Facial angiofibromas are hamartomatous growths that are closely associated with tuberous sclerosis complex and, in fact, they constitute one of the main diagnostic criteria for that disease. These lesions composed of blood vessels and fibrous tissue appear on the face at an early age. Since they have important physical and psychological repercussions for patients, several treatment options have been used to remove them or improve their appearance. However, the lack of treatment guidelines prevents us from developing a common protocol for patients with this condition.

The present article aims to review the treatments for facial angiofibromas used to date and to propose a new evidence-based treatment protocol.

Los angiofibromas faciales son tumoraciones hamartomatosas íntimamente relacionadas con el complejo de la esclerosis tuberosa, y representan uno de los criterios mayores para el diagnóstico de la enfermedad. Su aparición desde edades tempranas en la región facial, así como su naturaleza fibrovascular, producen importantes repercusiones físicas y psicológicas en estos pacientes, lo que ha motivado la utilización de múltiples tratamientos para su eliminación o mejora. Sin embargo, no existen guías de tratamiento que permitan establecer un protocolo de actuación común en este tipo de pacientes.

El objetivo de este artículo es revisar los tratamientos utilizados hasta la fecha para los angiofibromas faciales en función de la evidencia científica demostrada e intentar aportar un protocolo terapéutico.

Tuberous sclerosis is a genodermatosis with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and variable expression. It is characterized by the formation of multisystemic hamartomas.1 The tumor suppressor genes TSC1 and TSC2 encode the proteins hamartin and tuberin, which form a complex that inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a fundamental protein in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation. The broad clinical spectrum of tuberous sclerosis is due to the presence of mutations in TSC1 and TSC2, which cause dysregulation of mTOR signaling, giving rise to uncontrolled cell proliferation and, consequently, the appearance of hamartomas in different parts of the body, including the skin, brain, kidneys, lungs, heart, and eyes.2

Cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis include facial angiofibromas, hypopigmented macules (“ash leaf spots”), shagreen patches, periungual fibromas, and the recently described folliculocystic and collagen hamartoma.3

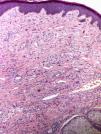

In 1880, Bourneville4 included the facial lesions presented by patients with tuberous sclerosis under the name acne rosacea; these lesions, together with mental retardation and convulsions, formed a characteristic clinical triad. Pringle5 later coined the term adenoma sebaceum to describe these growths. With the development of histopathology, this term was abandoned because it was seen as confusing: the lesions are not an adenomatous proliferation of sebaceous glands but rather a dermal proliferation of fibroblasts and collagen fibers accompanied by an increase in dilated blood vessels with irregular surfaces6 (Fig. 1). Because of these morphological findings, the term facial angiofibroma has replaced the older, erroneous terms.

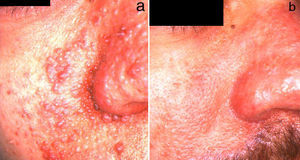

Facial angiofibromas are hamartomatous growths that appear as multiple small, pinkish, erythematous papules that tend to coalesce to form plaques. They usually appear on the central part of the face bilaterally and symmetrically, and they characteristically affect the nasolabial folds. Isolated cases of unilateral facial angiofibromas, in some cases associated with other manifestations of tuberous sclerosis, have been reported.7,8 These cases could correspond to segmental forms of tuberous sclerosis.

Facial angiofibromas appear in up to 80% of patients with tuberous sclerosis and are a major diagnostic criterion for tuberous sclerosis.9 They begin to appear between 2 and 5 years of age and progressively increase in number and size before stabilizing after adolescence.

Although facial angiofibromas are closely related to tuberous sclerosis, they can appear as manifestations of other entities, such as neurofibromatosis type 2,10 Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome,11 and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1.12 Exceptionally, multiple bilateral facial angiofibromas not associated with any systemic manifestations can occur.13

Because facial angiofibromas have both physical repercussions (nasal obstruction, bleeding after minor trauma) and psychological repercussions (emotional and self-image problems),14,15 multiple treatments have been used to eliminate these growths and increase patients’ quality of life.

Material and MethodsWe conducted a literature search using the MEDLINE, EMBASE, Medicina en Español (MEDES), Índice Médico Español (IME), and Cochrane Library databases. We reviewed articles in English and Spanish published between 1992 and August 2012, as well as their references. We also consulted ongoing clinical trials at the website http://www.clinicaltrial.gov.

