The Spanish National Cutaneous Melanoma Registry (Registro Nacional de Melanoma Cutáneo [RNMC]) was created in 1997 to record the characteristics of melanoma at diagnosis. In this article, we describe the characteristics of these tumors at diagnosis.

Patients and methodsThis was a cross-sectional observational study of prevalent and incident cases of melanoma for which initial biopsy results were available in the population-based RNMC.

ResultsThe RNMC contains information on 14,039 patients. We analyzed the characteristics of 13,628 melanomas diagnosed between 1997 and 2011. In total, 56.5% of the patients studied were women and 43.5% were men. The mean age of the group was 57 years (95% CI, 56.4-57 years) while median age was 58 years. The most common tumor site was the trunk (37.1%), followed by the lower limbs (27.3%). The most frequent clinical-pathologic subtype was superficial spreading melanoma (n=7481, 62.6%), followed by nodular melanoma (n=2014, 16.8%). Localized disease was observed in 86.2% of cases (n=10,382), regional metastasis in 9.9% (n=1188), and distant metastasis in 3.9% (n=479). Independently of age at diagnosis, men had thicker tumors, more ulceration, higher lactate dehydrogenase levels, and a higher rate of metastasis than women (P<.001).

ConclusionsBased on our findings, melanoma prevention campaigns should primarily target men over 50 years old because they tend to develop thicker tumors and therefore have a worse prognosis.

El registro nacional de melanoma cutáneo (RNMC) se creó en el año 1997 con el objetivo de conocer las características del melanoma en el momento del diagnóstico. Se muestran las características de los tumores en el momento de su diagnóstico inicial.

Pacientes y métodosRegistro observacional transversal, con base poblacional. Se incluyeron casos incidentes y prevalentes de melanoma con resultados de la primera biopsia disponibles.

ResultadosEl RNMC contiene información de 14.039 pacientes. Se analizaron las características del melanoma en los pacientes diagnosticados en el periodo 1997-2011, sumando un total de 13.628 melanomas. El 56,5% de los pacientes eran mujeres y el 43,5% hombres. La edad media fue de 57 años (IC 95%: 56,4 a 57), con mediana de 58 años. La localización más frecuente fue en el tronco (37,1%), seguido de la extremidad inferior (27,3%). El tipo clínico-patológico más observado fue el melanoma de extensión superficial en un 62,6% (n=7.481), seguido del melanoma nodular en un 16,8% de los casos (n=2.014). El 86,2% (n=10.382) tenían enfermedad localizada, el 9,9% metástasis regionales (n=1.188) y el 3,9% (n=479) a distancia. Se observó en los hombres, independientemente de la edad de diagnóstico, un mayor espesor del tumor y una mayor proporción de tumores ulcerados, con niveles de lactatodeshidrogenasa elevados y con enfermedad metastásica (p<0,0001).

ConclusionesCon los resultados observados las campañas preventivas deberían orientarse al colectivo masculino mayor de 50 años, en el que se observan tumores de mayor espesor, y por lo tanto de peor pronóstico.

According to data published by the Spanish national epidemiology institute (Carlos III Health Institute), the annual incidence of melanoma in Spain is close to the adjusted annual incidence for the European population of 6.14 per 100000 population in men and 7.26 per 100000 population in women.1 In the past 20 years, a substantial increase in the incidence of this tumor has been registered in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and the United States,2,3 but in Spain we lack the data that would allow us to analyze the true scale of the problem in this country. However, the findings of various regional studies indicate that the incidence in Spain may differ from that of other European countries.4–9 For example, up to 15 new cases per year per 100000 inhabitants have been reported in northern Europe, that is, double the incidence observed in Spain.1,10–12

The increase in incidence rates ranges from 3% to 7%, making melanoma one of the cancers with the fastest growing incidences in recent years. In Europe, approximately 60000 new cases are diagnosed every year.

