In the routine clinical practice in dermatology, there is a high burden of psychiatric morbidity due to primary psychiatric disorders that secondarily affect the skin or dermatological disorders that secondarily can have a profound psychosocial and mental health impact. We present a narrative review on the use of psychotropic drugs, with the aim of addressing the intersection between mental health and dermatology. The article aims to be a practical guide, providing clear and concise recommendations on the indications, dosing, adverse effects, special considerations, or contraindications of the most widely used drugs today, with the goal of providing dermatologists with the basic tools for the appropriate global therapeutic management of these patients.

In routine dermatologic practice, there is a high burden of psychiatric morbidity, with an estimated incidence of 30–60%.1,2 The skin and the nervous system share a common embryologic origin in the ectoderm and are regulated by multiple shared neuroendocrine pathways, resulting in an intimate and complex connection.3 Psychodermatology is the field dedicated to the study and management of cutaneous and psychiatric conditions arising from the interaction between the skin and the psyche.3

Patients may present to dermatology either with primary psychiatric disorders that secondarily affect the skin or one's perception of self, or with primary dermatologic diseases that secondarily cause significant psychosocial and mental health impact. It is common for patients to refuse referral to psychiatry due to stigma or lack of acceptance of the psychological component of their disease.4 Dermatologists should support these patients in a nonjudgmental manner, possess the basic knowledge required to manage the indicated psychotropic drugs, and encourage psychiatric evaluation as a complementary approach rather than a substitute for the therapeutic relationship.

Management of psychodermatologic disorders requires psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions, as well as the use of psychotropic drugs. Exploration of psychosocial stressors, effective communication, and the development of a strong therapeutic alliance can be critical for treatment adherence and success.5 This narrative review focuses on the role of psychotropic drugs, aiming to provide dermatologists with essential tools for the appropriate management of these patients.

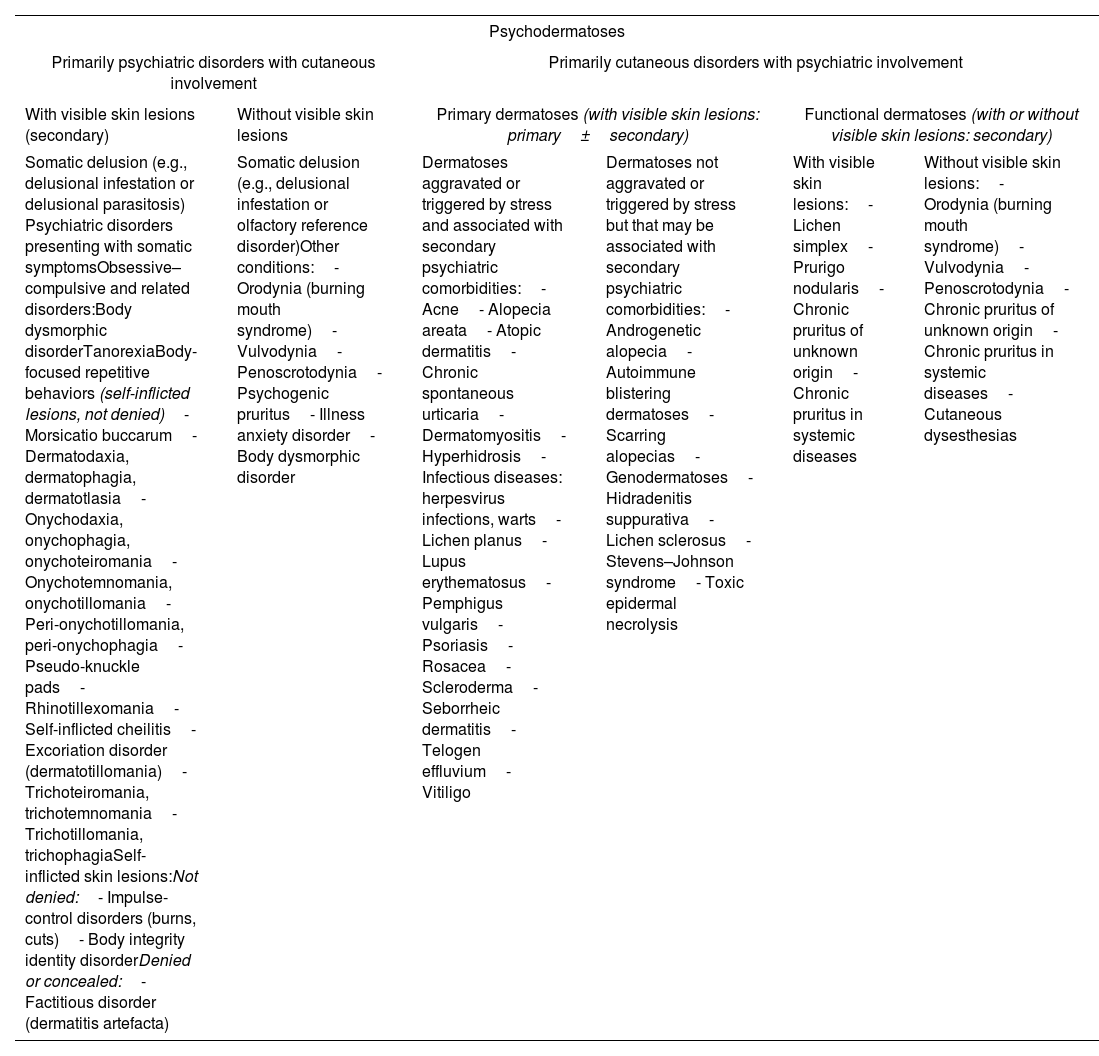

Classification of psychodermatosesSeveral classifications of psychodermatoses have been proposed. Most distinguish four major categories: psychophysiological skin disorders (primary dermatoses aggravated or triggered by stress), primary psychiatric disorders (with secondary cutaneous signs), secondary psychiatric disorders (arising from the psychosocial impact of primary dermatoses), and cutaneous sensory disorders (cutaneous symptoms occurring without clear primary skin disease). However, until recently, there was no expert consensus-based classification specific to psychodermatology. The DSM-5-TR (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, Text Revision) and ICD-11 (International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision) also do not provide a systematic framework for psychodermatologic disorders.

