In-transit metastases have been associated with the presence of various negative prognostic factors in patients with cutaneous melanoma. It has recently been suggested that sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) may lead to an increase in the incidence of this particular type of metastasis. In this study, we analyzed risk factors for the appearance of in-transit metastasis and its potential association with the use of SLNB.

Materials and methodsA prospective study was undertaken in a cohort of 404 patients with cutaneous melanoma seen in the melanoma unit of Hospital San Cecilio in Granada, Spain. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 15.0 and Epidat 3.1 using the χ2 and Fisher exact tests.

ResultsOut of 93 (23%) patients with recurrence at any time, 28 (6.9%) had in-transit metastases. The occurrence of in-transit metastasis was associated with age greater than 50 years, greater Breslow depth and Clark level, the presence of ulceration, positive SLNB, and the presence of other types of recurrence (local recurrence, lymph node metastasis, or distant metastasis). There was no relationship between surgical treatment or performing SLNB and the presence of in-transit metastasis.

ConclusionsThe risk factors for in-transit metastasis are the same as those for any type of recurrence and coincide with factors linked to poor prognosis. Given that in-transit metastases are much more common in patients with positive SLNB, while the technique itself is not linked to their occurrence, these findings suggest that the appearance of in-transit metastasis is linked to biological characteristics of the tumor cells rather than an influence of the surgical technique.

Las metástasis en tránsito en pacientes con melanoma cutáneo son un tipo especial de metástasis que se han asociado a diferentes factores pronósticos adversos. Recientemente se ha sugerido que la técnica de la biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela (BSGC) podría aumentar la incidencia de metástasis en tránsito, por lo que en este trabajo nos proponemos analizar dicha relación y los factores de riesgo de aparición de dichas metástasis.

Material y métodosSe analizó de forma prospectiva una cohorte de 404 pacientes con melanoma cutáneo de la Unidad de Melanoma del Hospital San Cecilio (Granada). Para el análisis estadístico se utilizó el programa estadístico SPSS 15.0 y Epidat 3.1, usando el test Chi-cuadrado y el test exacto de Fisher.

ResultadosDe los 93 (23%) pacientes que presentaron recidiva en algún momento de la evolución, 28 (6,9%) fueron metástasis en tránsito. La aparición de metástasis en tránsito se relacionó de forma positiva con la edad superior a 50 años, mayor espesor de Breslow y nivel de Clark, presencia de ulceración, positividad de la BSGC, y presencia de otro tipo de recidiva (local, ganglionar o a distancia). No hubo relación entre el tratamiento quirúrgico recibido o la realización de la BSGC y la presencia de metástasis en tránsito.

DiscusiónLos factores de riesgo para la aparición de recidivas en general y de metástasis en tránsito en particular son los mismos, y coinciden con otros datos de mal pronóstico. Esto, unido a que las metástasis en tránsito son mucho más frecuentes en el grupo con BSGC positiva y que no se relacionan con la técnica en sí, nos hace pensar que la aparición de este tipo de metástasis se debe a características adversas de la biología tumoral del melanocito, más que a una influencia de la técnica quirúrgica.

The natural history of cutaneous melanoma involves both local spread of the tumor and dissemination to visceral organs through the blood stream or to lymph nodes through the lymphatic vessels. In-transit metastasis is a special type of dissemination that might develop. Defined as the occurrence of single or multiple metastatic deposits between the primary tumor and the boundaries of the tumor's lymphatic nodal basin, in-transit metastasis may be caused by tumor cells that “escape” from lymph vessels draining the tumor toward regional lymph nodes. Such cells then come to rest in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, or even intermediate nodes, growing into highly characteristic metastatic tumors. Some authors have found this type of metastasis to be more common in patients who have undergone selective sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) or complete lymph node dissection,1,2 because the resulting lymphatic stasis encourages the escape of melanoma cells and metastatic spread between the primary tumor and regional lymph nodes.

As SLNB is now included in most protocols for managing cutaneous melanoma, we aimed to analyze risk factors for in-transit metastasis and the relationship between the appearance of this form of dissemination and the use of SLNB.