The data on the characteristics of melanoma in Spain are derived essentially from cancer registries, which collect data on tumors diagnosed in different provinces or autonomous communities. These registries currently cover more than 25% of the Spanish population, and their geographic distribution throughout the country means that they provide valuable information on the variability of the incidence of the tumor in Spain. There are 14 fully operational, population-based general cancer registries in Spain: Albacete, Asturias, Canary Islands, Cantabria, Cuenca, Girona, Granada, Mallorca, Murcia, Navarre, Basque Country, La Rioja, Tarragona, and Zaragoza.4,13,14 However, the data on melanoma are incomplete given that these are general cancer registries. They do not collect information on risk factors, disease characteristics, or the treatments received by patients because their primary objective is epidemiologic surveillance, that is, to record incidence, prevalence, and overall disease-free survival.

The Spanish Cutaneous Melanoma Registry (Registro Nacional de Melanoma Cutáneo [RNMC]) was created in 1997 to record the incidence, clinicopathologic characteristics, and prognosis of melanoma at diagnosis in Spain. The data provided by this registry are useful for epidemiologic surveillance and can provide guidance to the preventive campaigns organized regularly by the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV). It is a simple and flexible registry that is well accepted by the participating clinicians. The number of cases reported annually has remained stable at approximately 900 from 1997 through 2011. The registry has been kept running largely thanks to the efforts of the various coordinators who have participated in the dissemination of the aims and findings of the RMNC over these 14 years. The impact of the findings has led to an extension of the project with the aim of gathering information on patient outcomes and studying the effectiveness of the treatments currently available. This second phase began in June 2012, after it was presented to the members of the AEDV at the national Dermatology Congress in Oviedo, Spain, in 2012.

The aim of this article is to analyze the characteristics of the tumors reported during the period the registry has been operational and the changes in the main prognostic factors.

Patients and MethodsStudy Design and EthicsThe RNMC was set up in 1997 as a cross-sectional observational registry. It comprises a database of personal patient information and is registered with the Spanish Data Protection Agency as a high-security private database with the identifier 2052370059.

Notifications can be made by mail, fax, or online forms. Cases reported to the RNMC in a calendar year later than that of the initial diagnosis are entered by year of diagnosis after checking for duplicate entries. The database is therefore retrospectively cumulative. Since there is a delay between the diagnosis of a case and notification of the RMNC, the number of cases registered for the current year is usually lower than for preceding years.

The data presented here correspond to diagnoses reported between 1997 and 2011. Prior to 1997, the information available was incomplete.

OrganizationThe RNMC is a national registry run by the AEDV Foundation. The organizational structure consists of a national coordinator, a scientific committee of 5 dermatologists responsible for coordinating the registry (each one in a given region), a scientific coordinator, and external consultants. The operating procedures are laid down in 6 documents: seasonal scheduling, a financial plan, a coordination plan, a standard operating procedures manual, a statistical analysis manual, and a document defining the procedures for reporting and dissemination. All these documents are based on the tenets of good registry practice published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the ethical guidelines for the creation and use of registries for biomedical research published by the Carlos III Health Institute.15,16

Inclusion and Exclusion CriteriaThe patients included on the registry had to have a first diagnosis (incident cases) or a previous diagnosis (prevalent cases) of melanoma. The result from the first diagnostic biopsy, which confirmed melanoma diagnosis, had to be available. In addition, the case history had to include a minimum basic dataset comprising the date of the first diagnosis of melanoma, date of birth, sex, date of assessment, province where the diagnosis was made, and disease status at diagnosis (localized disease, regional metastasis, or distant metastasis).

Assessment VariablesInitially, the registry record included the patient identifier, date of diagnosis, tumor-related epidemiologic data, site, histopathology, and tumor size. As the project progressed, other variables were added because they were considered necessary for complete assessment of the patients. No data are available on these additional variables for the cases registered prior to the date on which these changes came into effect. The variables introduced in 2005 were presence of ulceration in the tumor, lactate-dehydrogenase (LDH) level, and classification according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging System.

Statistical AnalysisGiven that the RNMC is a population-based registry, no formal sample size calculation was performed.

