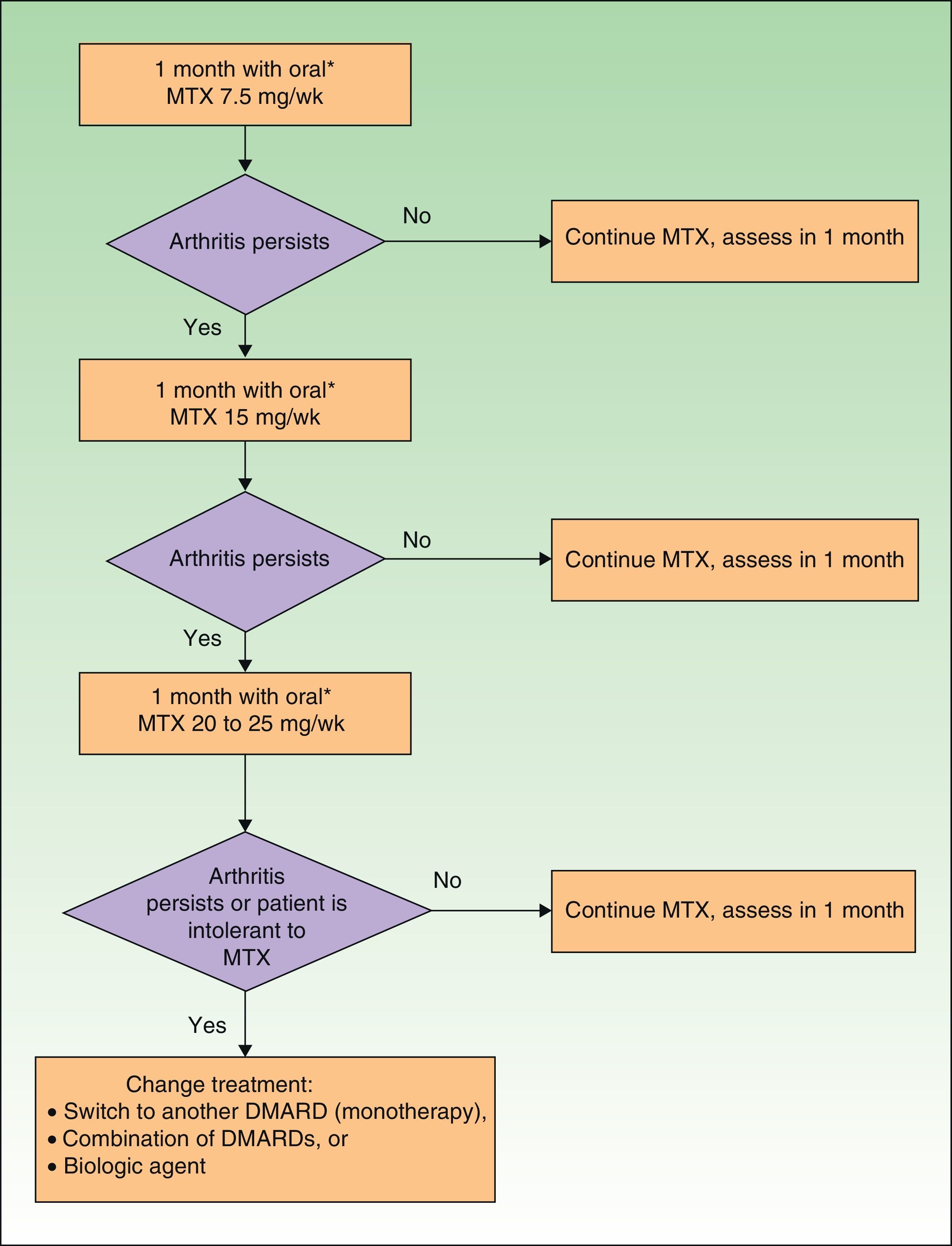

| 8. This consensus document recommends the use of the treatment guidelines for PsA recommended by the SER, which are incorporated into the treatment algorithms shown in Figs. 3 and 4 (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 9. Systematic follow-up of patients with PsA is recommended. This should include the collection of social, occupational, clinical, and radiographic data as well as the results of laboratory analyses and information concerning response to treatment and toxicity. It should include measurement of the parameters listed in Tables 7 and 8 (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 10. The treatment plan for the patient with PsA should be devised jointly by the rheumatologist and the dermatologist taking into account the skin lesions as well as the involvement of peripheral and axial joints and entheses (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 11. Patients with controlled psoriasis who do not require additional monitoring related to their treatment regimen should be assessed once a year (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 92%). |

| 12. Patients with PsA in whom assessment of treatment effectiveness, treatment adherence, or adverse effects is required and those who require specific monitoring should be followed up every 4 to 6 weeks for 3 to 4 months. (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 75%). |

| 13. Patients with PsA who present severe exacerbation, unexpected adverse effects to treatment, fever, or rapid deterioration in general health should be assessed as soon as possible and never later than 1 week (LE: 5; GR, D; RA, 92%). |

| 14. The rheumatologist should refer to the dermatologist—for investigation of suspected paradoxical psoriasis—patients receiving treatment with biologic therapy who develop new skin lesions or present worsening of preexisting lesions (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

| 15. Both specialists should be involved in assessing the effectiveness of treatment (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 92%). |

| 16. Any decision to modify or continue treatment should be agreed by both specialists (LE, 5; GR, D; RA, 100%). |

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; GR, grade of recommendation; LE, level of evidence; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SER, Sociedad Española de Reumatología; RA, rate of agreement.

