Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) supporting advanced treatments for atopic dermatitis (AD) involve highly selected patients, limiting their generalizability.

ObjectiveTo determine the proportion of adults on advanced systemic therapy for AD in clinical practice who are underrepresented in RCTs and compare the safety and drug survival of these treatments between RCT-eligible and RCT-ineligible patients.

Material and methodsDescriptive and comparative analysis of data from the Spanish Atopic Dermatitis registry BIOBADATOP. Patients were deemed RCT-ineligible if they met, at least, 1 of 8 common exclusion factors: age≥65 years; pregnancy desire, pregnancy desire, pregnancy, or lactation; uncontrolled hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes; chronic kidney disease; cancer diagnosis; liver disease; history of tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis B or C infection; and active or acute infection.

ResultsOf the 366 adults in BIOBADATOP on advanced systemic therapies for AD, 18.3% would be considered ineligible to participate in RCTs. Ineligible patients were older and had more comorbidities than eligible patients. Inclusion of an EASI score<16 at baseline in the sensitivity analysis increased the proportion of ineligible patients to 37.2%. Janus kinase inhibitors were used less often as a first-line therapy in RCT-ineligible patients. Although serious adverse events were significantly more common in ineligible patients, this difference was lost after adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidities.

ConclusionsOverall, 18.3% of real-world patients with AD—and 37.2% including those with EASI<16—are underrepresented in RCTs. Age and comorbidities influence safety outcomes and should be considered when taking treatment decisions and designing RCTs.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, recurrent inflammatory skin disease with an estimated prevalence of 10% in adults and 20% in children.1 Recent advances in our understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms underlying this disease have led to significant improvements in treatment options.2 Thus, a total of 6 novel systemic therapies have emerged for the management of moderate-to-severe AD in recent years, namely 3 Janus kinase [JAK] inhibitors—baricitinib, upadacitinib, and abrocitinib—and 3 biologics—dupilumab, tralokinumab, and lebrikizumab.3 Lebrikizumab was approved in just 2023. Because AD often requires long-term systemic therapy, safety is a critical consideration.

Although the safety and efficacy profile of novel treatments for AD is supported by data from clinical trials, these typically apply strict inclusion and exclusion criteria,4 limiting the generalizability of their findings. Patients with moderate-to-severe AD who do not meet these criteria, for example, but who are eligible for advanced systemic treatments might experience different adverse effects and responses.

Real-world registries are important sources of pharmacovigilance data that can be very useful for monitoring long-term safety and efficacy in diverse patient populations. They may be more representative of the overall population with a given disease as they do not exclude patients based on factors such as age, comorbidities, and concomitant treatments.5,6

The primary endpoint of this study was to quantify the proportion of patients with AD on advanced systemic therapy who are underrepresented in randomized clinical trials (RCTs). Secondary endpoints were to describe the clinical characteristics and treatments in underrepresented patients and compare the risk of adverse events between RCT-eligible and -ineligible patients.

MethodsData for this study were obtained from the Spanish national BIOBADATOP registry, which is a real-world registry that collects information on patients of all ages with AD started on a new systemic therapy (conventional or advanced).7 The registry is supported by the Spanish Group for Research in Contact Dermatitis and Cutaneous Allergy (GEIDAC) and the Spanish Group of Pediatric Dermatology (GEDP)—both working groups of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV). BIOBADATOP is aligned with the TREatment of ATopic eczema (TREAT) Registry Taskforce, an international initiative aimed at harmonizing the collection of observational data of patients on systemic therapy.8,9 The objective of BIOBADATOP is to characterize the safety and efficacy profile of systemic therapies for AD in Spanish hospitals.7,10 A total of 14 dermatology departments currently contribute to this registry. We analyzed all data recorded in the registry from its launch in March 2020–March 2024.

The registry contains information on baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, changes in AD severity, atopic and non-atopic comorbidities, and previous and current treatments. It also records start and discontinuation dates and reasons for discontinuation for all new treatments. Adverse events that occurred since the patient's last visit are reported using the Medical Dictionary for Drug Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) terminology (https://www.meddra.org). Patient data are coded with a unique identifier and entered using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system,11 hosted by AEDV Healthy Skin Foundation.

All adults patients who started an advanced systemic therapy (biologic or JAK inhibitor) during the study period were included. To identify RCT-ineligible patients, we reviewed the eligibility criteria from 74 RCTs included in a recent network analysis of conventional and novel systemic treatments for AD. A total of 58 of these trials specified at least one eligibility criterion.12 We selected the most frequently applied exclusion factors as safety criteria. Trial ineligibility was defined as meeting at least one of the following 8 exclusion factors: advanced age (≥65 years) (applied in 7/58 RCTs); pregnancy, breastfeeding, or desire to become pregnant, (16 RCTs); uncontrolled comorbidities, including hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus (14 RCTs); chronic kidney disease (11 RCTs); present or past history of cancer (11 RCTs); liver disease (10 RCTs); history of tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis B or C infection (9 RCTs); and active or acute infection, including superinfection of AD lesions (7 RCTs).

Statistical analysisDemographic and clinical data are expressed as percentages and absolute values for discrete variables and as mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. The Chi-square or t test was used to compare baseline characteristics and trial eligibility.