Recently, an international expert consensus proposed a new practical classification based on two major categories (Table 1), with the goal of improving recognition of psychodermatologic disorders and optimizing patient management.6

Classification of psychodermatoses.

| Psychodermatoses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primarily psychiatric disorders with cutaneous involvement | Primarily cutaneous disorders with psychiatric involvement | ||||

| With visible skin lesions (secondary) | Without visible skin lesions | Primary dermatoses (with visible skin lesions: primary±secondary) | Functional dermatoses (with or without visible skin lesions: secondary) | ||

| Somatic delusion (e.g., delusional infestation or delusional parasitosis) Psychiatric disorders presenting with somatic symptomsObsessive–compulsive and related disorders:Body dysmorphic disorderTanorexiaBody-focused repetitive behaviors (self-inflicted lesions, not denied)- Morsicatio buccarum- Dermatodaxia, dermatophagia, dermatotlasia- Onychodaxia, onychophagia, onychoteiromania- Onychotemnomania, onychotillomania- Peri-onychotillomania, peri-onychophagia- Pseudo-knuckle pads- Rhinotillexomania- Self-inflicted cheilitis- Excoriation disorder (dermatotillomania)- Trichoteiromania, trichotemnomania- Trichotillomania, trichophagiaSelf-inflicted skin lesions:Not denied:- Impulse-control disorders (burns, cuts)- Body integrity identity disorderDenied or concealed:- Factitious disorder (dermatitis artefacta) | Somatic delusion (e.g., delusional infestation or olfactory reference disorder)Other conditions:- Orodynia (burning mouth syndrome)- Vulvodynia- Penoscrotodynia- Psychogenic pruritus- Illness anxiety disorder- Body dysmorphic disorder | Dermatoses aggravated or triggered by stress and associated with secondary psychiatric comorbidities:- Acne- Alopecia areata- Atopic dermatitis- Chronic spontaneous urticaria- Dermatomyositis- Hyperhidrosis- Infectious diseases: herpesvirus infections, warts- Lichen planus- Lupus erythematosus- Pemphigus vulgaris- Psoriasis- Rosacea- Scleroderma- Seborrheic dermatitis- Telogen effluvium- Vitiligo | Dermatoses not aggravated or triggered by stress but that may be associated with secondary psychiatric comorbidities:- Androgenetic alopecia- Autoimmune blistering dermatoses- Scarring alopecias- Genodermatoses- Hidradenitis suppurativa- Lichen sclerosus- Stevens–Johnson syndrome- Toxic epidermal necrolysis | With visible skin lesions:- Lichen simplex- Prurigo nodularis- Chronic pruritus of unknown origin- Chronic pruritus in systemic diseases | Without visible skin lesions:- Orodynia (burning mouth syndrome)- Vulvodynia- Penoscrotodynia- Chronic pruritus of unknown origin- Chronic pruritus in systemic diseases- Cutaneous dysesthesias |

e.g., for example.

Morsicatio buccarum: compulsion to bite one's own oral mucosa, even tearing pieces of the mucosa. Dermatodaxia: compulsion to bite one's own skin without ingesting it. Dermatophagia: compulsion to bite and ingest one's own skin. Dermatotlasia: compulsion to rub or pinch one's own skin until bruising occurs. Onychodaxia: compulsion to bite a single nail to produce pleasurable pain. Onychophagia: compulsion to bite one's fingernails. Onychoteiromania: compulsion to rub or scratch the nails. Onychotemnomania: compulsion to cut the nails excessively short, causing trauma to the hyponychium or nail fold. Onychotillomania: compulsion to manipulate, pinch, or remove the cuticle, traumatizing the paronychium. Peri-onychotillomania: compulsion to pinch and tear the periungual skin. Peri-onychophagia: compulsion to bite and ingest the periungual skin. Pseudo–knuckle pads: compulsion to rub, chew, or suck the finger joints. Rhinotillexomania: compulsion to pick one's nose. Self-inflicted cheilitis: compulsion to lick one's lips. Excoriation disorder (dermatotillomania): compulsion to scratch or pick at the skin. Trichoteiromania: compulsion to rub or scratch the scalp. Trichotemnomania: compulsion to cut one's hair. Trichotillomania: compulsion to pull out one's hair. Trichophagia: compulsion to ingest the pulled hair, with risk of trichobezoars.

The psychotropic agents most widely used in routine dermatologic practice include antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and anxiolytics, among others.

AntidepressantsAntidepressants (Table 2) are the most frequently used psychotropic drugs in dermatology, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, and atypical antidepressants.7 Less commonly, other antidepressant classes are used, such as selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).7

Main antidepressants in dermatology.

| Drug | Dose | AEs | Other notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) | |||

| Citalopram (Calton®, Citalvir®, Prisdal®, Relapaz®, Seregra®, Seropram®) | 20–40mg/day (night)– Initial dose: 20mg/day– Increase by 20mg/day every 2–4 weeks if partial response– In particular cases (e.g., obsessive symptoms) doses may be increased up to 60mg/day | – GI discomfort (usually mild and transient at treatment onset)– Headache– Insomnia– Emotional changes (“blunting”, apathy)– Hyperhidrosis– Sexual dysfunction– Weight gain | Possible QTc prolongation |

| Escitalopram (Esertia®, Cipralex®, Heipram®) | 10–20mg/day (morning or night)– Initial dose: 5mg/day for first week, then 10mg/day– Increase by 5mg/day every 2–4 weeks if partial response– Up to 40mg/day in particular cases (e.g., obsessive symptoms) | Very low interaction profile Contraindicated in long-QT patients (though effects are possibly smaller than with citalopram) | |

| Sertraline (Altisben®, Aremis®, Aserin®, Besitran®, Semonic®) | 50–200mg/day (morning or night)– Initial dose: 25mg/day first week, then 50mg/day– Increase by 50mg/day every 2 weeks if partial response | Particularly safe in pregnancy and breastfeeding Safe in liver disease First choice in older adults | |

