Gianotti-Crosti Syndrome (GCS) is a reactive, self-limited condition characterized by a symmetrical papular eruption, that occurs primarily in infants and is most commonly associated with viral infections.1,2 Here we report a unique case of an adult patient who developed a skin eruption shortly after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2, with clinical and histopathologic findings supporting the diagnosis of GCS.

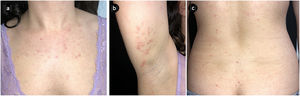

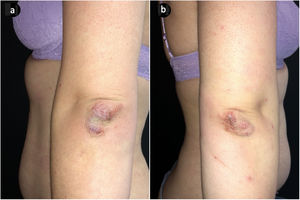

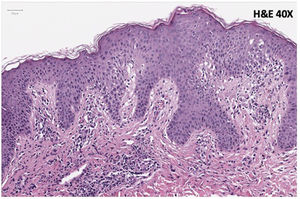

A 35-year-old woman was referred to our Dermatology clinic for a sudden pruritic papular rash. She reported that the skin lesions first appeared over her buttocks, soon spreading to the upper limbs, palms and trunk. Lesions were moderately itchy. Dermatological examination showed a symmetric eruption with erythematous papules, some of which crusted, 2–4mm in size, mainly affecting the upper limbs, palms and trunk and scarcely the buttocks (Fig. 1a–c). In the extensor surface of the elbows, some confluent papulovesicles were observed (Fig. 2a and b). Fever and lymphadenopathy were absent. The patient's medical history was only remarkable for allergic rhinitis. No history of recent infections or use of oral or topical medication was identified. Ten days prior to the beginning of the eruption, she had received the first dose of SARS-CoV-2 immunization Comirnaty®, a messenger RNA-based vaccine. Histopathological findings, although non-specific, were consistent with those described in GCS (Fig. 3). Symptomatic treatment with antihistamines was prescribed. Complete spontaneous regression of the skin lesions occurred after 12 days, with no scars or altered pigmentation. The second dose of SARS-CoV-2 immunization was administered 21 days after the first one, with no adverse effects reported.

Firstly described by Gianotti and Crosti in the 1950s, GCS is characterized by the acute onset of a symmetrical and monomorphic eruption, with millimetric skin-colored to pink-red flat-topped papules, mainly distributed on the face, buttocks and extensor surfaces of the extremities.1–3 Palms and soles may also be affected. The trunk is usually spared, although its involvement does not exclude the diagnosis. The lesions can become confluent, mostly over pressure points like knees and elbows and occasionally, may be vesicular. Mild-to-moderate pruritus may be present. Systemic manifestations are unusual and include fever, lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. Unusual presentations of GCS have been reported, either by atypical clinical characteristics or location of the skin lesions. Two cases of GCS confined to the face have been reported, as well as a patient with typical GCS lesions accompanied by plantar erythema and desquamation.4–6 Age, health and vaccination status have been pointed out as potential influencers of clinical presentation.7

GCS primarily affects infants aged between one and six years, rarely occurring in adults.1,2 Although it usually occurs in association with a viral illness, most often by Hepatitis B virus or Epstein–Barr virus, it is occasionally associated with other pathogens or vaccinations. The precise pathogenesis of GCS is not clear, but it is presumed to be immunologically mediated. Furthermore, it appears that GCS is associated with atopy, due to its increased prevalence in patients with personal and/or family history of atopic disease.3,4 The diagnosis is mainly clinical, with no characteristic laboratory features nor specific findings in skin biopsy. Patients may have modest lymphocytosis or lymphopenia and liver enzymes may be elevated. Histopathologic findings can include mild epidermal acanthosis and spongiosis with focal paraketatosis, as well as papillary dermis edema and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.1 The disease has a benign course, with spontaneous resolution usually within 2–6 weeks. Post-inflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation may follow resolution of the skin lesions, but permanent scarring is uncommon. Symptomatic treatment of the associated pruritus usually suffices.1–3

We highlight the importance of considering GCS in the differential diagnosis of papular eruptions, even in adult patients. During the current COVID-19 pandemic, the reported cases regarding dermatologic manifestations associated to SARS-CoV-2 have been increasing, some of which concern unexpected groups of patients or clinical contexts. There have been two reported cases of GCS in patients with confirmed COVID-19.8,9 We now report a unique case of this dermatological entity, mainly distributed in atypical locations and associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, so far not described in the literature.

FundingThere are no funding sources of this article.