Reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC) is a disease characterized by a collagen epidermal transelimination. The adult-onset acquired form of reactive perforating collagenosis (ARPC) is well documented to be associated with diabetes, likely resulting from chronic hyperglycemia; however, recent reports linking ARPC with autoimmune diseases suggest a multifactorial pathophysiology. We present a case of a 5-year-old presenting ARPC associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM).

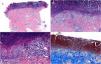

A 5-year-old child without a relevant past medical history presented with a 2-week history of pruritic lesions on his legs along with polydipsia and polyphagia. Skin examination revealed multiple monomorphic, erythematous, circular papules with a central keratotic core, measuring 4–9mm in diameter, diffusely distributed over the lower limbs and trunk (Fig. 1A and B). Laboratory findings showed elevated fasting blood glucose (140mg/dL) and HbA1c (6.4%) together with positive titers of protein tyrosine phosphatase IA2 antibodies. The rest of the study including blood count, biochemistry, autoantibodies and parasitology were normal. A skin biopsy, using both haematoxylin–eosin and Masson's trichrome stain exposed a deep epidermal ulceration with deposition of fibrin-leukocyte material and transelimination of collagen fibres from the base of the ulcer, along with a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory dermal infiltrate with eosinophils (Fig. 2A–D). A diagnosis of T1DM and ARPC was established. A 2-month regimen of a topical corticosteroid, oral cyclosporine at a 3mg/kg/day was initiated along with insulin, achieving clinical remission after 3 weeks and normalization of laboratory tests after 2 months, without recurrences at the 40-month follow-up.

(A–C) H&E stain, 4×/15×/22×. Epidermal hyperplasia, central basophilic plug of keratin, collagen and inflammatory debris. (D) Masson's trichrome stain, 22×. Epidermal ulceration (red) with deposition of fibrin-leukocyte material and transelimination of collagen fibres from the base of the ulcer (blue).

Perforating dermatoses constitute a rare, benign group characterized by transepidermal elimination of connective tissue. First described in 1967 in a 6-year-old girl by Mehregan, RPC is characterized by collagen epidermal transelimination.1 Histologically, epidermal invaginations covered by basophilic collagen that vertically penetrates the dermal papillae are associated with a lymphohistiocytic dermal infiltrate. Clinically, the typical lesions are millimetric, umbilicated, erythematous papules with an ulcerated center covered by keratin, usually located on extensor surfaces of the extremities, trunk, scalp, and buttocks. Lesions often appear following minor trauma and are characterized by localized pruritus and the presence of the Koebner phenomenon.2

Two RPC patterns have been described. The most prevalent one is ARPC, with a mean age of onset around 60 years. ARPC is well-documented to be associated with systemic diseases such as T2DM, chronic kidney disease, neoplasms such as colorectal cancer, and various other conditions.2 On the other hand, familial child-onset RPC (CRPC) is categorized as a genodermatosis with mixed inheritance. The cause is suggested to be a genetic abnormality affecting the collagen in the upper dermis.3 Patients with CRPC typically experience a relapsing-remitting course throughout their lifetimes. Some authors have dismissed the possibility of CRPC being associated with systemic diseases.4

For an extended period, it was widely held that the link between ARPC and DM2 stemmed from prolonged hyperglycaemia, contributing to both altered collagen I/II metabolism and diabetic vasculopathy/nephropathy.5 However, currently, the physiopathology of ARPC is believed to be multifactorial. Multiple reports have associated ARPC with autoimmune diseases such as lupus, dermatomyositis and linear IgA dermatosis, and also described ARPC as a rare adverse effect of panitumumab, sorafenib, erlotinib, among others. This evidence lends support to the hypothesis of an autoinflammatory background. Research by Liu B et al. revealed heightened dermal infiltration of CD3+ T-cells in ARPC, with a prevalence of Th2 cells and the presence of IL-4 and IL-13, mirroring patterns found in atopic dermatitis. Additionally, long-term diabetes is known to induce a pro-inflammatory state. While the molecular pathway remains unclear, the outcome is believed to be a neutrophilic release of proteolytic enzymes following repeated microtrauma, such as scratching. Instances of successful ARPC treatment using immunosuppressants and, more recently, dupilumab may support this hypothesis.6 Given the young age of our patient, long-term hyperglycaemia was ruled-out as a potential cause. A T1DM-mediated immunomodulated trigger could explain the development of ARPC.

In literature, cases of RPC observed in patients younger than 10 years have typically been categorized as CRPC even in the absence of familial history. The only comparable instances involve a 51-year-old man diagnosed concurrently with T2DM and RPC, experiencing lesions since the age of 10, and 2 cases of 8 and 10-year-old children with Down's syndrome diagnosed with RPC, all categorized as ARPC.7,8 Considering the absence of familial history, the lack of relapses post-treatment, and the temporal connection with T1DM, we classify this as a case of child-onset ARPC.

Since there are no comparative clinical trials between treatments, evidence on this regard is anecdotal. Options range from observation, topical retinoids, corticosteroids and phototherapy to systemic immunosuppressants and even dupilumab for refractory or generalized cases. In this case, we selected cyclosporin due to its safety profile and our own successful experience treating atopic dermatitis and a case of elastosis perforans serpinginosa.9

As far as we know, we reported an uncommon case of T1DM-related ARPC in a child, marking the youngest reported case of ARPC to date.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.