Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis whose clinical and topographic distribution requires differential diagnosis, or the possible association with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), requiring patch testing (PT) as part of the diagnostic procedure.

ObjectivesTo describe the epidemiological, clinical, and allergic profile of patients with a primary or secondary diagnosis of psoriasis undergoing PT and compare them with patients with a diagnosis of ACD at the end of the diagnostic process.

MethodsCross-sectional study with data from REIDAC from 2018 through 2023 of selected patients with a diagnosis of psoriasis and/or ACD.

ResultsA total of 11 502 patients were included, 513 of whom had been diagnosed with primary or secondary psoriasis, 3640 with ACD, and 108 with both diseases. Men were more predominant in the groups of patients with psoriasis, psoriasis+ACD, and lesions were more predominantly seen in the hands with little association with atopic factors vs the ACD group. The rate of positivity in PT to the 2022 Spanish battery of allergens was lower in the group with psoriasis only in 27% of the patients. The most common allergens found in the psoriasis group were also the most common ones found in the overall ACD population.

ConclusionsOverall, 36.2% of psoriatic patients tested positive in PT to the 2022 Spanish battery of allergens, which proved that this association is not uncommon. Overall, psoriatic patients had a higher mean age, were more predominantly men, and showed more hand involvement.

La psoriasis es una dermatosis inflamatoria crónica en la que, por clínica y distribución topográfica, a menudo se plantea el diagnóstico diferencial o la asociación con el eccema de contacto alérgico (ECA), circunstancia que lleva a la realización de pruebas epicutáneas (PE).

ObjetivosDescribir el perfil epidemiológico, clínico y alérgico de los pacientes con diagnóstico primario o secundario de psoriasis sometidos a PE, y compararlos con aquellos con diagnóstico de ECA al final del circuito diagnóstico.

MétodosEstudio transversal a partir de los datos del Registro Español de Dermatitis de Contacto (REIDAC), entre 2018-2023, seleccionando los pacientes con diagnóstico de psoriasis y/o ECA.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 11.502 pacientes, de los cuales 513 presentaron el diagnóstico principal o secundario de psoriasis, 3.640 el de ECA y 108 fueron registrados con ambos diagnósticos. Los grupos con psoriasis, y psoriasis y ECA simultáneamente, presentaron una mayor proporción de varones, con lesiones predominantemente en las manos y escasa asociación con comorbilidades atópicas, respecto al grupo con ECA. El porcentaje de positividades en las PE con la batería española 2022 fue menor en los sujetos del grupo únicamente con psoriasis (27% de ellos). Los alérgenos más comunes en los pacientes con psoriasis fueron también los más habituales en la población general con ECA.

ConclusionesEn su conjunto, 36,2% de los pacientes con psoriasis presentó positividades en las PE con la batería española 2022. Aquellos con esta enfermedad mostraron mayor edad media, una proporción mayor de varones y mayor afectación de las manos, respecto al grupo con ECA.

Psoriasis is one of the most common chronic inflammatory dermatoses, with a worldwide prevalence in adults ranging from 0.14% up to 1.92%, being higher in European countries, reaching 1.83% up to 1.92%,1 and Spain, with a prevalence of 2.3%.2

Due to its clinical presentation, topographical distribution, and symptomatology—particularly in the forms of eczematous psoriasis and palmoplantar location—differential diagnosis or association with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is often considered. This circumstance justifies performing patch testing (PT) as a routine procedure of the diagnostic process.3

Describing patients with psoriasis who undergo PT to rule out ACD could improve our understanding of this subject profile and propose optimization strategies regarding diagnosis and management.

The objective of this study is to describe the epidemiological, clinical, and allergic profile of patients diagnosed with psoriasis undergoing PT and compare patients with a primary or secondary diagnosis of psoriasis with those who were not diagnosed with this disease. Specifically, this profile has been analyzed in subjects diagnosed with ACD at the end of the diagnostic process.

Materials and methodsAn analysis was conducted using data from the Spanish Contact Dermatitis Registry (REIDAC), a national multicenter prospective registry of patients undergoing PT that included all patients registered from June 1, 2018 through January 31, 2023.