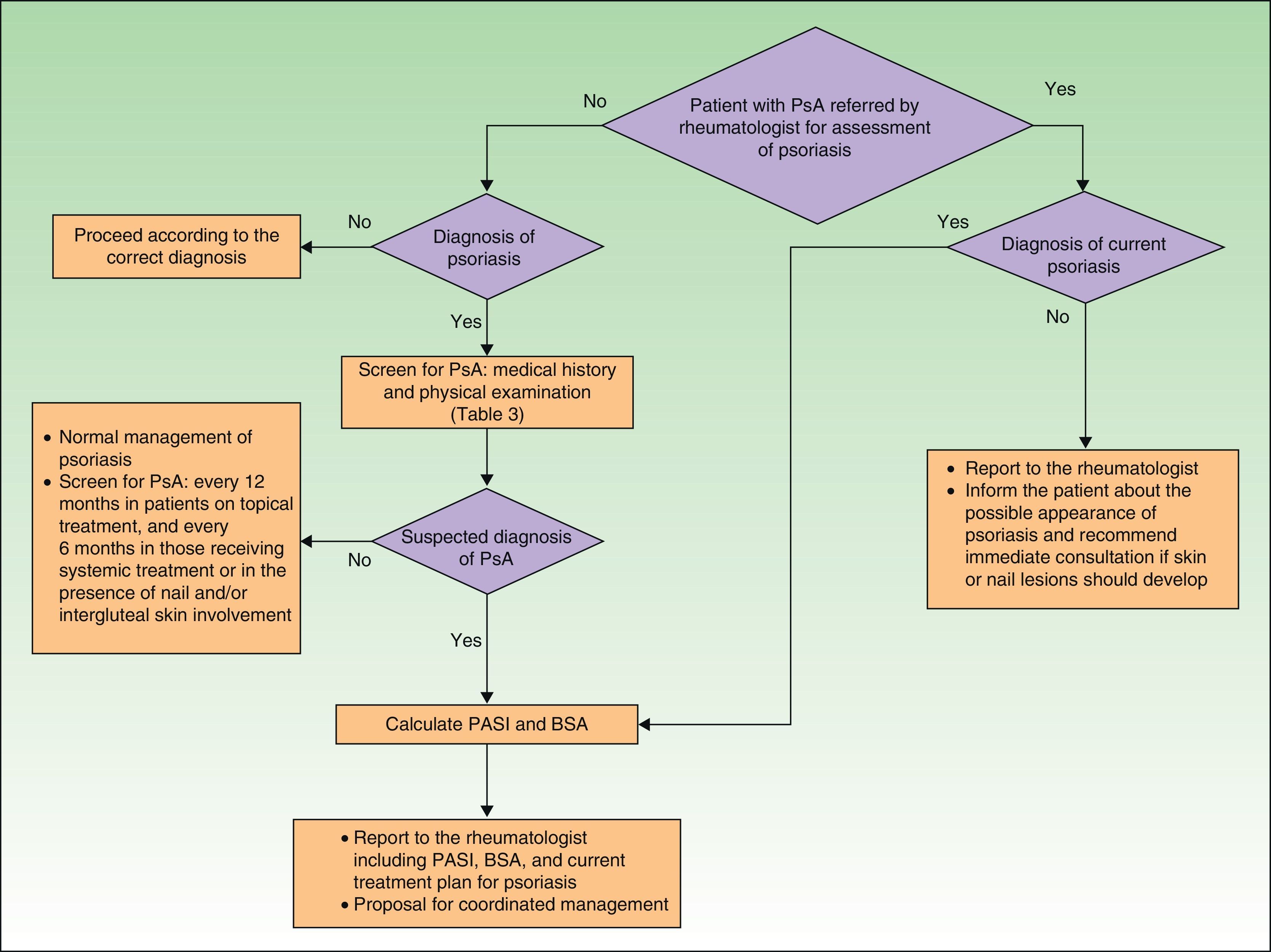

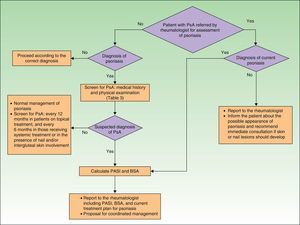

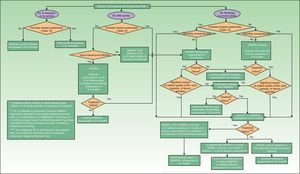

Fig. 1 is a detailed algorithm showing the procedure that should be used by dermatologists to screen for PsA.

In the clinical examination of a patient with psoriasis, the dermatologist should include screening for PsA at regular intervals. This is particularly important in patients with risk factors for PsA, such as onychopathy, obesity, extensive skin disease (>3areas affected by psoriasis), or involvement of sites such as the scalp and intergluteal cleft.

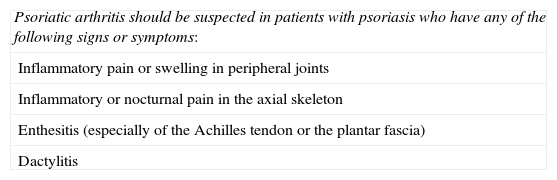

As mentioned in the publications of the AEDV Working Group on Comorbidity in Psoriasis,23,24 the CASPAR criteria are difficult to apply in clinical practice outside the rheumatology office because they require diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis and radiographic evidence of juxtaarticular new bone formation (excluding osteophyte formation). To address this problem, the working group proposed criteria for referral to a rheumatologist based on a simplified version of the CASPAR criteria (Table 3). These modified criteria are indicative of suspected PsA rather than a confirmed diagnosis.

Criteria for Suspected Diagnosis of Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA) (Based on a Simplified Version of the CASPAR Criteria).

| Psoriatic arthritis should be suspected in patients with psoriasis who have any of the following signs or symptoms: |

| Inflammatory pain or swelling in peripheral joints |

| Inflammatory or nocturnal pain in the axial skeleton |

| Enthesitis (especially of the Achilles tendon or the plantar fascia) |

| Dactylitis |

Source: Daudén et al.23

To apply this simplified adaptation of the CASPAR criteria, dermatologists must collect information on the presence or absence of the following signs and symptoms: inflammatory musculoskeletal pain (Table 4), current swelling of the peripheral joints (especially the knees, ankles, and the small joints of the hand), inflammatory or nocturnal pain in the axial skeleton (Table 5) or zones of tendon insertion, especially on the heels (Achilles tendon) and soles of the feet (plantar fascia).34 They must perform a visual inspection and exploration of suspect joints and entheses for redness, heat, limitation of mobility, swelling, and pain. The limbs should be examined to identify psoriatic onychopathy (nail dystrophy, onycholysis, pitting, or hyperkeratosis) or dactylitis (“sausage digits”, that is, swelling of an entire digit).23

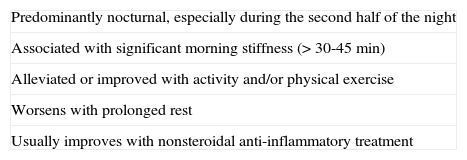

Characteristics of Inflammatory Pain in Peripheral Arthritis (Opinion of the Expert Panel).

| Predominantly nocturnal, especially during the second half of the night |

| Associated with significant morning stiffness (>30-45 min) |

| Alleviated or improved with activity and/or physical exercise |

| Worsens with prolonged rest |

| Usually improves with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory treatment |

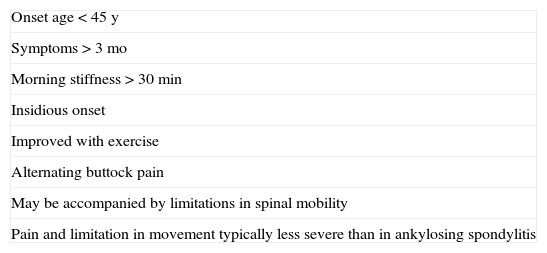

Characteristics of Axial Inflammatory Pain (Criteria of the GRAPPA Group).

| Onset age <45y |

| Symptoms >3 mo |

| Morning stiffness >30 min |

| Insidious onset |

| Improved with exercise |

| Alternating buttock pain |

| May be accompanied by limitations in spinal mobility |

| Pain and limitation in movement typically less severe than in ankylosing spondylitis |

Source: Ritchlin et al.27

When a patient diagnosed with PsA is referred to the dermatologist, the skin specialist will perform a thorough examination to look for psoriasis, paying particular attention to the sites most often associated with PsA (nails, scalp, intergluteal region, etc.). The dermatologist should then provide the rheumatologist with a report on the patient's psoriasis, including a proposal for coordinated management of the two conditions.

Certain skin lesions—especially palmoplantar pustulosis associated with musculoskeletal pain (mainly when this is located in the anterior thorax, but also when it affects the dorsal spine or unilateral sacroiliac joint, or takes the form of a monoarthritis affecting a large joint)—require a differential diagnosis with SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis). The dermatologist will study the skin lesions and refer the patient to a rheumatologist, who will study and classify the type of musculoskeletal disease.