The analyses of tumor depth and extension only include data from patients with invasive melanoma and excludes cases in which the sex of the patient was unknown.

Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were calculated for qualitative variables. Comparisons between groups for such variables were performed using the Fisher exact test or the χ2 test, as appropriate.

Means with their corresponding 95% CIs and medians were calculated for quantitative variables. For such variables, group comparisons were performed using the t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Bonferroni or Games-Howell corrections to control for errors due to multiple comparisons. Multiple linear regression analyses were used to assess changes in the age of the patients at the time of diagnosis, tumor thickness (Breslow index [BI]) according to the year of diagnosis of the tumor, age, and sex of the patient. Statistical significance was set at .05. The statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS program, version 14.0 (SPSS Inc).

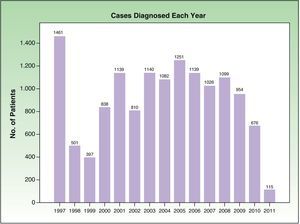

ResultsInclusion of patients in the RMNCThe RMNC contains information on 14039 patients. Data were analyzed from the 13628 patients diagnosed after January 1, 1997. In the present article, we present the results for invasive melanomas, of which there were a total of 10741 (78.8% of all melanomas). Figure 1 shows the cases diagnosed per year during the period analyzed.

In total, 342 dermatologists participated in the project, with a mean of 42 cases per specialist (95% CI, 29-53 cases). Thirty-three of these dermatologists accounted for 70% of the patients recorded in the RNMC (9863 patients).

The registry project covered patients attended in clinics in 266 public and private centers. The mean number of cases per center was 51 (95% CI, 34-67 cases). Twenty-four centers accounted for 70% of the patients included in the registry.

Cases were reported to the registry from all 17 autonomous communities. The autonomous communities that reported the largest number of cases to the registry were Catalonia, Madrid, and Valencia, with these communities accounting for 63% of the notifications. Table 1 shows the inclusion data for patients by autonomous community and the nationwide total during the analysis period. Cases from 49 provinces were included; Ceuta and Melilla were not represented.

Number of New Cases Diagnosed and Reported to the Spanish Cutaneous Melanoma Registry (RNMC) Between 1997 and 2011 by Autonomous Community and Sex.

| Autonomous Community | Sex | Total | ||||||

| Men | Women | Not Reported | ||||||

| Na | %b | Na | %b | Na | %b | Na | %b | |

| Andalusia | 384 | 6.6 | 597 | 7.9 | 26 | 12.3 | 1007 | 7.4 |

| Aragon | 38 | 0.7 | 62 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 100 | 0.7% |

| Canary Islands | 464 | 8.0 | 645 | 8.5 | 17 | 8.1 | 1126 | 8.3 |

| Cantabria | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.0 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 165 | 2.8 | 202 | 2.7 | 10 | 4.7 | 377 | 2.8 |

| Castile-León | 490 | 8.4 | 704 | 9.3 | 8 | 3.8 | 1202 | 8.8 |

| Catalonia | 1891 | 32.4 | 2341 | 30.9 | 108 | 51.2 | 4340 | 31.8 |

| Community of Madrid | 1079 | 18.5 | 1382 | 18.2 | 23 | 10.9 | 2484 | 18.2 |

| Community of Valencia | 910 | 15.6 | 1020 | 13.4 | 9 | 4.3 | 1939 | 14.2 |

| Extremadura | 22 | 0.4 | 17 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 39 | 0.3 |

| Galicia | 69 | 1.2 | 112 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 181 | 1.3 |

| Balearic Islands | 55 | 0.9 | 60 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 115 | 0.8 |

| La Rioja | 9 | 0.2 | 13 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 22 | 0.2 |

| Navarre | 14 | 0.2 | 11 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.9 | 27 | 0.2 |

| Basque Country | 10 | 0.2 | 15 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 25 | 0.2 |

| Asturias | 98 | 1.7 | 211 | 2.8 | 1 | 0.5 | 310 | 2.3 |

| Murcia | 135 | 2.3 | 189 | 2.5 | 7 | 3.3 | 331 | 2.4 |

| Total | 5833 | 100.0 | 7584 | 100.0 | 211 | 100.0 | 13 628 | 100.0 |

Of the patients included in the registry, 56.5% were women (n=7584) and 43.5% (n=5833) were men. The sex of the patient was not recorded in 211 cases (1.5%). Table 2 shows the data for patients with invasive melanoma.