The REIDAC is a centralized registry developed by the Spanish Working Group of Research in Contact Dermatitis and Cutaneous Allergy (GEIDAC) in conjunction with the Research Unit of Fundación Piel Sana and the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV), which encompasses the main contact dermatitis units in Spain. The REIDAC has successively collected the epidemiological, clinical, and allergic variables of patients undergoing PT in the participant centers.4

The variables collected in this study were sex, age, affected locations, personal history of atopic dermatitis or other atopic comorbidities (asthma, allergic rhinitis), profession, association with occupational factors, duration of symptoms, results of PT with the Spanish 2022 battery (positivity, intensity grade), and primary/secondary diagnosis. ACD was attributed to patients registered as “exclusive ACD,” “predominant ACD,” or “contributing ACD”.

The tests were performed following the recommendations established by the European Society of Contact Dermatitis (ESCD).5 In REIDAC, the ACD study is being conducted using the Spanish standard battery, additional batteries, and patient-specific products based on clinical criteria.6 In this study, only data from the GEIDAC standard battery were considered.

The patients included were categorized into 3 groups: subjects with a primary/secondary diagnosis of psoriasis, those with a diagnosis of ACD, and finally, those who received both diagnoses at the end of the evaluation.

We conducted a descriptive analysis, and the MOAHLFAp index of the groups was compared using the chi-square test. The MOAHLFAp index is an acronym that stands for: M: male, O: occupational dermatitis, A: atopic dermatitis, H: hand, L: leg, F: face, A: age> 40, and p: positivity rate (≥ 1 positive reaction). This index allows for a quick evaluation and comparison of the demographic characteristics of the evaluated population. Stata 17 statistical package (Stata Corp. 2021 Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. Texas, United States) was used for data analysis.

ResultsDuring the study period, patch tests were performed on a total of 11 502 patients, 513 of whom (4.5%) received a primary or secondary diagnosis of psoriasis, 3640 (31.6%) of ACD, while 108 (0.9%) received both diagnoses (psoriasis + ACD) simultaneously. A total of 2972 (70%) were women, 11.7% of whom exhibited psoriasis or psoriasis + ACD, and 1288 (30%) were men, 21.2% of whom exhibited psoriasis or psoriasis + ACD. A total of 2.5% of the patients included shared both diagnoses.

Table 1 shows the epidemiological characteristics of patients with psoriasis and psoriasis + ACD vs the control group (ACD as the sole diagnosis).

Epidemiological characteristics of patients with psoriasis and psoriasis + ACD vs the control group (ACD).

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACD | PSO | PSO + ACD | Total | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Total of patch tests performed (n) | 3640 | 100 | 513 | 100 | 108 | 100 | 4261 | 100 |

| Sex (M) | ||||||||

| Man | 1015 | 28 | 233 | 45 | 40 | 37 | 1288 | 30 |

| Occupational factors (O) | ||||||||

| Yes | 597 | 18 | 14 | 3 | 23 | 22 | 634 | 17 |

| Atopic dermatitis (A) | ||||||||

| Yes | 567 | 16 | 23 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 599 | 14 |

| Location | ||||||||

| Hands (H) | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.196 | 33 | 323 | 63 | 72 | 67 | 1591 | 37 |

| Legs (L) | ||||||||

| Yes | 209 | 6 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 222 | 5 |

| Face (F) | ||||||||

| Yes | 841 | 23 | 27 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 879 | 21 |

| EDAD | ||||||||

| Age > 40 (A) | ||||||||

| Yes | 2425 | 67 | 411 | 80 | 91 | 84 | 2927 | 69 |

| Age (mean, SD) | 47.8 | 17.7 | 51.4 | 14.2 | 50.2 | 12.6 | 48.3 | 17.3 |

| Symptom duration, months (median, Q1-Q3) | 12 | (6-24) | 24 | (12-48) | 12 | (8-36) | 12 | (6-24) |

| COMORBIDITIES | ||||||||

| Asthma | ||||||||

| Yes | 358 | 10 | 36 | 7 | 13 | 12 | 407 | 10 |

| Rhinoconjunctivitis | ||||||||

| Yes | 780 | 22 | 84 | 16 | 21 | 20 | 885 | 21 |

ACD, allergic contact dermatitis; PSO, psoriasis; SD, standard deviation.

Tables 2, 3 and 4 compare the MOAHLFAp indices of the groups with psoriasis and psoriasis + ACD vs those of the ACD group.

