The prevalence of contact allergy to different compounds can vary according to the population studied, the technique used, and the materials employed in patch tests. The Spanish Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy Research Group (GEIDAC) has proposed a panel of 29 allergens for use in patients with suspected allergic contact dermatitis.

ObjectiveTo determine the prevalence of contact sensitization in a group of Spanish patients and to analyze potential associations with sociodemographic and clinical variables (sex, age, site of lesions, occupation, and diagnosis of atopic dermatitis).

Materials and methodsA retrospective study of patients with suspected contact dermatitis was undertaken at Hospital Costa del Sol in Marbella, Spain, for the period between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2010; 839 patients were included in the analysis. Patch tests were carried out with 34 allergens, including the 29 compounds that comprise the Spanish standard panel proposed by the GEIDAC.

ResultsSensitization to at least 1 allergen in the panel was observed in 48% of patients. Women had a higher frequency of sensitization than men (56.9% vs 33.1%). The hands were the most commonly affected site (36.1%). The most frequently involved allergens were nickel sulfate (25.9%), potassium dichromate (7.6%), thiomersal (5.1%), cobalt chloride (4.5%), and fragrance mix I (3.8%). In contrast, preservatives such as paraben mix (0.1%), imidazolidinyl urea (0.1%), diazolidinyl urea (0.2%), and quinoline mix (0.2%) had low rates of sensitization. Sensitization to sesquiterpene lactones and methyldibromo glutaronitrile (euxyl K 400) were not observed.

ConclusionsOur results are similar to those previously reported for Spanish patients. The low level of sensitization to certain allergens such as most preservatives and sesquiterpene lactones may suggest that their use in standard patch test series should be reconsidered.

La prevalencia de la alergia de contacto a los diferentes compuestos puede variar dependiendo de la población estudiada, de la técnica y del material empleado en las pruebas epicutáneas. En España el Grupo Español de Investigación en Dermatitis de Contacto y Alergia Cutánea (GEIDAC) ha propuesto una batería de 29 alérgenos para estudiar a los pacientes con sospecha de dermatitis de contacto alérgica.

Material y métodosAnálisis retrospectivo de 839 pacientes con sospecha de dermatitis de contacto, realizado en el Hospital Costa del Sol desde el 1 de enero de 2005 hasta el 31 de diciembre de 2010. Para ello se utilizaron pruebas epicutáneas estándar de 34 alérgenos en las que estuvieron incluidos los 29 compuestos de la batería estándar española propuesta por el GEIDAC.

ObjetivoValorar la prevalencia de la sensibilización de contacto entre los pacientes estudiados y estudiar su asociación con factores sociodemográficos (sexo, edad, localización, ocupación) y clínicos (dermatitis atópica).

ResultadosEl 48% de los pacientes presentó sensibilización al menos a uno de los alérgenos testados. Las mujeres presentaron una frecuencia de sensibilización más elevada que los hombres (56,9 vs. 33,1%). La localización afectada con mayor frecuencia fue la mano (36,1%). Los alérgenos más frecuentes fueron sulfato de níquel (25,9%), dicromato potásico (7,6%), tiomersal (5,1%), cloruro de cobalto (4,5%) y mezcla de fragancias I (3,8%). Por el contrario, se detectó una baja frecuencia de sensibilización a conservantes como mezcla de parabenos (0,1%), imidazolidinil urea (0,1%), diazolidinil urea (0,2%) y mezcla de quinoleínas (0,2%). No se registraron sensibilizaciones para lactonas sesquiterpénicas y metildibromoglutaronitrilo (euxyl K400).

ConclusionesNuestros resultados son similares a los previamente publicados a nivel nacional. La baja sensibilización a ciertos alérgenos, como la mayoría de conservantes y las lactonas sesquiterpénicas, podría hacer necesario reconsiderar su utilidad como alérgenos en futuras series estándar.

