This study aims to present an interim analysis of safety data from the Spanish cohort of the NISSO post-authorization safety study on the long-term tolerability of sonidegib in patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma (laBCC).

MethodsNISSO is a non-interventional, multinational, post-authorization safety study (NCT04066504). Patients with laBCC were administered sonidegib 200mg/day and monitored for 3 years. Dose adjustments were permitted according to the Spanish prescribing information.

ResultsBetween January 8th, 2021, and March 7th, 2022, a total of 51 patients with laBCC were enrolled in the study in Spain (data cut June 22nd, 2023). Treatment was discontinued in 39 patients (76.5%), primarily due to treatment success (n=11, 21.6%), patient or guardian decision (n=8, 15.7%), and physician decision (n=8, 15.7%). The median duration of exposure was 6.5 months (IQR, 5.69–11.91 months). A total of 45 (88.2%) patients experienced at least one treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE). The most common TEAEs were muscle spasms (n=23, 45.1%), alopecia (n=23, 45.1%), and dysgeusia (n=23, 45.1%). Cumulative rates of the above-mentioned TEAEs at 3 months were 27.5%, 11.8%, and 29.4%, respectively. Most TEAEs were grade≤2. TEAEs led to treatment discontinuation in 10 patients (19.6%), while 8 (15.7%) required dose modifications due to adverse events. Serious drug-related TEAEs were reported in 2 patients (3.9%).

ConclusionsMost patients experienced grade≤2 common TEAEs, such as muscle spasms, dysgeusia, and alopecia that mostly manifested 3 months into therapy. These interim results confirm the safety profile observed in the BOLT study, demonstrating that sonidegib is well-tolerated in a real-world setting in Spain.

Skin cancer is the most prevalent type of malignancy in Western countries.1 Among these, non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) is the most common, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma accounting for 70% and 25%, respectively in the European population.1 In Spain, a systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that the incidence rate of BCC is approximately 113.05 per 100,000 person-years,2 and an ecological study found that the standardized mortality rate of NMSC during the 2015–2019 period was 1.25.3

Although BCC has a low likelihood of metastasis, it is a slow-progressing tumor that leads to morbidity because of its usual closeness to vital facial structures, affecting the patients’ quality of life.4 BCC may relapse, manifest in multiple locations, and invade or destroy local tissues.4 Surgical excision and radiotherapy are the primary treatments, offering cure rates of more than 95% and up to 90%, respectively.4 However, some BCCs progress to an advanced stage where surgery and radiotherapy are no longer curative options.

Advanced BCC includes locally advanced BCC (laBCC) and metastatic BCC (mBCC). Mutations resulting in aberrant activation of the Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway—most frequently in the human homolog of the Drosophila gene patched (PTCH1, ∼73%), and less commonly in smoothened (SMO, ∼20%) and suppressor of fused (SUFU, ∼8%)—have been identified in patients with Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome) and in more than 95% of sporadic BCC cases.5 Consequently, recent research has focused on developing therapeutic strategies to deactivate the Hh signaling pathway by inhibiting the SMO receptor.5 This has led to the approval of 2 Hh pathway inhibitors (HHIs): vismodegib and sonidegib.5 These 2 drugs are specific inhibitors of the smoothened protein in the Hh signaling pathway and have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for treating patients with laBCC who are ineligible for surgery or radiotherapy.6 Furthermore, vismodegib has also approved for mBCC, and sonidegib for mBCC only in both Switzerland and Australia.

The safety and efficacy profile of sonidegib in Europe were initially observed in the pivotal Phase 2 BOLT trial (Basal Cell Carcinoma Outcomes with LDE225 Treatment).7 Subsequently, the NISSO study (NCT04066504), a postauthorization safety study designed to collect real-world, long-term safety data on the use of sonidegib in this patient population, was conducted.8 The present study provides a preliminary analysis of safety data from the Spanish cohort of the NISSO postauthorization safety study, which evaluates the long-term tolerability of sonidegib in patients with laBCC. The secondary endpoint was to describe treatment regimens administered after drug discontinuation.

