The basic principle of a lobed or finger-like transposition flap is that, after covering the defect with the transposed tissue, the donor site is closed primarily. With large defects, a second lobe may be added to the flap if primary closure of the area left by the first lobe is not possible. The flap can often be made to adapt to the defect, but this maneuver, in combination with primary closure of the adjacent tissue, can sometimes produce excessive tension and compromise the blood supply.

Material and methodsWe present a series of 4 patients with epithelial tumors of the lateral wall of the nose. The defects left by surgical excision were covered by finger-like transposition flaps. Subcutaneous sutures called guitar-string sutures were used to reduce the size of the defect and facilitate tension-free closure.

ConclusionsWe propose use of the guitar-string subcutaneous suture in those cases in which the defect is larger than the area that can be covered by the flap. This will make it easier to adapt the flap to the defect and will reduce the risk of excessive tension causing necrosis of the transposed tissue.

El principio básico de un colgajo lobulado o digitiforme de trasposición es que una vez que el tejido desplazado cubra el defecto, la zona dadora cierre directamente. Cuando los defectos son grandes puede ser necesaria la realización de un segundo lóbulo, debido a que el área que deja el primer lóbulo con su movimiento no cumple el criterio anterior. Con frecuencia se puede forzar el colgajo y adaptarlo al nuevo lecho, aunque a veces esta maniobra, sumada al cierre directo del tejido adyacente, puede traccionar en exceso y comprometer la vascularización.

Material y métodosSe presenta una serie de 4 pacientes con tumores epiteliales en el lateral nasal. Tras la extirpación quirúrgica, los defectos resultantes se cubrieron mediante colgajos digitiformes de trasposición. En el diseño del cierre de los defectos se utilizaron unos puntos de sutura subcutáneos denominados en «cuerda de guitarra» para disminuir el tamaño del área cruenta y facilitar el ensamblaje del colgajo sin tensión.

ConclusionesProponemos la realización de la sutura subcutánea en «cuerda de guitarra» para aquellos casos en los que el defecto cutáneo es mayor que la cobertura que aporta el colgajo local, con el objetivo de facilitar su ensamblaje y disminuir el riesgo de necrosis del tejido desplazado por una excesiva tensión.

The finger-like or lobed transposition flap is a good therapeutic option for the reconstruction of defects of the lateral nasal wall in those cases which direct closure is not possible because of the lack of skin mobility or the risk of asymmetry due to traction. This flap is based on the design of a lobe of skin adjacent to the primary surgical defect and its transposition into the defect.1,2

During design of the flap, it is essential to take into account that the size of the flap must cover the defect and, at the same time, it must be possible to close the donor region directly.3 With large defects in which there is slight discrepancy between the size of the primary defect and that of the flap, the lobe can be adapted to the surgical site. However, this maneuver risks viability of the displaced tissue, as the resulting tension can affect its blood supply, leading to tissue necrosis. To avoid this complication, a second lobe can be created, transforming the initial design into a bilobed flap that distributes the tension over a larger surface area. However, placement of an approximation suture can be used to reduce the surface area of the defect so that the flap will cover it without modification of its design and without increasing the risk of tissue ischemia.

Materials and MethodsWe present a series of 4 patients (3 men and 1 woman) aged between 63 and 86 years (mean age, 75 years), with epithelial tumors of the lateral nasal wall (3basal cell carcinomas and 1 squamous cell carcinoma) treated surgically between March 2014 and March 2016. After complete excision of the lesions, the mean size of the resulting defects was 374mm2 (range, 100-540mm2). All reconstructions were performed using lobar transposition flaps of skin from the area of union of the lateral nasal wall with the ipsilateral cheek. Given the size of the defects, deep subcutaneous guitar-string approximation sutures were used to reduce the surface area to be covered, making it possible to suture the flap lobe in place without tension.

The guitar-string sutures enabled the surface area of the defects to be reduced by 15% to 45%. The clinical course was favorable in all 4 cases, with satisfactory healing and a good cosmetic result (Figs. 1–4).

A, Basal cell carcinoma on the lateral wall of the nose. Design of the excision and of the reconstruction using a lobar transposition flap from the adjacent skin. B, Flap dissected in the subcutaneous plane, transposed to cover the defect. There is a noticeable difference between the size of the flap and the surface area of the wound. C, Series of drawings to illustrate the use of 2 guitar-string sutures to reduce the size of the defect and allow tension-free fixation of the flap. D, Result immediately after suturing with 6/0 silk. E, Appearance at 24hours. F and G, Final outcome 2 months after surgery.

