Teledermatology has facilitated specialist care during the crisis caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, eliminating unnecessary office visits and the possible exposure of patients or dermatologists. However, teledermatology brings forward certain ethical and medicolegal questions. A medical consultation in which the patient is not physically present is still a medical act, to which all the usual ethical and medicolegal considerations and consequences apply. The patient’s right to autonomy and privacy, confidentiality, and data protection must be guaranteed. The patient must agree to remote consultation by giving informed consent, for which a safeguard clause should be included. Well-defined practice guidelines and uniform legislation are required to preserve the highest level of safety for transferred data. Adequate training is also needed to prevent circumstances involving what might be termed “telemalpractice.”

La práctica de la teledermatología (TD) durante la pandemia de COVID-19ha facilitado la atención dermatológica especializada en una situación de crisis, evitando desplazamientos innecesarios, sin poner en riesgo la seguridad de pacientes y dermatólogos. Sin embargo, también ha puesto en evidencia distintos aspectos éticos y médico-legales que plantea esta práctica médica. La consulta médica no presencial constituye un acto médico, aplicándosele todas las consideraciones y consecuencias éticas y médico-legales de cualquier relación médico-paciente. Debe garantizarse el derecho a la autonomía del paciente, el secreto profesional, la protección de datos, la intimidad y la confidencialidad. El paciente debe aceptar la TD, mediante el consentimiento informado, considerando de interés establecer una cláusula de salvaguarda. Se precisan pautas de actuación bien definidas y una legislación uniforme para preservar una máxima seguridad de los datos transferidos así como una formación adecuada para prevenir posibles situaciones de lo que podría denominarse "telemalpraxis".

Our health care system has suffered a tremendous impact due to the enormous pressure on patient care resulting from the pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 and its infection. Dermatologists have had to attend patients admitted with COVID-19, with involvement of multiple organs and systems, including the skin, with the uncertainty inherent to the lack of knowledge regarding a novel disease.

COVID-19has made access to dermatologic care a real challenge. Following the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO) on social distancing and quarantine to prevent transmission, and Royal Decree 463/2020, which declared the state of alarm,1 face-to-face consultations have been limited almost exclusively to urgent or preferential cases that are carefully selected and cannot be delayed.

Online consultations or medical care provided by means of new technologies and communications systems is a genuine medical act, in which the health care professional must interpret the situation and decide on the appropriate response in each case. Telemedicine (TM) or e-health is a care system that has been proving its worth for years in hospital and primary-care settings. In the current exceptional circumstances, many hospitals and primary-care centers have been using teledermatology (TD) to treat their dermatologic patients. The ability to record, store, exchange and analyze data and images at a distance using different means of communication, such as audio, video, and image, has put virtual consultations at the center of dermatologic care. Virtual consultations have made it possible to maintain care of nonurgent diseases without exposing dermatologist or patient to the risk of infection.

TD, understood as the application of information and communication technology (ICT) to the care of skin diseases, has for many years enjoyed a favorable position in the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) in terms of its rational application, provided that certain basic criteria are met, to improve the quality of care in skin health problems.2

Several modes of TD exist, including direct consultation (patient-dermatologist), indirect consultation (patient-clinic-dermatologist at a distance) and specialist opinion (by dermatologists seeking opinions on dermatopathology, dermoscopy, etc.). TD can be performed in real time (synchronous) or by saving and re-sending the information and images (asynchronous). TD allows for personalized, accessible, convenient, and profitable patient care. Some countries have reported a 10-fold to 15-fold increase in teleconsultations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Virtual consultations have, by their very nature, major limitations compared to face-to-face visits. Including virtual consultations in routine dermatology practice may lead ot new situations and problems inherent to a medical act “at a distance “in both space and time.3 This study aims to identify and clarify the main challenges and medicolegal aspects that dermatologists must deal with in regard to TC when they make it part of their practice: 1, the legal liability of the dermatologist; and 2, privacy and security of patient data.