Material and methodsPatientsThe ongoing NISSO study (PASS; NCT04066504) is a noninterventional, multinational, postauthorization safety study enrolling patients aged ≥18 years with laBCC who are ineligible for curative surgery or radiation therapy. Participants received oral sonidegib 200mg once daily, with dose adjustments made according to the prescribing information approved in Spain.

Treatment with sonidegib could be initiated prior to study enrollment. Patients with Gorlin syndrome were eligible if they met all inclusion criteria, whereas those who had received any hedgehog pathway inhibitor other than sonidegib within 3 months before enrollment were excluded. Participants were followed for 3 years after enrollment. The study population included all patients who received at least 1 dose of sonidegib.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the participant centers in full compliance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All participants gave their prior written informed consent.

VariablesDemographic and clinical data collected included age, gender, Gorlin syndrome, primary tumor location, laBCC histotype, and the largest diameter of the primary tumor, as well as details of previous treatments. The duration of sonidegib treatment and therapy after its conclusion were also collected.

The safety evaluation focused on adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), along with any discontinuations or dose reductions during treatment.

StatisticsCategorical data were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages, and continuous variables expressed as medians, range, and interquartile range (IQR). Calculations were based on the available values. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States).

ResultsPopulationBetween January 8th, 2021, and March 7th, 2022, a total of 51 patients with laBCC were enrolled (data cut June 22nd, 2023). Table 1 illustrates the baseline demographics and characteristics. The median age of the study population was 81 years (56.9% men and 11.8% affected by the Gorlin syndrome). Prior to sonidegib, 47.1%, 13.7% and 21.6% of patients received surgery, radiotherapy and systemic therapy (mostly vismodegib), respectively. The median duration of sonidegib treatment was 6.5 months [IQR, 5.7–11.9 months].

Baseline demographics and characteristics.

| N=51 | |

|---|---|

| Age, years, median (SD) | 81 (35–96) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 29 (56.9) |

| Female | 22 (43.1) |

| Gorlin syndrome, n (%) | 6 (11.8) |

| Primary tumor location, n (%) | |

| Head | 34 (66.67) |

| Neck | 1 (1.96) |

| Feet | 1 (1.96) |

| Other | 12 (23.53) |

| Unknown | 3 (5.88) |

| LaBCC histotype (multiple answers possible), n (%) | |

| Superficial | 1 (1.96) |

| Nodular | 13 (25.49) |

| Micronodular | 3 (5.88) |

| Infiltrative | 27 (52.94) |

| Morpheaform | 1 (1.96) |

| Basosquamous | 1 (1.96) |

| Other | 1 (1.96) |

| Unknown | 8 (15.69) |

| Largest diameter of primary tumor, mm, median (range) | 30.0 (3.00–150.0) |

| Prior radiotherapy, n (%) | 7 (13.73) |

| Prior surgery, n (%) | 24 (47.06) |

| Prior local therapies, n (%) | 8 (15.69) |

| Prior systemic therapies, n (%) | 11 (21.57) |

| Vismodegib | 10 (19.61) |

| Immunotherapy | 1 (1.96) |

| Cemiplimab | 1 (1.96) |

| Sonidegib treatment duration median, months (IQR) | 6.5 (5.69–11.91) |

IQR: interquartile range; LaBCC: locally advanced basal cell carcinoma.

Overall, 45 (88.2%) patients had ≥1 TEAE (Table 2). The TEAE were considered drug-related in 80.4% of patients (n=41). TEAE led to treatment discontinuation, dose reduction, and discontinuation in 10 (19.6%), 9 (17.6%), and 3 (5.9%) patients, respectively (Table 2). Serious TEAEs were reported in 9 (17.6%) patients. The serious TEAE were considered drug-related in 3.92% of patients (n=2; Table 2).