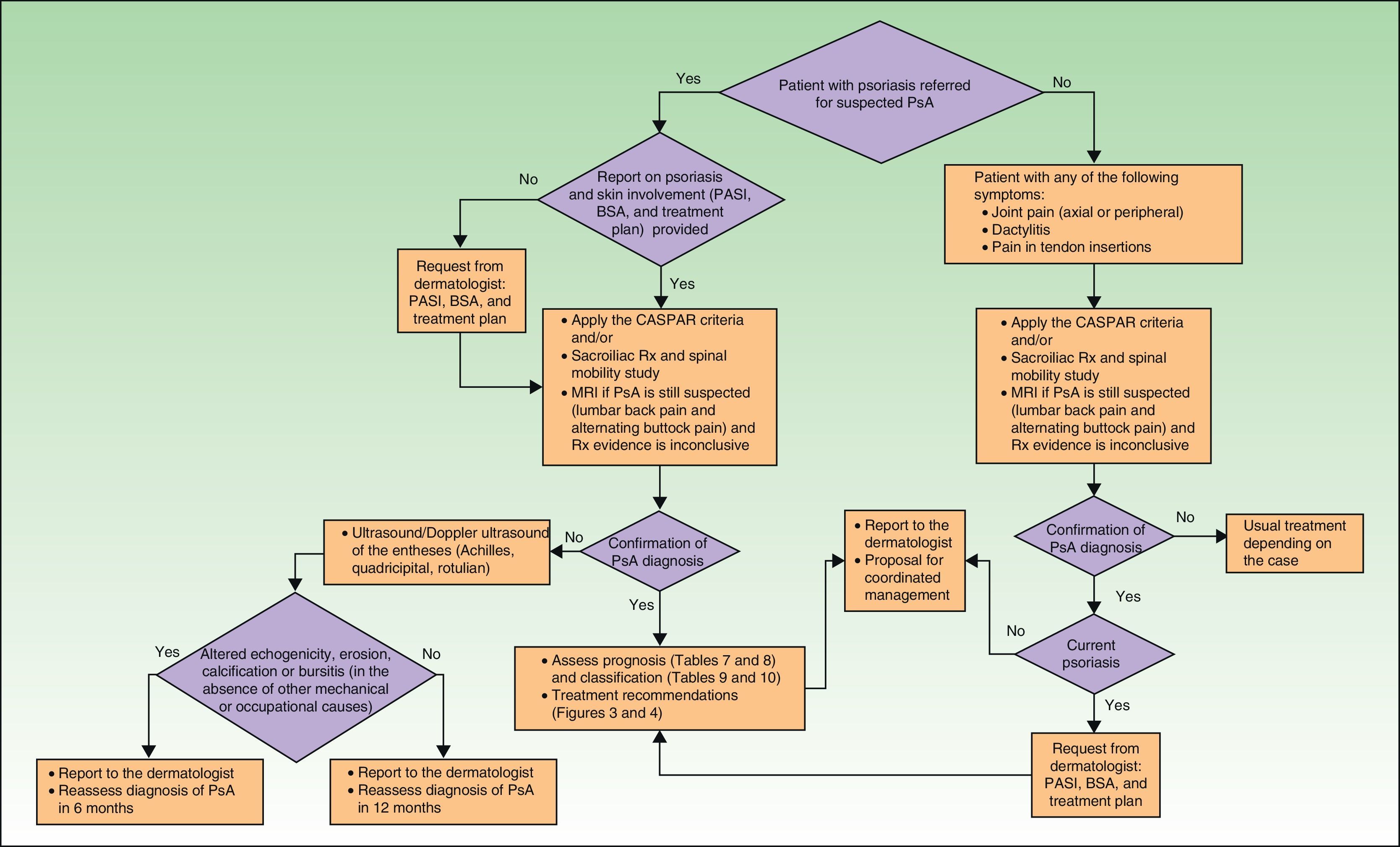

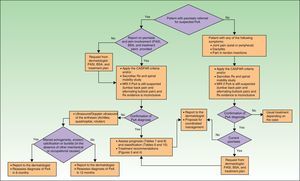

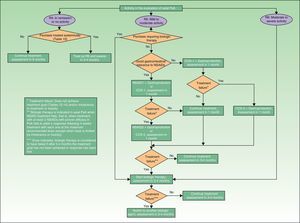

Screening for PsA and Assessment of Prognosis in the Rheumatology ClinicThe algorithm in Fig. 2 shows the procedure that should be used by rheumatologists to screen for PsA.

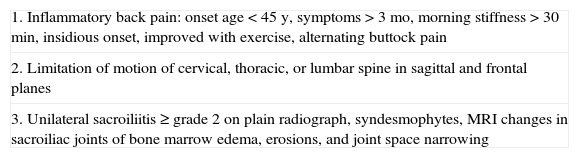

A suspected diagnosis of PsA may be established in the rheumatology consultation either in a patient with psoriasis referred by a dermatologist or in a patient (with or without psoriasis) who consults a rheumatologist for articular pain (joint or spine), dactylitis, and/or enthesitis. The CASPAR criteria (particularly when peripheral PsA is suspected),29 together with sacroiliac radiography and assessment of vertebral mobility (to detect axial PsA),27 can be useful in the initial diagnosis. Table 6 lists the GRAPPA criteria for the diagnosis of axial PsA.27 If enthesitis is suspected, Doppler ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging are useful to complement clinical examination of tendon, ligament, and capsular insertions for pain, inflammation, or tenderness on palpation or pressure.29 Dactylitis, a condition found in between 16% and 48% of patients with psoriatic joint disease, is an indicator of the severity of PsA.35 In some cases, isolated but recurrent episodes of dactylitis may be the only clinical manifestation of PsA.

Diagnostic Criteria for Axial Psoriatic Arthritisa

| 1. Inflammatory back pain: onset age <45y, symptoms >3 mo, morning stiffness >30 min, insidious onset, improved with exercise, alternating buttock pain |

| 2. Limitation of motion of cervical, thoracic, or lumbar spine in sagittal and frontal planes |

| 3. Unilateral sacroiliitis ≥ grade2 on plain radiograph, syndesmophytes, MRI changes in sacroiliac joints of bone marrow edema, erosions, and joint space narrowing |

Abbreviation: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Source: Ritchlin et al.27

SAPHO syndrome is one of the disorders the rheumatologist must include in the differential diagnosis. It is an uncommon seronegative rheumatic condition associated with palmoplantar skin lesions of the pustulosis type that predominantly affects the sternocostal and sternoclavicular joints of the anterior chest wall, but can also give rise to sacroiliitis, dorsal vertebral involvement, and synovitis of the large joints. The features that distinguish SAPHO syndrome from PsA include the presence of hyperostosis, predominantly thoracic involvement, unilateral sacroiliac involvement, and nonerosive peripheral oligoarthritis.