Comparison of the MOAHLFAp index between psoriatic patients and patients with ACD.

| ACD (n) % | PSO (n)% | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men (M) | (1.015) 28 | (233) 45 | 2.17 (2.56-1.79) * |

| Occupational factors (O) | (597) 18 | (14) 3 | 0.15 (0.09-0.26%) * |

| Atopic dermatitis (A) | (567) 16 | (23) 5 | 0.25 (0.16-0.39) * |

| Hands (H) | (1.196) 33 | (323) 63 | 3.50 (2.88-4.24) * |

| Legs (L) | (209) 6 | (12) 2 | 0.39 (0.22-0.71) ** |

| Face (F) | (841) 23 | (27) 5 | 0.19 (0.12-0.27) * |

| Age > 40 (A) | (2.425) 67 | (411) 80 | 2.01 (1.60-2.53) * |

| At least 1 positive allergen (p) | (2.959) 81 | (139) 27 | 0.09 (0.07-0.11)** |

ACD, allergic contact dermatitis; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PSO, psoriasis.

Comparison of the MOAHLFAp index between patients with psoriasis + ACD and patients with ACD.

| ACD (n) % | PSO + ACD (n)% | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men (M) | (1.015) 28 | (40) 37 | 1.52 (1.02-2.26) |

| Occupational factors (O) | (597) 18 | (23) 22 | 1.42 (0.89-2.28) |

| Atopic dermatitis (A) | (567) 16 | (9) 8 | 0.50 (0.25-0.99) |

| Hands (H) | (1.196) 33 | (72) 67 | 4.07 (2.71-6.11) * |

| Legs (L) | (209) 6 | (1) 1 | 0.15 (0.02-1.10) |

| Face (F) | (841) 23 | (11) 10 | 0.38 (0.20-0.71)** |

| Age > 40 (A) | (2.425) 67 | (91) 84 | 2.65 (1.57-4.46) * |

| At least 1 positive allergen (p) | (2.959) 81 | (86) 80 | 0.90 (0.56-1.45) |

ACD, allergic contact dermatitis; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PSO, psoriasis.

Comparison of the MOAHLFAp index between psoriatic patients and patients with psoriasis + ACD.

| PSO + ACD (n)% | PSO (n)% | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men (M) | (40) 37 | (233) 45 | 1.41 (0.92-2.17) |

| Occupational factors (O) | (23) 22 | (14) 3 | 0.10 (0.05-0.21)* |

| Atopic dermatitis (A) | (9) 8% | (23) 5% | 0.51 (0.23-1.13) |

| Hands (H) | (72) 67 | (323) 63 | 0.86 (0.55-1.33) |

| Legs (L) | (1) 1 | (12) 2 | 2.57 (0.33-20) |

| Face (F) | (11) 10 | (27) 5 | 0.49 (0.24-1.03) |

| Age > 40 (A) | (91) 84 | (411) 80 | 0.76 (0.43-1.33) |

| At least 1 positive allergen (p) | (86) 80 | (139) 27 | 0.10 (0.06-0.16)* |

ACD, allergic contact dermatitis; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PSO, psoriasis.

Compared to the ACD group, patients from the psoriasis-only group had a higher mean age and longer history of symptoms prior to PT. Additionally, a higher proportion of men vs the control group was reported (45% vs 28% in ACD; P <.001). Regarding the location of lesions, a high percentage of hand involvement was reported in patients with psoriasis (63% vs 33% in ACD; P <.001), as well as less facial involvement (5% vs 23% in ACD; P <.001), fewer atopic comorbidities, and less frequent occupational history as triggers (3% vs 18% in ACD; P <.001).

Overall, the psoriasis + ACD group had very similar baseline characteristics vs patients from the psoriasis-only group, with a higher proportion of men and little atopic context (although both not statistically significant, this trend was indeed observed), a higher proportion of patients older than 40 years (84% vs 67% in ACD; P <.001), and more hand involvement (67% vs 33% in ACD; P <.001) and less facial involvement (10% vs 23% in ACD; P <.01). However, unlike the psoriasis-only group, the psoriasis + ACD group actually showed a higher proportion of occupational factors as triggers (22% vs 3% in psoriasis; P <.001).

The mean time from lesion appearance to assessment was 24 months in patients with psoriasis only and 12 months in patients with ACD and psoriasis + ACD.

The occupational history of patched patients is shown in Table 5. No differences regarding professions were found among the studied groups.

Working history of patch tested patients.