Materials and MethodsThis prospective study included all patients with cutaneous melanoma seen by the melanoma unit of Hospital San Cecilio de Granada, Spain, from 2003 to 2006; excluded were patients with metastases at the time of diagnosis and with melanoma in situ. The sample comprised 404 patients, all of whom were treated according to the same protocol and for whom the same data were collected. Information recorded included demographic data (name, surnames, sex, and age), clinical variables (date of diagnosis, tumor location, clinical presentation, and treatment), findings of pathology (Breslow depth, Clark level, and presence of ulceration or not, presence of microscopic satellites or not), and clinical course (local recurrence, lymph node involvement, distant metastasis, in-transit metastasis, and follow-up period).

A review of the literature showed that in-transit metastasis has not been defined uniformly across studies. Therefore, we defined types of dissemination for our study in terms of the following concepts:

- -

Local recurrence: reappearance of the tumor in the scar left after removal of the primary tumor

- -

Satellite metastasis: metastasis in the vicinity of the primary tumor but at least 2cm away

- -

In-transit metastasis: a single site of metastasis or multiple sites along the lymphatic pathway draining the primary tumor toward the sentinel lymph node

The data were subject to bivariate descriptive analysis and stratified analysis. SPSS (version 15 for Windows) and EpiDat (version 3.1) were used to compare subgroups in the sample (χ2 test and Fisher exact test). Statistical significance was set at a value of P less than .05.