| Paroxetine (Arapaxel®, Casbol®, Daparox®, Frosinor®, Motivan®, Seroxat®, Xetin®) | 20–60mg/day (morning or night)– Initial dose: 20mg/day– Increase by 10mg/day every 2 weeks if partial response | More anticholinergic effects Higher rates of sexual dysfunction and increased appetite | |

| Fluoxetine (Adofen®, Prozac®, Luramon®, Reneuron®) | 20–60mg/day (morning)– Initial dose: 20mg/day– Increase by 20mg/day every 2–4 weeks if partial response | More interactions in polytherapy May reduce appetite initially | |

| Fluvoxamine (Dumirox®) | 100–300mg/day (night or divided doses)– Initial dose: 50mg/day– Increase by 50–100mg/day every 2–4 weeks if partial response | Divide doses when ≥150mg/day | |

| Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) | |||

| Venlafaxine (Arafaxina®, Conervin®, Dislaven®, Dobupal®, Flaxen®, Levest®, Vandral®, Venlabrain®, Venlamylan®, Venlapine®, Zarelis®) | 150–375mg/day (split in 2–3 doses)– Initial dose: 75mg/day– Increase by 75mg/day every 2–4 weeks– Dual action appears at >150mg/day | – Headache– Nausea, dizziness– Asthenia– Anxiety– Hyperhidrosis– Xerostomia– Constipation– Somnolence or insomnia– Hypertension (venlafaxine) | At high doses, monitor BP (First choice if prominent fatigue or pain) |

| Duloxetine (Cymbalta®, Xeristar®) | 60–120mg/day– Initial dose: 30mg/day first week, then 60mg/day | Favorable results even in fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue (First choice if prominent fatigue or pain) | |

| Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq®) | 50–200mg/day– Initial dose: 50mg/day– Increase by 50mg every 4 weeks if partial response | No hepatic metabolism effects Ideal in polytherapy (First choice if prominent fatigue or pain) | |

| Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) | |||

| Doxepin (Sinequan®, Silenor®) | 75–300mg/day (night)– Initial dose: 25mg/day– Increase by 10–25mg/day every 2 weeks if partial response | – Anticholinergic: xerostomia, blurry vision, constipation, urinary retention, glaucoma– Antiadrenergic: dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia– Antihistaminergic: sedation, weight gain– Others: decreased seizure threshold, hyperhidrosis, sexual dysfunction, confusion/memory issues, ECG changes (PR, QT, QRS prolongation) | Monitoring: baseline and periodic ECG in women>40 y and men>30 yAvoid alcohol contraindications:– Absolute: recent AMI (4–6 weeks)– Relative: epilepsy, closed-angle glaucoma, BPH, cardiorespiratory insufficiency, pheochromocytoma Pregnancy safety (except 1st trimester; doxepin discouraged in peripartum and lactation) |

| Amitriptyline (Deprelio®, Tryptizol®) | 10–150mg/day (night or divided in 2 doses)– Initial dose: 10–25mg/day– Increase by 10–25mg/day every 3–7 days if partial response | ||

| Nortriptyline (Martimil®, Paxtibi®) | 10–100mg/day– Initial dose: 10–20mg/day– Should be taken with meals | ||

| Clomipramine (Anafranil®) | 10–250mg/day (night or divided)– Initial dose: 10–25mg/day– Increase up to 100mg/day in first 2 weeks, then gradually if partial response | ||

| Imipramine (Tofranil®) | 10–200mg/day (1–3 divided doses)– Initial dose: 10–25mg/day– Increase to 150–200mg/day during first week, maintain until clinical improvement, then taper to maintenance 50–100mg/day | ||

| Others | |||

| Mirtazapine (Rexer®, Vastat®, Afloyan®) | 15–45mg/day (night)– Initial dose: 15–30mg/day– Increase to 45mg after 2–4 weeks if partial response | – Sedation– Weight gain– Hypercholesterolemia– Anticholinergic: xerostomia, constipation | Possible combination with other antidepressants:– Enhances antidepressant & anxiolytic effect– Good sleep regulator (may cause vivid dreams)– May improve GI tolerability of SSRIs Avoid alcohol Monitor weight closely |

| Bupropion (Elontril®) | 150–300mg/day (morning)– Initial: 150mg/day– Increase to 300mg/day at 4 weeks if partial response | – Insomnia– Headache– Decreased seizure threshold | Very low sexual side-effect burden Can be combined with SSRIs CYP2D6 inhibitor Also used for smoking cessation Contraindications: epilepsy history, alcohol/drug use |

| Vortioxetine (Brintellix®) | 5–20mg/day– Initial: 5mg/day first week, then 10mg/day– Increase to 15–20mg/day if partial response– Higher doses if significant anxiety | – Nausea, vomiting– Diarrhea– Headache– Xerostomia– Insomnia– Pruritus | Lower risk of sexual dysfunction vs SSRIs/SNRIs/TCAs Pro-cognitive effects in depression Does not alter QTc May cause pruritus in susceptible patients |

AMI: myocardial infarction; BPH: benign prostatic hyperplasia; ECG: electrocardiogram; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SNRI: serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant.