ResultsThere has only been 1 randomized controlled trial evaluating the treatment of facial angiofibromas associated with tuberous sclerosis. The rest of the available treatments are based on data from small case series and isolated case reports. In addition, all methods for measuring severity and response to treatment are subjective, and only 1 method has yielded data with intra- and interobserver reliability.16

Physical TreatmentsSince tuberous sclerosis was first described, various physical treatments have been used to correct facial angiofibromas. All of these treatment modalities are invasive and painful and therefore require the use of anesthesia. Although they can yield good results, especially in patients with severe facial angiofibromas, these treatments can lead to complications such as hypertrophic scars, pigmentation disorders, and postoperative infections. Additionally, their success depends to a large extent on the dermatologist's expertise and prior experience with the technique.

Radiofrequency AblationRadiofrequency ablation has been used, with good results, in 2 adult patients with dark skin phototypes, although postinflammatory hyperpigmentation occurred and the lesions reappeared.17,18

CryotherapyThere have been anecdotal reports of cryotherapy being used to treat facial angiofibromas in 3 isolated cases.19,20 This method is inexpensive and easy to apply and does not require anesthesia, but it requires several sessions and patient collaboration—which is not possible in many cases because of the psychological alterations associated with tuberous sclerosis—and yields limited results.

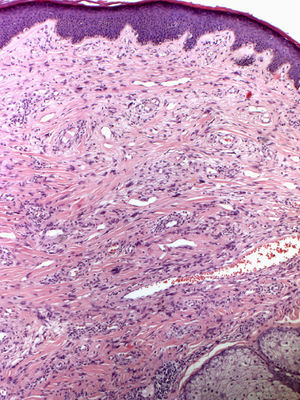

ElectrocoagulationElectrocoagulation has been used to treat large facial angiofibromas, with good results (Fig. 2). However, the quality of the results depends to a large extent on the dermatologist's experience, and the risk of scarring and other postoperative complications is high. More specific techniques that make it possible to control the electrical power more precisely have therefore been developed. Capurro et al.21 obtained good long-term results in a patient with facial angiofibromas by using timed surgery, an electrosurgical procedure that allows the physician to set the energy and emission-time parameters.

DermabrasionDermabrasion has been used by several authors, with good results.22–25 In this technique, the largest lesions are treated with shave excision before the remaining lesions are treated with dermabrasion under general anesthesia. The risk of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, scarring, and recurrence in the medium to long term is very high. To avoid these complications and minimize the healing time, some authors have proposed the use of cultured epithelial autografts26 or artificial dermis.27 Hori et al.26 used cultured autologous epidermal grafts in 5 adults following the removal of multiple large facial angiofibromas via shave excisions and dermabrasion. Reepithelization was rapid and there were no complications. However, because the process requires general anesthesia and the full cooperation of the patient to ensure graft survival, several patients had to be sedated during the postoperative period. Some regrowth of the lesions occurred 4 to 5 years after the procedure and retreatment was necessary in 2 patients.

Laser TreatmentsThe development of laser treatments and their introduction in dermatology has allowed a more precise approach to treating various diseases, with excellent results and fewer adverse effects.

Various types of laser have been used in the treatment of facial angiofibromas. The first types of laser to be used were ablative argon28,29 and carbon dioxide (CO2) lasers.30,31 With the introduction of new equipment such as copper vapor lasers,32 argon lasers, potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) lasers,33,34 and, especially, pulsed dye lasers (PDL),35–38 numerous authors began to treat facial angiofibromas with these types of lasers using the principle of selective photothermolysis. Later, PDL started to be used in combination with other light sources such as with 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy39 and fractional resurfacing,40 with good results. Table 1 summarizes all of the studies that have reported more than 2 cases of facial angiofibromas treated with various types of laser.34,35,37,39–42

Case Series of Patients With Facial Angiofibromas Treated With Laser Therapy.