Overview of TEAE.

| N=51 | |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Patients with TEAE | 45 (88.24) |

| Patients with drug-related TEAE | 41 (80.39) |

| Patients with TEAE leading to deatha | 3 (5.88) |

| Patients with TEAE leading to discontinuation of sonidegib | 10 (19.61) |

| Patients with TEAE leading to dose reduction | 9 (17.65) |

| Patients with TEAE leading to discontinuation | 3 (5.88) |

| Patients with serious TEAE | 9 (17.65) |

| Patients with serious drug-related TEAEb | 2 (3.92) |

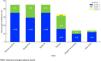

Fig. 1 illustrates the incidence rate of common TEAEs (those occurring in ≥10% patients, by severity). More than half (51.0%) of the patients experienced nervous system disorders, with dysgeusia occurring frequently (29.4%, grade 1; 15.7%, grade 2). Musculoskeletal disorders were observed in nearly half of the patients (49.0%) predominantly, muscle spasms (35.3%, grade 1; 9.8%, grade 2). A significant proportion of patients (47.1%) reported skin-related issues, particularly alopecia (35.3%, grade 1; 9.8%, grade 2). Other notable TEAEs included fatigue (15.7%, grade 1; 15.7%, grade 2; 2.0%, grade 3), diarrhea (11.8%, grade 1; 2.0%, grade 2), nausea (3.9%, grade 1; 2.0%, grade 2), and decreased weight (9.8%, grade 1; 3.9%, grade 2).

Additionally, SAEs were reported, including cardiac disorders, infections, and 1 death, considered not drug-related by investigator.

Fig. 2 illustrates the Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the most common TEAEs, including fatigue, alopecia, dysgeusia, and muscle spasms. Most of these adverse events occurred primarily within the first year, after which their incidence rate tended to stabilize. By approximately 24 months, the survival probabilities for all TEAEs stabilized, with values ranging approximately between 9% and 40%.

The related data to treatment discontinuation and dose reduction is shown in Table 3. Overall, 15 (29.4%) patients experienced at least 1 therapy discontinuation, with a median duration of treatment discontinuation of 32 days. The median number of treatment discontinuations was 1. The reasons for treatment discontinuations included AEs in 2 (3.9%) patients, SAEs in 1 (2.9%) patient, patient’ decision in 3 (5.9%) cases, tumor progression in 2 (3.9%) patients, complete response/achieved therapy goal in 2 (3.9%) patients, unavailability of care/drug in 2 (3.9%) patients, and decision of the physician in 3 (5.9%) patients.

Discontinuations and dose reductions.

| N=51 | |

|---|---|

| Median duration of treatment discontinuation, days (range) | 32 (1–358) |

| No. of patients with at least one therapy discontinuation, n (%) | 15 (29.41) |

| No. of therapy discontinuations, median (range) | 1 (1–2) |

| Reasons for therapy discontinuation, n (%) | |

| AE | 2 (3.92) |

| Serious AE | 1 (1.96) |

| Patient's wish | 3 (5.88) |

| Tumor progression | 2 (3.92) |

| Complete response/achieved therapy goal | 2 (3.92) |

| (Un)Availability of care/drug | 2 (3.92) |

| Physicians’ decision | 3 (5.88) |

| No. of patients with at least one dose reduction, n (%) | 15 (29.41) |

| No. of dose reductions, median (range) | 1 (1–2) |

| Reasons for dose reduction, n (%) | |

| AE | 8 (15.69) |

| Serious AE | 1 (1.96) |

| Patient's wish | 2 (3.92) |

| Tumor progression | 2 (3.92) |

| Complete response/achieved therapy goal | 1 (1.96) |

| (Un)Availability of care/drug | 1 (1.96) |

| Physicians’ decision | 1 (7.84) |

AE: adverse event.

Additionally, 15 patients (29.4%) required at least 1 dose reduction, with a median of 1 dose reduction (range, 1–2). The reasons for dose reduction were AEs in 8 patients (15.7%), a SAEs in 1 patient (2.0%), patient preference in 2 patients (3.9%), tumor progression in 5 patients (9.8%), complete response or achievement of therapeutic goal in 1 patient (2.0%), lack of care or drug availability in 1 patient (2.0%), and physician decision in 4 patients (7.8%).