Dose ranges according to the prescribing information. Maximum doses based on Koran et al.50

Antidepressants are indicated for depressive syndromes, anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorders, and social phobia.4 In addition, they have demonstrated effectiveness in multiple psychodermatologic disorders, including cutaneous sensory disorders (psychogenic pruritus, dysesthesias, burning mouth syndrome, vulvodynia), dermatitis artefacta, and obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders (trichotillomania), although no specific antidepressant is uniquely indicated for each condition.4,7,8

In general, treatment should begin with low doses, progressively increasing until the optimal dose for each patient is reached.4 Therapeutic benefit is achieved after 2–4 weeks; however, if ineffective, switching to another agent should not be considered until after 6 weeks.4 Treatment should be maintained for at least 6 months after achieving clinical response to prevent early relapse.4,7 When discontinuing therapy, dose tapering is recommended to avoid withdrawal symptoms (flu-like symptoms, insomnia, nausea, instability).9

Adverse effects (AEs) vary among antidepressant classes, with tricyclic antidepressants having the least favorable safety and tolerability profile. Table 2 summarizes recommended doses and the main AEs of each drug.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)SSRIs increase synaptic serotonin levels by inhibiting its reuptake. They are considered first-line antidepressants due to their favorable tolerability and safety profile, especially escitalopram and sertraline. Escitalopram reduces both anxious–depressive symptoms and pruritus in patients with psoriasis.10 Other psychodermatologic conditions in which SSRIs have reported efficacy include burning mouth syndrome, excoriation disorder, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, and chronic pruritus.11–16

Unlike tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs have minimal antihistaminic, antiadrenergic, and anticholinergic activity, although some agents (e.g., paroxetine) may still exert these effects.17 The most common AEs are GI symptoms (nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, dyspepsia), usually mild and transient; other relatively frequent AEs include insomnia, emotional blunting (“apathy” or feeling “numb”), hyperhidrosis, and sexual dysfunction (anorgasmia or decreased libido), the latter being a common reason for treatment discontinuation.4

SSRIs are easy to use and considered safe during pregnancy, particularly sertraline; most guidelines recommend continuing the antidepressant that has been effective.18

Serotonin syndrome is a rare but potentially life-threatening AE and should be suspected in cases of overdose or drug interactions.19 It is characterized by the triad of altered mental status (agitation, hypervigilance), neuromuscular abnormalities (rigidity, tremor, myoclonus, hyperreflexia), and autonomic hyperactivity (tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, fever).20 Severe cases may lead to seizures, rhabdomyolysis, renal failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and even death.20

Withdrawal syndrome may occur, especially with paroxetine and fluvoxamine, due to their short half-life.7

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)Although used less frequently in dermatology than SSRIs, SNRIs (venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine) are particularly useful in patients with coexisting depression and anxiety because of their anxiolytic, antidepressant, and activating properties.7 They are a good alternative for patients with insufficient SSRI response and for individuals with predominant symptoms such as fatigue or pain.21 SNRIs have shown effectiveness in burning mouth syndrome, dermatitis artefacta, and body dysmorphic disorder.22,23

Their main AEs include headache, nausea, dizziness, asthenia, anxiety or nervousness, hyperhidrosis, xerostomia, constipation, and sleep disturbances (insomnia or somnolence).1,7,22 They may increase blood pressure, although the risk is low, particularly at standard therapeutic doses.24

Tricyclic antidepressantsTricyclic antidepressants are older agents that act by inhibiting the reuptake and increasing the synaptic levels of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine.25 Moreover, they block histaminergic, alpha-adrenergic, and muscarinic cholinergic receptors, accounting for many of their AEs.22 Their use has declined in favor of SSRIs and SNRIs due to inferior safety and multiple drug interactions. However, because of their antihistaminic properties, they remain useful in treating pruritus, urticaria, neuropathic pain, and insomnia, typically at doses lower than those used for depression.26 Doxepin, which has anti-H1 and anti-H2 activity, is the most widely used tricyclic in dermatology.27

AEs include xerostomia, blurred vision, constipation, urinary retention, glaucoma, dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia, sedation, and weight gain.4 Caution is advised in patients with cardiac disease, particularly conduction abnormalities or heart failure, and they are contraindicated in patients with recent myocardial infarction.22 Because they may cause electrocardiographic abnormalities, an ECG should be obtained before starting treatment and monitored during follow-up in women>40 years and men>30 years.4,22

Except for doxepin (contraindicated in the peripartum period and breastfeeding), tricyclics may be used during pregnancy, although initiation should be avoided in the first trimester.28 Nortriptyline is the safest agent within this class and is the preferred option for older adults.25

Other antidepressantsMirtazapineMirtazapine is a tetracyclic antidepressant that acts by blocking postsynaptic adrenergic (α2) and serotonergic (5-HT2, 5-HT3) receptors, thereby increasing the release of norepinephrine and serotonin.29 In dermatology, it is used for the management of pruritus—psychogenic or associated with dermatologic or systemic disease—and has shown effectiveness in pruritus related to malignancy, cholestasis, and renal failure.30 Its most relevant AEs include sedation, vivid dreams, increased appetite, weight gain, and, less commonly, anticholinergic effects.25 Due to its sedative action, it may be useful when combined with SSRIs in patients with insomnia or anxiety and may improve SSRI-related gastrointestinal intolerance through its 5-HT3 antagonism.21

BupropionBupropion is an antidepressant also used for smoking cessation. It is a selective inhibitor of norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake and additionally blocks nicotinic cholinergic receptors.31 It is generally well tolerated; AEs may include headache and insomnia. Because it lowers the seizure threshold, it should be avoided in patients with epilepsy or those who consume alcohol or other drugs.7 Its lower risk of sexual dysfunction makes it particularly useful in patients with antidepressant-induced libido impairment.31

VortioxetineVortioxetine, introduced in Spain in 2016, is a multimodal antidepressant: in addition to inhibiting serotonin reuptake, it acts on multiple pre- and postsynaptic serotonergic receptors and indirectly modulates noradrenergic, dopaminergic, cholinergic, and histaminergic systems.32 It has pro-cognitive properties and offers the most favorable sexual-side-effect profile among serotonergic modulators, making it a good alternative for patients who experience sexual dysfunction with SSRIs.33 A minority of individuals (1–10%) may develop pruritus with vortioxetine through unclear mechanisms.34

AntipsychoticsAntipsychotics (Table 3) are used to treat psychotic and delusional symptoms in conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and agitation. In dermatology, they may be used for somatic delusions (e.g., delusional infestation, delusional dysmorphia), factitious disorders, and body-focused repetitive behaviors (trichotillomania, excoriation disorder).35,36 Due to their broad receptor profile, they are also beneficial in treating pruritus and even hyperhidrosis.37 Their use is more complex than that of antidepressants due to their AE profile.