| Study | No. of Patients | Type of Laser | Male/Female, No. | Mean Age (Range) | Mean No. of Sessions (Range) | Response (%) | Follow-up | Adverse Effects |

| Boixeda et al.35 (1994) | 10 | CO2 (7) | 6/4 | 16.5 (10-23) | 1 | Excellent (70) | 4-20 mo | Hyperpigmentation (10%) |

| Argon (2) | Good (30) | No recurrence | Hypertrophic scars (30%) | |||||

| PDL (1) | ||||||||

| Tope et al.34 (2001) | 5 | KTP | 1/4 | - | 1-5 | Total (100) | 6-12 mo | Hyperpigmentation |

| No recurrence | Hypopigmentation | |||||||

| Bittencourt et al.42 (2001) | 10 | CO2 | 7/3 | 30.3 (17-64) | 1 | Excellent (60) | 24 mo | Hypopigmentation (20%) |

| Good (20) | Recurrence: 80% | Acneiform eruptions (30%) | ||||||

| Moderate (10) | Hyperpigmentation (10%) | |||||||

| Minimal (10) | ||||||||

| Papadavid et al.37 (2002) | 29 | CO2 (13) | 14/15 | 22.6 (9-48) | 2.8 (1-6) | Excellent (82.8) | 24-60 mo | CO2: |

| PDL (12) | Moderate (10.3) | Recurrence: 3.4% | -Hypertrophic scars (53.8%) | |||||

| CO2+PDL (4) | Poor (6.9) | -Hyperpigmentation: (15.4%) | ||||||

| PDL: none | ||||||||

| Belmar et al.41 (2005) | 23 | CO2 | 7/16 | 22.5 (12-39) | 1.9 (1-3) | Excellent (39.1) | 6-120 mo | Overall rate: 21.9% |

| Good (56.5) | Recurrence: 60.9% | |||||||

| Moderate (4.3) | ||||||||

| Weinberger et al.39 (2009) | 6 | PDT+PDL | 4/2 | 22.6 (10-33) | 2.5 (1-4) | ↓ Erythema (100) | 48 mo | No |

| ↓ Size (100) | Recurrence: 33% | |||||||

| ↓ Number (33) | ||||||||

| Weiss et al.40 (2010) | 3 | PDL+AFR | 3/0 | 20 (13-30) | 1.6 (1-2) | ↓ Erythema (100) | 3-10 mo | No |

| ↓ Size (100) | No recurrence |

Abbreviations: AFR: ablative fractional resurfacing; CO2, carbon dioxide laser; KTP, potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser; PDL, pulsed dye laser; PDT, photodynamic therapy.

CO2 lasers have been shown to be effective in both the continuous-wave and superpulsed modes of operation, with similar results (Fig. 3). The ablative effect of CO2 lasers has made it possible to treat larger facial angiofibromas and carry out deeper resurfacing, leading to more effective treatment, but with more complications, such as hypertrophic scarring, which can appear in up to 53.8% of cases.37 General anesthesia is usually necessary, although the procedure can be performed under local anesthesia in some cases of localized lesions. In the study with the longest follow-up period carried out to date,41 lesions recurred in 60.9% of patients and the mean recurrence time was 3 years. Recurrence began as an increase in the volume of the lesions followed by an increase in the number of lesions, and patients younger than 20 years of age had earlier recurrences than older patients. Bittencourt et al.42 treated 10 patients with CO2 laser and classified them in 3 groups according to trends in response and long-term maintenance. Two groups of patients showed a good response to treatment at 6 months; long-term efficacy was maintained in 1 group and lesions reappeared in the other. The third group of patients invariably showed a poor response.

PDL has been used to treat facial angiofibromas because of the major vascular component of these lesions. Papadavid et al.37 obtained good results in 16 patients who had facial angiofibromas with a predominantly vascular component. Improvement in erythema was observed in more than 90% of patients. However, no decrease in the fibrous component was observed, and as a result more than half of the patients had to be treated with electrosurgery in addition to CO2 laser. The PDL treatment achieved the best results in children, who showed no signs of recurrence after 2 to 5 years of follow-up.

Although no clinical trials or prospective studies have been carried out, the trends observed in the literature suggest that patients with facial angiofibromas with a large vascular component and lower volume could benefit from PDL treatment, whereas CO2 laser would be especially useful in patients whose lesions have a more pronounced fibrous component.

Medical TreatmentsAlthough physical treatments have generally been selected to treat facial angiofibromas, some drugs have also been used in isolated cases. The use of new topical formulations has recently opened up a new therapeutic perspective in the treatment of facial angiofibromas.