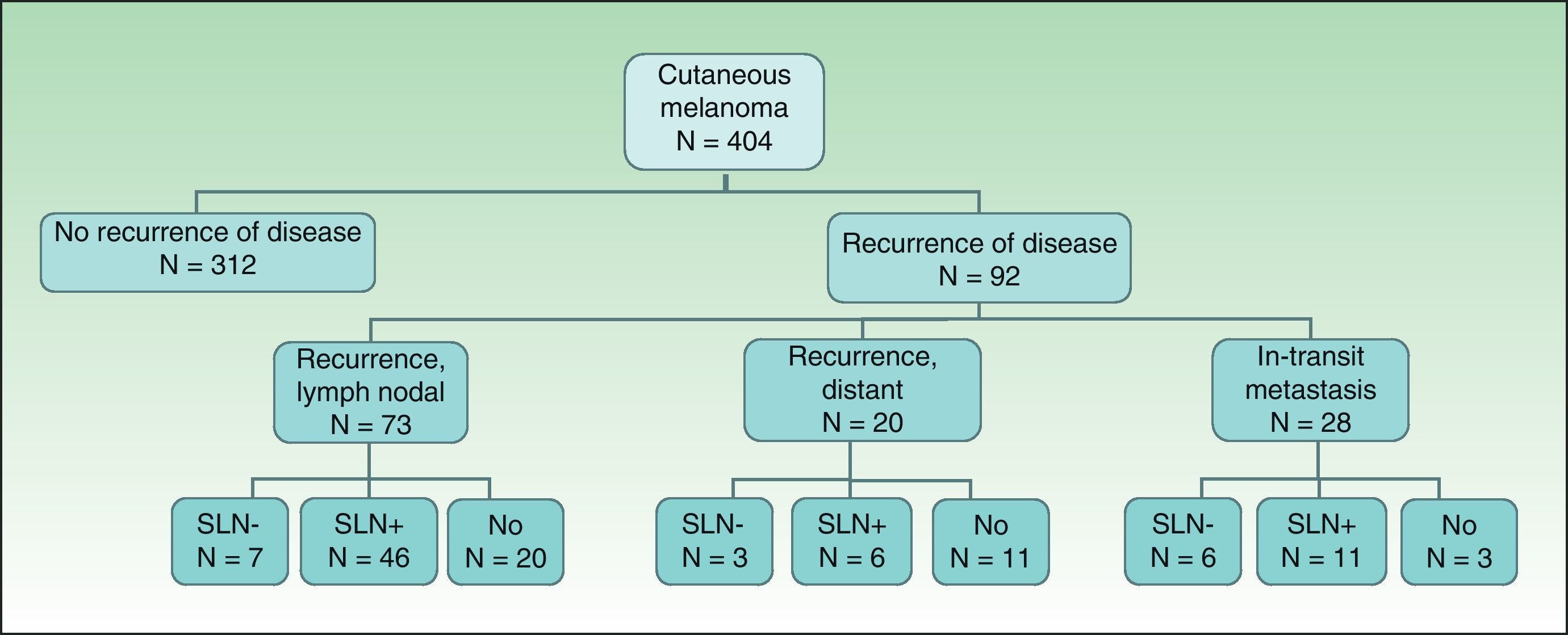

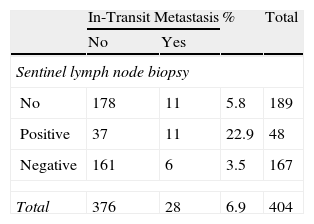

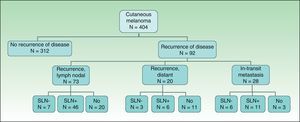

ResultsOf the 404 patients with cutaneous melanoma studied, 93 (23%) had some type of recurrence (mean follow-up period, 18.06 months). Fig. 1 shows the distribution of patients according to clinical course. In-transit metastasis was found in 6.9% of the series, but occurrence was much more common in patients with positive SLNB (22.9%) than in patients with negative findings (3.5%) or in whom SLNB had not been performed (5.8%) (Table 1). The mean in-transit metastasis-free period was 8.93 months. In 70% of recurrences, regional lymph nodes were the first site of dissemination.