Patient and Melanoma Characteristics on Diagnosis of Invasive Melanoma (1997-2011).

| Male | Female | Total | ||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | |

| Population | 4664 | 44.1 | 5917 | 55.9 | 10 581 | 100 |

| Age on diagnosis | ||||||

| <20a | 46 | 1 | 99 | 1.7 | 145 | 1.4 |

| 21-40a | 811 | 17.6 | 1319 | 22.6 | 2130 | 20.4 |

| 41-60 | 1638 | 35.5 | 2082 | 35.6 | 3720 | 35.6 |

| 61-80a | 1778 | 38.6 | 1860 | 31.8 | 3638 | 34.8 |

| >80 | 337 | 7.3 | 484 | 8.3 | 821 | 7.9 |

| Site | ||||||

| Heada | 790 | 20 | 777 | 15.2 | 1567 | 17.3 |

| Trunka | 2054 | 51.9 | 1506 | 29.4 | 3560 | 39.2 |

| Armsa | 468 | 11.8 | 848 | 16.6 | 1316 | 14.5 |

| Legsa | 632 | 15.9 | 1953 | 38.1 | 2585 | 28.4 |

| Mucosas | 16 | 0.4 | 36 | 0.7 | 52 | 0.6 |

| Anatomic type | ||||||

| LMM | 376 | 8.8 | 492 | 9 | 868 | 8.9 |

| SSMa | 2700 | 62.9 | 3653 | 66.9 | 6353 | 65.1 |

| ALM | 233 | 5.4 | 334 | 6.1 | 567 | 5.8 |

| NMa | 968 | 22.5 | 963 | 17.6 | 1.931 | 19.8 |

| Mucosas | 17 | 0.4 | 20 | 0.4 | 37 | 0.4 |

| Clark level | ||||||

| Clark I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clark IIa | 1171 | 26.7 | 1725 | 31.1 | 2896 | 29.1 |

| Clark III | 1662 | 37.8 | 2057 | 37.1 | 3719 | 37.4 |

| Clark IVa | 1282 | 29.2 | 1473 | 26.6 | 2755 | 27.2 |

| Clark Va | 278 | 6.3 | 291 | 5.2 | 569 | 5.7 |

| Breslow index | ||||||

| <1mma | 2127 | 45.6 | 3174 | 53.6 | 5301 | 50.1 |

| 1.01 to 2mm | 980 | 21 | 1275 | 21.5 | 2255 | 21.3 |

| 2.01 to 4mma | 876 | 18.8 | 884 | 14.9 | 1760 | 16.6 |

| >4mma | 681 | 14.6 | 584 | 9.9 | 1265 | 12 |

| Presence of ulceration in histopathology | ||||||

| No | 2534 | 76.3 | 3353 | 81.9 | 5887 | 79.4 |

| Yesa | 788 | 23.7 | 742 | 18.1 | 1530 | 20.6 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | ||||||