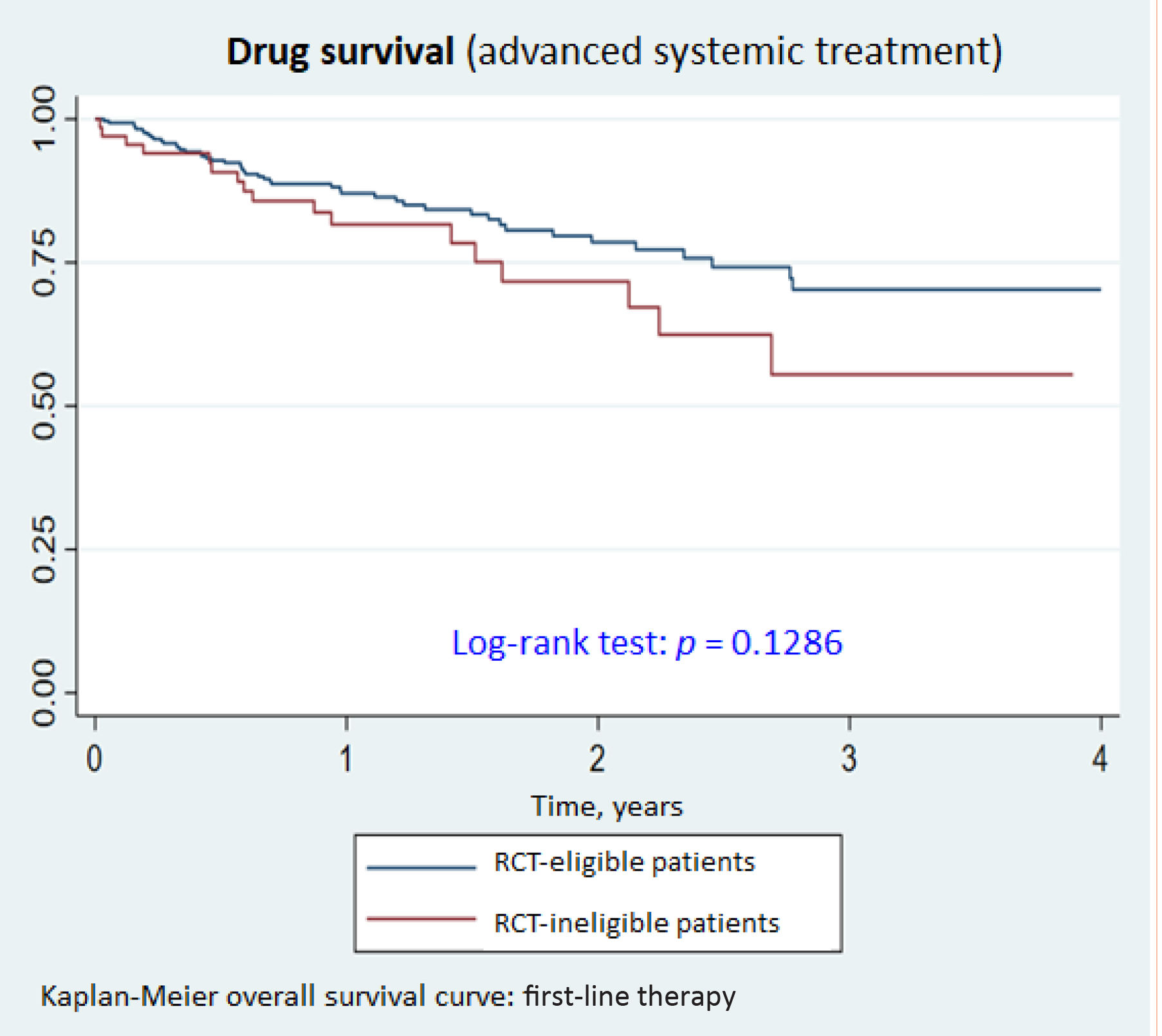

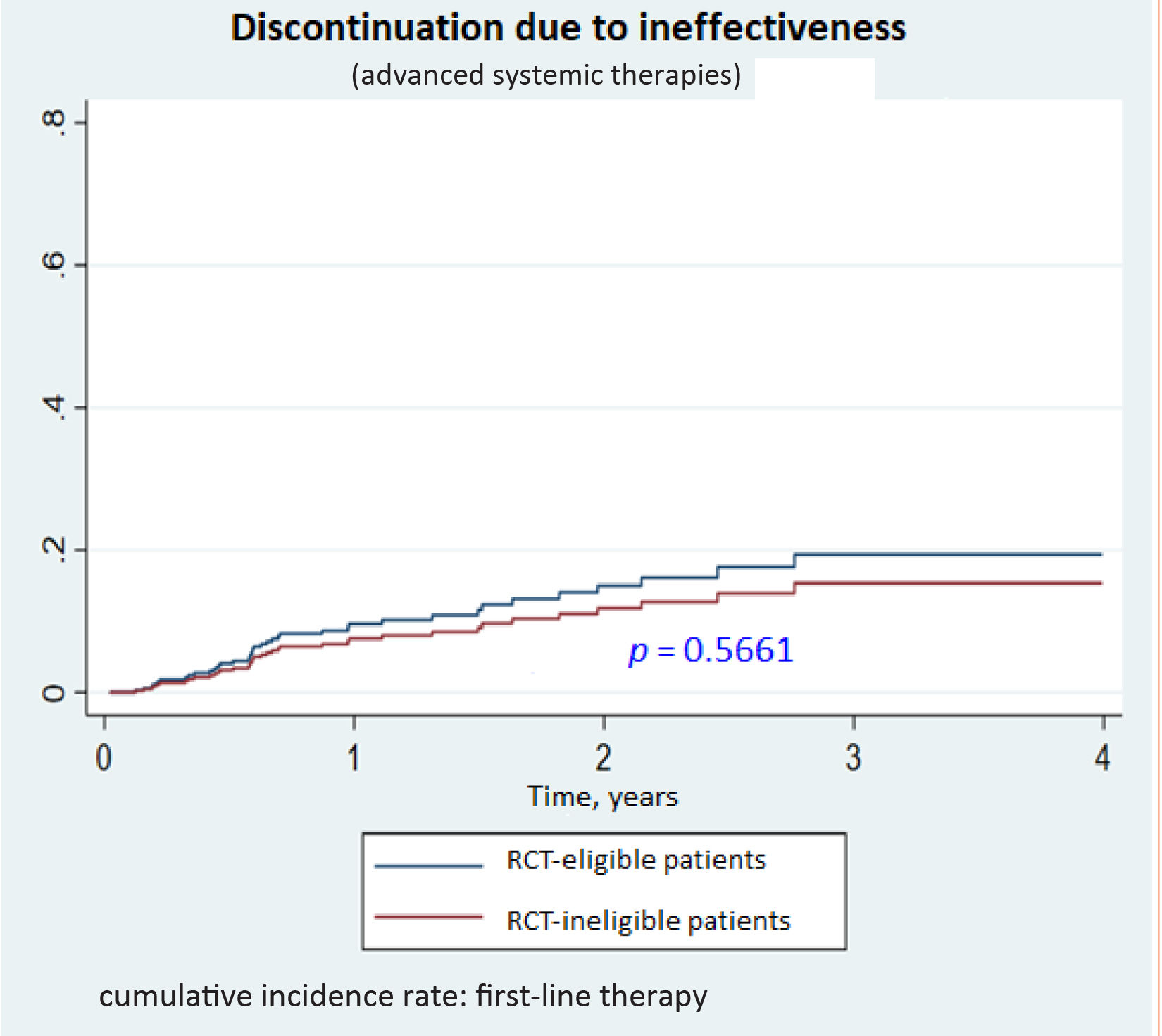

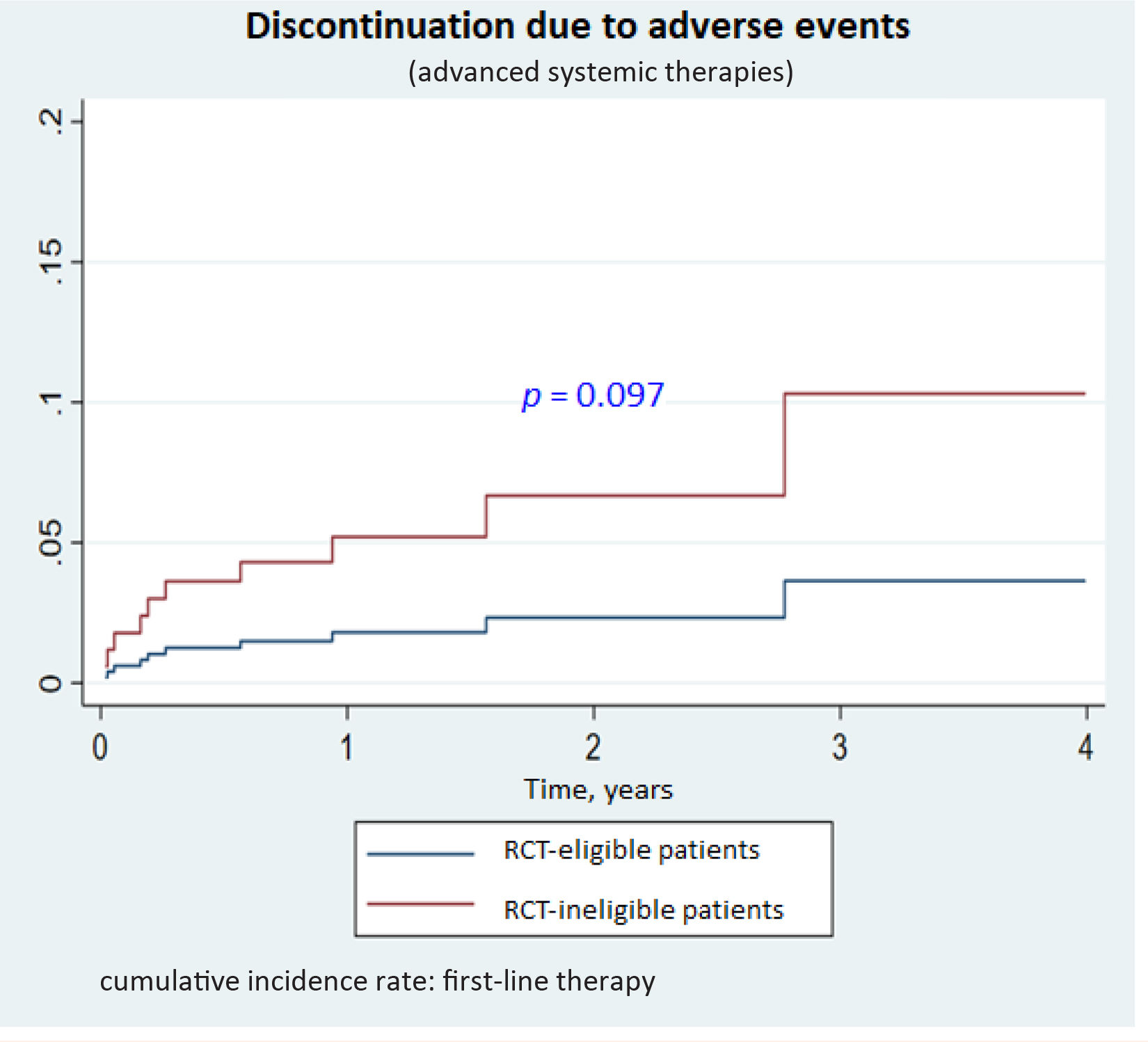

Additional analyses included a comparison of drug survival times between RCT-eligible and -ineligible patients. Drug survival was defined as time from initiation of the first advanced systemic therapy to its completion, interruption, or substitution, or until the completion of the study (March 2024), whichever occurred first. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated and compared using the log-rank test. Reasons for drug discontinuation (treatment ineffectiveness or adverse events) were studied using a competing risks framework. Within this framework, cumulative incidence functions were compared using competing risk regression models, which are interpreted similarly to conventional survival models. Treatment ineffectiveness and adverse events were treated as primary competing risks, while non-clinical reasons for drug discontinuation (e.g., loss to follow-up, patient decision, pregnancy) were treated as censored observations.

The rate of major adverse events by organ system for RCT-eligible and -ineligible patients was calculated per 1000 patient-years of treatment with 95%CIs. To compare the groups, crude and adjusted rate ratios were estimated using a Poisson regression model with robust variance to account for overdispersion.

For the sensitivity analysis, EASI<16 at baseline was included as an additional exclusion criterion. A cutoff value of 16 is frequently used to define disease severity in RCTs.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA v.17.0 software (Stata Corp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

The BIOBADATOP registry was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragón (PA18/051) and fully complies with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and current legislation. The project holds the European Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance (ENCePP) quality seal attesting to scientific independence and transparency. The ENCePP is coordinated by the European Medicines Agency.

ResultsParticipantsA total of 366 adults (201 men [54.9%]) with AD on therapy with a biologic agent (77.6%) or JAK inhibitor (22.4%) were included in this study. The mean (SD) age of patients was 34.6 (18.1) years, and the mean (SD) duration of AD at the time of registry inclusion was 18.4 (15.1) years. Flexural involvement was common, affecting 295 patients (82.9%). A high proportion of patients had lesions in special locations such as the face and eyelids (248, 86.1%), hands (163, 57.4%), and genitals (92, 32.2%).