Contact dermatitis affects between 1% and 10% of the population1 and is a common reason for consultation. The incidence of allergic contact dermatitis in particular has grown in industrialized countries, as has the number of potential allergens. Skin patch tests are an essential tool for diagnosing allergic contact dermatitis and identifying the offending chemicals.2 Most centers use standard series of allergens for this purpose. These series contain the most common allergens for the local population and can vary considerably from one country to the next.3,4 The series recommended by the Spanish Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy Research Group (GEIDAC) currently contains 29 allergens.5

No epidemiological studies of sensitization to contact allergens among the general population in the health care area of Costa del Sol Occidental in Malaga have been published to date. The aims of the present study were to describe our experience with patch testing in this health care area and to analyze the association between the development of contact sensitization and various epidemiological and clinical variables.

Materials and MethodsWe retrospectively analyzed all patients who underwent patch testing at the skin allergy unit of Hospital Costa del Sol in Marbella, Spain between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2010. We recorded age, sex, area of the skin affected, diagnosis, and personal history of atopy. The patient's occupation was also noted when this information was available. The tests were performed with a standard series of 34 allergens, including the 29 compounds recommended by the GEIDAC. All the patients were tested with approved allergens (T.R.U.E TEST and Martí-Tor) applied using Curatest patch strips. The tests were performed using the standard procedure, and patients were instructed to avoid excessive movement, activities that cause sweating, and bathing. Readings were taken at 48 and 96hours, although only the positive results at 96hours were included in the analysis. Patients who developed erythematous papular or vesicular lesions were considered to have positive reactions; the intensity of the reaction was graded as +, ++, or +++ according to the recommendations of the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Only clearly positive or negative reactions were included in the final analysis. In other words, equivocal and irritant reactions (<1%) were not considered.

The clinical relevance of the results, assessed on the basis of positivity, clinical manifestations, and history of exposure, was also recorded for each patient.

Statistical AnalysisWe analyzed the frequency distribution of all the study variables and built a forward stepwise multiple logistic regression model for the dependent variable (presence or absence of sensitization), with an entry criterion of P=.05 and an exit criterion of P=0.1. Odds ratios were presented with 95% CIs. Statistical significance was set at a level of P less than .05, and data were analyzed using SPSS version 15.0.

ResultsStudy PopulationPatch tests were performed in 839 patients: 531 women (63.3%) and 308 men (36.8%). The age range was 12–90 years, with a mean of 45 years. A positive reaction to at least 1 allergen was observed in 404 patients (48.2%) while 99 patients (22.8%) were sensitized to 2 allergens and 68 (16.9%) were sensitized to 3 or more.

Contact AllergensThe most common contact allergens in our series were nickel sulfate (25.9%), potassium dichromate (7.6%), thiomersal (5.1%), cobalt chloride (4.5%), and fragrance mix I (3.8%). The frequency and relevance of positive reactions to each allergen are shown in Table 1.

Patch Test Results and Distribution of Positive Reactions by Sex.a

| Allergen | Females | % | Males | % | Total | % | Relevance, % |

| Nickel sulfate (5% in pet) | 200 | 37.7 | 17 | 5.5 | 217 | 25.9 | 92.2 |

| Potassium dichromate (0.5% in pet) | 33 | 6.2 | 31 | 10.1 | 64 | 7.6 | 85.9 |

| Thiomersal (0.1% in pet) | 37 | 7.0 | 6 | 1.9 | 43 | 5.1 | 4.6 |

| Cobalt chloride (1% in pet) | 28 | 5.3 | 10 | 3.2 | 38 | 4.5 | 52.6 |

| Fragrance mix (5% in pet) | 21 | 4.0 | 11 | 3.6 | 32 | 3.8 | 56.2 |

| Kathon CGb (0.01% in water) | 25 | 4.7 | 6 | 1.9 | 31 | 3.7 | 74.2 |

| Paraphenylenediamine (1% in pet) | 24 | 4.5 | 5 | 1.6 | 29 | 3.5 | 75.8 |

| p-tert Butylphenol formaldehyde resin (1% in pet) | 14 | 2.6 | 11 | 3.6 | 25 | 3.0 | 80.0 |