| Normal | 1190 | 96.1 | 1424 | 96.3 | 2614 | 96.2 |

| Elevateda | 48 | 3.9 | 55 | 3.7 | 103 | 3.8 |

| Disease stage on diagnosis | ||||||

| Localized diseasea | 3542 | 80.1 | 4833 | 86 | 8375 | 83.4 |

| Regional metastasisa | 618 | 14 | 570 | 10.1 | 1188 | 11.8 |

| Distant metastasisa | 263 | 5.9 | 216 | 3.9 | 479 | 4.8 |

| AJCC clinical staging | ||||||

| 0 | 797 | 43.5 | 1018 | 46.2 | 1815 | 46.1 |

| IAa | 429 | 23.4 | 596 | 27.1 | 1025 | 26.0 |

| IB | 186 | 10.1 | 243 | 11 | 429 | 10.9 |

| IIA | 106 | 5.8 | 101 | 4.6 | 207 | 5.3 |

| IIBa | 12 | 6.1 | 88 | 4 | 100 | 2.5 |

| IICa | 41 | 2.2 | 30 | 1.4 | 71 | 1.8 |

| IIIA | 64 | 3.5 | 64 | 2.9 | 128 | 3.3 |

| IIIBa | 40 | 2.2 | 26 | 1.2 | 66 | 1.7 |

| IIICa | 23 | 1.3 | 14 | 0.6 | 37 | 0.9 |

| IVa | 36 | 2 | 23 | 1 | 59 | 1.5 |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American joint committee on cancer; ALM, acral lentiginous melanoma; LMM, lentigo maligna melanoma; NM, nodular melanoma; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma.

The mean age for the whole group was 57 years (95% CI, 56.4-57 years), the median age was 58 years, and the range was from 3 to 100 years. A statistically significant difference between the sexes was observed in the age of the patients at the time of diagnosis, with men being diagnosed on average 2.2 years later (P<.0001). For women, the mean age was 55.8 years (95% CI, 55.4-56.2 years), the median age was 56 years, and the range was 3 to 100 years. For men, the mean age was 57.9 years (95% CI, 57.5-58.4 years), the median age was 60 years, and the range was 4 to 96 years.

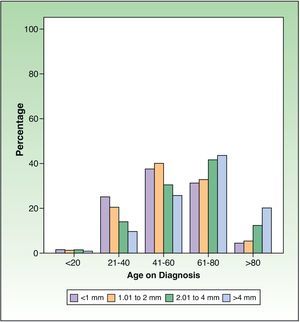

The distribution by ages was as follows: 1.3% (n=175) less than 20 years; 19.5% (n = 2585) between 21 and 40 years; 34.7% (n=4601) between 41 and 60 years; 36.3% (n=4811) between 61 and 80 years, and 8.2% (n=1086) over 80 years. The proportion of girls and women was significantly higher in the group aged under 20 years and the group aged between 21 and 40 years (P<.0001). In the group aged 61 to 80 years, the proportion of men significantly exceeded that of women (P<.0001). There were no significant differences in the proportions of men and women in the groups aged 41 to 60 years and those aged over 80 years. Table 2 shows the age distribution for the group of patients with invasive melanoma.

Characteristics of Primary Melanoma at DiagnosisSiteThe most frequent melanoma site was the trunk (n=4210; 37.1%), followed by the legs (n=3098; 27.3%), head (n=2362; 20.8%), arms (n=1602; 14.1%), and mucosas (n=80; 0.7%). Of the tumors on the trunk, 27.5% (n =1081) were located on the anterior aspect and 72.5% (n=2843) on the posterior aspect; the aspect was not recorded in 286 cases. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of invasive melanoma at the time of diagnosis according to sex of the patient.

There were differences between men and women for all melanoma sites (P<.0001), except for mucosal tumors. The head and trunk were the most frequent sites in men, whereas in women, the arms and legs were more frequently affected. Table 2 shows the data corresponding to the patients with invasive melanoma.