Main antipsychotics in dermatology.

| Drug | Dose | AEs | Other notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical antipsychotics | |||

| Pimozide (Orap®) | 2–12mg/day (morning)– Initial dose: 1mg/day– Increase by 1mg/day every 2 weeks if partial response | – Antidopaminergic (++): extrapyramidal symptoms (dystonia, akathisia, parkinsonism, dyskinesias)– Hyperprolactinemia: galactorrhea, sexual dysfunction, amenorrhea– Antihistaminergic: weight gain, sedation– Antiadrenergic: orthostatic hypotension– Anticholinergic: xerostomia, blurry vision, constipation, urinary retention, glaucoma– ECG disturbance (++): QT prolongation– Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | Avoid in patients with arrhythmia or QT prolongation Avoid in Parkinson's disease |

| Atypical antipsychotics | |||

| Risperidone (Arketin®, Calmapride®, Diaforin®, Rispemylan®, Risperdal®) | 2–6mg/day (night)– Initial dose: 0.5mg/day– Increase weekly if partial response | – Hyperprolactinemia (++): galactorrhea, sexual dysfunction, amenorrhea– Extrapyramidal symptoms– ECG changes | Most incisive atypical antipsychotic (strong D2 antagonism) and highest rate of extrapyramidal effects among atypicals |

| Olanzapine (Arenbil®, Zapris®, Zolafren®, Zyprexa®) | 5–20mg/day– Initial dose: 5–10mg/day– Increase if partial response | – Metabolic syndrome (++)– Weight gain (++)– Sedation (++)– Hyperprolactinemia: galactorrhea, sexual dysfunction, amenorrhea– Anticholinergic: xerostomia, blurry vision, constipation, urinary retention, glaucoma | Strong sedative and anxiolytic effects Monitor blood glucose, lipid profile, BP, and weight |

| Quetiapine (Seroquel®, Seroquel Prolong®) | 25–750mg every 12h– Initial dose: 25mg/12h– Gradually increase to target dose over days or weeks (50→100→200→300), slower titration if sedation is undesirable– Doses 100–300mg/day often sufficient for anxiety and psychosomatic symptoms | – Metabolic syndrome (+)– Weight gain (+)– Sedation (+)– Anticholinergic: xerostomia, blurry vision, constipation, urinary retention, glaucoma– Antiadrenergic: orthostatic hypotension– Cataracts | Strong sedative and anxiolytic effects Extended-release form is less sedating and can be taken once daily Monitor blood glucose, lipid profile, BP, and weight |

| Paliperidone | 3–12mg/day– Initial dose: 3mg/day | – Similar profile to risperidone (especially at higher doses) | Principal active metabolite of risperidone More incisive than other atypical antipsychotics |

| Ziprasidone (Zeldox®) | 20–80mg every 12h– Initial dose: 40mg/12h– Must be taken with food | – ECG changes: QT prolongation | Lower risk of adverse events (metabolic syndrome, weight gain, anticholinergic effects, extrapyramidal symptoms, hyperprolactinemia) |

| Aripiprazole (Abilify®, Aristada®) | 10–30mg/day– Initial dose: 10–15mg/day | – Akathisia | |

Dose ranges follow product information.

Recently introduced antipsychotics such as cariprazine, lurasidone, and brexpiprazole are not included due to limited experience in psychodermatology.

Antipsychotics are dopamine D2-receptor antagonists and exert their antipsychotic effect through actions on the mesocorticolimbic pathway.4 However, dopaminergic blockade in other pathways of the central nervous system (CNS) leads to the most well-known adverse effects (AEs). Extrapyramidal motor symptoms—such as dystonia, akathisia, parkinsonism, and dyskinesia—result from blockade of the nigrostriatal pathway, while blockade of the tuberoinfundibular pathway interferes with prolactin regulation, leading to galactorrhea, sexual dysfunction, and amenorrhea.38 In addition, blockade of other receptor types can produce various AEs: weight gain and sedation (via histaminergic blockade), orthostatic hypotension (via α-adrenergic blockade), and anticholinergic symptoms (via muscarinic receptor blockade).38 Cardiac effects may include electrocardiographic abnormalities (such as QT prolongation) and increased risk of acute myocardial infarction.38 One of the most serious AEs is neuroleptic malignant syndrome, which presents with fever, muscle rigidity, confusion, tachycardia, and arrhythmias.38

Antipsychotics are classified into first-generation (“typical”) agents (e.g., haloperidol, pimozide, chlorpromazine) and second-generation (“atypical”) agents (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, sulpiride, risperidone, paliperidone). Newer third-generation antipsychotics (e.g., aripiprazole, cariprazine, brexpiprazole, lurasidone) have more nuanced partial agonist/antagonist activity at dopaminergic and serotonergic receptors. Atypical antipsychotics have lower affinity for D2 receptors (except risperidone) and antagonize 5-HT2A receptors, resulting in fewer extrapyramidal symptoms.38 However, they carry a higher risk of metabolic AEs (weight gain, diabetes, dyslipidemia).38 Overall, atypical antipsychotics are preferred, particularly risperidone and aripiprazole (the best tolerated). Quetiapine and olanzapine may be useful when sedation is desired in patients with prominent anxiety. Third-generation antipsychotics are characterized by being partial dopaminergic and/or serotonergic agonists or antagonists.