| Carba mix (3% in pet) | 10 | 1.9 | 13 | 4.2 | 23 | 2.7 | 86.7 |

| Mercury (0.5% in pet) | 12 | 2.3 | 8 | 2.6 | 20 | 2.4 | 5.0 |

| Thiuram mix (1% in pet) | 11 | 2.1 | 9 | 2.9 | 20 | 2.4 | 90.0 |

| Colophony (20% in pet) | 8 | 1.5 | 8 | 2.6 | 16 | 1.9 | 18.7 |

| Caine mix (10% in pet) | 11 | 2.1 | 5 | 1.6 | 16 | 1.9 | 45.6 |

| Black rubber mix (0.6% in pet) | 11 | 2.1 | 3 | 1.0 | 14 | 1.7 | 92.8 |

| Ethylenediamine (1% in pet) | 7 | 1.3 | 4 | 1.3 | 11 | 1.3 | 54.5 |

| Quaternium 15 (1% in pet) | 11 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 1.3 | 54.5 |

| Tixocortol pivalate (0.1% in pet) | 3 | 0.6 | 4 | 1.3 | 7 | 0.8 | 50.0 |

| Epoxy resin (1% in pet) | 2 | 0.4 | 5 | 1.6 | 7 | 0.8 | 85.7 |

| Wool alcohols (30% in pet) | 2 | 0.4 | 4 | 1.3 | 6 | 0.7 | 50.0 |

| Balsam of Peru (25% in pet) | 5 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.7 | 66.6 |

| IPPDc,d (0.1% in pet) | 4 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.7 | 83.3 |

| Hydrocortisonec (1% in pet) | 3 | 0.6 | 3 | 1.0 | 6 | 0.7 | 66.6 |

| Formaldehyde (1% in water) | 5 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.6 | 20.0 |

| Mercaptobenzothiazole (2% in pet) | 3 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.6 | 80.0 |

| Budesonide (0.1% in pet) | 2 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.5 | 20.0 |

| Neomycin sulfate (20% in pet) | 1 | 0.2 | 3 | 1.0 | 4 | 0.5 | 50.0 |

| Mercapto mix (1% in pet) | 2 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.4 | 100.0 |

| Clioquinolc,e (5% in pet) | 2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Diazolidinil ureac (2% in pet) | 2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Quinoline mix (6% in pet) | 2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.2 | 50.0 |

| Imidazolidinil ureac (2% in pet) | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Paraben mix (16% in pet) | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.1 | 100.0 |

| Euxyl K400 (1.5% in pet) | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | – |

| Lactones (0.1% in pet) | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | – |

Abbreviations: IPPD indicates N-isopropyl-N′-phenyl-paraphenylenediamine; pet, petrolatum.

The MOAHLFA index (male, occupational dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, hand, face, leg, and age >40 years) is a rapid tool for evaluating the demographic profile of a population.

Table 2 shows the MOAHLFA index for our series as a whole and for the groups of patients sensitized to the 5 most common allergens.

MOAHLFAa Index for the Whole series and for the 5 Most Common Allergens.

| Total | Nickel Sulfate | Potassium Dichromate | Thiomersal | Cobalt Chloride | Fragrance Mix | |