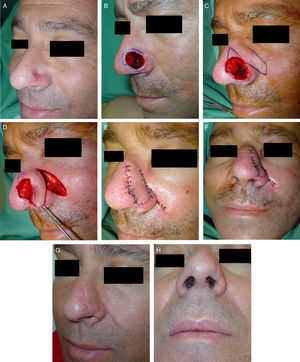

A, Patient referred to the dermatology department for Mohs micrographic surgery for a previously excised basal cell carcinoma on the lateral wall of the nose, with infiltration of the deep and lateral borders. Reconstruction with a transposition flap from the adjacent skin. B, Final defect and design of the transposition flap on the skin of the cheek overlying the superior part of the nasolabial sulcus. B, Flap dissected in the subcutaneous plane, transposed to cover the defect. Design of a small Burow triangle with the vertex directed towards the nasolabial fold. There is a noticeable difference between the size of the flap and the surface area of the wound. D and E, Maneuver to approximate the tissues with a guitar-string suture that reduces the size of the defect. F, Finally a second suture is placed a little lower to facilitate tension-free insertion of the displaced tissue into the new site. G, Result immediately after suturing with 6/0 silk. H, Appearance at 24hours.

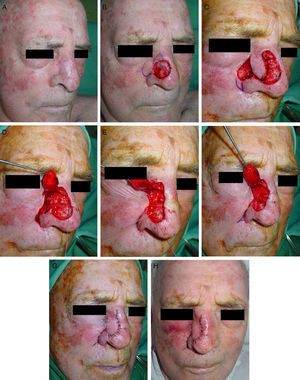

A, Male patient with carcinoma on the lateral wall of the nose that had recurred after previous surgery and radiotherapy, referred to perform 3-dimensional histologic study. B, Initial defect, with marking of the affected margins after histologic study of all the excision margins. C, Design of a lobar transposition flap on the skin superior to the defect, extending towards the nasolabial sulcus. D, Definitive defect after the final stage at the inferior part of the defect, close to the free border of the ala, and flap dissected along a deep plane. Transposition and rotation movement of the flap with the aid of a hook. E and F, Final outcome after transposition of the flap and suturing of the skin with 6/0 silk. Previously, the area of the wound had been reduced using a guitar-string suture. G and H, Final outcome 6 months after surgery.

A, Basal cell carcinoma on the lateral wall of the nose. B, Final defect and design of the method of reconstruction using a lobar transposition flap of skin from the nasofacial angle. B, Flap dissected in the subcutaneous plane, transposed to cover the defect. D, The diagrams illustrate approximation of the borders of the defect using 2 guitar-string sutures, the reduction in the surface area of the wound, and the final position of the lobar flap. E, Result immediately after suturing with 6/0 silk. E, Appearance at 24hours.

The procedure consists first of identifying the most widely separated borders of the defect. After manually checking the range of skin mobility, one or more deep subcutaneous sutures are placed (preferably between the deep dermis and the hypodermis), crossing the defect across its longest axis. The needle is inserted in the deep region of one of the borders of the wound and exits more superficially. It is then inserted symmetrically in the dermis of the opposite border, to exit deeply. Finally, a traction maneuver is performed to approximate the borders, without apposition, and the suture is tied at one of the borders. The previously extensive surgical defect is thus reduced and adapted to the lobe designed with a smaller size. The tension in the borders is homogeneously distributed across the areas with greatest blood supply; this will increase flap survival.

An absorbable suture material is used, choosing 3/0 or 4/0 depending on the tension to be applied in the tissue; we use braided polyglactin 910 (Novosyn, Braun, Spain). This type of suture maintains its tensile strength for 4 weeks after the operation, giving the wound sufficient time to form the necessary fibrous tissue to withstand the tension intrinsically after reabsorption of the suture. The use of this suture material also reduces the risk of postoperative complications, such as rejection and extrusion of the suture material or the persistent presence of a palpable knot beneath the skin.

DiscussionThe key to the correct use of the lobar flap for the reconstruction of defects of the external nose is that the lobe design must be of a sufficient size to cover the primary surgical defect, whilst allowing closure of the secondary defect by direct approximation. The orientation of the lobar flap is determined by the site of the defect, preferably on the lateral wall of the nose, where the skin is more lax and mobile, or at the union between the lateral wall of the nose and the cheek, in order to hide the resulting scar in the nasolabial or nasofacial sulcus.3

Sometimes, seeking a balance that will allow direct closure of the donor site, a narrow lobar flap is designed that does not completely cover the defect, and the impression that it will not wholly cover the defect can become accentuated as the flap is incised and lifted. In these cases, when the proportions are seen not to coincide, the lobar flap can be stretched by putting radial traction on its borders to adapt it to the surgical defect. This can lead to peripheral necrosis of the mobilized tissue, which will increase the risk of local infection and may require further operations to be performed to refresh the borders, or even the creation of new flaps or grafts.