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACD | PSO | PSO + ACD | ACD | |||||

| n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | |

| Total number of patch tested patients (n) | 3.640 | 100 | 513 | 100 | 108 | 100 | 4261 | 100 |

| Main job | ||||||||

| Retiree | 533 | 15 | 70 | 14 | 11 | 10 | 614 | 15 |

| Student | 345 | 10 | 18 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 367 | 9 |

| Housewife | 339 | 10 | 42 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 392 | 9 |

| Administrative staff | 397 | 11 | 67 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 477 | 11 |

| Health care workers | 267 | 8 | 32 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 307 | 7 |

| Other | 1672 | 47 | 269 | 54 | 60 | 56 | 2001 | 48 |

ACD, allergic contact dermatitis; PSO, psoriasis.

The positivity rate of the Spanish 2022 battery in PT was significantly lower in patients with psoriasis only: 27% (139) tested positive for, at least, 1 allergen vs 81% (2959 patients) of the patients from the ACD group (P <.01), and 80% from the psoriasis + ACD group (P <.001). The combined analysis of the psoriasis group plus the psoriasis + ACD group suggests an overall positivity rate of the standard battery of 36.2% in all psoriatic patients who underwent PT (225).

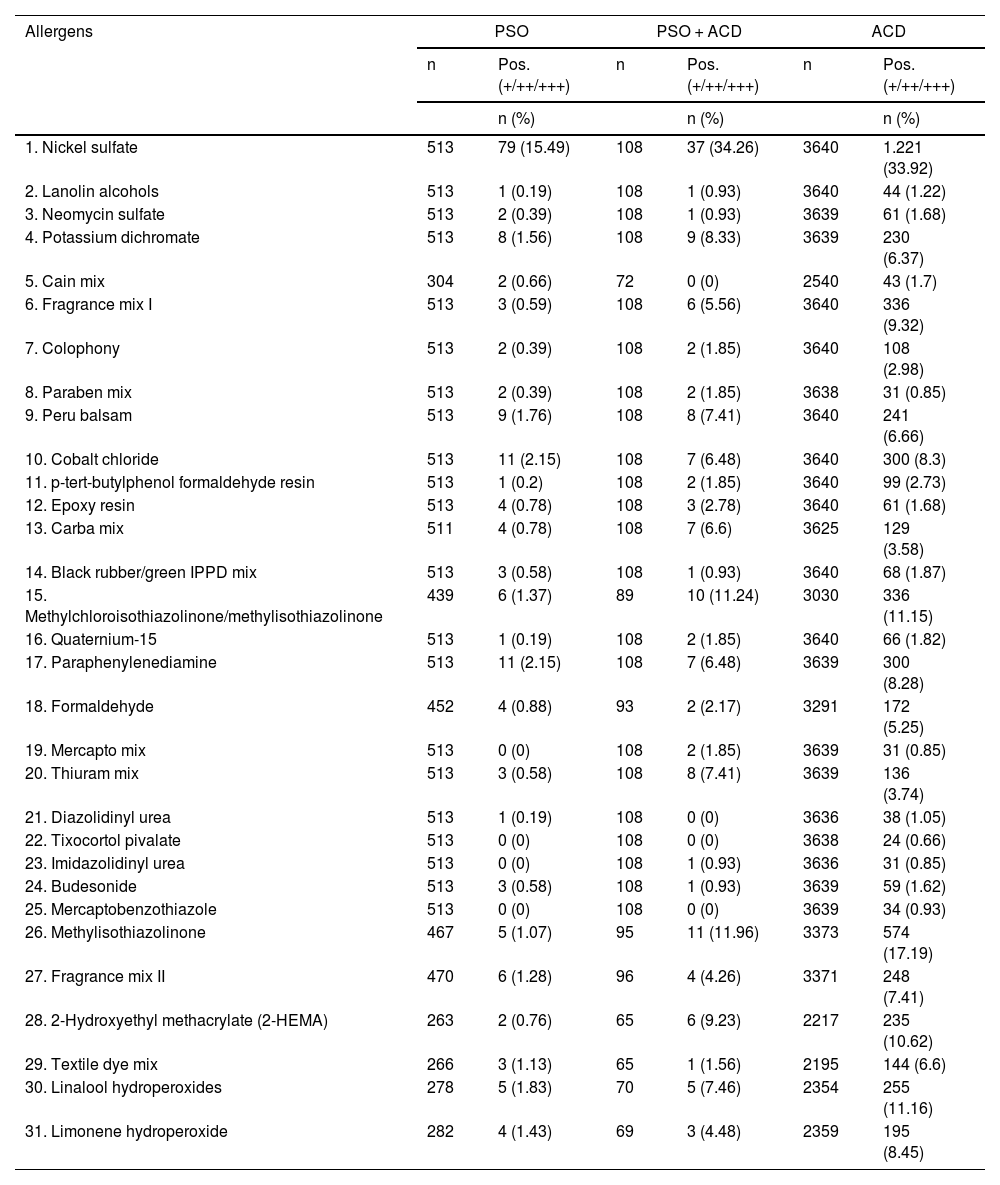

Table 6 shows the complete battery of allergens and their positivities in the 3 groups.