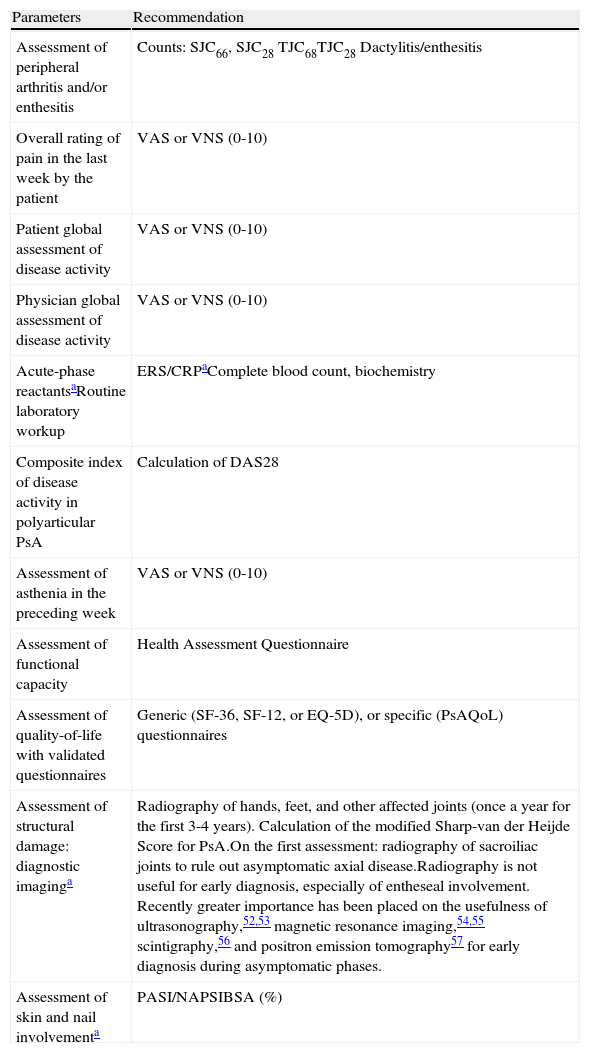

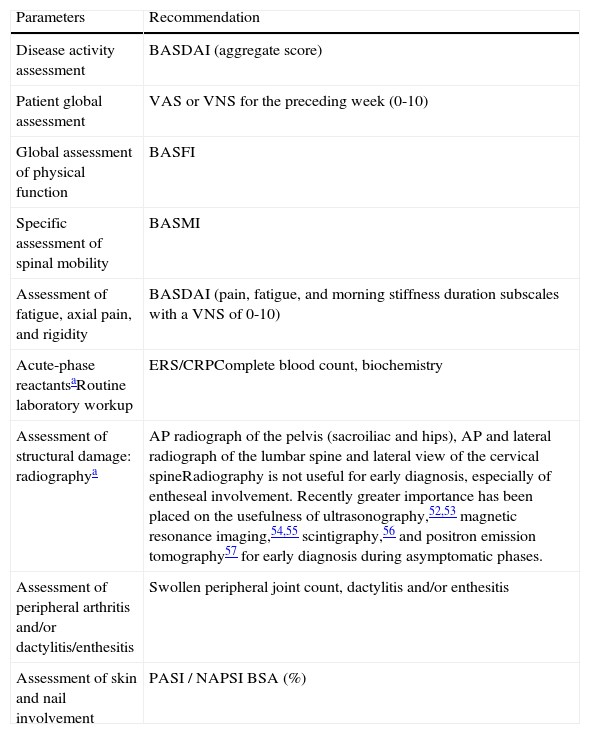

If the diagnosis of PsA is confirmed, the rheumatologist should carry out the initial assessment and identify the clinical form. This initial assessment should include a medical history, physical examination, laboratory tests, radiography. Standardized and validated evaluation tools should be used to classify the condition: the DAS28 (Disease Activity Score based on 28joint counts) to establish peripheral PsA involvement and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) in the case of axial disease. The tools used should allow the clinician to measure inflammatory activity, function, and structural damage, as well as the toxicity of treatment and response to therapy. Also of interest is the measurement of aspects—quality-of-life for instance—of vital interest to the patient. The results of this initial assessment will be used to establish criteria for remission and activity. Table 7 summarizes the parameters that should be taken into consideration in the assessment of peripheral PsA. It includes the parameters that should be assessed initially and those that should be taken into account when evaluating response to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID), DMARD, or biologic therapy. Table 8 lists the parameters that should be assessed in axial PsA. Both tables include assessment of skin and nail involvement, which, if not provided, should be requested from the dermatologist together with a treatment plan for the skin disease.

Assessment of Peripheral Psoriatic Arthritis: Parameters to be Monitored and Recommended Instruments.

| Parameters | Recommendation |

| Assessment of peripheral arthritis and/or enthesitis | Counts:SJC66, SJC28TJC68TJC28Dactylitis/enthesitis |

| Overall rating of pain in the last week by the patient | VAS or VNS (0-10) |

| Patient global assessment of disease activity | VAS or VNS (0-10) |

| Physician global assessment of disease activity | VAS or VNS (0-10) |

| Acute-phase reactantsaRoutine laboratory workup | ERS/CRPaComplete blood count, biochemistry |

| Composite index of disease activity in polyarticular PsA | Calculation of DAS28 |

| Assessment of asthenia in the preceding week | VAS or VNS (0-10) |

| Assessment of functional capacity | Health Assessment Questionnaire |

| Assessment of quality-of-life with validated questionnaires | Generic (SF-36, SF-12, or EQ-5D), or specific (PsAQoL) questionnaires |

| Assessment of structural damage: diagnostic imaginga | Radiography of hands, feet, and other affected joints (once a year for the first 3-4 years). Calculation of the modified Sharp-van der Heijde Score for PsA.On the first assessment: radiography of sacroiliac joints to rule out asymptomatic axial disease.Radiography is not useful for early diagnosis, especially of entheseal involvement. Recently greater importance has been placed on the usefulness of ultrasonography,52,53 magnetic resonance imaging,54,55 scintigraphy,56 and positron emission tomography57 for early diagnosis during asymptomatic phases. |

| Assessment of skin and nail involvementa | PASI/NAPSIBSA (%) |

Abbreviations: AP, anteroposterior; BSA, Body Surface Area; DAS28, Disease Activity Score; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions; ERS/CRP, erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PsAQoL, Psoriatic Arthritis Quality of Life Instrument; SF-36/12, Short Form-36/12 Health Survey; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; VAS, visual analog scale; VNS, visual numeric scale.

Source: Ritchlin et al.,27 Sociedad Española de Reumatología,28 and Fernández-Sueiro et al.29

Assessment of Axial Psoriatic Arthritis: Parameters to be Monitored and Recommended Instruments.

| Parameters | Recommendation |

| Disease activity assessment | BASDAI (aggregate score) |

| Patient global assessment | VAS or VNS for the preceding week (0-10) |

| Global assessment of physical function | BASFI |

| Specific assessment of spinal mobility | BASMI |

| Assessment of fatigue, axial pain, and rigidity | BASDAI (pain, fatigue, and morning stiffness duration subscales with a VNS of 0-10) |

| Acute-phase reactantsaRoutine laboratory workup | ERS/CRPComplete blood count, biochemistry |

| Assessment of structural damage: radiographya | AP radiograph of the pelvis (sacroiliac and hips), AP and lateral radiograph of the lumbar spine and lateral view of the cervical spineRadiography is not useful for early diagnosis, especially of entheseal involvement. Recently greater importance has been placed on the usefulness of ultrasonography,52,53 magnetic resonance imaging,54,55 scintigraphy,56 and positron emission tomography57 for early diagnosis during asymptomatic phases. |

| Assessment of peripheral arthritis and/or dactylitis/enthesitis | Swollen peripheral joint count, dactylitis and/or enthesitis |

| Assessment of skin and nail involvement | PASI / NAPSI BSA (%) |

Abbreviations: AP, anteroposterior; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; BSA, Body Surface Area; ERS/CRP, erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; VAS, visual analog scale; VNS, visual numeric scale.