TranilastTranilast (N-[3,4-dimethoxycinnamoyl]-anthranilic acid) is an antiallergic drug that was approved in 1982 for use in Japan and South Korea in the treatment of bronchial asthma. The discovery of the drug's antiproliferative properties—inhibition of growth factors such as transforming growth factor-β, reduction of mast-cell cytokine secretion, and inhibition of metalloproteinase secretion in the extracellular matrix—provided a rationale for its use in the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars.43

Wang et al.44 treated 3 adults with tuberous sclerosis with oral tranilast at a dose that increased from 1 to 5mg/kg/d for 3 years. Erythema improved and the size of the facial angiofibromas decreased in 2 patients. A reduction in periungual fibromas was observed in 2 patients, although none of the patients showed improvement in achromic macules. The authors observed no adverse effects. Because the patients were not followed up, it is not known whether the lesions recurred after tranilast was withdrawn.

PodophyllotoxinPodophyllotoxin is an alkaloid derivative that has been used for years in the treatment of genital warts and actinic keratoses. Only 1 case has been reported of podophyllotoxin being used in the treatment of facial angiofibromas associated with tuberous sclerosis.45 A 25% podophyllotoxin solution was applied once monthly for 3 months and a partial response was achieved. There were no adverse effects except a burning sensation on application of the treatment.

Sirolimus (Rapamycin)Sirolimus is a molecule that belongs to a group known as mTOR inhibitors. It is currently approved for use in the prevention of organ rejection in patients who have undergone a kidney transplant and in drug-eluting coronary stents.

The molecular mechanism of action of sirolimus is partially understood. Sirolimus induces immunosuppression by blocking the cell cycle of T cells at the transition from the G1 phase to the S phase, thereby preventing T cell activation and antibody production. The antitumor effect of sirolimus is based on its ability to normalize abnormally increased mTOR signaling in tumor cells and inhibit angiogenesis by causing levels of vascular endothelial growth factor to decrease.46

Because of the aforementioned antiproliferative effects of sirolimus and its analogs (everolimus, temsirolimus, ridaforolimus), clinical trials of the drug in the treatment of various tumors have been carried out.46–54

Hofbauer et al.55 and Tarasewicz et al.56 reported considerable improvement in facial angiofibromas in 2 patients with tuberous sclerosis who had undergone a kidney transplant following oral administration of sirolimus as a prophylaxis against rejection. This effect was corroborated in a subsequent clinical trial46 in which the authors observed subjective improvement of facial angiofibromas in 57% of patients after 52 weeks of treatment with oral sirolimus. However, because of the potential adverse effects of sirolimus, oral use of this drug would not be justified to treat facial angiofibromas in patients with no other associated abnormalities.

Haemel et al.57 reported the first case of facial angiofibromas treated with topical sirolimus. Supported by an animal model58 and safety data from a clinical trial carried out in patients with psoriasis,59 the authors developed a 1% sirolimus ointment. A decrease in lesion size and erythema was observed after 3 months of treatment with the ointment. A further 59 cases with different dosage regimens and results have subsequently been reported.16,57,60–67

Because of the wide range of formulations and dosages that have been used, and the lack of common measurement systems for evaluating response to treatment, it is extraordinarily difficult to interpret the data from these studies (Table 2). Only in 2 studies16,67 have systematized scales been used to assess erythema, size, extent, and prominence of facial angiofibromas and, of these scales, only the Facial Angiofibroma Severity Index has yielded data with intra- and interobserver reliability.16

Articles About Treatment of Facial Angiofibromas With Topical Sirolimus.

| Author (Year) | No. of Patients | Age, Mean, y | Male/Female, No. | Sirolimus Formulation | Application Regimen | Follow-up, wk | Efficacy | Adverse Effects | Sirolimus Plasma Levels |

| Haemel et al.57 (2010) | 1 | 16 | 1/0 | 1% ointment | 1/12h | 12 | SIR | No | Undetectable |

| Kaufman et al.62 (2012) | 2 | 13.5 | 2/0 | Oral solution+emollient | 1/24h | 12 | SIR | No | Not tested |

| Wataya-Kaneda et al.67 (2011) | 9 | 17 | 3/6 | 0.2% sirolimus in 0.03% tacrolimus | 1/12h | 16 | Mean (SD) final score: 2.61 (1.5-4) | No | Undetectable 9/9 |

| 0.03% tacrolimus | |||||||||

| Mutizwa et al.64 (2011) | 2 | 20.5 | 2/0 | Oral solution | 1/12h | 10 | SIR | Local irritation 2/2 | Undetectable 2/2 |

| Salido et al.16 (2012) | 10 | 13.5 | 5/5 | 0.4% ointment | 3/wk | 36 | Mean improvement (FASI): 60.2% | No | Undetectable 10/10 |