Complete battery of allergens, based on the 2022 GEIDAC standard battery, and their positivities in the psoriasis-only group, the group with ACD, and the group with psoriasis + ACD.

| Allergens | PSO | PSO + ACD | ACD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Pos. (+/++/+++) | n | Pos. (+/++/+++) | n | Pos. (+/++/+++) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| 1. Nickel sulfate | 513 | 79 (15.49) | 108 | 37 (34.26) | 3640 | 1.221 (33.92) |

| 2. Lanolin alcohols | 513 | 1 (0.19) | 108 | 1 (0.93) | 3640 | 44 (1.22) |

| 3. Neomycin sulfate | 513 | 2 (0.39) | 108 | 1 (0.93) | 3639 | 61 (1.68) |

| 4. Potassium dichromate | 513 | 8 (1.56) | 108 | 9 (8.33) | 3639 | 230 (6.37) |

| 5. Cain mix | 304 | 2 (0.66) | 72 | 0 (0) | 2540 | 43 (1.7) |

| 6. Fragrance mix I | 513 | 3 (0.59) | 108 | 6 (5.56) | 3640 | 336 (9.32) |

| 7. Colophony | 513 | 2 (0.39) | 108 | 2 (1.85) | 3640 | 108 (2.98) |

| 8. Paraben mix | 513 | 2 (0.39) | 108 | 2 (1.85) | 3638 | 31 (0.85) |

| 9. Peru balsam | 513 | 9 (1.76) | 108 | 8 (7.41) | 3640 | 241 (6.66) |

| 10. Cobalt chloride | 513 | 11 (2.15) | 108 | 7 (6.48) | 3640 | 300 (8.3) |

| 11. p-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin | 513 | 1 (0.2) | 108 | 2 (1.85) | 3640 | 99 (2.73) |

| 12. Epoxy resin | 513 | 4 (0.78) | 108 | 3 (2.78) | 3640 | 61 (1.68) |

| 13. Carba mix | 511 | 4 (0.78) | 108 | 7 (6.6) | 3625 | 129 (3.58) |

| 14. Black rubber/green IPPD mix | 513 | 3 (0.58) | 108 | 1 (0.93) | 3640 | 68 (1.87) |

| 15. Methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone | 439 | 6 (1.37) | 89 | 10 (11.24) | 3030 | 336 (11.15) |

| 16. Quaternium-15 | 513 | 1 (0.19) | 108 | 2 (1.85) | 3640 | 66 (1.82) |

| 17. Paraphenylenediamine | 513 | 11 (2.15) | 108 | 7 (6.48) | 3639 | 300 (8.28) |

| 18. Formaldehyde | 452 | 4 (0.88) | 93 | 2 (2.17) | 3291 | 172 (5.25) |

| 19. Mercapto mix | 513 | 0 (0) | 108 | 2 (1.85) | 3639 | 31 (0.85) |

| 20. Thiuram mix | 513 | 3 (0.58) | 108 | 8 (7.41) | 3639 | 136 (3.74) |

| 21. Diazolidinyl urea | 513 | 1 (0.19) | 108 | 0 (0) | 3636 | 38 (1.05) |

| 22. Tixocortol pivalate | 513 | 0 (0) | 108 | 0 (0) | 3638 | 24 (0.66) |

| 23. Imidazolidinyl urea | 513 | 0 (0) | 108 | 1 (0.93) | 3636 | 31 (0.85) |

| 24. Budesonide | 513 | 3 (0.58) | 108 | 1 (0.93) | 3639 | 59 (1.62) |

| 25. Mercaptobenzothiazole | 513 | 0 (0) | 108 | 0 (0) | 3639 | 34 (0.93) |

| 26. Methylisothiazolinone | 467 | 5 (1.07) | 95 | 11 (11.96) | 3373 | 574 (17.19) |