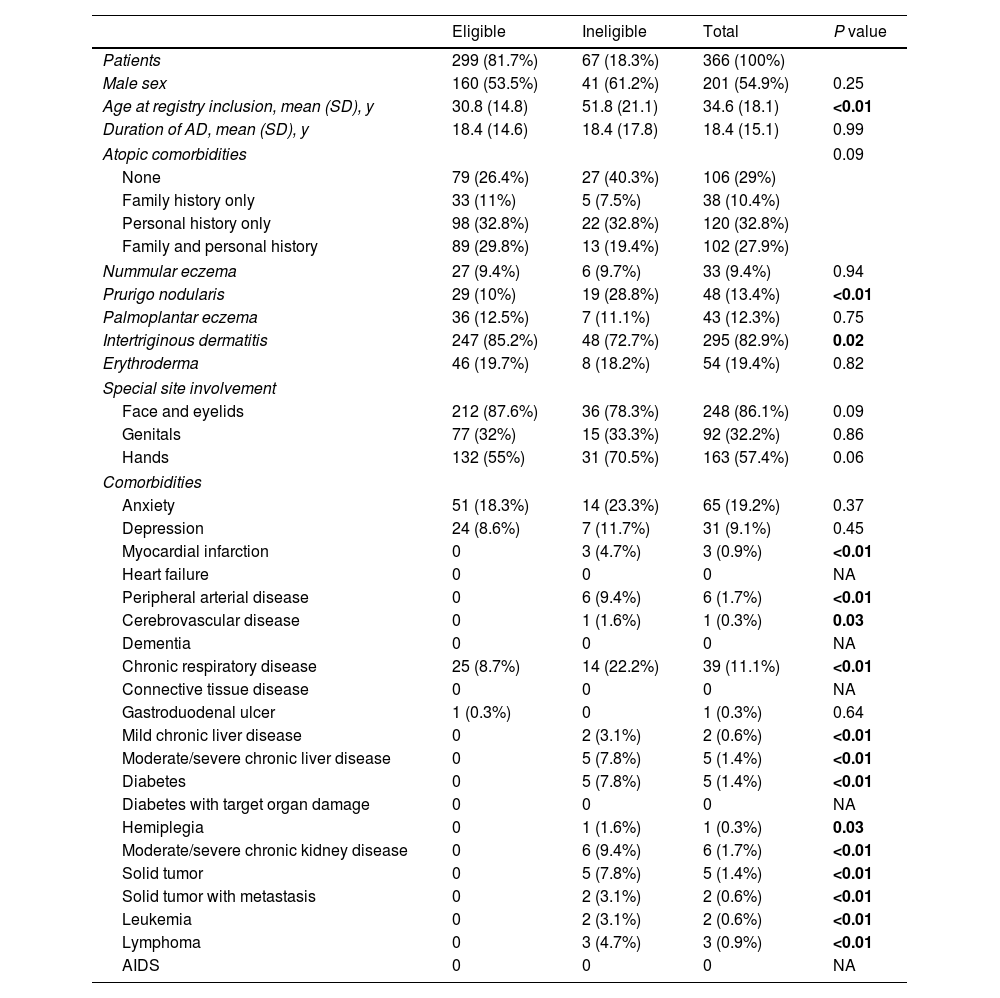

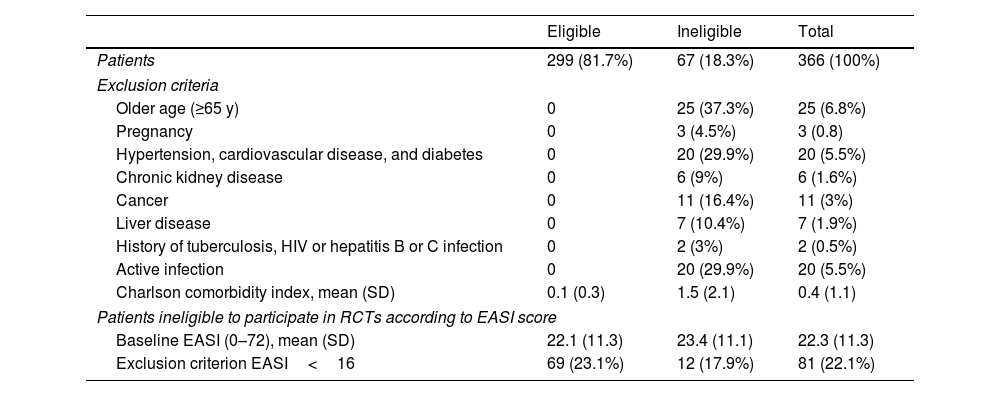

RCT-ineligible patientsSixty-seven (18.3%) of the 366 patients studied would be ineligible to participate in RCTs evaluating the safety and efficacy profile of treatments for moderate-to-severe AD. RCT-ineligible patients were significantly older than eligible patients when included in the registry (51.8 [21.1] vs 30.8 [14.8] years; p<0.01). This is not surprising given the considerable proportion of >65-year patients in this group. Ineligible patients were also more likely to have prurigo nodularis (28.8% vs 10%; p<0.01) and less likely to have flexural dermatitis (72.7% vs 85.2%; p=0.02). No differences were observed for the prevalence of atopic comorbidities between eligible and ineligible patients.

Patients not meeting the eligibility criteria had a higher prevalence of non-atopic comorbidities, including myocardial infarction (4.7%), peripheral arterial disease (9.4%), cerebrovascular disease (1.6%), chronic respiratory disease (22.2%), mild chronic liver disease (3.1%), moderate-to-severe chronic liver disease (7.8%), diabetes mellitus (17.2%), hemiplegia (1.6%), moderate-to-severe chronic kidney failure (9.4%), solid tumors (7.8%), solid tumors with metastasis (3.1%), leukemia (3.1%), and lymphoma (4.7%). These comorbidities, aalong with demographic and clinical characteristics, are shown for both groups in Table 1.

Characteristics of patients from the BIOBADATOP cohort on advanced systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis according to randomized clinical trial eligibility.

| Eligible | Ineligible | Total | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 299 (81.7%) | 67 (18.3%) | 366 (100%) | |

| Male sex | 160 (53.5%) | 41 (61.2%) | 201 (54.9%) | 0.25 |

| Age at registry inclusion, mean (SD), y | 30.8 (14.8) | 51.8 (21.1) | 34.6 (18.1) | <0.01 |

| Duration of AD, mean (SD), y | 18.4 (14.6) | 18.4 (17.8) | 18.4 (15.1) | 0.99 |

| Atopic comorbidities | 0.09 | |||

| None | 79 (26.4%) | 27 (40.3%) | 106 (29%) | |

| Family history only | 33 (11%) | 5 (7.5%) | 38 (10.4%) | |

| Personal history only | 98 (32.8%) | 22 (32.8%) | 120 (32.8%) | |

| Family and personal history | 89 (29.8%) | 13 (19.4%) | 102 (27.9%) | |

| Nummular eczema | 27 (9.4%) | 6 (9.7%) | 33 (9.4%) | 0.94 |

| Prurigo nodularis | 29 (10%) | 19 (28.8%) | 48 (13.4%) | <0.01 |

| Palmoplantar eczema | 36 (12.5%) | 7 (11.1%) | 43 (12.3%) | 0.75 |

| Intertriginous dermatitis | 247 (85.2%) | 48 (72.7%) | 295 (82.9%) | 0.02 |

| Erythroderma | 46 (19.7%) | 8 (18.2%) | 54 (19.4%) | 0.82 |

| Special site involvement | ||||

| Face and eyelids | 212 (87.6%) | 36 (78.3%) | 248 (86.1%) | 0.09 |

| Genitals | 77 (32%) | 15 (33.3%) | 92 (32.2%) | 0.86 |

| Hands | 132 (55%) | 31 (70.5%) | 163 (57.4%) | 0.06 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Anxiety | 51 (18.3%) | 14 (23.3%) | 65 (19.2%) | 0.37 |