| DeKlotz et al.60 (2011) | 1 | - | - | 1% ointment | 1/12h | 4 | SIR | No | Not tested |

| Valeron-Almazan et al.66 (2012) | 1 | 27 | 1/0 | Oral solution | 1/12h | 12 | SIR | No | Not tested |

| Truchuelo et al.65 (2012) | 1 | 11 | 1/0 | 1% sirolimus+emollient | 1/24h | 4 | SIR | No | Undetectable |

| Foster et al.61 (2012) | 4 | 11.3 | 2/2 | 0.1% ointment | 1/12h | 24 | 75% MSI | Local irritation 2/4 | Undetectable 3/4 |

| Oral solution | |||||||||

| Koenig et al.63 (2012) | 28 | 23 | 15/13 | 0.003% sirolimus+PVDF | 1/24h | 24 | SIP | Local irritation 2/28 | Undetectable 23/23 |

| 0.015% sirolimus+PVDF | Sirolimus: 73% | ||||||||

| -PVDF | PVDF: 38% |

Abbreviations: FASI, Facial Angiofibroma Severity Index; PVDF, polyvinylidene fluoride; SIP, subjective improvement assessed by patient; SIR, subjective improvement assessed by researcher.

Wataya-Kaneda et al.67 carried out the first controlled study of topical sirolimus. The authors evaluated the response of 9 patients who were treated with a 0.03% tacrolimus ointment on half of the face and with 0.03% tacrolimus ointment containing 0.2% rapamycin on the other half. The authors quantified the effectiveness of the treatment by tallying partial scores assigned for the observed improvement in the erythema, size, and thickness of the facial angiofibromas. A score of 2 points was assigned for an improvement of more than 80%, 1 point for improvement of 50% to 80%, and 0.5 points for improvement of 20% to 50%. The final mean score for the 9 patients was 0.5 for the area treated with tacrolimus only and 2.6 for the area treated with sirolimus (P<.001).

In a recent controlled clinical trial,63 28 patients were treated with a formulation containing sirolimus and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), an agglutinating polymer used as a vehicle to make the formulation more occlusive and favor the absorption of the active ingredient. Subjects were randomized and assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups: 0.015% sirolimus, 0.003% sirolimus, or PVDF only. The formulation was applied once daily for 24 weeks. No statistically significant differences between the treatment groups were found. However, of the 23 patients who completed the study, 73% in the treatment groups reported that they “got better” while using the treatment versus 38% in the placebo group. None of the patients had detectable sirolimus plasma levels in the blood or abnormalities in their complete blood counts. One patient had an episode of aspiration during a seizure and developed pneumonia, which subsequently progressed to septic shock. However, this study had important limitations. The authors did not define the initial severity of the lesions, use researcher-assessed methods for measuring efficacy, or carry out intermediate controls during treatment in order to monitor clinical course in the patients.

Given that no commercialized topical sirolimus preparations exist, physicians have developed compounds at different concentrations by crushing and sifting commercially available sirolimus tablets (Rapamune).60 The use of sirolimus in powder form has considerably improved the physical properties of sirolimus formulations and reduced their cost.68 Some authors have applied the commercially available oral sirolimus solution (1mg/ml) to facial angiofibromas, either alone61,64–66 or in combination with emollients.62

Topical treatment with sirolimus has been found to decrease the size of facial angiofibromas and accelerate the resolution of erythema (Fig. 4), and it has been suggested that this treatment is more effective in younger patients.60,61 However, studies with larger sample sizes are needed in order to substantiate the observed trends.

The literature on sirolimus shows that the drug has a good safety profile. Only 6 cases of local irritation have been reported. Of these cases, 4 were related to the direct application of the oral sirolimus solution (1mg/ml) and the other 2 were related to the sirolimus-PVDF formulation. No systemic adverse effects have been observed and the sirolimus plasma levels have been below the limits of detection in 49 of the 50 patients who were tested. Sirolimus has only been found in the blood of 1 patient, and the amount detected was well below therapeutic levels and the toxicity range.61

Because the use of sirolimus and everolimus has been associated with the possible impairment of the wound healing process,69,70 it has been recommended that topical sirolimus not be applied on wounds.

It was initially suggested that the incidence of lymphomas and skin cancer is higher than normal in patients treated with oral sirolimus.71 However, this claim has been refuted by various studies that have shown that patients who have received long-term treatment with sirolimus have a lower overall incidence of cancer72 as well as lower rates of lymphoma73 and nonmelanoma skin cancer,74 specifically.