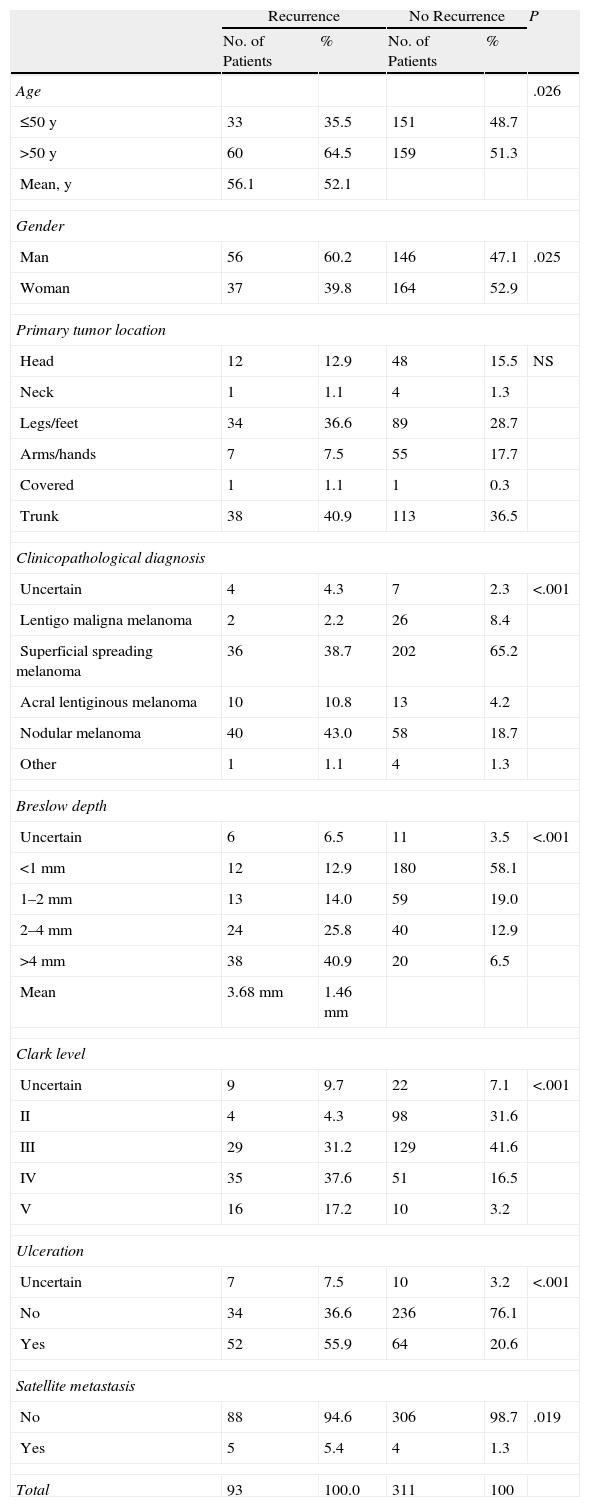

Table 2 shows the characteristics of patients with and without recurrence of disease. In the group of patients with recurrence, mean Breslow depth was greater (3.68mm), Clark levels were higher (levels IV and V were recorded in 54.8% of cases), and more patients had ulceration (present in 55.9%) and nodular melanomas (diagnosed in 43% vs 18.7% of patients with no recurrence). Statistically significant differences were found on comparing the following variables: age (>50 years), male gender, greater Breslow depth and Clark level, ulceration, clinicopathological diagnosis, and presence of satellite metastasis. The only variable that was similar between patients with and without recurrence was the location of the primary tumor.

Characteristics of Patients With and Without Melanoma Recurrence.

| Recurrence | No Recurrence | P | |||

| No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | ||

| Age | .026 | ||||

| ≤50 y | 33 | 35.5 | 151 | 48.7 | |

| >50 y | 60 | 64.5 | 159 | 51.3 | |

| Mean, y | 56.1 | 52.1 | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Man | 56 | 60.2 | 146 | 47.1 | .025 |

| Woman | 37 | 39.8 | 164 | 52.9 | |

| Primary tumor location | |||||

| Head | 12 | 12.9 | 48 | 15.5 | NS |

| Neck | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | 1.3 | |

| Legs/feet | 34 | 36.6 | 89 | 28.7 | |

| Arms/hands | 7 | 7.5 | 55 | 17.7 | |

| Covered | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Trunk | 38 | 40.9 | 113 | 36.5 | |