Source: Ritchlin et al.,27 Sociedad Española de Reumatología,28 and Fernández-Sueiro et al.29

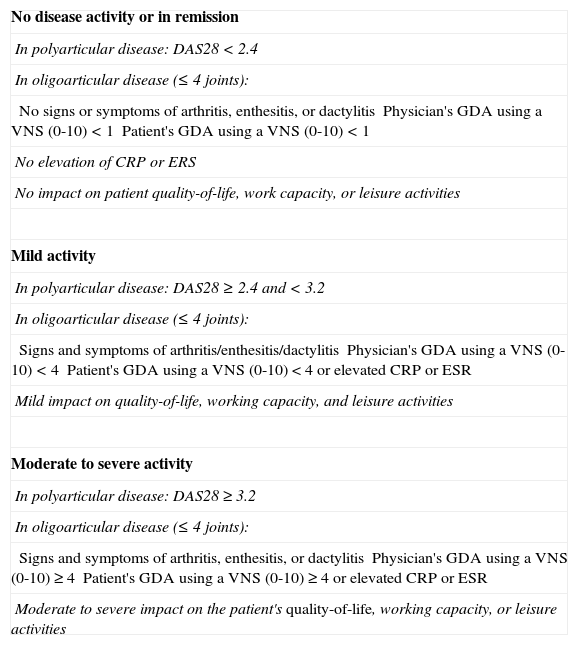

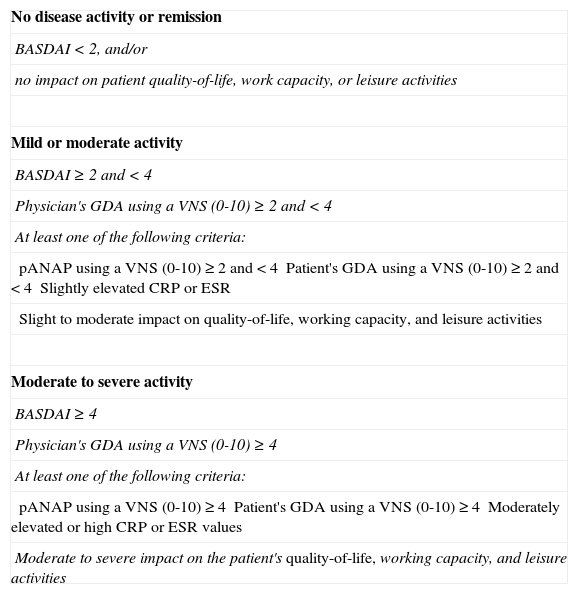

The clinical form of PsA is classified on the basis of the results of this initial evaluation. For practical purposes, PsA can be classified according to the predominant component of the joint disease as predominantly peripheral PsA (with or without an axial component) or predominantly axial (with or without a peripheral component). For the purposes of prognosis and treatment, both forms are also stratified according to the level of clinical activity (clinical signs and symptoms and acute-phase reactants), structural damage, functional impairment, and impact on quality-of-life. For the practical purposes outlined in this document, Tables 9 and 10 propose clinical classifications of peripheral and axial psoriatic arthritis based on the guidelines reviewed.27–29

Clinical Classification of Peripheral Psoriatic Arthritisa

| No disease activity or in remission |

| In polyarticular disease: DAS28<2.4 |

| In oligoarticular disease (≤4 joints): |

| No signs or symptoms of arthritis, enthesitis, or dactylitisPhysician's GDA using a VNS (0-10)<1Patient's GDA using a VNS (0-10)<1 |

| No elevation of CRP or ERS |

| No impact on patient quality-of-life, work capacity, or leisure activities |

| Mild activity |

| In polyarticular disease: DAS28≥2.4 and <3.2 |

| In oligoarticular disease (≤4 joints): |

| Signs and symptoms of arthritis/enthesitis/dactylitisPhysician's GDA using a VNS (0-10)<4Patient's GDA using a VNS (0-10)<4 or elevated CRP or ESR |

| Mild impact on quality-of-life, working capacity, and leisure activities |

| Moderate to severe activity |

| In polyarticular disease: DAS28≥3.2 |

| In oligoarticular disease (≤4 joints): |

| Signs and symptoms of arthritis, enthesitis, or dactylitisPhysician's GDA using a VNS (0-10)≥4Patient's GDA using a VNS (0-10)≥4 or elevated CRP or ESR |

| Moderate to severe impact on the patient's quality-of-life, working capacity, or leisure activities |

Abbreviations: BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; DAS28, Disease Activity Score; CRP, C-reactive protein; pANAP, patient assessment of nocturnal axial pain; GDA, global assessment of disease activity; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; VNS, visual numeric scale.

Clinical Classification of Axial Psoriatic Arthritisa

| No disease activity or remission |

| BASDAI<2, and/or |

| no impact on patient quality-of-life, work capacity, or leisure activities |

| Mild or moderate activity |

| BASDAI≥2 and <4 |

| Physician's GDA using a VNS (0-10)≥2 and <4 |

| At least one of the following criteria: |

| pANAP using a VNS (0-10)≥2 and <4Patient's GDA using a VNS (0-10)≥2 and <4Slightly elevated CRP or ESR |

| Slight to moderate impact on quality-of-life, working capacity, and leisure activities |

| Moderate to severe activity |

| BASDAI≥4 |

| Physician's GDA using a VNS (0-10)≥4 |

| At least one of the following criteria: |

| pANAP using a VNS (0-10)≥4Patient's GDA using a VNS (0-10)≥4Moderately elevated or high CRP or ESR values |

| Moderate to severe impact on the patient's quality-of-life, working capacity, and leisure activities |

Abbreviations: BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; GDA, global assessment of disease activity; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; pANAP, patient assessment of nocturnal axial pain; VNS, visual numeric scale.

Since the severity of PsA frequently does not correlate with that of psoriasis, the assessment must include a dermatology report, which should include information on the patient's Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score and the percentage of body surface area affected (% BSA), as well as the recommended treatment plan for the skin disease. The overall treatment plan should be developed jointly by the two specialists taking into account both joint and skin disease.

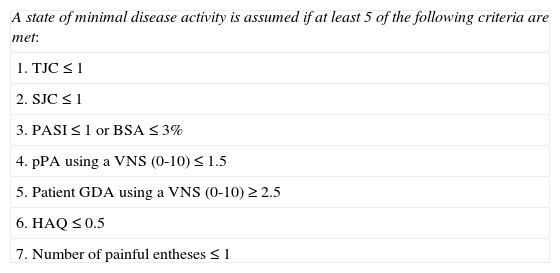

Coordinated Treatment Plan (Rheumatologist and Dermatologist) for Psoriatic ArthritisThe goal of treatment in PsA is to achieve remission of the disease or, at least, minimum disease activity (Table 11). This implies achieving significant improvement in signs and symptoms, preserving functional capacity, maintaining a good quality-of-life, and controlling structural damage.29,36Tables 12–14 list the objectives for each treatment in peripheral and axial PsA.29

Minimal Disease Activity: Criteria for Peripheral Psoriatic Arthritis.

| A state of minimal disease activity is assumed if at least 5 of the following criteria are met: |

| 1. TJC≤1 |

| 2. SJC≤1 |

| 3. PASI≤1 or BSA≤3% |

| 4. pPA using a VNS (0-10)≤1.5 |

| 5. Patient GDA using a VNS (0-10)≥2.5 |

| 6. HAQ≤0.5 |

| 7. Number of painful entheses≤1 |

Abbreviations: BSA Body Surface Area; GDA, global assessment of disease activity; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; PASI Psoriasis Area Severity Index; pPA, patient pain assessment; SJC swollen joint count; TJC: tender joint count; VNS, visual analog score.

