Simultaneous skin infection by Pseudomonas and fungi is underdiagnosed. In the context of a complex case of this pathology, we reflect on the interaction between these 2 infectious agents, the mutual influences they exert, and how this circumstance can affect the clinical course and microbiological diagnosis.

We present the case of a 55-year-old man who consulted for cellulitis of the right lower limb with marked systemic repercussions, requiring hospital admission. Physical examination revealed intense erythema of both feet, with desquamation and exudation, particularly in the lateral interdigital spaces, compatible with tinea pedis (Fig. 1), and subungual hyperkeratosis of the nail of the great toes of both feet. Wood light did not elicit fluorescence, allowing us to exclude erythrasma.1

Routine laboratory tests and a basic study of immunity were normal. Samples taken for microbiology repeatedly grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacilli that varied in the different cultures performed (Proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli, and Morganella morganii). Direct examination of both nails with potassium hydroxide (KOH) showed distorted hyphae, but dermatophytes were not isolated in any of the specific cultures for fungi of the sole of the foot and affected nails. Based on the antibiogram, the patient received treatment with ciprofloxacin for 10 days, leading to an improvement and hospital discharge. During follow-up, the clinical suspicion of interdigital tinea pedis increased, though dermatophytes were not isolated in any of the 3 cultures performed, which always included samples from the sole of the foot and the affected nails. In a fourth culture, performed after complete disappearance of P.aeruginosa, the sample from the fourth interdigital space showed growth of Trichopyton rubrum and abundant yeasts (Candida albicans and Candida guilliermondii) were also isolated. The patient was treated with terbinafine, 250mg/d, for 28 days, leading to clinical and microbiological cure.

Tinea pedis, particularly the interdigital form, is the most common fungal infection.2 The warm, moist, and protected anatomic environment predisposes to the proliferation of fungi and gram-negative bacteria. Overgrowth of the normal flora of these spaces provokes maceration, peeling, and the appearance of fissures.

Intertrigo of the foot is usually caused by dermatophytes and yeasts and less commonly by bacteria. Polymicrobial infections are of particular importance, especially when P.aeruginosa is involved, as management can be complex, due both to the aggressiveness of the infection, which can produce potentially severe conditions such as cellulitis, and to therapeutic difficulties, because of a high frequency of antimicrobial resistence.3

A major problem with these polymicrobial infections arises from interactions between the different species involved: the presence of fungi in the lesions appears to favor colonization by P.aeruginosa,4,5 and bacterial overgrowth associated with interdigital infections of the foot can have a fungistatic or fungicidal effect. It has been shown that P.aeruginosa is able to inhibit both yeasts (C. albicans)6,7 and filamentous fungi (Aspergillus fumigatus, Fusarium species) in vitro.2,7,8 Furthermore, this inhibition can occur with various species of Pseudomonas, such as P.aeruginosa or P.clororaphis, but not with other bacteria, and the effect occurs specifically with the dermatophytes most frequently isolated in tinea pedis, such as Trichophyton.2,5,6,9

Returning to our patient, we created a simple in vitro model of the interaction between P.aeruginosa and T.rubrum. We observed that the dermatophyte did not grow after inoculation into a culture of P.aeruginosa (Fig. 2), a finding previously reported by other authors.2

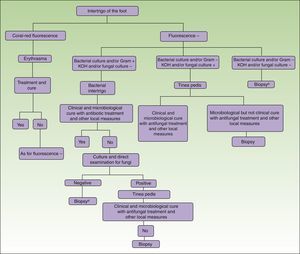

In conclusion, in patients with interdigital tinea pedis that is clinically extensive, intractable, or that recurs after treatment, we must consider possible reasons for diagnostic failure. These may be clinical, when the presence of bacteria is not considered in the diagnosis of tinea pedis, leading to inefficacy of an exclusively antifungal treatment, ormicrobiological, when the presence of bacteria is not sought or when overgrowth of P.aeruginosa is not contemplated as a possible cause of falsely negative dermatophyte culture. The application of a diagnostic protocol that includes systematic use of Wood light for the diagnosis of erythrasma (not forgetting possible mixed fungal infection)1 and taking samples to search both for fungi (particulary dermatophytes, but also yeasts) and for bacteria (especially gram-negative bacteria, including Pseudomonas), could help to define the microbiological etiology of the intertrigo and contribute to a reduction in diagnostic failure that will inevitably lead to inadequate treatment (Fig. 3). Finally, it must not be forgotten that, if all these investigations are negative or inconclusive, a biopsy will help to diagnose noninfectious diseases, such as inverse psoriasis or Bowen Disease.10

Diagnostic algorithm for intertrigo of the foot.

Other local measures include the application of topical antiseptics, the use of nonocclusive footwear and adequate drying of the affected area after showering or bathing. In addition, antifungal powders should be applied to the footwear to eliminate fungal spores that could provoke reinfection. When taking samples for culture of fungi or bacteria, no topical antifungal or antibiotic agents should have been used for at least 15days before sampling; in the case of systemic treatments, this period may need to be extended, as some agents remain in the stratum corneum for longer. KOH indicates direct examination with potassium hydroxide.

a When there is a high clinical suspicion of tinea pedis, empirical treatment with antifungal agents can be started before biopsy, even if direct examination and culture are negative, considering the possibility of a false negative.

We would like to thank Dr. Luis Charlez of the Dermatology Department of Hospital Royo Villanova in Saragossa, for his contribution to the diagnosis, treatment, and management of this case.

Please cite this article as: Aspiroz C, Toyas C, Robres P, Gilaberte Y. Interacción de Pseudomonas aeruginosa y hongos dermatofitos: repercusión en el curso clínico y en el diagnóstico microbiológico de la tinea pedis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:80–82.