| Depression | 24 (8.6%) | 7 (11.7%) | 31 (9.1%) | 0.45 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 3 (4.7%) | 3 (0.9%) | <0.01 |

| Heart failure | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 0 | 6 (9.4%) | 6 (1.7%) | <0.01 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0 | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.03 |

| Dementia | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 25 (8.7%) | 14 (22.2%) | 39 (11.1%) | <0.01 |

| Connective tissue disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Gastroduodenal ulcer | 1 (0.3%) | 0 | 1 (0.3%) | 0.64 |

| Mild chronic liver disease | 0 | 2 (3.1%) | 2 (0.6%) | <0.01 |

| Moderate/severe chronic liver disease | 0 | 5 (7.8%) | 5 (1.4%) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes | 0 | 5 (7.8%) | 5 (1.4%) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes with target organ damage | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Hemiplegia | 0 | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.03 |

| Moderate/severe chronic kidney disease | 0 | 6 (9.4%) | 6 (1.7%) | <0.01 |

| Solid tumor | 0 | 5 (7.8%) | 5 (1.4%) | <0.01 |

| Solid tumor with metastasis | 0 | 2 (3.1%) | 2 (0.6%) | <0.01 |

| Leukemia | 0 | 2 (3.1%) | 2 (0.6%) | <0.01 |

| Lymphoma | 0 | 3 (4.7%) | 3 (0.9%) | <0.01 |

| AIDS | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

The reasons for trial ineligibility are summarized in Table 2. The most common exclusion factors were age≥65 years (37.3%), active infection (29.9%); hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes (29.9%); cancer (16.4%); and liver disease (10.4%). The Charlson comorbidity index was significantly higher in ineligible patients (mean [SD], 1.5 [2.1] vs 0.1 [0.3] for eligible patients) p<0.01).

RCT exclusion criteria applied to define ineligibility.

| Eligible | Ineligible | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 299 (81.7%) | 67 (18.3%) | 366 (100%) |

| Exclusion criteria | |||

| Older age (≥65 y) | 0 | 25 (37.3%) | 25 (6.8%) |

| Pregnancy | 0 | 3 (4.5%) | 3 (0.8) |

| Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes | 0 | 20 (29.9%) | 20 (5.5%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0 | 6 (9%) | 6 (1.6%) |

| Cancer | 0 | 11 (16.4%) | 11 (3%) |

| Liver disease | 0 | 7 (10.4%) | 7 (1.9%) |

| History of tuberculosis, HIV or hepatitis B or C infection | 0 | 2 (3%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Active infection | 0 | 20 (29.9%) | 20 (5.5%) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 0.1 (0.3) | 1.5 (2.1) | 0.4 (1.1) |

| Patients ineligible to participate in RCTs according to EASI score | |||

| Baseline EASI (0–72), mean (SD) | 22.1 (11.3) | 23.4 (11.1) | 22.3 (11.3) |

| Exclusion criterion EASI<16 | 69 (23.1%) | 12 (17.9%) | 81 (22.1%) |

EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

In the sensitivity analysis, the addition of EASI<16 as an exclusion factor increased the proportion of ineligible patients up to 37.2%.

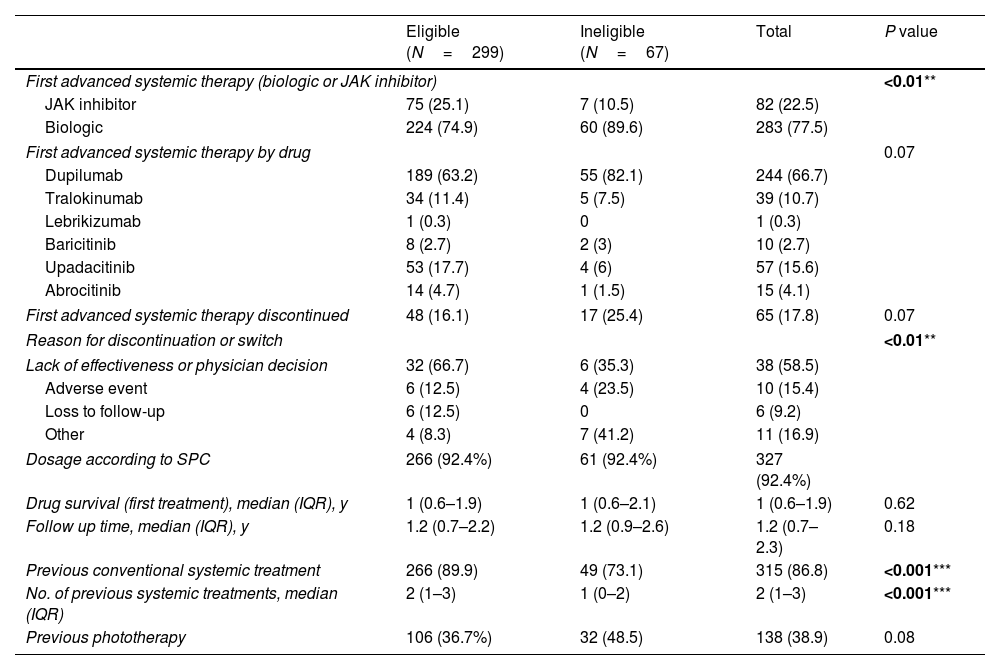

Choice of first advanced systemic therapyThe results showing choice of first advanced systemic therapy for RCT-eligible and -ineligible patients are shown in Table 3.

First advanced treatment according to RCT eligibility (not considering EASI<16).

| Eligible (N=299) | Ineligible (N=67) | Total | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First advanced systemic therapy (biologic or JAK inhibitor) | <0.01** | |||

| JAK inhibitor | 75 (25.1) | 7 (10.5) | 82 (22.5) | |

| Biologic | 224 (74.9) | 60 (89.6) | 283 (77.5) | |

| First advanced systemic therapy by drug | 0.07 | |||

| Dupilumab | 189 (63.2) | 55 (82.1) | 244 (66.7) | |

| Tralokinumab | 34 (11.4) | 5 (7.5) | 39 (10.7) | |

| Lebrikizumab | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | |

| Baricitinib | 8 (2.7) | 2 (3) | 10 (2.7) | |

| Upadacitinib | 53 (17.7) | 4 (6) | 57 (15.6) | |

| Abrocitinib | 14 (4.7) | 1 (1.5) | 15 (4.1) | |

| First advanced systemic therapy discontinued | 48 (16.1) | 17 (25.4) | 65 (17.8) | 0.07 |