Source: Coates et al.58

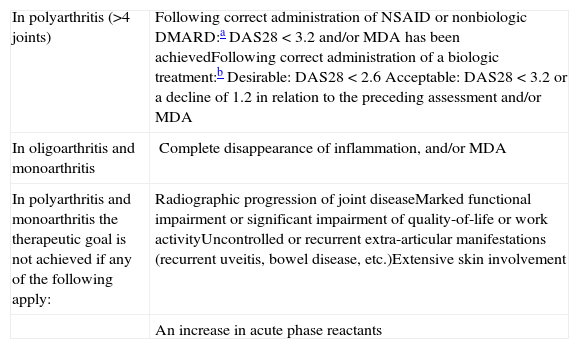

Treatment Goals in Predominantly Peripheral Psoriatic Arthritis.

| In polyarthritis (>4 joints) | Following correct administration of NSAID or nonbiologic DMARD:aDAS28<3.2 and/or MDA has been achievedFollowing correct administration of a biologic treatment:bDesirable: DAS28<2.6Acceptable: DAS28 <3.2 or a decline of 1.2 in relation to the preceding assessment and/or MDA |

| In oligoarthritis and monoarthritis | Complete disappearance of inflammation, and/or MDA |

| In polyarthritis and monoarthritis the therapeutic goal is not achieved if any of the following apply: | Radiographic progression of joint diseaseMarked functional impairment or significant impairment of quality-of-life or work activityUncontrolled or recurrent extra-articular manifestations (recurrent uveitis, bowel disease, etc.)Extensive skin involvement |

| An increase in acute phase reactants |

Abbreviations: DAS, Disease Activity Score; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; MDA, minimal disease activity; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

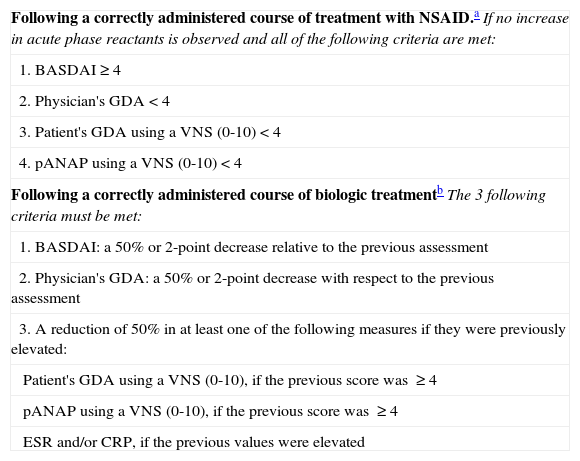

Treatment Goal in Predominantly Axial Psoriatic Arthritis.

| Following a correctly administered course of treatment with NSAID.aIf no increase in acute phase reactants is observed and all of the following criteria are met: |

| 1. BASDAI≥4 |

| 2. Physician's GDA<4 |

| 3. Patient's GDA using a VNS (0-10)<4 |

| 4. pANAP using a VNS (0-10)<4 |

| Following a correctly administered course of biologic treatmentbThe 3 following criteria must be met: |

| 1. BASDAI: a 50% or 2-point decrease relative to the previous assessment |

| 2. Physician's GDA: a 50% or 2-point decrease with respect to the previous assessment |

| 3. A reduction of 50% in at least one of the following measures if they were previously elevated: |

| Patient's GDA using a VNS (0-10), if the previous score was ≥4 |

| pANAP using a VNS (0-10), if the previous score was ≥4 |

| ESR and/or CRP, if the previous values were elevated |

Abbreviations: BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; ERS, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GDA, global assessment of disease activity; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; pANAP, patient assessment of nocturnal axial pain; VNS, visual numeric scale.

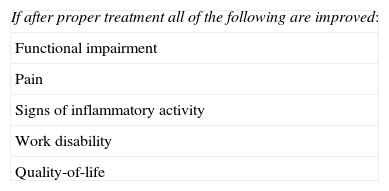

Treatment Objective After Correct Administrationa of Biologic Treatment in Dactylitis and/or Enthesitis.

| If after proper treatment all of the following are improved: |

| Functional impairment |

| Pain |

| Signs of inflammatory activity |

| Work disability |

| Quality-of-life |

NSAIDs, alone or in combination with local injections of corticosteroids, are useful in mild peripheral PsA with skin involvement that responds well to topical therapy (corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs) and UV-B or psoralen-UV-A phototherapy.

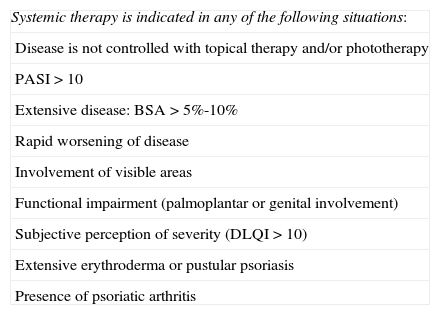

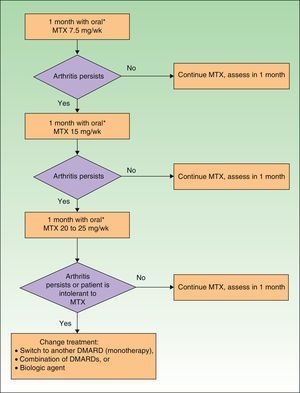

If the skin disease has not responded to earlier treatment or requires systemic therapy (Table 15), treatment with DMARDs (alone or in combinations) is recommended. In patients with moderate to severe peripheral PsA, DMARD treatment (monotherapy or in combinations) and even low dose corticosteroids are also recommended. If the patient also has skin disease, caution should be exercised with corticosteroid treatment, which may exacerbate psoriasis.27 In PsA, biologic therapy is indicated when treatment with DMARDs has failed or is contraindicated or the patient is intolerant to such treatment. Fig. 3 presents a treatment algorithm for peripheral PsA based on the SER consensus statement on the use of biologic agents in PsA.29 This algorithm includes criteria for treatment failure and recommendations for evaluating treatment.

Indications for Systemic Treatment in Psoriasis.

| Systemic therapy is indicated in any of the following situations: |

| Disease is not controlled with topical therapy and/or phototherapy |

| PASI>10 |

| Extensive disease: BSA>5%-10% |

| Rapid worsening of disease |

| Involvement of visible areas |

| Functional impairment (palmoplantar or genital involvement) |

| Subjective perception of severity (DLQI>10) |

| Extensive erythroderma or pustular psoriasis |

| Presence of psoriatic arthritis |

Abbreviations: BSA, Body Surface Area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index.