There are no data on the possibility of facial angiofibromas growing back after suspension of treatment. Only 1 study has reported recurrence of erythema (1 month after withdrawal of the formula).67

Topical sirolimus has also been used in 2 patients with hypomelanotic macules associated with tuberous sclerosis, and clearance of the lesions was achieved after 3 months of treatment.75

Other mTOR inhibitors have also been shown to be effective in the treatment of facial angiofibromas. In a clinical trial of everolimus for the treatment of subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas, 13 of 15 patients reported subjective improvement of facial angiofibromas.50 There have been no studies on the possible topical use of everolimus.

The development of new mTOR inhibitors such as temsirolimus and ridaforolimus, currently used in the treatment of various types of cancer,48,49 could play a role in controlling cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis.

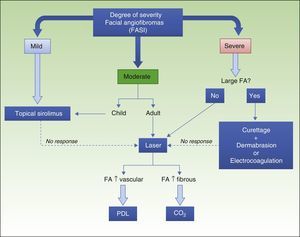

ConclusionsAt present, it remains difficult to try to systematize the treatments used for facial angiofibromas. Because of the low prevalence of these growths, clinical trials have been scarce and therapeutic alternatives have only been used in isolated cases and small case series.

The treatments traditionally used for facial angiofibromas involve invasive techniques and the possibility of complications and permanent sequelae. Surgery, electrocoagulation, cryotherapy, chemical peelings, and laser therapy have been the most commonly used treatments. The introduction of sirolimus in recent years has revolutionized the treatment of facial angiofibromas. Topical use of sirolimus, to avoid the potential adverse effects of systemic use, has been shown to be very safe. Treatment with topical sirolimus has so far yielded encouraging results in terms of the drug's efficacy in reducing erythema and lesion size.

In our experience with topical sirolimus, we have observed a rapid response to treatment in practically all patients. In just a few days, erythema subsides and the size and extent of the lesions subsequently decrease progressively. Our best results have been achieved in young patients with small, low-volume facial angiofibromas; in some such patients, complete resolution of the lesions has been achieved with treatment. In adults with lesions that have a more pronounced fibrous component, the response is slower and the results are inferior. The stabilization of facial angiofibromas after adolescence could play a role in the more favorable response seen in younger patients. Other authors have reported the same findings.61 It is therefore possible to define a profile of potentially good responders: young patients with facial angiofibromas in which the erythematous component is more developed than the fibrous component and lesions that are not very elevated.

Physical treatments remain in use today despite their potential for complications. Patients with severely disfiguring facial angiofibromas can obtain the greatest benefit from these techniques. Although the results tend to be satisfactory, the possibility of recurrence is quite high. The combination of laser therapy or dermabrasion and topical sirolimus for maintenance after the lesions have healed completely could be very useful in patients with severely disfiguring facial angiofibromas.

Because public institutions and private entities have been making considerable efforts to control pharmaceutical expenses, the high cost of these treatments can be a barrier to their use. The per-patient monthly cost of this treatment was initially very high due to the concentrations and regimens used and the fact that the formulations were prepared using oral sirolimus tablets. Because the active ingredient has since became available in powder form through pharmaceutical laboratories at a much lower price and the concentrations used have decreased, the cost of preparing the formulation is now much lower. As a result, this treatment is now very cost-effective and feasible for ongoing use in patients with facial angiofibromas.

In contrast, laser treatments are expensive because they require special equipment, an operating room equipped for general anesthesia, and posttreatment hospitalization. The high cost of laser treatment is a barrier to access for many patients.

The introduction of topical sirolimus has made it possible to significantly improve the appearance of patients with facial angiofibromas and avoid the complications that can arise from conventional treatments. On the basis of the published data and the experience of our group, we propose an algorithm for the management of facial angiofibromas (Fig. 5). The clinical trials currently underway76 and future comparative trials will provide additional scientific evidence regarding safety and efficacy, making it possible to establish more precise treatment indications.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for the purpose of this study.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their hospitals concerning the publication of patient data and that all patients included in this study were appropriately informed and gave their written informed consent.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data are disclosed in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We are grateful to Dr Juan Salvatierra of the pathology department at Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía.

Please cite this article as: Salido-Vallejo R, Garnacho-Saucedo G, Moreno-Giménez JC. Opciones terapéuticas actuales para los angiofibromas faciales. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:558–568.