Clinicopathologic VariantsIn the group of patients as a whole, the most frequent clinicopathologic variant was superficial spreading melanoma (SSM) (n=7481; 62.6%), followed by nodular melanoma (NM) (n=2014; 16.8%), and lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM) (n=1705; 14.3% [1705 cases]). Acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) and mucosal melanoma accounted for 5.8% (n=698) and 0.5% (n=61), respectively. Significant differences between the sexes were observed in the clinicopathologic type of tumor, with a greater proportion of SSM in women (n=4351, 64.2% vs n=3130, 60.4% in men) and NM in men (n=1010, 19.5% vs n=1004, 14.8% in women) (P<.0001). Table 2 shows the data corresponding to the patients with invasive melanoma. NMs occur more frequently in men from 21 years of age onwards (15.1% vs 13.3%) but the difference only becomes significant from 41 years onwards, with a frequency of 21% in men and 16.9% in women (P=.021) in patients aged 41 to 60 years, 25% in men and 18.7% in women (P<.0001) in patients aged 61 to 80 years, and 36.6% in men and 27.2% in women (P=.055) in patients aged over 80 years. In those under 20 years, the proportion of NM was identical in both sexes (23%).

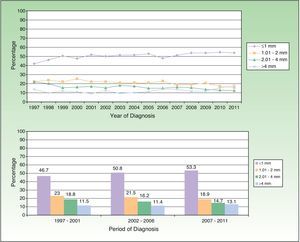

Depth of Invasion and Tumor ThicknessA total of 2044 patients (16%) had in situ melanoma. The proportions of patients with in situ melanoma by 5-year periods in the registry were as follows: 1997-2001, 16.1%; 2002-2006, 16.1%; and 2007-2011, 19.2%. The proportion was significantly greater in the most recent 5-year period with respect to the previous 2 periods (P<.0001).

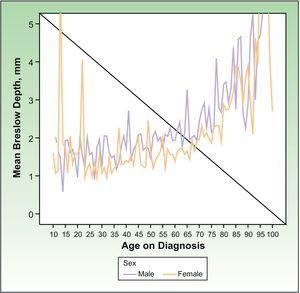

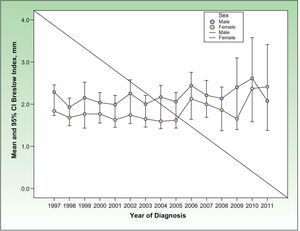

The following analyses were only performed for invasive melanomas. The mean BI was 1.97mm (95% CI, 1.91-2.03mm), with a median of 1mm. Statistically significant differences in BI were observed between men and women (P<.0001) with a mean BI 0.387mm (95% CI, 0.264-0.511mm) greater in men. The mean BI was 2.19 mm (95% CI, 2.09-2.28mm) in men and 1.80mm (95% CI, 1.72-1.88mm) in women.

In the multivariate analysis, BI was studied as a function of patient age and sex. Regardless of age, BI was greater in men than in women (P<.0001) by, on average, 0.346mm (95% CI, 0.223-0.469mm).

Regardless of sex, the BI increased significantly with increasing age (P<.0001), such that for each increase in age of a year, the BI on diagnosis increased 0.025mm (95% CI, 0.022-0.029mm), that is, 0.25mm every 10 years. Figure 2 depicts this trend.

Patients were classified according to T stage (tumor size) as per the AJCC guidelines for melanoma.17 Significant differences were observed in the proportion of patients of each sex who belonged to each BI category (Table 2), with a BI less than 1mm being more common in women than men (P<.0001) and a BI between 2.01 and 4mm or greater than 4mm being more common in men (P<.0001). Figure 3 shows the proportion of patients in each risk group by age.

The most frequently observed Clark level was Clark level III (n=3719; 37.4%). Statistically significant differences between men and women were observed in the proportion of patients in all categories (P<.0001), with Clark level II being more frequent in women and levels IV and V being more frequent in men (Table 2).

Ulceration in Anatomopathologic StudyTumor ulceration was present in 20.6% of the patients (n=1530) at the time of diagnosis (Table 2). A greater proportion of men than women had ulceration at the time of diagnosis (P<.0001). Since ulceration could be related to tumor depth at the time of diagnosis, an analysis was performed to assess whether these differences were independent of Breslow risk group. No statistically significant differences were observed between men and women in the presence of ulceration on diagnosis when this was analyzed according to tumor depth.

Tumor Extension in Invasive MelanomasWhen recorded, LDH was within the limits of normal on diagnosis in 96.1% of the patients (n=2614) while 3.8% (n=103) had high LDH values. In 7980 cases (74.3%), this value was not reported. No differences were observed between men and women.