It is recommended to start the drug at low doses (even at half or one-quarter of the usual dose in older adults), increase gradually every 4 weeks depending on the response, and once effectiveness is achieved, maintain treatment for 3–6 months before tapering.7 Antipsychotics should be avoided during pregnancy, particularly in the first trimester due to their potential teratogenicity; if required, haloperidol is the agent with the most experience in pregnant patients.1,4

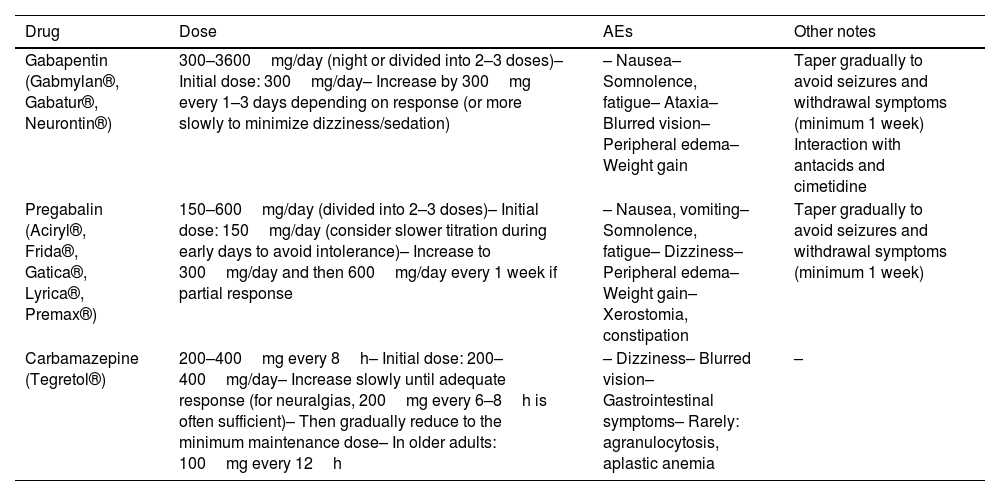

AnticonvulsantsAnticonvulsants (Table 4) are used to treat epilepsy and bipolar disorder, but in psychodermatology they have multiple applications, particularly for neuropathic pain (e.g., postherpetic neuralgia, notalgia paresthetica), allodynia, cutaneous sensory syndromes linked to CNS sensitization, and chronic pruritus.39–43 They have also demonstrated benefit in self-inflicted dermatoses due to their effects on impulse regulation, including excoriation disorder, prurigo nodularis, lichen simplex chronicus, trichotillomania, and dermatitis artefacta.39 Symptoms of autonomic hyperarousal—such as facial flushing, hyperhidrosis, and urticaria—may also respond to these drugs.39

Main anticonvulsants in dermatology.

| Drug | Dose | AEs | Other notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gabapentin (Gabmylan®, Gabatur®, Neurontin®) | 300–3600mg/day (night or divided into 2–3 doses)– Initial dose: 300mg/day– Increase by 300mg every 1–3 days depending on response (or more slowly to minimize dizziness/sedation) | – Nausea– Somnolence, fatigue– Ataxia– Blurred vision– Peripheral edema– Weight gain | Taper gradually to avoid seizures and withdrawal symptoms (minimum 1 week) Interaction with antacids and cimetidine |

| Pregabalin (Aciryl®, Frida®, Gatica®, Lyrica®, Premax®) | 150–600mg/day (divided into 2–3 doses)– Initial dose: 150mg/day (consider slower titration during early days to avoid intolerance)– Increase to 300mg/day and then 600mg/day every 1 week if partial response | – Nausea, vomiting– Somnolence, fatigue– Dizziness– Peripheral edema– Weight gain– Xerostomia, constipation | Taper gradually to avoid seizures and withdrawal symptoms (minimum 1 week) |

| Carbamazepine (Tegretol®) | 200–400mg every 8h– Initial dose: 200–400mg/day– Increase slowly until adequate response (for neuralgias, 200mg every 6–8h is often sufficient)– Then gradually reduce to the minimum maintenance dose– In older adults: 100mg every 12h | – Dizziness– Blurred vision– Gastrointestinal symptoms– Rarely: agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia | – |

They are generally well tolerated, have favorable safety profiles, and few drug interactions.22 They should be avoided during pregnancy due to teratogenicity.4

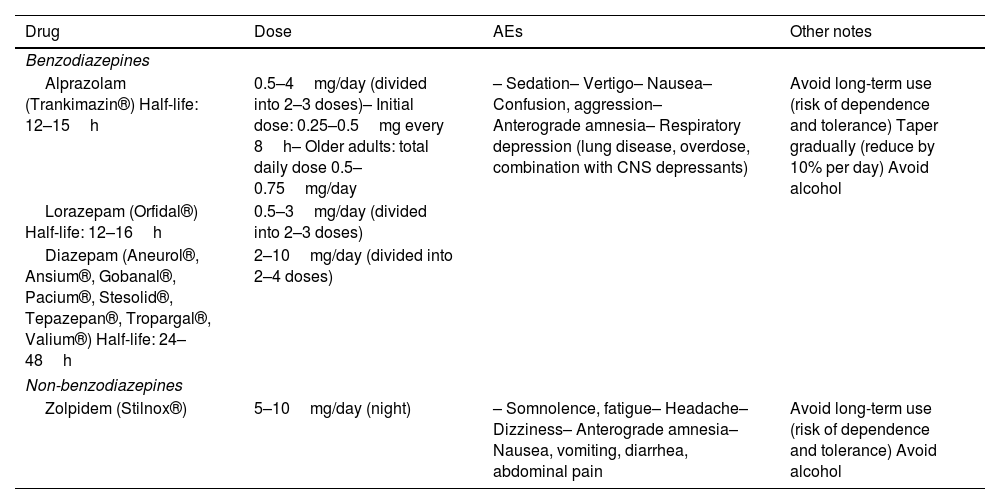

AnxiolyticsAnxiolytics (Table 5) are used to rapidly alleviate anxiety symptoms, typically in combination with antidepressants until the latter achieve sustained effect. They are used for depressive disorders with anxious or insomnia-related symptoms, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders, and somatoform disorders. In psychodermatology, they are valuable for managing anxiety and social phobia symptoms related to chronic or disfiguring dermatoses.7

Main anxiolytics in dermatology.