| Male | 36.7% | 26.3% | 48.4% | 34.4% | 7.8% | 14.0% |

| Dermatitis | ||||||

| Occupational | 18.8% | 14.3% | 13.3% | 28.6% | 16.9% | 45.0% |

| Atopic dermatitis | 15.9% | 18.4% | 4.7% | 21.9% | 12.9% | 20.9% |

| Hands | 36.1% | 21.1% | 23.4% | 37.5% | 30.9% | 60.5% |

| Leg | 9.8% | 21.1% | 18.8% | 6.3% | 7.4% | 7.0% |

| Face | 13.9% | 2.6% | 1.6% | 12.5% | 16.1% | 14.0% |

| Age >40 y | 59.8% | 50.0% | 67.2% | 75.0% | 56.2% | 23.3% |

A positive reaction to at least 1 allergen was observed in more women than men (56.9% vs 33.1%). The most common allergens detected in women were nickel sulfate (37.7%), thiomersal (7.0%), potassium dichromate (6.2%), cobalt chloride (5.3%), and Kathon CG (methylchloroisothiazolinone and methylisothiazolinone) (4.7%). In men, they were potassium dichromate (10.1%), nickel sulfate (5.5%), carba mix (4.2%), fragrance mix I, and p-tert butylphenol formaldehyde resin (each 3.6%).

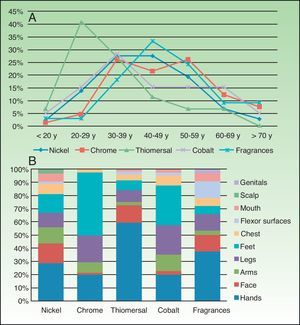

AgeAnalysis by age group showed that the prevalence of contact dermatitis increased with age. This was true for general sensitization and for sensitization to the most common allergens. Sensitization occurred at an earlier age for thiomersal and at a later age for potassium dichromate (Fig. 1).

Occupation and Affected SiteOn analyzing the groups by occupation, contact sensitization was most common in homemakers (17.43%), but domestic workers were sensitized to more allergens on average.

The most common sites affected were the hands and the feet. Almost half (48.0%) of the patients with dermatitis on the feet were sensitized to potassium dichromate (Fig. 1B).

Multivariate AnalysisFemale sex (OR, 3.06; 95% CI, 2.22–4.22; P<.01) and occupational dermatitis (OR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.55–4.25; P<.01) were risk factors for contact sensitization in our series. None of the other variables in the MOAHLFA index were associated with an increased risk of sensitization.

DiscussionWe present the results of the first epidemiological study of contact dermatitis in the health care area of Costa del Sol Occidental in Malaga, Spain. Our findings show a high prevalence of sensitization in the population studied as almost half of the patients tested had a positive reaction to at least 1 allergen in the standard series used at our hospital.The sociodemographic profile of the group studied is very similar to that reported in recent epidemiological studies performed in other parts of Spain, with a predominance of women and patients aged over 40 years. The hands were the most frequently involved site but the associated occupational relevance was very low. We observed a high rate of atopic dermatitis but this was not associated with an increased risk of contact sensitization.6–8

Nickel sulfate was the most common allergen in our series. The prevalence of sensitization to this compound in our health care area is considerably higher than that reported for most countries in Europe and neighboring regions9–13 but similar to that reported for Spain.5,14,15 Several studies have shown that people tend to become sensitized to nickel sulfate at a young age, and that sensitization is associated with the use of earrings.11,16–18 The high prevalence of sensitization to both nickel sulfate and cobalt chloride (the fourth most common allergen) in our series explains why contact sensitization was generally more common in women than in men.

Although sensitization to nickel sulfate increased with age in our series, it was infrequent (2.3%) in patients under 20 years. While this might be related to the application of the European Nickel Directive regulating the amount of nickel sulfate that can be used in jewelry, our study design and small sample size in this age group do not allow us to confirm a downward trend in sensitization to this metal. More observational studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

Occupation is one of the risk factors associated with the development of contact dermatitis, and most individuals (80–90%) with occupational dermatitis have lesions on their hands.19–22 Both occupation and hand dermatitis may actually be associated with an increased risk of sensitization to allergens. Indeed, in our study occupational dermatitis was associated with an increased risk of developing contact sensitization. Our analysis of the frequency of contact sensitization by occupation evidenced that allergic contact dermatitis was most common in homemakers and domestic workers, who had a higher frequency of hand dermatitis (attributable to wet work exposure). Some of the substances handled by the patients are well-known occupational allergens; one example is potassium dichromate, which was the second most common allergen in our series. Most of the patients sensitized to this substance were employed in the construction sector, probably explaining why sensitization to this chemical was more common among men. Nevertheless, almost half of the patients with potassium dichromate sensitization had foot dermatitis, suggesting that footwear might also be an important source of sensitization.