StageThe stage was reported as in situ melanoma in 2007 cases (16.7%) and 69.5% (n=8375) had localized disease on diagnosis. Regional and distant metastases were reported in 9.9% (n=1188) and 3.9% (n=479), respectively; thus 1667 patients (13.8%) had metastatic disease on diagnosis.

As shown in Table 2, in situ and localized melanoma occurred significantly more frequently in women (P<.0001). Regional and distant metastases were more frequent among men (P<.0001).

Table 2 shows the information on AJCC classification. In 6655 cases (62%), this classification was not reported.

A greater proportion of men had tumors staged as iib, iic, iiib, iiic, and iv while in women, a greater proportion were staged as ia (P<.0001).

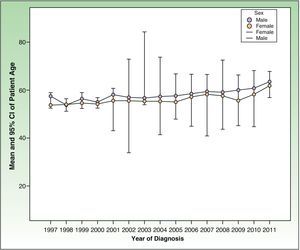

Differences in Tumor Characteristics by Year of DiagnosisPatient Age at the Time of DiagnosisA statistically significant increase (P<.0001) was seen in patient age on diagnosis according to the year in which the patient was diagnosed (Fig. 4). The age of the patients on diagnosis increased 0.333 years for each year that had passed since the start of the project (95% CI, 0.258-0.409 y).

This annual increase in the age on diagnosis was observed in both men (0.337 y; 95% CI, 0.226-0.448 y) and women (0.316 y; 95% CI, 0.213-0.418 y).

The age at diagnosis of women remained below that of men throughout the whole study period from 1997 to 2011 (P<.0001).

Tumor Thickness on DiagnosisThere were no statistically significant differences in tumor thickness over the study period from 1997 to 2011 (P=.701). There was a trend towards an increase in BI according to the year of diagnosis, with an increase of 0.019mm for each year of the study period.

When the data for men and women were analyzed separately, the trend towards an increase in tumor thickness according to year of diagnosis remained statistically nonsignificant (P=.127 in men and P=.06 in women).

In the multivariate linear regression analysis, change in tumor thickness with patient age, sex, and year of diagnosis was analyzed. No significant differences in tumor thickness were observed according to year of diagnosis (P=.171), though there was a (nonsignificant) trend towards increasing tumor thickness of 0.011mm per year of diagnosis (95% CI, 0.005-0.026mm). Figure 5 shows the change in the variable by year of diagnosis of the tumor.

Figure 6 shows the changes in the proportion of invasive melanomas by year of diagnosis according to their thickness (divided into 4 groups) and the comparison of the proportions of each group of thicknesses by 5-year periods. The increase in the proportion of diagnoses of melanomas under 1mm was significant between 2002 and 2006 and between 2007 and 2011 compared to the period between 1997 and 2001 (P<.001), as was the reduction in the melanomas with a thickness of 1.01 to 2mm in the period between 2007 and 2011 and the 2 preceding 5-year periods (P<.0001). The proportion of melanomas with a thickness of 2.01 to 4mm decreased significantly (P<.0001) in the period between 1997 and 2001 and the 2 subsequent periods. The change in the proportion of tumors with thicknesses greater than 4 mm between the 5-year periods was not significant.

DiscussionIt is important to highlight that 342 clinicians have participated in reporting cases to the RNMC since it became operational in 1997. There was little change in the notification rate, reflecting the efforts of all participants. Although the number of cases recorded in some autonomous communities was below that expected (Table 1), on a nationwide level, the rate of notification was high for a specific tumor registry. However, the ideal situation would be to make melanoma a disease of mandatory notification, as is the case in the United States since 2010 (http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/document/NNDSS_history_spreadsheet_2013_for_web_v1.pdf) and Australia (http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/phact/Documents/is6-disease-notification.pdf). A minimum dataset can be filled out quickly and would contribute to the generation of very important data on disease control (www.registromelanoma.org). The highest number of cases were notified in 1997 when the project first started because of the participation of pathologists, although their interest waned over time. It is therefore very important to involve all clinicians responsible for the care of patients with melanoma in the notification and follow-up of patients to achieve the important goals of the project.