BackgroundTC is an emerging technology in the consolidation phase in Spain.4 For good reason, TD represents one of the most common uses of TM.2 Nevertheless, it should be remembered that, even today, the main activity carried out by dermatologists takes place mainly in a face-to-face setting in outpatient consultations (hospitals, primary-care centers and private clinics). In fact, TD is involved in 1% (0.3%-3.0%) of dermatologic diagnoses.5 It is considered to be a good solution for attending isolated communities, where factors such as geographic isolation or transport times and costs are major factors affecting acces to health care,6,7 and in certain social contexts, such as penitentiaries, care homes for the elderly, catastrophes, military conflicts,8 and health care at sea.

The use of TD had already been duly validated by the scientific community before the COVID-19 pandemic.9 However, the emergency health care scenario the world has been experiencing as a result of the pandemic has, among the many other changes undergone by health care, led to an exponential increase in the use of TD.10–13 It was already an accepted practice in medical care, but it has now become instated and generalize,14 with the intention of staying.15 It is fair to acknowledge that TM has made it possible to maintain access to and continuity of patient care and to provide support to the professionals on the front lines,16 by optimizing face-to-face services and minimizing transmission of infection by SARS-CoV-2,17 thus even contributing to reducing the risk of new outbreaks.18,19

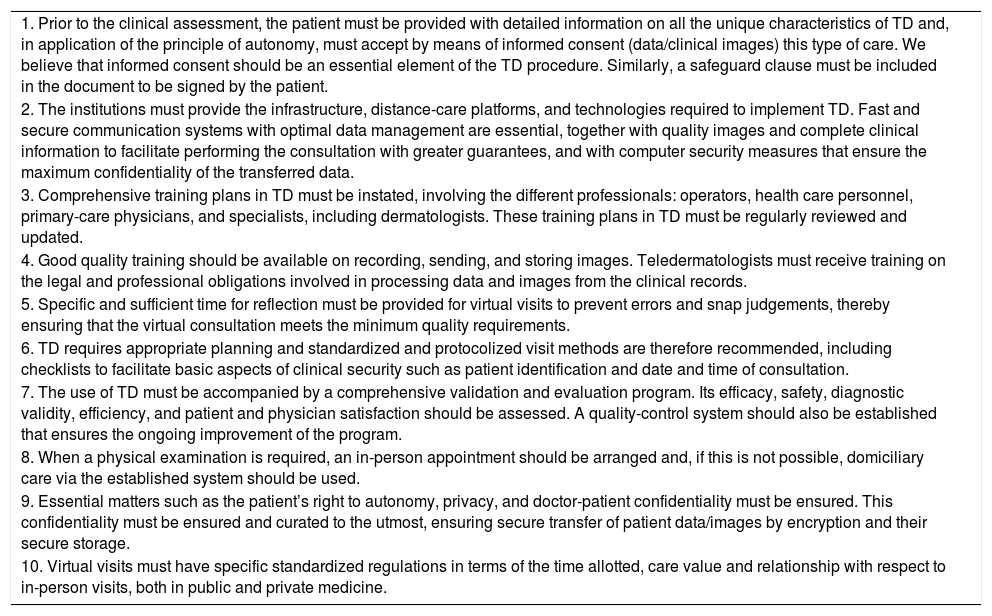

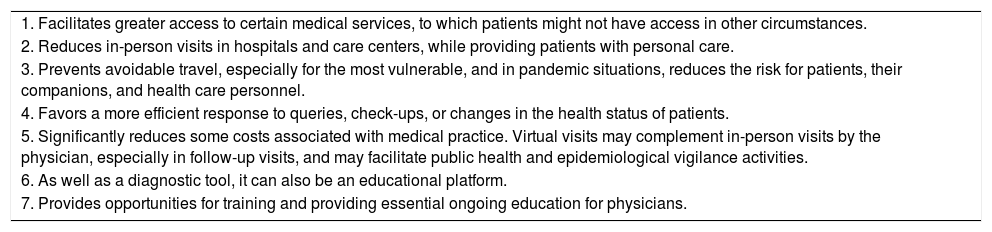

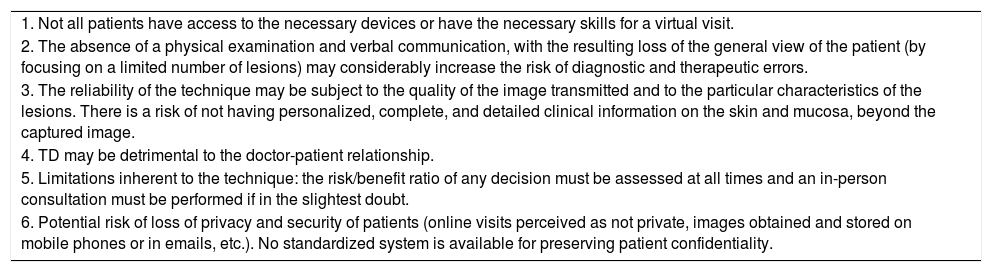

TD has a number of requirements, advantages, and disadvantages,20–23 some of which are shown in Tables 1–3. Despite the considerable proven value of TD, its mass use has been accompanied by matters of medicolegal debate,24–25 some of which are already on the table.

Requirements of teledermatology.

| 1. Prior to the clinical assessment, the patient must be provided with detailed information on all the unique characteristics of TD and, in application of the principle of autonomy, must accept by means of informed consent (data/clinical images) this type of care. We believe that informed consent should be an essential element of the TD procedure. Similarly, a safeguard clause must be included in the document to be signed by the patient. |

| 2. The institutions must provide the infrastructure, distance-care platforms, and technologies required to implement TD. Fast and secure communication systems with optimal data management are essential, together with quality images and complete clinical information to facilitate performing the consultation with greater guarantees, and with computer security measures that ensure the maximum confidentiality of the transferred data. |