| Clinicopathological diagnosis | |||||

| Uncertain | 4 | 4.3 | 7 | 2.3 | <.001 |

| Lentigo maligna melanoma | 2 | 2.2 | 26 | 8.4 | |

| Superficial spreading melanoma | 36 | 38.7 | 202 | 65.2 | |

| Acral lentiginous melanoma | 10 | 10.8 | 13 | 4.2 | |

| Nodular melanoma | 40 | 43.0 | 58 | 18.7 | |

| Other | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | 1.3 | |

| Breslow depth | |||||

| Uncertain | 6 | 6.5 | 11 | 3.5 | <.001 |

| <1mm | 12 | 12.9 | 180 | 58.1 | |

| 1–2mm | 13 | 14.0 | 59 | 19.0 | |

| 2–4mm | 24 | 25.8 | 40 | 12.9 | |

| >4mm | 38 | 40.9 | 20 | 6.5 | |

| Mean | 3.68mm | 1.46mm | |||

| Clark level | |||||

| Uncertain | 9 | 9.7 | 22 | 7.1 | <.001 |

| II | 4 | 4.3 | 98 | 31.6 | |

| III | 29 | 31.2 | 129 | 41.6 | |

| IV | 35 | 37.6 | 51 | 16.5 | |

| V | 16 | 17.2 | 10 | 3.2 | |

| Ulceration | |||||

| Uncertain | 7 | 7.5 | 10 | 3.2 | <.001 |

| No | 34 | 36.6 | 236 | 76.1 | |

| Yes | 52 | 55.9 | 64 | 20.6 | |

| Satellite metastasis | |||||

| No | 88 | 94.6 | 306 | 98.7 | .019 |

| Yes | 5 | 5.4 | 4 | 1.3 | |

| Total | 93 | 100.0 | 311 | 100 | |

Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

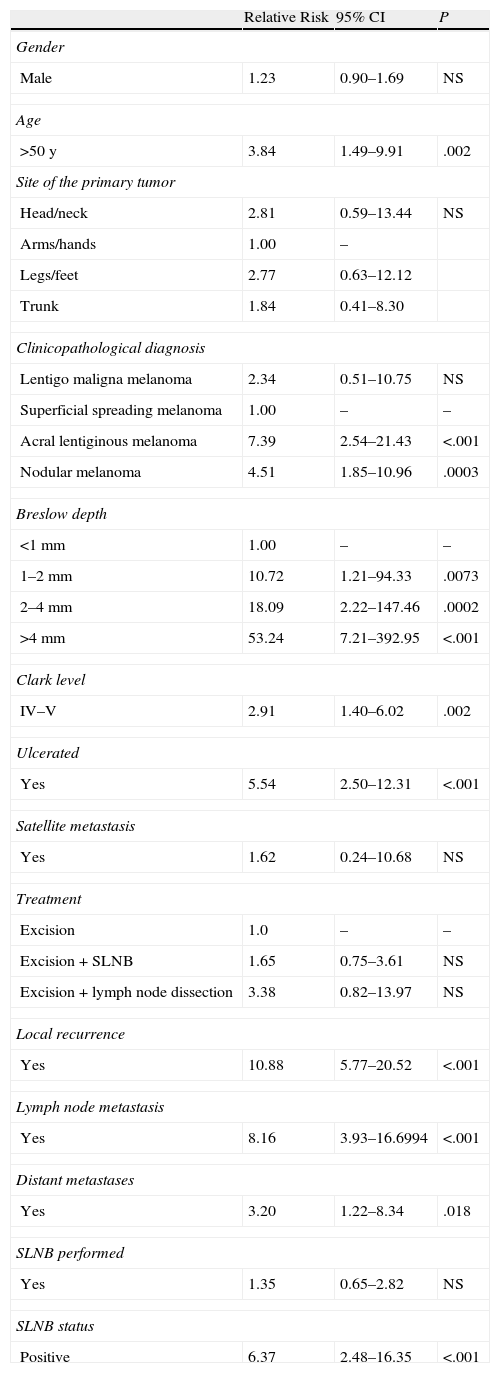

Contingency tables were used to study the relationship between these variables and the development of in-transit metastasis. Significant differences were found in relation to age over 50 years, Breslow depth, Clark level, ulceration, and presence of recurrence (local, lymph nodal, or distant) (Table 3). The relative risk (RR) in relation to Breslow depth increased substantially with tumor thickness: RR was 10.72 for patients with tumors 1 to 2mm thick, 18.09 for those with tumors between 2 and 4mm thick, and 53.24 for melanomas over 4mm thick. Patients with tumors of less than 1mm were used for comparison. Higher Clark level (IV–V) also conferred greater risk (RR, 2.91) in comparison with lower levels, and the presence of ulceration was associated with a RR of 5.54. The presence of in-transit metastasis was also significantly associated with other types of recurrence, whether local, lymph nodal, or distant.

Analysis of Risk Factors for In-Transit Metastasis.

| Relative Risk | 95% CI | P | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.23 | 0.90–1.69 | NS |

| Age | |||

| >50 y | 3.84 | 1.49–9.91 | .002 |

| Site of the primary tumor | |||

| Head/neck | 2.81 | 0.59–13.44 | NS |

| Arms/hands | 1.00 | – | |

| Legs/feet | 2.77 | 0.63–12.12 | |

| Trunk | 1.84 | 0.41–8.30 | |

| Clinicopathological diagnosis | |||

| Lentigo maligna melanoma | 2.34 | 0.51–10.75 | NS |

| Superficial spreading melanoma | 1.00 | – | – |

| Acral lentiginous melanoma | 7.39 | 2.54–21.43 | <.001 |

| Nodular melanoma | 4.51 | 1.85–10.96 | .0003 |

| Breslow depth | |||

| <1mm | 1.00 | – | – |

| 1–2mm | 10.72 | 1.21–94.33 | .0073 |

| 2–4mm | 18.09 | 2.22–147.46 | .0002 |

| >4mm | 53.24 | 7.21–392.95 | <.001 |

| Clark level | |||

| IV–V | 2.91 | 1.40–6.02 | .002 |

| Ulcerated | |||

| Yes | 5.54 | 2.50–12.31 | <.001 |

| Satellite metastasis | |||

| Yes | 1.62 | 0.24–10.68 | NS |

| Treatment | |||

| Excision | 1.0 | – | – |

| Excision+SLNB | 1.65 | 0.75–3.61 | NS |

| Excision+lymph node dissection | 3.38 | 0.82–13.97 | NS |

| Local recurrence | |||

| Yes | 10.88 | 5.77–20.52 | <.001 |

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| Yes | 8.16 | 3.93–16.6994 | <.001 |

| Distant metastases | |||

| Yes | 3.20 | 1.22–8.34 | .018 |

| SLNB performed | |||

| Yes | 1.35 | 0.65–2.82 | NS |

| SLNB status | |||

| Positive | 6.37 | 2.48–16.35 | <.001 |

Abbreviation: NS, not significant; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