| Reason for discontinuation or switch | <0.01** | |||

| Lack of effectiveness or physician decision | 32 (66.7) | 6 (35.3) | 38 (58.5) | |

| Adverse event | 6 (12.5) | 4 (23.5) | 10 (15.4) | |

| Loss to follow-up | 6 (12.5) | 0 | 6 (9.2) | |

| Other | 4 (8.3) | 7 (41.2) | 11 (16.9) | |

| Dosage according to SPC | 266 (92.4%) | 61 (92.4%) | 327 (92.4%) | |

| Drug survival (first treatment), median (IQR), y | 1 (0.6–1.9) | 1 (0.6–2.1) | 1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.62 |

| Follow up time, median (IQR), y | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) | 1.2 (0.9–2.6) | 1.2 (0.7–2.3) | 0.18 |

| Previous conventional systemic treatment | 266 (89.9) | 49 (73.1) | 315 (86.8) | <0.001*** |

| No. of previous systemic treatments, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 1 (0–2) | 2 (1–3) | <0.001*** |

| Previous phototherapy | 106 (36.7%) | 32 (48.5) | 138 (38.9) | 0.08 |

SPC, summary of product characteristics.

* p<.05.

Ineligible patients were less likely to have been previously treated with a conventional systemic drug (73% vs 89.9%; p<0.01). No significant differences were observed for phototherapy.

Ineligible patients were also less likely to have received a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor as first-line therapy (10.4% vs. 25.1%; p<0.01); however, no significant differences were observed when comparing the use of individual agents. Most patients, both eligible and ineligible (92.4%), were treated at the dosages specified in the summaries of product characteristics.

Drug survivalNo significant differences were observed for drug survival between RCT-eligible and -ineligible patients (Figs. 1–3), although the survival curve was consistently higher in eligible patients. The main reasons for treatment discontinuation or switching in eligible vs ineligible patients were inadequate treatment response or physician decision (66.7% vs 35.3%), adverse events (12.5% vs 23.5%), and loss to follow-up (12.5% vs 0%).

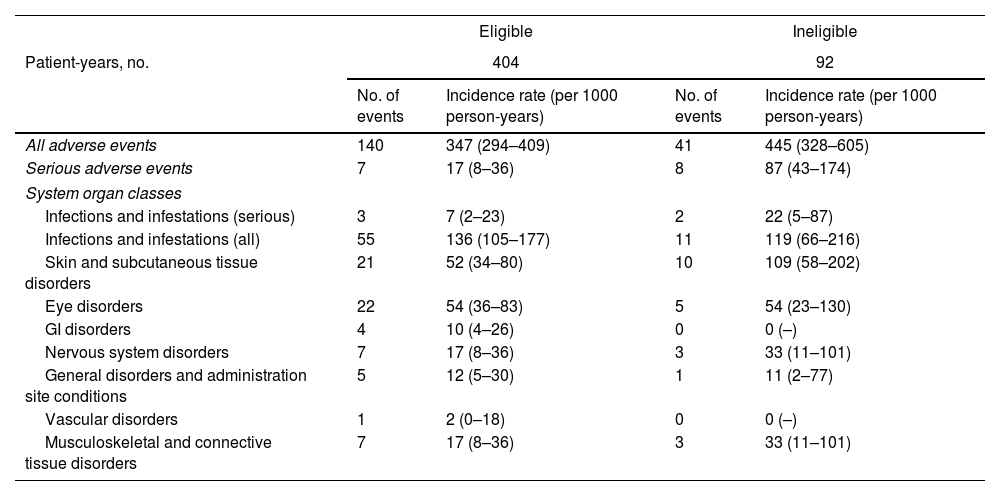

A total of 181 adverse events, including 15 serious ones, were reported for the 366 patients analyzed. The number and rate of events per 1000 person-years are shown by organ system for RCT-eligible and -ineligible patients in Table 4. The most common events were infections and infestations (66 cases), skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (31 cases), and eye disorders (27 cases).

Adverse events in patients with atopic dermatitis deemed eligible and ineligible to participate in randomized clinical trials.

| Eligible | Ineligible | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-years, no. | 404 | 92 | ||

| No. of events | Incidence rate (per 1000 person-years) | No. of events | Incidence rate (per 1000 person-years) | |

| All adverse events | 140 | 347 (294–409) | 41 | 445 (328–605) |

| Serious adverse events | 7 | 17 (8–36) | 8 | 87 (43–174) |

| System organ classes | ||||

| Infections and infestations (serious) | 3 | 7 (2–23) | 2 | 22 (5–87) |

| Infections and infestations (all) | 55 | 136 (105–177) | 11 | 119 (66–216) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 21 | 52 (34–80) | 10 | 109 (58–202) |

| Eye disorders | 22 | 54 (36–83) | 5 | 54 (23–130) |

| GI disorders | 4 | 10 (4–26) | 0 | 0 (–) |

| Nervous system disorders | 7 | 17 (8–36) | 3 | 33 (11–101) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 5 | 12 (5–30) | 1 | 11 (2–77) |

| Vascular disorders | 1 | 2 (0–18) | 0 | 0 (–) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 7 | 17 (8–36) | 3 | 33 (11–101) |

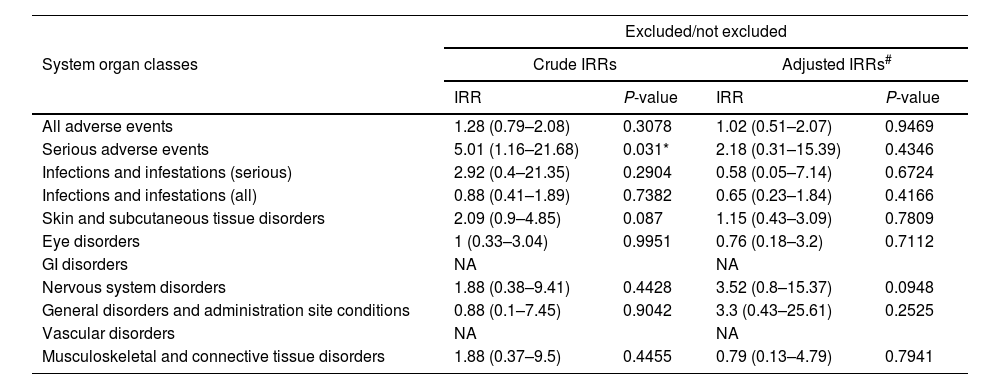

Crude and adjusted incidence rate ratios for the adverse events reported are shown in Table 5. No overall differences were observed between eligible and ineligible patients, but in the univariate analysis, serious events were significantly more common in the ineligible group (rate ratio, 5.01 [1.16–21.68]; p=0.031). The difference, however, lost its significance after adjustment for age, sex, and Charlson comorbidity index in the multivariate analysis.

Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for adverse events.

| Excluded/not excluded | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| System organ classes | Crude IRRs | Adjusted IRRs# | ||

| IRR | P-value | IRR | P-value | |

| All adverse events | 1.28 (0.79–2.08) | 0.3078 | 1.02 (0.51–2.07) | 0.9469 |

| Serious adverse events | 5.01 (1.16–21.68) | 0.031* | 2.18 (0.31–15.39) | 0.4346 |

| Infections and infestations (serious) | 2.92 (0.4–21.35) | 0.2904 | 0.58 (0.05–7.14) | 0.6724 |

| Infections and infestations (all) | 0.88 (0.41–1.89) | 0.7382 | 0.65 (0.23–1.84) | 0.4166 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 2.09 (0.9–4.85) | 0.087 | 1.15 (0.43–3.09) | 0.7809 |

| Eye disorders | 1 (0.33–3.04) | 0.9951 | 0.76 (0.18–3.2) | 0.7112 |

| GI disorders | NA | NA | ||

| Nervous system disorders | 1.88 (0.38–9.41) | 0.4428 | 3.52 (0.8–15.37) | 0.0948 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 0.88 (0.1–7.45) | 0.9042 | 3.3 (0.43–25.61) | 0.2525 |

| Vascular disorders | NA | NA | ||

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 1.88 (0.37–9.5) | 0.4455 | 0.79 (0.13–4.79) | 0.7941 |

Inclusion of an EASI score<16 at the start of treatment in the sensitivity analysis had no significant effect on choice of treatment, drug survival, or adverse event rates.

DiscussionDiscrepancies between clinical trial and real-world patients pose a significant challenge when applying trial findings to routine clinical practice. In this study, we found that 18.3% of patients on advanced systemic therapies for AD in Spain are underrepresented in RCTs. This proportion went up to 22.1% when patients with EASI<16 were included in the analyses (22.1% of the patients treated in real life had EASI<16). While an EASI cutoff value of 16 is widely used to denote severe AD in clinical trials, it is an arbitrary selection criterion. Special site involvement, for instance, is assigned relatively little weight in the EASI tool, meaning that patients with significant facial, hand, or genital lesions may be inaccurately classified as having mild disease, despite having moderate-to-severe symptoms and quality of life impairment.13,14 In other words, this disproportionate weighting can result in an underestimation of disease, potentially excluding patients from participation in clinical trials or access to new treatment if additional assessments are not performed.15,16 Supplementary evaluations are critical for gaining a broader understanding of how AD affects different aspects of the patients’ lives, including work and social functioning. Furthermore, since real-world patients do not typically undergo washout therapy before switching to a new treatment, they may have low baseline EASI scores, even when their treatment is not working.

The proportion of patients deemed eligible or ineligible for a given RCT varies according to the eligibility criteria applied. To identify underrepresented patients in this study, we applied the most common eligibility criteria used by RCTs in an extensive network analysis of AD trials. Most criteria were exclusion criteria related to safety, and, as expected, patients deemed ineligible were significantly more likely to have comorbidities that would exclude them from RCTs evaluating the safety and efficacy profile of advanced systemic therapies for AD.

When comparing the use of individual treatments within our cohort, no significant differences were observed between patients who were eligible or ineligible for RCTs, possibly reflecting clinicians’ confidence in the safety profiles established in those trials. However, when treatments were analyzed by drug class, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors were significantly less likely to be prescribed to patients who did not meet RCT eligibility criteria. This finding is consistent with the European Medicines Agency recommendation to avoid prescribing JAK inhibitors to patients aged>65 years, those with cardiovascular risk, smokers or former smokers, patients with thromboembolic risk, and those with a high risk of cancer, unless no suitable alternatives are available.17 The rationale behind this recommendation is to reduce the risks associated with JAK inhibitors in patients with comorbidities.18,19

Although serious adverse events were significantly more common in RCT-ineligible patients in the univariate analysis, there were no differences after adjusting for age, sex, and Charlson comorbidity index. This suggests that the increased risk of SAEs in ineligible patients has been causally mediated by these variables. Age is a strong predictor of serious adverse events for many drugs and, like comorbid conditions, must be taken into account when taking treatment decisions. Treatments should be chosen only after thoroughly discussing and weighing up the risks and benefits for each patient.18

National and international population-based registries provide important additional information on the safety and efficacy profile of new treatments for AD and other immune-mediated diseases. These registries enable long-term follow-up of a broader, more diverse, patient population, thereby addressing some of the limitations of RCTs, which typically represent a more select population. While RCTs are crucial for evaluating interventions due to their controlled, randomized design, their external validity is often constrained by strict eligibility criteria that do not reflect real-world clinical practice.6,20,21 Additional analyses of registry data can yield more realistic, generalizable insights into treatment outcomes, help identify rare or very rare adverse events and associated risk factors, and be used to evaluate real-world efficacy across diverse patient groups, including patients with special site involvement and those who have switched treatments.

Finally, we observed no differences in drug survival between RCT-eligible and -ineligible patients, suggesting that the exclusion criteria applied in RCTs of novel systemic AD treatments do not significantly affect treatment efficacy or duration.

Our study has some limitations. First, AD research is evolving rapidly, with numerous drugs in the pipeline and clinical trials underway. Most patients in this real-world cohort were treated with dupilumab, the first biologic to be approved for moderate to severe AD in adults. Second, although the use of MedDRA terminology to classify serious adverse events improves the detection of relevant differences and events, it does not distinguish between the mechanisms underlying these events. Finally, the limited statistical power of this study may have prevented us from detecting certain differences or drawing broader conclusions. However, this limitation is intrinsic to studies based on evolving registries such as BIOBADATOP. The value of this registry lies in its ability to deliver real-world evidence that complements insights from controlled clinical trials. As the registry continues to grow, it holds the potential to improve the detection of nuanced differences and provide robust answers to clinically relevant questions that emerge from routine practice.

In conclusion, 18.3% of patients on advanced systemic therapies for AD are misrepresented in clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy profile of these therapies. This represents a significant proportion of real-world patients and highlights the need for more pragmatic clinical trials that address treatment outcomes based on frequent clinical questions. Our findings suggest that future trials should be designed to include older patients, those with atypical disease patterns, and those with severe AD defined by criteria other than absolute EASI scores, such as those with facial, hand, or genital involvement.

FundingThe BIOBADATOP project is managed by the Fundación Piel Sana of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) and receives funding from the pharmaceutical companies Sanofi, AbbVie, Pfizer, and Leo-Pharma. None of these companies had any involvement in study design or conduct; data collection, management, analysis, or interpretation; manuscript preparation, revision, or approval; or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication. The collaborating companies did not participate in the analysis or interpretation of the results.