Source: Puig et al.37

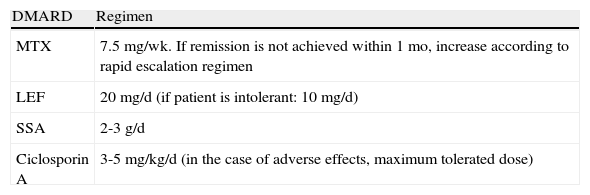

DMARDs with proven efficacy in peripheral PsA include sulfasalazine, methotrexate, leflunomide, and ciclosporinA, although the most highly recommended of these in PsA are methotrexate and leflunomide because of their risk-benefit profile.29 However, since methotrexate is the first-line choice among DMARDs in psoriasis, it is the recommended treatment in patients who have both psoriasis and PsA.37 The treatment regimens for DMARDs in PsA are summarized in Table 16.

Peripheral Psoriatic Arthritis: Initial Regimen (First 3 Months) for Each DMARD.

| DMARD | Regimen |

| MTX | 7.5mg/wk. If remission is not achieved within 1 mo, increase according to rapid escalation regimen |

| LEF | 20mg/d (if patient is intolerant: 10mg/d) |

| SSA | 2-3g/d |

| Ciclosporin A | 3-5mg/kg/d (in the case of adverse effects, maximum tolerated dose) |

Abbreviations: LEF, leflunomide, MTX, methotrexate, SSA, sulfasalazine.

Source: Fernández-Sueiro et al.29

In predominantly peripheral PsA, treatment with biologic therapy should be considered when an adequate response has not been obtained following treatment with DMARDs (monotherapy or a combination regimen) for at least 3months, during at least 2 of which the patient must receive the full dose (except when the dose is limited by intolerance or toxicity).29

Treatment with NSAIDs and physiotherapy are the first-line treatment in mild to moderate axial PsA when the skin disease does not require treatment with DMARDs or biologic therapy. However, since DMARDs have not been shown to be effective in axial PsA, biologic therapy is recommended when NSAID treatment fails to produce an adequate response or when the skin condition is refractory to topical therapy or requires systemic therapy. In predominantly axial PsA, biologic therapy is considered when treatment has failed with at least 2 NSAIDS having proven anti-inflammatory effect. In each case, the NSAID must have been administered for at least 4weeks at the maximum recommended or tolerated dose, except when there are contraindications to NSAIDs or evidence of toxicity.29 The treatment algorithm for axial PsA, also based on the SER consensus statement, is presented in Fig. 4.29

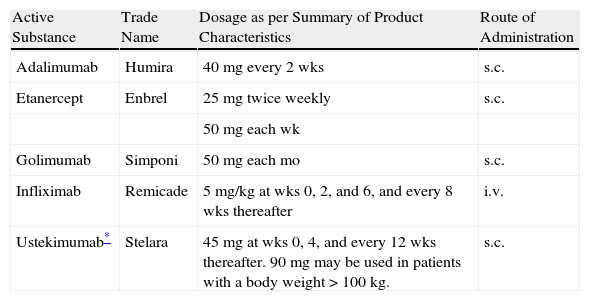

Four biologic agents are currently approved by the regulatory agencies for the treatment of the signs and symptoms of active PsA refractory to conventional therapies (Table 17): adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab (Fig. 5).

Dosage and Route of Administration of Biologic Therapies Approved for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis. First 52 Weeks of Treatment.

| Active Substance | Trade Name | Dosage as per Summary of Product Characteristics | Route of Administration |

| Adalimumab | Humira | 40mg every 2wks | s.c. |

| Etanercept | Enbrel | 25mg twiceweekly | s.c. |

| 50mg each wk | |||

| Golimumab | Simponi | 50mg each mo | s.c. |

| Infliximab | Remicade | 5mg/kg at wks 0, 2, and 6, and every 8 wks thereafter | i.v. |

| Ustekimumab* | Stelara | 45mg at wks 0, 4, and every 12 wks thereafter. 90mg may be used in patients with a body weight > 100 kg. | s.c. |

Abbreviations: i.v., intravenous; s.c. subcutaneous.

There is currently insufficient evidence from direct comparisons to support the use of one biologic agent rather than another in the treatment of PsA.38 Consequently the choice of treatment depends on the physician's criteria, the particular circumstances of each patient, and the structure, antigenicity, and mechanisms of action of the different biologic therapies.39 In the databases of international registers and in observational studies, it appears that etanercept may be associated with longer drug survival than other anti-TNF agents in patients with PsA.40–42

If within 3 to 4 months of starting biological therapy no response has been obtained (in polyarticular PsA, a DAS28 higher than 3.2 or between 2.6 and 3.2 without a decline of 1.2points over the previous assessment) or if the initial response has been lost, there is no evidence to support a change in the dose of the current biologic agent. Thus, an alternative treatment strategy should be considered, that is, a switch to another biologic agent. If the response is acceptable (in polyarticular PsA, DAS28 between 2.6 and 3.2 and/or a decrease of 1.2points compared to the previous value), treatment should be continued with the possible addition of a DMARD. If the treatment goal has been achieved, treatment should be continued and response assessed in 3 to 4months.29

There is currently insufficient evidence in patients with PsA receiving biologic therapy whose condition is in remission to support a recommendation for reducing the dose or prolonging the interval between doses, although a reduction in treatment intensity can be considered on a case-by-case basis.29 Some authors have published their experience with dose reduction in this setting.43 This topic is currently considered to be a priority research target.36

Coordinated Management (Rheumatologist and Dermatologist) of Psoriatic ArthritisAs there is very little information in the literature concerning the monitoring and follow-up of patients with PsA,44–46 recommendations are based on expert opinion.

As a general rule, the rheumatologist is in charge of the management of PsA, but the dermatologist who detects signs or symptoms indicative of a worsening of PsA should refer the patient to the rheumatologist. The dermatologist will also agree with the rheumatologist any change in the patient's treatment that might directly affect the course of PsA (in particular changes in DMARD or biologic therapy). Likewise, the rheumatologist will agree with the dermatologist on any change in therapy that might directly affect the course of psoriasis (in particular changes in DMARD or biologic therapy).

The assessment undertaken by the rheumatologist on follow-up of patients with PsA will be shorter and more specific than the initial evaluation; the findings of the physical examination, complete blood count, routine biochemistry, CRP, and ESR together with an assessment of prognosis should all be recorded in the patient's clinical records. The follow-up visit provides an opportunity to assess the activity of PsA and to evaluate adherence and response to treatment and identify any adverse effects.

Tables 7 and 8 list the parameters that should be assessed and the recommended instruments for use in the follow-up of PsA. In order to assess disease activity, objective data will be collected and recorded, including tender and swollen joint counts, the presence of dactylitis or enthesitis, and the physician's global disease assessment. At the same time subjective data will be collected, including the patient's assessment of disease activity and pain during the preceding week using a visual numeric scale (VNS). The results of laboratory tests indicative of inflammation, such as CRP and ESR, will also be recorded together with an assessment of the impact of the disease on the patient's social and working life (asthenia, functional capacity, quality-of-life). It may also be useful to record information on the use of symptomatic treatments. Use of the DAS28 to assess treatment response is recommended in polyarticular forms in spite the limitations of the instrument. Although the DAS28 was developed specifically to assess rheumatoid arthritis, the rheumatologist's familiarity with its use and the fact that the calculator can measure response to treatment make it an attractive tool for monitoring polyarticular forms of PsA in routine practice. The BASDAI is the recommended method for assessing treatment response in axial PsA. Monitoring aimed at identifying adverse effects to therapy should include complete blood count and routine biochemistry in addition to the specific tests required for each drug.