The frequency of sensitization to a particular allergen depends not only on the allergenicity of the compound but also on the level of exposure in the population. For example, we believe that the high prevalence of sensitization to thiomersal (the third most common allergen in our series) is related to its use as a preservative in certain vaccines. While thiomersal is no longer used in vaccines in most countries, it used to be a common preservative. Most of the individuals sensitized to thiomersal in our series were under 30 years of age and would therefore have been routinely vaccinated as children. While the frequency of sensitization to thiomersal in our series is similar to that reported by other studies in Spain, it is much higher than that reported for Scandinavian countries, where its prevalence is less than 2%.11 Nonetheless, the clinical relevance of thiomersal sensitization tends to be low, and it is not a common cause of contact dermatitis.23

The fifth most common allergen in our series was fragrance mix I. The prevalence of sensitization to this mix was similar to that reported by other Spanish studies but lower than that reported by studies conducted in other European countries24 and the United States.25 This could be because the T.R.U.E. TEST series does not include certain fragrance allergens that are a common cause of allergy, such as hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde (Lyral).26,27

There were no positive reactions to the sesquiterpene lactone mix, the only marker of plant allergy in our standard series. A lack of sensitization to this mix has been observed in other epidemiological studies and one might question its value in a standard patch test series. Our analysis also revealed a low frequency of sensitization to the preservatives in our series (clioquinol, paraben mix, methyldibromo glutaronitrile, and quinoline mix). Furthermore, the additional preservatives tested (diazolidinyl urea and imidazolidinyl urea) were also associated with a low rate of sensitization (0.3%) and only marginally improved the sensitivity of the patch tests. Similar findings have been reported.14,28

The Spanish Surveillance System on Contact Allergies (REVAC) also reported a low prevalence of sensitization to these allergens in 2008 and questioned their continued inclusion in the GEIDAC standard series.8 In our study, we observed a high frequency of sensitization to newer preservatives such as Kathon CG, which was the sixth most common allergen in our series.

We tested N-isopropyl-N′-phenyl-paraphenylenediamine (IPPD) and clioquinol separately, even though they are included in the standard GEIDAC series either as individual allergens or in mixes (black rubber mix and quinoline mix, respectively). Although false negatives were obtained for the 2 mixes, clioquinol was associated with a low frequency of sensitization (0.2%) and low clinical relevance. We may thus need to reconsider whether this compound should continue to be included in our standard series. IPPD, on the other hand, was associated with a higher frequency of sensitization and this was clinically relevant in most cases.

In summary, we have shown the prevalence of sensitization to the most common contact allergens in the health care area of Costa del Sol Occidental in Malaga, Spain. Our findings are generally similar to those reported by other Spanish studies. Based on our observation of the low frequency of sensitization and poor clinical relevance for many of the preservatives tested (methyldibromo glutaronitrile, paraben mix, and quinoline mix) and for the sesquiterpene lactone mix, we believe that the possibility of omitting these allergens should be considered when designing a new standard series. The use of the additional allergens tested might also need to be reconsidered as they only slightly improved the overall sensitivity of the standard series. Nevertheless, further multicenter studies are needed to provide evidence to support the inclusion of new allergens or the exclusion of others with little or no value.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Aguilar-Bernier M, et al. Sensibilización de contacto a alérgenos de la serie estándar en el Hospital Costa del Sol: Estudio retrospectivo. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:223–238.