| 3. Comprehensive training plans in TD must be instated, involving the different professionals: operators, health care personnel, primary-care physicians, and specialists, including dermatologists. These training plans in TD must be regularly reviewed and updated. |

| 4. Good quality training should be available on recording, sending, and storing images. Teledermatologists must receive training on the legal and professional obligations involved in processing data and images from the clinical records. |

| 5. Specific and sufficient time for reflection must be provided for virtual visits to prevent errors and snap judgements, thereby ensuring that the virtual consultation meets the minimum quality requirements. |

| 6. TD requires appropriate planning and standardized and protocolized visit methods are therefore recommended, including checklists to facilitate basic aspects of clinical security such as patient identification and date and time of consultation. |

| 7. The use of TD must be accompanied by a comprehensive validation and evaluation program. Its efficacy, safety, diagnostic validity, efficiency, and patient and physician satisfaction should be assessed. A quality-control system should also be established that ensures the ongoing improvement of the program. |

| 8. When a physical examination is required, an in-person appointment should be arranged and, if this is not possible, domiciliary care via the established system should be used. |

| 9. Essential matters such as the patient’s right to autonomy, privacy, and doctor-patient confidentiality must be ensured. This confidentiality must be ensured and curated to the utmost, ensuring secure transfer of patient data/images by encryption and their secure storage. |

| 10. Virtual visits must have specific standardized regulations in terms of the time allotted, care value and relationship with respect to in-person visits, both in public and private medicine. |

Advantages of teledermatology.

| 1. Facilitates greater access to certain medical services, to which patients might not have access in other circumstances. |

| 2. Reduces in-person visits in hospitals and care centers, while providing patients with personal care. |

| 3. Prevents avoidable travel, especially for the most vulnerable, and in pandemic situations, reduces the risk for patients, their companions, and health care personnel. |

| 4. Favors a more efficient response to queries, check-ups, or changes in the health status of patients. |

| 5. Significantly reduces some costs associated with medical practice. Virtual visits may complement in-person visits by the physician, especially in follow-up visits, and may facilitate public health and epidemiological vigilance activities. |

| 6. As well as a diagnostic tool, it can also be an educational platform. |

| 7. Provides opportunities for training and providing essential ongoing education for physicians. |