The results of skin and nail assessment should also be recorded, especially in moderate to severe psoriasis. The patient should be referred to a dermatologist for a report on PASI and BSA scores and to obtain a proposed treatment plan if this is considered clinically necessary.

Radiographs of symptomatic joints must be obtained during patient follow-up. Anteroposterior radiographs of the hands and feet should be obtained if the PsA is polyarticular. These should be obtained annually for the first 3 to 4years after onset, after which the frequency will depend on disease activity.

If the disease is well controlled and not acute and the patient does not require special monitoring related to the drug regimen or other circumstances, follow-up visits should be scheduled every 6 to 12months. When it is necessary to establish the effectiveness of a therapeutic intervention or monitor compliance, or when the clinical situation demands more frequent consultations, follow up visits should be scheduled every 4 to 6weeks for up to 4months after start of treatment or stabilization of symptoms.

Biologic therapy occasionally triggers a paradoxical reaction that can provoke an exacerbation of existing lesions or de novo psoriasis in patients with no prior skin involvement. These flares of psoriasis associated with biologic therapy can appear within days of the start of anti-TNF therapy or after years of treatment. The most common presentation is palmoplantar psoriasis, either pustular or hyperkeratotic. The choice of treatment in such cases will depend on the extent of the lesions and their response to topical treatment. Tolerable lesions with a BSA of less than 5% to 10% should be treated topically with corticosteroids, keratolytic agents, or vitamin D analogs. If the condition does not improve, switching to another biologic agent or discontinuation of biologic therapy should be considered. If the lesions are tolerable but the BSA is greater than 5% to 10% or the patient has palmoplantar involvement, a switch to another biologic agent and the addition of topical therapy with occlusive corticosteroids in combination with phototherapy, acitretin, and/or a DMARD (MTX or ciclosporin A) may be considered; if the problem does not improve, a switch to another biologic agent or discontinuation of biologic therapy should be considered. When the lesions are more severe or the patient finds them intolerable or wishes to discontinue the treatment regimen, biologic therapy should be discontinued and topical treatment initiated. The rheumatologist should refer to the dermatologist any patients receiving treatment with biologic therapy who develop skin disease or experience worsening of existing lesions.47,48 If de novo psoriasis develops or existing psoriasis is exacerbated, the dermatologist will propose an appropriate treatment plan to the rheumatologist, taking into account the severity and extent of the skin involvement.

Communication between the primary care physician, dermatology and rheumatology should be prompt and efficient.

DiscussionIn recent years, there has been a growing interest in the study of PsA and its consideration as a separate clinical entity from other forms of spondyloarthritis. Its association with psoriasis, the involvement of peripheral joints, the presence of dactylitis, and the peculiarities of its axial involvement compared to ankylosing spondylitis make it advisable to consider PsA as a separate and distinct disease requiring specific assessment and management.

Recent publications include 2 review articles on PsA written for dermatologists49,50 and numerous guidelines and recommendations for its management, some addressed mainly to rheumatologists27–31 and others to dermatologists.23–26 Recent publications of the Working Group on Comorbidity in Psoriasis23,24 address the role of the dermatologist and deal with the diagnosis of PsA and the referral of these patients to a rheumatologist. They do not, however, discuss in depth the role of the dermatologist in the management of PsA or how rheumatologists and dermatologists should work together to decide on the most appropriate treatment regimen in each case and evaluate treatment response taking into account the clinical features of both psoriasis and PsA.

The authors of the multicenter CALIPSO study undertaken a few years ago in Spain observed substantial differences in the clinical management and follow-up of patients with PsA depending on whether they were treated in rheumatology or dermatology clinics.51 Those authors considered that these differences were indicative of a lack of consensus on the correct approach in PsA and recommended the development of standardized practice guidelines covering the diagnostic protocols, classification, management of symptoms and treatment, and criteria for referral between the two specialties. The present document was drawn up to address this problem and to complement existing guidelines and consensus statements by providing specific recommendations aimed at unifying the criteria and improving the coordinated management of PsA by dermatologists and rheumatologists.

The fact that the present document is not based on a systematic review of the literature does not constitute a limitation. The review was performed to identify the customary and accepted tools for the diagnosis, assessment, and therapeutic management of PsA, which were then used as a framework to support the project. They provided the structure for the recommendations made by the panelists for coordinated management of PsA.

The recommendations are based solely on expert opinion. To make them more robust we used a strict criterion based on clear consensus among the panelists (at least 70% endorsement with the 3highest categories). Moreover, the panel was made up of both rheumatologists and dermatologists and the recommendations were endorsed by both groups. Thus, it is hoped that these recommendations will prove useful in the coordinated management of PsA.

In conclusion, this document contains recommendations and guidelines for improving the coordinated management of PsA between dermatologists and rheumatologists. It will be of particular interest and benefit to dermatologists because of the key role they play in the early diagnosis and referral of patients with PsA and in assessing any skin involvement to provide the information needed to establish a prognosis and devise a treatment plan for these patients.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of Human and Animal SubjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of DataThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Right to Privacy and Informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

FundingThis work was carried out with independent financing from Pfizer S.L.U.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors whose names are indicated in parentheses have received remuneration for expert consulting, participation in clinical trials, or conferences from the companies listed below: Abbvie (Juan de Dios Cañete, Esteban Daudén, Gregorio Carretero, Lluís Puig, José Luis Sánchez-Carazo, and José Luis López-Estebaranz); Celgene (Juan de Dios Cañete, Esteban Daudén, and Lluís Puig); Janssen-Cilag (Juan de Dios Cañete, Esteban Daudén, Gregorio Carretero, Lluís Puig, and José Luis López-Estebaranz); MSD and/or MSD-Schering-Plough, and/or Merck Serono (Juan de Dios Cañete, Esteban Daudén, Gregorio Carretero, Lluís Puig, José Luis Sánchez-Carazo, and José Luis López-Estebaranz); Pfizer and/or Wyeth and/or Pfizer-Wyeth (Juan de Dios Cañete, Esteban Daudén, Gregorio Carretero, Lluís Puig, José Luis Sánchez-Carazo, and José Luis López-Estebaranz); Amgen (Esteban Daudén and Lluís Puig); Astellas (Esteban Daudén); Boehringer (Lluís Puig); Centocor Ortho Biotech Inc (Esteban Daudén and Lluís Puig); Galderma (Esteban Daudén); Glaxo and/or GSK (Esteban Daudén); Leo Pharma (Esteban Daudén, Gregorio Carretero, and Lluís Puig); Novartis (Esteban Daudén, Gregorio Carretero, and Lluís Puig), and VBL (Lluís Puig).

The other authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest in relation to the content of the present article. All of the authors consider that they have acted with total independence with respect to the drafting of this article.

In memory of Dr. José Luis Fernández Sueiro, the rheumatologist who pioneered collaboration between dermatologists and rheumatologists in the study and management of psoriatic arthritis.

Please cite this article as: Cañete JD, Daudén E, Queiro R, Aguilar MD, Sánchez-Carazo JL, Carrascosa JM, et al. Elaboración mediante el método Delphi de recomendaciones para el manejo coordinado (reumatólogo/dermatólogo) de la artritis psoriásica. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:216–232.