Conflicts of interestM. Munera-Campos declared to have received fees for consultancy services, presentations, and related activities from AbbVie, Leo-Pharma, Janssen, Sanofi, and Galderma. She has also served as a principal or sub-investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Lilly, Leo-Pharma, Novartis, Janssen, Sanofi, Pfizer, AbbVie, Almirall, UCB, and Galderma.

A. González Quesada declared to have received fees for consultancy services, presentations, and related activities from AbbVie, Leo-Pharma, Sanofi, UCB, and Pfizer. She has also served as a principal or sub-investigator on clinical trials sponsored by Lilly, Leo-Pharma, Novartis, Janssen, Sanofi, Pfizer, AbbVie, Almirall, UCB, and Galderma.

M. Espasandín Arias has led and/or been involved in training activities and attended courses and conferences sponsored by AbbVie, Sanofi, Almirall, Viatris, Pfizer, and Leo-Pharma.

M.A. Lasheras Perez declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

P. de la Cueva Dovao has been involved as a researcher and/or advisor and/or speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, BMS, Boehringer, Celgene, Janssen, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB.

T. Montero-Vilchez declared to have received consultancy and speaker's fees and been involved in clinical trials sponsored by AbbVie, Almirall, Incyte, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Sanofi, Pfizer-Wyeth, and UCB, and Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

R. Ruiz Villaverde declared to have served as an advisor for Sanofi, Janssen, Almirall, and Novartis, given presentations for Almirall, Sanofi, Lilly, AbbVie, Novartis, and Pfizer, and been involved in research projects with Almirall, Sanofi, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Leo-Pharma.

P. Chicharro declared to have provided consultancy services for and been involved in presentations and clinical trials organized by Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Almirall, Sanofi Genzyme, Lilly, AbbVie, Novartis, Leo-Pharma, and Pfizer-Wyeth.

Y. Gilaberte declared to have served as an advisor for Isdin, Roche Posay, and Galderma, given presentations for Almirall, Sanofi, Avene, Rilastil, Lilly, Uriage, Novartis, and Cantabria Labs, and been involved in research projects with Almirall, Sanofi, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Leo-Pharma.

M. Elosua-González declared to have participated as a research and/or speaker for AbbVie, Lilly, Galderma, Leo-Pharma, Pfizer, UCB Pharma, and Sanofi Genzyme.

L. Curto-Barredo declared to have received fees for scientific consulting, presentations, and related activities from AbbVie, Leo Pharma, Sanofi, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Almirall, and Menarini. She has also been involved as a principal or sub-investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Lilly, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi, AbbVie, and Almirall.

J. J. Pereyra Rodríguez declared to have received fees for scientific consulting, presentations, and other activities from AbbVie, Almirall, Galderma, Janssen, Gebro-Pharma, Leo-Pharma, Novartis, Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi, Incyte, UCB, IFC. He has also been involved as a researcher in studies by Novartis, AbbVie, Sanofi, Almirall, Lilly, Galderma, Leo-Pharma, and Argenx.

J.F. Silvestre Salvador declared to have collaborated as a speaker, advisor, and/or researcher for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme.

A. Batalla declared to have participated in training activities and attended courses and conferences sponsored by AbbVie, Celgene, Faes Farma, Isdin, Janssen, Leo-Pharma, Lethipharma, Lilly, Mylan, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi. She has also worked as a sub-investigator in clinical trials sponsored by AbbVie, Celgene, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi and provided consultancy services for AbbVie and Sanofi.

S. Arias-Santiago declared to have been provided consultancy services for and been involved in talks and clinical trials sponsored by AbbVie, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, Sanofi, and Pfizer-Wyeth.

F. J. Navarro Triviño has collaborated in scientific advisory capacities, participated in medical meetings, and contributed to training courses sponsored by Almirall, Sanofi, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, Pfizer, Galderma, Pierre Fabre, Cantabria Labs, La Roche-Posay, Leti Labs, Genové Labs, ISDIN Labs, and Rilastil Labs. He has also worked as a principal investigator or collaborator in clinical trials or research studies for Leo-Pharma and Novartis.

A. Navarro-Bielsa declared to have served as an advisor and/or researcher and/or speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, Janssen, Leo-Pharma, Sanofi, and Galderma.

G. Roustan Gullón declared to have received consultancy and training fees from Sanofi, AbbVie, Lilly, Pfizer, and Leo-Pharma.

M. Bertolín declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

I. Betlloch-Mas declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

I. Castaño declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

C. Couselo-Rodríguez declared to have been involved as a sub-investigator or speaker in projects sponsored by AbbVie, Sanofi, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, UCB, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, and Janssen.

M. Rodríguez-Serna declared to have been involved in advisory roles for Sanofi, Pfizer, Leo, Novartis, and AbbVie.

R. Sanabria de la Torre declared to have been involved in clinical trials for AbbVie, Sanofi, and Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

J. Carlos Ruiz Carrascosa declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

J. Sánchez declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

Á. Rosell Díaz declared to have received speaker's fees from Sanofi and Leo-Pharma and worked as a sub-investigator in studies for Sanofi and Pfizer.

A. M. Gimenez Arnau declared to have served as a medical advisor for Uriach Pharma/Neucor, Genentech, Novartis, FAES, GSK, Sanofi-Regeneron, Amgen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Almirall, Celldex, and Leo-Pharma. She has also been involved as an investigator in projects sponsored by Uriach Pharma, Novartis, and Instituto de Salud Carlos III-ERDF, and has conducted training activities sponsored by Uriach Pharma, Novartis, Genentech, Menarini, Leo-Pharma, GSK, MSD, Almirall, Sanofi, and Avene.

S. Martínez Fernández declared to have conducted training activities and attended courses and conferences sponsored by AbbVie, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, La Roche-Posay, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi. She has also been involved as a sub-investigator in clinical trials sponsored by AbbVie, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Novartis.

I. García-Doval declared to have received travel and training grants for scientific conferences sponsored by AbbVie, MSD, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

M. Á. Descalzo-Gallego declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

J. M. Carrascosa Carrillo declared to have served as a principal investigator/sub-investigator and/or received speaker's fees, and/or served on expert or steering committees for AbbVie, Novartis, Janssen, Lilly, Sandoz, Amgen, Almirall, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Biogen, and UCB.

We thank all the BIOBADATOP researchers for their invaluable work collecting data for the registry during routine clinical practice and all patients and/or their legal representatives for agreeing to participate in the BIOBADATOP registry.