| Drug | Dose | AEs | Other notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines | |||

| Alprazolam (Trankimazin®) Half-life: 12–15h | 0.5–4mg/day (divided into 2–3 doses)– Initial dose: 0.25–0.5mg every 8h– Older adults: total daily dose 0.5–0.75mg/day | – Sedation– Vertigo– Nausea– Confusion, aggression– Anterograde amnesia– Respiratory depression (lung disease, overdose, combination with CNS depressants) | Avoid long-term use (risk of dependence and tolerance) Taper gradually (reduce by 10% per day) Avoid alcohol |

| Lorazepam (Orfidal®) Half-life: 12–16h | 0.5–3mg/day (divided into 2–3 doses) | ||

| Diazepam (Aneurol®, Ansium®, Gobanal®, Pacium®, Stesolid®, Tepazepan®, Tropargal®, Valium®) Half-life: 24–48h | 2–10mg/day (divided into 2–4 doses) | ||

| Non-benzodiazepines | |||

| Zolpidem (Stilnox®) | 5–10mg/day (night) | – Somnolence, fatigue– Headache– Dizziness– Anterograde amnesia– Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain | Avoid long-term use (risk of dependence and tolerance) Avoid alcohol |

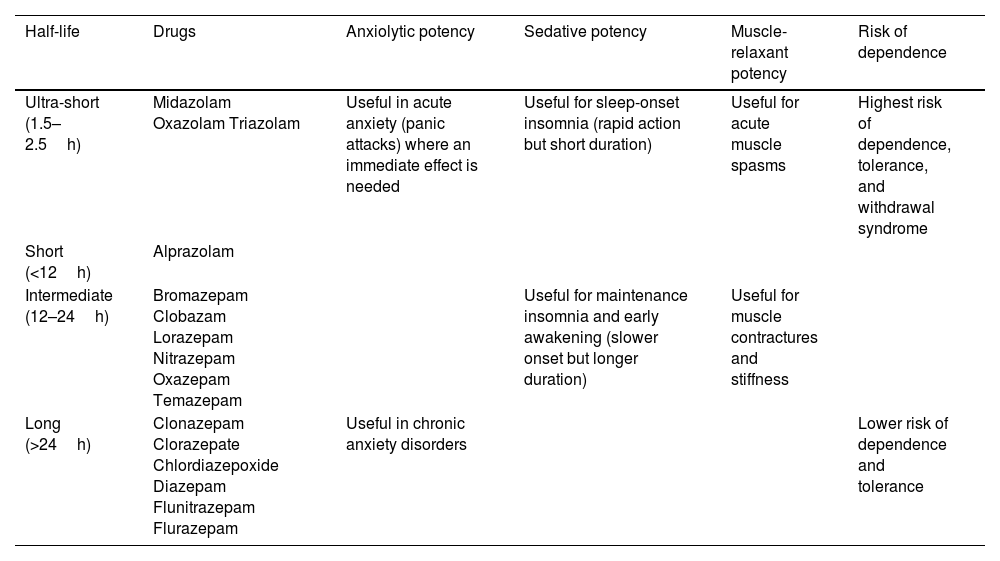

The most widely used agents are benzodiazepines, which act on γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-dependent chloride channels to enhance CNS inhibition.44 They have potent anxiolytic, sedative-hypnotic, muscle-relaxant, and anticonvulsant properties.45 They are classified by half-life, which determines their pharmacologic profile (Table 6). Because they may cause tolerance and dependence, their long-term use should be limited (ideally 3–4 weeks, or up to 8–12 weeks for longer-acting agents).7,45 Scheduled dosing is preferred over PRN use to reduce abuse risk. If long-term therapy is anticipated, antidepressants should be introduced and benzodiazepines tapered slowly.

Classification and action profile of benzodiazepines according to half-life.

| Half-life | Drugs | Anxiolytic potency | Sedative potency | Muscle-relaxant potency | Risk of dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-short (1.5–2.5h) | Midazolam Oxazolam Triazolam | Useful in acute anxiety (panic attacks) where an immediate effect is needed | Useful for sleep-onset insomnia (rapid action but short duration) | Useful for acute muscle spasms | Highest risk of dependence, tolerance, and withdrawal syndrome |

| Short (<12h) | Alprazolam | ||||

| Intermediate (12–24h) | Bromazepam Clobazam Lorazepam Nitrazepam Oxazepam Temazepam | Useful for maintenance insomnia and early awakening (slower onset but longer duration) | Useful for muscle contractures and stiffness | ||

| Long (>24h) | Clonazepam Clorazepate Chlordiazepoxide Diazepam Flunitrazepam Flurazepam | Useful in chronic anxiety disorders | Lower risk of dependence and tolerance |

The most common AEs include sedation (which is why nighttime administration is recommended), dizziness, nausea, confusion, aggression, anterograde amnesia, and difficulty with learning.44 Most of these AEs improve over time or with dose reduction. They may cause respiratory depression in patients with chronic lung disease and in cases of overdose or when combined with other central nervous system depressants, such as alcohol.44 Gradual tapering is recommended (approximately 10% of the dose per day) to prevent withdrawal symptoms, such as anxiety, instability, sweating, palpitations, nausea, confusion, and, rarely, seizures.7 Their use should be avoided during the first trimester of pregnancy.22

Other non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics include zolpidem (a benzodiazepine-like hypnotic primarily used as a sleep inducer) and buspirone (a slow-acting anxiolytic, no longer marketed in Spain).

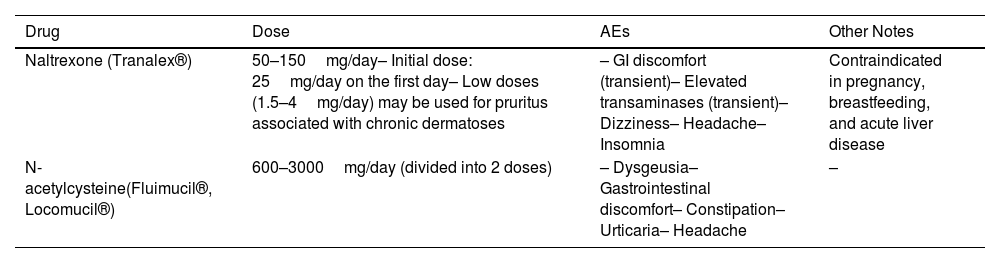

Miscellaneous agentsNaltrexoneNaltrexone is an opioid antagonist used for opioid and alcohol dependence.7 In psychodermatology, it is effective for pruritus—particularly psychogenic and cholestatic—but also in refractory pruritus associated with inflammatory dermatoses such as lichen planopilaris.46 Low doses (1.5–4mg/day) appear more effective for chronic dermatosis-associated pruritus than standard doses.46 It may also provide benefit in trichotillomania and excoriation disorder.47