An alternative in this situation is to reduce the size of the defect. To do this, we use approximation sutures between the movable borders of the defect. These sutures, called guitar-string sutures because of the similarity with the tension in the strings of that musical instrument, are subcutaneous sutures that approximate the most distant borders of the defect without bringing them fully together, reducing the surface area of the defect and adapting it to the size of the flap.4,5

A factor that must be taken into account is the mobility of the external nose when performing the approximation maneuver, as the fibrocartilaginous part of the nose is easily displaced by minor traction forces. When the surgical defect is on the lateral nasal wall, attempts to approximate the borders of the defect can give rise to ecnasion or displacement of the external nose in the same direction, producing undesirable asymmetry that distorts facial harmony.

There are other ways to reduce the size of a defect to facilitate its closure (Table 1). Plicature with forced approximation, proposed by Vilalta, is a surgical technique that uses a nonabsorbable suture to approximate the borders of a wound and thus promote and direct keratinocyte migration towards the cavity of the defect in order to accelerate granulation and epithelialization by second intention. Although cosmetic results are satisfactory with this technique, healing by second intention is slow and requires specific local wound care to create an appropriate environment and prevent local infection.6 Purse-string sutures distribute tension uniformly around the wound, contribute to hemostasis of the free tissue borders, and significantly reduce the size of the defect. However, the use of this surgical technique is restricted to round defects, uses nonabsorbable sutures that must be removed after 15 to 60 days, and its combination with plasties has not been described in the literature.7,8 Finally, indicated particularly for defects situated on the face, suspension sutures facilitate tension-free closure as well as preventing undesirable distortion of the facial folds by anchoring mobile tissues to fixed structures.9 The guitar-string suture can be seen as conceptually similar to a suspension suture. However, the basic objective of a suspension suture is union of the displaced skin to a fixed deeper point, typically periosteum, which acts as an anchor and helps to prevent undesirable facial asymmetry caused by the displacement of structures such as the eyelids, nose, or lips. The guitar-string suture, on the other hand, approximates equally 2 areas of mobile skin, easily identified as the most widely separated borders of the defect. Thus, whilst the objective of a suspension suture is to anchor the skin to avoid alterations of facial symmetry, the aim of the guitar-string suture is to reduce of the size of the defect.

Techniques to Facilitate the Closure of Large Defects.

| Technique | Indication | Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forced plicature | Large defects in which direct closure is not possible | Nonabsorbable suture that favors second-intention healing | Simple technique with a satisfactory cosmetic result | Long time to wound closure, requiring local wound care to prevent infection and promote healing |

| Purse-string suture | Round defects | Nonabsorbable suture; can be combined with grafts or direct closure of the ends of the wound | Simple, without the need to perform plasties | Limited to round defects |

| Suspension suture | Defects in facial areas close to mobile structures (lips, nose, etc.) | Absorbable suture that unites a mobile tissue with a fixed structure | Preservation of facial symmetry despite mobilization of the facial skin | Need for deep anchoring of the suture (periosteum) |

| Guitar-string suture | Reduction of the size of a defect to allow coverage by a flap or graft | Deep absorbable suture that approximates the borders of a defect without uniting them | Facilitates tension-free closure and reduces the risk of flap necrosis | Risk of asymmetry due to an excessive traction on facial tissues (ecnasion, eclabium) |

A possible disadvantage of the guitar-string suture is that it could theoretically act as a focus of infection, as it is a foreign body introduced into the skin. However, the risk is no greater than that of any other subcutaneous suture, and we have observed no increase in the risk of postoperative infection in our patients. It should also be noted that, as the borders of the defect are not undermined and as the suture is placed deep in the wound, the approximation does not create a dead space that could favor a tenting effect.

In summary, the guitar-string suture is a simple and rapid technique to reduce the size of large defects to adapt them to a flap that is of smaller size. Although this study describes its use to reconstruct defects in the lateral wall of the nose using lobed transposition flaps, the technique can be extrapolated to defects at other sites on the face, scalp, trunk, or limbs.

ConclusionsWe use the term guitar-string suture for those deep subcutaneous sutures whose aim is to approximate the borders of a defect to reduce its size and facilitate closure. Applied to the lobar transposition flap, this technique enables the final surface area of the wound to be reduced, allowing a smaller lobar flap to cover the defect without tension, without affecting its blood supply, and without the need to design a second lobe.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed their hospital's regulations regarding the publication of patient information.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Querol-Cisneros E, Redondo P. Suturas en «cuerda de guitarra» para facilitar el cierre del colgajo digitiforme en la reconstrucción nasal. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:657–664.