The related data for further antineoplastic laBCC treatment after the completion of sonidegib treatment is shown in Supplementary Table 1. A total of 7 (13.7%) patients received further antineoplastic laBCC treatment. Among these, 1 (2.0%) patient received radiotherapy. Surgery was performed in 3 (5.9%) patients, all of which were localized to the head. Regarding the type of surgery, 1 (2.0%) patient underwent conventional surgery, and 2 (3.9%) patients, Mohs surgery. The percentage resection status among these patients was the same with R0 resection achieved in 1 (2.0%) patient, R1 resection in 1 (2.0%) patient, and R2 resection in 1 (2.0%) patient. Systemic therapy was administered to 3 (5.9%) patients. Within this group, 1 (2.0%) patient received another form of systemic therapy, and 2 (3.9%) patients received immunotherapy. Specifically, nivolumab was used in 1 patient (2.0%), and pembrolizumab in 2 patients (3.9%; 1 patient received both immunotherapies).

DiscussionThis interim analysis of the NISSO post-marketing safety observational study based in Spain contributes valuable data to the growing body of real-world evidence on the use of HHIs in the Spanish health care system, specifically focusing on sonidegib.9–11

Before comparing the findings of the present study with those of the BOLT pivotal trial, it is important to acknowledge both the similarities and differences in baseline demographic characteristics between the cohorts.7 The median age in the Spanish cohort was significantly higher (81 vs 67 years), suggesting a different risk profile and comorbidity burden that could influence treatment outcomes and the safety profile of sonidegib. Additionally, fewer Spanish patients had prior surgery or radiotherapy (41.7% and 13.7%, respectively) vs the BOLT trial (76% and 32%).7 This reflects updated European clinical practice guidelines, which introduced the EADO classification and expanded HHI eligibility to include Stage II and III patients ineligible for surgery or radiotherapy, such as those with inoperable Gorlin syndrome.12 Furthermore, the BOLT trial excluded patients previously treated with systemic HHIs, whereas 20% of the Spanish cohort had prior vismodegib treatment, which is consistent with other real-world Spanish studies.7

After addressing the demographic differences, it is now appropriate to compare the safety data between the 2 studies. Similarly to the BOLT trial, most TEAEs in the NISSO study were mild or moderate in severity. The proportion of patients experiencing serious TEAEs was comparable to that observed in the BOLT study. Common TEAEs in the NISSO Spanish cohort included muscle spasms, alopecia, dysgeusia, decreased weight, decreased appetite, diarrhea, fatigue, and nausea. Compared with the BOLT data, the incidence rate of dysgeusia and fatigue was similar,7 while the other common TEAEs occurred in fewer patients in the NISSO Spanish cohort. The most common TEAEs linked to Hh pathway inhibition occur with both sonidegib and vismodegib. Clinical trial data, despite indirect comparison limitations, suggest sonidegib has approximately a 10% lower incidence rate, later onset, and milder severity than vismodegib (BOLT, ERIVANCE trials).7,13,14 A post-authorization safety study on vismodegib is lacking. The STEVIE study,15 which assessed vismodegib in a real-world-like population, provides a basis for comparison with NISSO data. TEAE incidence rate was lower in the NISSO Spanish cohort, particularly for muscle spasms (43.1% vs 66%), alopecia (41.2% vs 62%), dysgeusia (45.1% vs 55%), and weight loss (13.7% vs 41%).15 Nausea was less frequent in the NISSO Spanish cohort (5.9%) than in the STEVIE study (17.9%), whereas diarrhea occurred in 13.7% of patients vs 16.2% in STEVIE. Fatigue, however, was slightly more common in NISSO (29.4% vs 16.5%).15 Overall, the NISSO Spanish cohort demonstrated a more manageable TEAE profile than STEVIE, although certain differences should be taken into consideration. The mean age in the NISSO cohort was approximately 11 years higher, the median treatment duration in STEVIE was slightly longer (by about 2 months), and STEVIE included a subset of patients with metastatic BCC (7.9%), whereas the NISSO study exclusively enrolled patients with laBCC.15 Additionally, STEVIE had a larger population vs the NISSO Spanish cohort. While these differences must be considered, the real-world data appear to align with the safety conclusions of the pivotal studies, which showed that sonidegib was associated with slightly less frequent and less severe common AEs vs vismodegib at the final analyses.14,16 A plausible explanation for these differences could lie in the distinct pharmacokinetic profiles of the two HHIs. Evidence suggests that sonidegib has better tissue distribution and higher lipophilicity, with its concentration in the skin being 6 times greater than in plasma.17,18 This may account for the observed variations in toxicity and efficacy between the 2 HHIs.16