| 27. Fragrance mix II | 470 | 6 (1.28) | 96 | 4 (4.26) | 3371 | 248 (7.41) |

| 28. 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2-HEMA) | 263 | 2 (0.76) | 65 | 6 (9.23) | 2217 | 235 (10.62) |

| 29. Textile dye mix | 266 | 3 (1.13) | 65 | 1 (1.56) | 2195 | 144 (6.6) |

| 30. Linalool hydroperoxides | 278 | 5 (1.83) | 70 | 5 (7.46) | 2354 | 255 (11.16) |

| 31. Limonene hydroperoxide | 282 | 4 (1.43) | 69 | 3 (4.48) | 2359 | 195 (8.45) |

ACD, allergic contact dermatitis; GEIDAC, Spanish Working Group of Research in Contact Dermatitis and Cutaneous Allergy; Pos., positivities; PSO, psoriasis.

The standard series allergens detected most frequently in psoriatic patients were nickel sulfate (15.5%), cobalt chloride, and paraphenylenediamine (both 2.2%), linalool hydroperoxides (1.8%), Peru balsam (1.8%), potassium dichromate (1.6%), methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone (1.4%), fragrance mix II (1.28%), and methylisothiazolinone (1.1%).

In the case of patients with psoriasis + ACD, the most frequently detected allergens were nickel sulfate (34.3%), methylisothiazolinone (12%), and methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone (11.2%), 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (9.2%), potassium dichromate (8.3%), linalool hydroperoxides (7.5%), Peru balsam and thiuram mix (both 7.4%), carbamix (6.6%), cobalt chloride, and paraphenylenediamine (both 6.5%).

DiscussionWe present the epidemiological, clinical, and allergic profile of patch-tested patients with psoriasis, comparing them with those with ACD as a control group. The results show that the groups with psoriasis and psoriasis + ACD have a very similar clinical and epidemiological profile, with a higher proportion of men (vs the overall patch-tested patients from the REIDAC) and individuals older than 40 years, with lesions predominantly involving the hands (63% and 67%, respectively), and few associated atopic medical histories. We believe that this may be a specific profile of patients in whom the reason for consultation may lead to the differential diagnosis between hand eczema and palmoplantar psoriasis, and eventually to performing PT as part of the diagnostic process. The results of our study suggest that many of these individuals with palmar involvement will, in fact, be considered psoriatic at the end of the diagnostic process while taking into account that only 2.5% of the patients included in the study received both diagnoses (psoriasis + ACD) simultaneously, and that PT with the standard battery tested negative in 73% of the patients from the psoriasis group vs 19% from the group with a diagnosis of ACD only.

Similarly, in the group with a single diagnosis of psoriasis, the lower relationship of the reason for consultation with professional backgrounds should be highlighted regarding patients with ACD or psoriasis + ACD, despite more hand involvement, a relevant circumstance in the consideration of the disease as occupational or not and with economic implications.

The relationship between psoriasis and ACD has been a matter of discussion, and evidence in the current literature remains limited and heterogeneous.7–14 Overall, psoriasis is not an indication for PT. However, this procedure may be helpful regarding differential diagnosis in some selected groups of patients such as palmoplantar psoriasis, especially in cases of persistent and treatment-resistant lesions, or psoriatic patients treated with biologic drugs who present cutaneous lesions clinically suggestive of contact dermatitis.3,14–16 Nonetheless, we should mention that the association between ACD and psoriasis is possible, regardless of the controversy over whether ACD is actually more or less likely in psoriatic patients.3,9,10,12,17,18

Our data confirm a 27% positivity rate to the Spanish battery in the psoriasis-only group (a 36.2% positivity rate if we consider together the groups with psoriasis plus psoriasis + ACD). These rates are consistent with those from the study conducted by Silverberg et al., where approximately one-third of participants with psoriasis tested positive for, at least, 1 allergen in PT (32.7% vs 57.8% in the remaining patch-tested patients).17

This observation could be related to the fact that, in the group of psoriatic patients, patch tests are performed to rule out the existence of a concomitant or underlying ACD as part of the diagnostic process, even when psoriasis is considered the most likely option in many cases.

Few studies remain available describing the association between psoriasis and ACD, and the characteristics of these patients from large and representative populations of different geographical and occupational settings.