Disadvantages teledermatology.

| 1. Not all patients have access to the necessary devices or have the necessary skills for a virtual visit. |

| 2. The absence of a physical examination and verbal communication, with the resulting loss of the general view of the patient (by focusing on a limited number of lesions) may considerably increase the risk of diagnostic and therapeutic errors. |

| 3. The reliability of the technique may be subject to the quality of the image transmitted and to the particular characteristics of the lesions. There is a risk of not having personalized, complete, and detailed clinical information on the skin and mucosa, beyond the captured image. |

| 4. TD may be detrimental to the doctor-patient relationship. |

| 5. Limitations inherent to the technique: the risk/benefit ratio of any decision must be assessed at all times and an in-person consultation must be performed if in the slightest doubt. |

| 6. Potential risk of loss of privacy and security of patients (online visits perceived as not private, images obtained and stored on mobile phones or in emails, etc.). No standardized system is available for preserving patient confidentiality. |

If this were not enough, an exponential increase in the use of ICT is expected in the future in the field of dermatology, not just TD. In fact, today, where the mass use of instant messaging platforms on smartphones is ubiquitous, a recent study found that the preferred tool of dermatology patients for teleconsultations is the WhatsApp® application. In this regard, the lack of a clear legal framework or improper use of images may have negative repercussions for the dermatologist, which will make it necessary to regulate this type of consultation.26

TD is a useful educational tool for trainee specialists. It can contribute to improving the dermatology training of primary-care physicians and trainee specialists in both family medicine and dermatology.27 However, training in e-dermatology should not be seen as a substitute for in-person training of dermatologists. Both forms of training can coexist naturally, as a true reflection of current dermatologic practice, where in-person visits and TD visits will probably end up coexisting.

The spectacular technological progress, especially in ICT, and the social normalization of it uses and applications make it necessary to define and, if applicable, update the legal and ethical guidelines that affect them. We therefore have an historic opportunity to consolidate the rational use of TD, which must be seized to try, at the same time, to resolve the medicolegal questions it raises.

Teledermatology and LegislationPatients must receive specialist guidance prior to the virtual visit. The option of receiving distance care must be accepted and agreed with the patient, and the decisions that derive from it must also be agreed and not imposed by any of the parties involved.

It is absolutely essential to establish a policy that ensures data protection, not only by the different authorities but also by all the health care professionals involved, both in the transfer of data and images and in their receipt and storage.28

Different EU directives exist that can help to develop the activities of TM, but no specific legislation exists that regulates this practice and ensures respect for privacy and data protection without violating the standards of good clinical practice. According to EU legislation, TM is considered to be a health and information service. It is therefore subject to regulations relating to medical care and those relating to the information society. Thus, with regard to TD at present, the following documents must be taken into consideration: Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation [GDPR]), Directive 98/34/EC (Directive on Services of the Information Society), Directive 2000/31/EC (Directive on Electronic Commerce), Directive 2002/58/EC (Directive on Privacy and Electronic Communication), and Directive 2011/24/EC, relating to the application of patients’ 4 rights in cross-border health care. Nevertheless, several authors have highlighted and insisted on the need for a unified legislation for TD. Many point out the need for uniform guidelines to ensure the maximum security of data, similar to the General Data Protection Regulations in force in the European Union.

Teledermatology and Obligations of the PhysicianLike any medical act, TD is governed by the professional ethics set out in the Professional Code of Ethics29,30 on the doctor-patient relationship, the defense of patients’ rights and patient safety, and respect for health care professionals.

Dermatologists must be completely independent and free to choose or reject a visit by means of TD. When its use is accepted, the dermatologist assumes the professional responsibility of that medical act and everything that it involves, especially in terms of diagnosis, advice, therapeutic opinions and direct medical interventions, as well as the need for referral to a face-to-face consultation.