The frequency of tumors was 13% higher in women than men during the study period (Table 1). The greater number of tumors observed in women is in line with other international and Spanish registries.1–9

The mean age on initial diagnosis of the tumor was 57 years, a figure similar to that reported in other Spanish studies.4,7,8 A statistically significant increase was seen in the age of the patient at diagnosis by year of diagnosis (P<.0001), in both men and women (Fig. 4). Some authors have reported a similar observation,18,19 but others have not reported any statistically significant differences.20 The progressive increase in age could be explained by the failure of prevention campaigns to reach older individuals, especially men, so that these patients first consult with advanced primary tumors. Such an observation has in fact been reported in studies of melanoma prevention.21

The most frequent site was the trunk, followed by the legs, in line with Spanish and international studies. The legs were more frequently affected in women and the trunk was more frequently affected in men (Table 2).7,8,22 The cause of these differences should be investigated. They could conceivably be due to differences in exposure to sunlight between men and women.

The clinicopathologic type most frequently reported was SSM, in both men and women, followed by NM. These findings are consistent with the data published in Spanish and international studies.7,8,22

Assessment of tumor thickness is very important given that this variable has been shown to affect prognosis.23–29 The results from the RNMC between 1997 and 2011 show a nonsignificant trend towards increasing melanoma thickness (BI) with year of diagnosis (Figure 5). The progressive increase observed can be considered an indication of how early the tumors are being diagnosed. Similar findings have been reported in other Spanish studies.18 Analysis of tumor size distribution by 5-year period shows that the proportion of cases with tumors having a thickness greater than 4mm has not increased over the 14-year study period (Fig. 6). However, the proportion of thin tumors has increased over time, as has the proportion of in situ melanomas. These findings coincide with those observed in other geographic areas.30,31

Women were found more often in the group with a BI less than 1mm than men (P<.0001). In men, tumors of greater thickness are more frequent, that is, those with worse prognosis (Table 2). The BI is greater in men than women (P<.0001), regardless of age (Fig. 2), indicating that the tumors are more aggressive on diagnosis in men. In addition, NMs were more frequent in men aged over 41 years. This clinicopathologic type of melanoma has been associated with higher mortality and a more aggressive clinical behavior than other types of melanoma given its faster rate of growth than other tumors.32,33

In addition to targeting the general population, prevention campaigns should focus particularly on men over 50 years, a population in whom thicker tumors are observed. This finding may possibly be explained by a longer delay in diagnosis given that a correlation was observed in men between older age and thicker tumors on diagnosis.

In conclusion, we would like to highlight the value of a specific population-based registry of patients with melanoma and the importance of keeping the registry running. The AEDV Foundation, convinced of this need, has decided to broaden the objectives of the project to enable prospective follow-up of patients and the study of outcomes according to treatments received and known prognostic factors. A webpage has been created (www.registromelanoma.org) to facilitate access to the registry data for the participating specialists, and participation in the project has been opened to all specialists who treat melanoma patients.

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed their hospital's protocol on the publication of data concerning patients and that all patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consent.The authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

FundingThe study was sponsored by the Foundation of the Spanish Academy for Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV), and received funding from Schering-Plough SA and Bristol Myers Squibb SA. E-C-BIO SL were responsible for designing the study, managing consent, quality control, and the statistical analysis under contract from the AEDV Foundation.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We thank the 342 clinicians who regularly provided data for their participation in the study. They are ordered by the number of cases included (see the complete list in the additional material).

Please cite this article as: Ríos L, Nagore E, López J, Redondo P, Martí R, Fernández-de-Misa R, et al. Registro nacional de melanoma cutáneo. Características del tumor en el momento del diagnóstico: 15 años de experiencia. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:789–799.