Compared with the BOLT trial, the proportion of patients with TEAEs leading to discontinuation of sonidegib was lower in this study, while the data on dose reductions and treatment discontinuations were consistent with those reported in the BOLT trial.7 In this study, the primary reason for dose reductions was adverse events, a strategy that has been explored in other publications and endorsed for managing all related HHI toxicities in a consensus article.19 Additionally, alternative approaches to managing adverse events with sonidegib are being investigated, such as the use of calcium, with or without Coenzyme Q10 supplementation to reduce the need for dose reductions due to HHI associated muscle spasms, thereby enabling patients to remain on therapy longer.20 However, more data is needed before this approach can be widely adopted as a standard protocol.

Of note, key differences between the Spanish cohort and the overall NISSO population.8 For example, the median treatment duration was shorter in the Spanish cohort (6.5 vs 8.8 months), and fewer dose changes were reported (15.7% vs 46.4%, respectively). Despite the shorter exposure, the frequency of common AEs—such as muscle spasms, alopecia, and dysgeusia—was slightly higher in the Spanish cohort. This difference may be explained by the older median age of the Spanish population (81 vs 77 years) and potential variations in clinical practice. To support a comprehensive comparison, a summary table is provided outlining key safety and demographic data from the NISSO study (Spanish and global cohorts)8 and from the pivotal BOLT and STEVIE trials (Supplementary Table 2).7,15

As observed in the presented data, in clinical practice, some patients who discontinue HHI may be reassessed for surgical removal if their tumor becomes operable, or they may resume HHI treatment later. Others might transition to immunotherapy, depending on the reason the HHI was stopped.20 In this study, about 18% of the patients who stopped sonidegib for reasons other than complete response, death or loss to follow-up received additional treatments for laBCC, including systemic therapy, surgery, and radiotherapy. Systemic therapy included immunotherapy with nivolumab and pembrolizumab, both monoclonal antibodies targeting the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor on T-cells.20 Interestingly, evidence suggests that HHI treatment before immunotherapy may enhance tumor responsiveness to anti-PD-1 therapy.20 Currently, patients can access the approved anti PD-1 second-line therapy if they experience disease progression during HHI therapy (due to primary or secondary resistance) or if they continue to face persistent toxicity despite prolonged efforts to manage AEs.21

Regarding surgery, it was the second most common treatment following sonidegib and is supported by evidence of significant tumor shrinkage observed in key trials after HHI therapy. Initial data from the VISMONEO trial, a multicenter, open-label, phase 2 study, indicated that neoadjuvant vismodegib enabled downstaging of surgical procedures for laBCC in functionally sensitive locations.22 Additionally, a recent study reported two patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma of the face achieving complete remission with sonidegib, allowing for less extensive surgical excision than would have been required without targeted therapy.23 A trial is underway evaluating the use of radiotherapy after complete response with HHIs as a consolidation therapy (NCT05561634).

Although not the primary endpoint of the study, the observation of HHI rechallenge is noteworthy, especially considering that approximately 20% of the present cohort had prior vismodegib treatment. Increasingly common in Spain, rechallenging with HHIs is supported by studies showing its efficacy profile after treatment discontinuations due to tolerability issues or disease progression.11,24–30 Switching from vismodegib to sonidegib has improved tolerability, with reduced dysgeusia, alopecia, muscle spasms, weight loss, and fatigue.24 A retrospective study found that among laBCC patients relapsing after discontinuing vismodegib, 85% achieved an objective response upon rechallenge (37% CR, 48% PR).25–30 Further research is needed to optimize strategies for managing laBCC after HHI treatment.