Physicians must be aware of the transcendent nature of the use of these communication systems and must assume the responsibilities inherent to their acts and must be aware of the direct and indirect harm that they may cause in ethical and legal terms.

It is essential to provide TD with legal security, as this practice throws up different legal and ethical questions in relation to medical acts performed via TM and in relation to the professional liability of the physician in the event of an incorrect virtual diagnosis.

Teledermatology and Responsibility of the Health Care Administration and the Health Care SystemThe different health care authorities are the main driver and, therefore, the main parties responsible for the consequences (advantages and disadvantages) that may arise from the introduction and implementation of these new models of virtual consultation.

They should therefore ensure that the organization of this virtual activity is implemented in an agreed and orderly manner in different the health care areas, introducing clear and concise criteria that involve recognition and control of the virtual activity.

Health care systems and medical directors must develop the necessary means for instating telematic medical systems that ensure patient access to health care and ensure privacy of communication.

They must establish the appropriate technical tools and regulations for the use of TD in the professional activity of physicians in the required conditions of legal security.

They must provide training for professionals and patients on the use of distance-care platforms. They must ensure the correct operation of these platforms by improving and facilitating the accessibility of communications networks.

Teledermatology, Clinical Security, and Medical Professional LiabilityOn the face of it, it seems evident that TD will lead to less diagnostic security and a greater number of erroneous diagnoses in specialist medical care. As an emerging technology, it therefore requires extreme caution in its use in diseases in which less diagnostic accuracy has been suggested,31 including inflammatory skin diseases and skin tumors.

The promotion of evidence-based medicine, the use of checklists and clear and visual standardized tools to facilitate medical activity and prevent errors, and the use of protocols and clinical-practice guidelines have proven to be effective tools for improving clinical security and for ensuring the quality of the medical act32 and, as a result, avoiding potential suits relating to medical professional liability Although dermatology is a specialty with a low risk of suits, both worldwide and in Spain,31 it would be advisable for AEDV to draft a proposal for clinical practice guidelines specific to TD, with the aim of regulating the process and providing dermatologists with clinical security.

The vast majority of medical professional liability (MPL) insurance policies do make specific mention of TM, although because it is a medical act, it is unequivocally covered by these policies. Malpractice in TM represents a new form of negligence but, for practical purposes, is not significantly different from malpractice in visits in which the patient is physically present. Some authors suggest expanding or implementing specific civil liability insurance policies for the practice of TM.3 Appropriate training of dermatologists is recommended in order to avoid and prevent these situations of “telemalpractice”.

Teledermatology, Right to Patient Autonomy, and ConfidentialityThe use of TD must ensure the right to the autonomy of the patient, doctor-patient confidentiality and data protection, and privacy. This requires an implicit will and consent, at least verbally, by the patient, responsible family member, or legal guardian, as applicable, which must be recorded in the patient’s medical records. The physician must have direct knowledge of the patient’s medical history or access to it at the time medical care is provided, and confidentiality and the patient’s privacy must be preserved, and doctor-patient confidentiality must be protected. The virtual medium used to perform the consultation and the recommendations and medical treatment prescribed must be indicated in writing in the patient’s medical records.

The practice of TD requires a procedure for informing on the purposes and uses of the images taken and transmitted. Any TD application must meet the confidentiality and privacy requirements set out in the law on the protection of personal data.2 Furthermore, and specifically in TD, special attention must be paid to the encryption of photographs when they are included in the clinical records or when they are updated, to make access by unauthorized users impossible.33 The necessary computer processing that makes such encryption possible is usually the responsibility of the care centers, whether private or public. Moreover, it must be remembered that in the case of private consultation, it is the physician who shall ensure the appropriate encryption of these data. The information must be stored in servers protected by computer firewalls.34 Whenever possible, the consultation should be recorded and stored in the clinical records as a clinical security measure for the patient and a legal security measure for the professional.