Two studies from the 1990s estimated a prevalence of ACD in patients with vulgar psoriasis between 20% and 27%.7,8 However, subsequent studies showed disparate results.3,9–14 In 2018, a 30-year retrospective observational study described similar rates of ACD between a group of psoriatic patients and the control group.18 More recently, the American Contact Dermatitis Group reviewed its clinical experience from 2001-2016, describing a lower proportion of ACD in patients with a primary or secondary diagnosis of psoriasis vs those without this condition (32.7% vs 57.8%).17 On the other hand, some authors argue that patients with palmoplantar psoriasis may have a higher proportion of ACD vs those with vulgar psoriasis without palmoplantar involvement, suggesting the possible role of contact hypersensitivity as a triggering or aggravating factor in this subgroup, and greater treatment resistance.3,13,15,16. We should mention that this latter subgroup was precisely highlighted in our series.

Few studies analyze the specific allergen profile of psoriatic patients.3,11,12,17–19

In our study, the positivity profile of psoriatic patients only stands out for the positivity to nickel sulfate (15.5% in psoriasis vs 33.9% in ACD) and the lower positivity to preservatives/formaldehyde releasers/perfumes, although we should mention that the number of psoriatic patients in each case is small. However, overall, the most common allergens found were also the most common ones found in the general population with ACD, although positivity to all allergens was less common in psoriatic patients. On the other hand, patients with psoriasis + ACD had a similar positivity profile to those with ACD, both in the type of allergen and its frequency. These findings are consistent with those reported in 3 more recent retrospective studies based on large populations.14,17,18 We should mention that in the present study, only the allergens included in the GEIDAC standard battery were considered.

We should mention that there are certain limitations in this study. The first one being the biased selection of the sample, as only patients whose reason for consultation prompted PT were considered. Secondly, in the psoriasis-only groups, only patients in whom psoriasis was considered the primary or secondary diagnosis in the REIDAC were included, since the recording of psoriasis history is not included as a variable in the latter. On the other hand, there can be an overrepresentation of the psoriatic group with palmoplantar involvement vs other types of psoriasis, given that, in many cases, in this subgroup, patch tests are performed for differential diagnosis with hand eczema. For all these reasons, although our study shows the population studied through PT, the results would not be generalizable to all psoriatic patients.

We should mention that participant centers belong to the National Health System, so many patients from the occupational setting assessed by occupational mutual insurance companies were excluded, which may impact the results regarding occupational exposure. Finally, only the allergens addressed in the GEIDAC standard battery were included. This may explain the rate of negativities reported in the groups with ACD and psoriasis + ACD, which could be due to the fact that these are patients with, at least, 1 positivity for an allergen not included in the standard battery or in this analysis. Although this fact allows for homogeneity among participant centers, it may limit the identification of sensitization to emerging allergens in the study groups.

ConclusionsThe characterization of patch-tested patients from the REIDAC with a diagnosis of psoriasis was presented here. We observed that 2.5% of these patients share both diagnoses—psoriasis + ACD—simultaneously. Of all the subjects diagnosed with psoriasis, 36.2% tested positive for, at least, 1 allergen, which proves that this association is not uncommon. Overall, psoriatic patients are older, predominantly men, and there is greater hand involvement vs the ACD group. The psoriasis-only group also presents less suspicion of occupational involvement and a lower rate of positivities (27%).

The sensitization profile was similar in the psoriatic group vs patients with ACD, with nickel sulfate positivity being the most frequent allergen. The results of this study suggest, as a plausible objective, to determine to what extent contact sensitization found in psoriatic patients could impact the clinical expression of psoriasis per se.

FundingThe REIDAC is a project of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venerology (AEDV) / Fundación Piel Sana. Currently, the REIDAC is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Health through an agreement with the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS). The REIDAC accepts unconditional donations from the pharmaceutical industry. Collaborating companies do not participate, nor have participated in the creation or management of the project. The collection, management, analysis, interpretation, publication, and review of the data generated in the REIDAC are independent of the project's public and private sources of funding. The REIDAC currently receives financial support from Sanofi.

Conflicts of interestA.M. Giménez-Arnau declared conflicts of interest related to consultations, grants, or lectures given on behalf of the following companies: Almirall, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Avene, Celldex, Escient Pharmaceutials, Genentech, GSK, Instituto Carlos III-FEDER, Leo Pharma, Menarini, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi–Regeneron, Servier, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Uriach Pharma/Neucor.

The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.