An important strength of this interim analysis lies in its contribution to understanding the safety profile of sonidegib in elderly patients. The median age of the cohort was 81 years, notably higher than in previous trials such as the BOLT trial. Despite the advanced age and potential for increased frailty and comorbidities, the safety profile remained manageable, with most TEAEs being mild or moderate and a relatively low rate of serious drug-related events. These findings are consitent with tolerability data for sonidegib in older populations,31,32 reinforcing its real-world use in patients who often represent the typical clinical profile encountered in the treatment of laBCC.

Finally, the findings of this study are partly consistent with other real-world studies conducted in Spanish populations. For instance, the retrospective study by Moreno-Arrones et al. included 81 patients treated with sonidegib in routine clinical practice and reported a similar treatment discontinuation rate (20% vs 19.6% in our cohort).11 However, our study population was older on average (81 vs 73 years), which may account for certain differences in treatment duration or safety outcomes. Furthermore, our data are derived from a prospective, post-authorization observational design, thereby contributing robust evidence on the tolerability of sonidegib in a more elderly and clinically representative patient population.

While this interim analysis of the NISSO study supports previous findings and fills data gaps, it is essential to consider the limitations of observational studies, including the lack of a comparator arm and independent central review. Additionally, the relatively small sample size analyzed in this study (51 patients) limits the generalizability of the findings. Nonetheless, these results provide valuable real-world data on the long-term safety of sonidegib for patients with laBCC in the real-world clinical context of the Spain healthcare.

ConclusionsThe interim findings from the NISSO observational safety Spanish cohort suggest that sonidegib is well-tolerated across a diverse patient population in routine clinical settings. The safety profile observed is consistent with previously published data of the BOLT trial. As a result, our study supports the use of sonidegib as a systemic therapy for patients with laBCC within the Spanish healthcare system.

FundingClinical trial and medical writing funded by Sun Pharmaceuticals Industries Ltd.

Conflicts of interestAF has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Sun Pharma, and Takeda; consulting fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Galderma, Kyowa Kirin, Leo Pharma, Roche Farma, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB Biosciences GmbH; and has participated in clinical trials and research supported by AbbVie, Acelyrin Inc, Alcedis GmbH, Almirall, Amgen, Celgene, Galderma, Incyte Corporation, Janssen-Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Sun Pharma, and UCB Biosciences GmbH. ATA has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Sun Pharma. GMPP has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Merck and Sun Pharma and has served as a speaker for Almirall and Sun Pharma. JMG reports grants from Almirall and Leo Pharma, and personal fees from Almirall, BMS, Isdin, La Roche-Posay, Leo Pharma, Pierre Fabre, Roche, and Sun Pharma, outside the submitted work. MJFG has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Almirall and Sun Pharma. MMA has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Novartis and Sun Pharma. PBF has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Sun Pharma, provided advisory services for Sun Pharma, and attended conferences supported by Almirall, Galderma, Isdin, and Sun Pharma. PVA has received speaker honoraria from Isdin and Sun Pharma and received support from Almirall, Cantabria Labs, and UCB. RA is an employee of Sun Pharma. RFE (Dr Botella-Estrada) has served as a consultant, paid speaker, and/or participated in clinical trials sponsored by AbbVie, Almirall, Celgene, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Sun Pharma. RFM has received consulting fees from Kyowa, Recordati, and Sun Pharma, attended meetings supported by AbbVie, Almirall, Kyowa, and Sun Pharma, and served on an advisory board for Sun Pharma. SBA has participated in clinical trials sponsored by MSD, Regeneron, and Sun Pharma; received speaker honoraria from Cantabria Labs, MSD, and Sun Pharma; and provided advisory services for Regeneron and Sun Pharma. VRS has provided consultancy and advisory services for Almirall, Roche Farma, and Sun Pharma, and has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Ojer Pharma and Sun Pharma.

The authors wish to thank Jesús Loureiro and Ergon (Madrid, Spain) for their help with medical writing.