Teledermatology, Informed Consent, and Safeguard ClauseThe limitations of the use of TD should be specified in a safeguard clause included in the reports issued,2 especially in relation to asynchronous TD, where there is greater exposure of the dermatology specialist deriving from the accuracy of the information sent by the family physician from the patient history taken, and from the characteristics and greater or lesser quality of the means used and, therefore the audiovisual material sent.

If dermatologists simply accept these circumstances, provided the requisites of professional liability are met, the obligation of the physician to compensate (from their compulsory civil liability insurance policy) will arise. Dermatology specialists must, therefore, adapt the clinical documentation to this situation and these patient-care limitations. The fundamental measure in this regard would be to inform the patient in writing, by means of an informed consent document or an information leaflet signed by the patient, explaining these limitations and circumstances, while including a safeguard clause in the medical report issued describing the limitations and fallibility of the system used. An approximate formula is that used by ultrasound specialists in the reports issued during pregnancy controls. An example of a safeguard clause might be the following: “Telemedicine is a procedure for performing medicine that has the advantage of preventing the patient from having to travel in person but that obliges the physician to base his or her clinical judgement on image-capturing methods that, while efficacious and advanced, have limitations that may affect the diagnosis.”

Thus, as well as strictly complying with the protocol of the Organic Law on protection of personal data,35 we propose further specifying, in the general advice on compliance with the law on patient autonomy,36 the specific need to include on the information sheet the potential limitations and vicissitudes of the system, signed and accepted by the patient, and the safeguard clause in the medical report issued by the dermatologist, indicating the fallibility of the procedure. We would thus achieve, as described, good legal protection for the dermatologist against a potential liability suit.

Consent by the patient requires a thorough explanation of the unique characteristics of TM: it should include a clear and understandable demonstration of how it works, the advantages and disadvantages, and an explanation of potential privacy problems.

In conclusion, the practice of TD during the COVID-19 pandemic has facilitated access to specialist care and has made it possible to minimize unnecessary travel by patients, increase availability of services, and ensure the safety of patients and health care personnel. However, in order to protect both patients and professionals performing TD, the ethical and legal connotations that may arise from a virtual visit must be considered.

Medicolegal ConclusionsPrior to using TD, dermatologists require training that allows for the normal performance of these visits.

Before any visit by means of TD, technical image quality and appropriate information must be ensured that facilitate the correct technical performance of the visit, together with the computer security measures that ensure the confidentiality of the data transferred.

The use of TD is only justified by the best interests of the patient. As a result, the patient, in application of the principle of autonomy, must accept, by means of informed consent, this type of care act and the utility of establishing a safeguard clause must be considered.

A telemedicine (TM) consultation is a medical act. As a result, it is governed by all the ethical and medicolegal considerations and consequences that apply to any doctor-patient relationship.

TD requires appropriate planning and standardized and protocolized visit methods are therefore recommended, including checklists to facilitate basic aspects of clinical security such as patient identification and date and time of consultation.

The use of TD must meet the criteria of the normal practice of patient care (quality care, i.e., care administered with competence, due diligence and skill, efficacy, and efficiency).

The use of TD must ensure the right to autonomy of the patient, doctor-patient confidentiality and data protection, and privacy.

The use of TD requires that any circumstances relating to the medical act must be indicated in the clinical records (circumstances of the medical act, indicating whether it is a follow-up visit or an initial visit, or whether TD is synchronous or asynchronous, the problem in question, any missing data, indication of the intervention of other physicians, etc.).

If, after a visit, doubt remains regarding the diagnosis, or if the dermatologist deems it necessary for any other reason, the patient must be referred, in accordance with clinical-security criteria, by recommending a face-to-face medical visit.

Dermatologists must be completely independent and free to choose or reject a visit by means of TD. When its use is accepted, the dermatologist assumes the professional responsibility of that medical act and everything that it involved, especially in terms of diagnosis, advice, therapeutic opinions and direct medical interventions, as well as the need for referral to a face-to-face consultation.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Arimany-Manso J, Pujol RM, García-Patos V, Saigí U, Martin-Fumadó C. Aspectos médico-legales de la teledermatología. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:815–821.