Naltrexone has a favorable safety profile (Table 7) and does not cause dependence or tolerance.22 It is contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation.22

Other drugs used in psychodermatology.

| Drug | Dose | AEs | Other Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naltrexone (Tranalex®) | 50–150mg/day– Initial dose: 25mg/day on the first day– Low doses (1.5–4mg/day) may be used for pruritus associated with chronic dermatoses | – GI discomfort (transient)– Elevated transaminases (transient)– Dizziness– Headache– Insomnia | Contraindicated in pregnancy, breastfeeding, and acute liver disease |

| N-acetylcysteine(Fluimucil®, Locomucil®) | 600–3000mg/day (divided into 2 doses) | – Dysgeusia– Gastrointestinal discomfort– Constipation– Urticaria– Headache | – |

N-acetylcysteine is a precursor of l-cysteine, traditionally used as a mucolytic agent. It modulates glutamate and dopamine levels and has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.48 It is used for body-focused repetitive behaviors, including trichotillomania, trichoteiromania, onychotillomania, onychophagia, and excoriation disorder.49

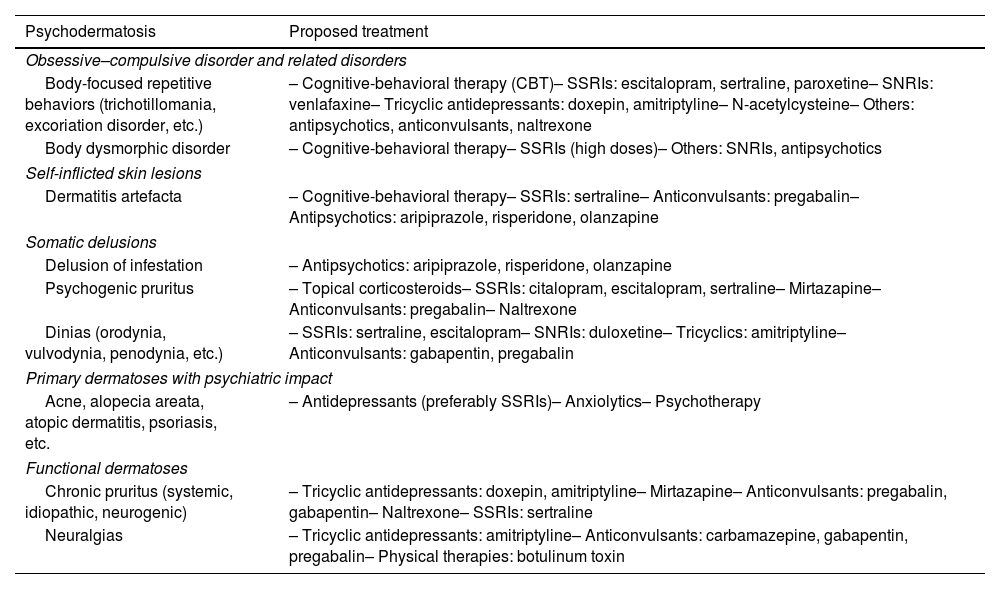

First-line treatments in psychodermatologyTable 8 illustrates key psychodermatoses and corresponding therapeutic recommendations.

Recommended treatments by type of psychodermatosis.22,46,49,51–57

| Psychodermatosis | Proposed treatment |

|---|---|

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder and related disorders | |

| Body-focused repetitive behaviors (trichotillomania, excoriation disorder, etc.) | – Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)– SSRIs: escitalopram, sertraline, paroxetine– SNRIs: venlafaxine– Tricyclic antidepressants: doxepin, amitriptyline– N-acetylcysteine– Others: antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, naltrexone |

| Body dysmorphic disorder | – Cognitive-behavioral therapy– SSRIs (high doses)– Others: SNRIs, antipsychotics |

| Self-inflicted skin lesions | |

| Dermatitis artefacta | – Cognitive-behavioral therapy– SSRIs: sertraline– Anticonvulsants: pregabalin– Antipsychotics: aripiprazole, risperidone, olanzapine |

| Somatic delusions | |

| Delusion of infestation | – Antipsychotics: aripiprazole, risperidone, olanzapine |

| Psychogenic pruritus | – Topical corticosteroids– SSRIs: citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline– Mirtazapine– Anticonvulsants: pregabalin– Naltrexone |

| Dinias (orodynia, vulvodynia, penodynia, etc.) | – SSRIs: sertraline, escitalopram– SNRIs: duloxetine– Tricyclics: amitriptyline– Anticonvulsants: gabapentin, pregabalin |

| Primary dermatoses with psychiatric impact | |

| Acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, etc. | – Antidepressants (preferably SSRIs)– Anxiolytics– Psychotherapy |

| Functional dermatoses | |

| Chronic pruritus (systemic, idiopathic, neurogenic) | – Tricyclic antidepressants: doxepin, amitriptyline– Mirtazapine– Anticonvulsants: pregabalin, gabapentin– Naltrexone– SSRIs: sertraline |

| Neuralgias | – Tricyclic antidepressants: amitriptyline– Anticonvulsants: carbamazepine, gabapentin, pregabalin– Physical therapies: botulinum toxin |

SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SNRI: serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

Recommendations based on the literature described in the reference article and the authors’ own experience.

Psychiatric comorbidity is highly prevalent among dermatology patients. Establishing a strong therapeutic alliance through empathetic communication facilitates exploration of psychodermatologic symptoms, improves patient satisfaction, enhances adherence, and optimizes clinical outcomes. Dermatologists should be able to identify these conditions and understand the mechanisms of action, indications, and adverse-effect profiles of relevant psychotropic drugs to contribute to holistic dermatologic care. Encouraging patients to seek psychotherapeutic and psychiatric support when needed is equally essential.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.