We saw no significant differences when we compared the rates of in-transit metastasis between 3 treatment groups: wide excision vs excision+SLNB vs excision+lymph node dissection. Likewise, we found no significant association between the practice of SLNB and the presence of in-transit metastasis in the patient series as a whole (not stratified by biopsy findings). However, positive SLNB was associated with a higher risk of in-transit metastasis (RR, 6.37; 95% CI, 2.48–16.35).

To control for confounding factors, we repeated the analysis taking into consideration age, gender, Breslow depth, Clark level, clinicopathological diagnosis, ulceration, and tumor location. Once again, no significant between-group differences were found except for the subgroups with lentigo maligna melanoma and Clark level I–III classification. When the Fisher exact test was used for comparison, differences were significant only in the group classified in Clark levels I through III.

DiscussionIn-transit metastasis in cutaneous melanoma is associated with a poor prognosis. The prevalence of this subtype of metastasis varies a great deal, ranging from 2.5% to 23% in different patient series.1–6 Such variability is partly explained by the lack of clear definitions for in-transit metastasis, local recurrence, and satellite metastasis; consequently, these types are often pooled as instances of regional/in-transit recurrence. However, if we adhere to a strict definition of in-transit metastasis (deposits at least 2cm from the scar left by tumor excision and lying along the lymphatic drainage pathway), the prevalence rates fall considerably3,4 and are consistent with the occurrence rate of 6.9% in our study. Because local recurrences are often the result of incomplete excision of the primary tumor and are associated with a better prognosis than in-transit metastasis, it makes sense to exclude them from our analysis. We did not analyze survival data in our series, but we did find an association between the presence of in-transit metastasis and the appearance of local, lymph nodal, and distant metastases: this association in itself suggests poor prognosis and would very likely correlate with poor survival. Other studies describe 5-year survival rates ranging from 12% to 54%.3,4

Most in-transit metastases in our patients were found within a year of diagnosis. Others have reported a higher incidence in the first 3 years after diagnosis,4 but even though we followed our patients for a mean of 3 years we saw that most in-transit metastases were detected shortly after diagnosis (mean of just less than 9 months). It might be argued that a longer follow-up period would have brought more cases to light, but as we have noted, the overall incidence in our series was similar to that of other larger ones in which patients were followed longer.

Among studies that have looked for factors influencing the development of in-transit metastasis, one of the largest and most exhaustive ones (1395 patients) found an incidence of in-transit metastasis of 6.6%.3 In that study, Pawlik and coworkers studied patient variables and primary tumor characteristics, finding significant correlations between the occurrence of in-transit metastasis and the following factors: age over 50 years, tumor location on lower extremities, Breslow depth, presence of ulceration, and sentinel lymph node metastasis. They did not directly investigate a relationship to SLNB because all patients in the series had undergone the procedure. However, the authors argued that the fact that in-transit metastasis is associated with positive SLNB supports the theory that tumor biology is more relevant than surgical technique.

The factors that correlated with the development of in-transit metastasis in our study were the presence of ulceration, greater Breslow depth, higher Clark level, a diagnosis of acral lentiginous melanoma or nodular melanoma, advanced age, and positive SLNB. It is interesting that these are almost exactly the same factors that were associated with recurrence of any type in our series; furthermore, the relevance of these factors has already been reported in the literature.3,4,7,8 The only factors that were significantly associated with recurrence in general but not with the appearance of in-transit metastasis in particular were gender and the presence of satellite metastases. The lack of an association between the presence of satellite metastasis and in-transit metastasis is surprising given that these 2 forms share the same regional lymphatic drainage basin; we suppose that the small number of cases of satellite metastasis in our patient series accounts for this observation. Altogether, we think that these results suggest that the factors that have been linked to poor outcomes (low survival, high recurrence rates, etc.) in various studies are indicators of a melanoma biology with intrinsic cell characteristics that predict aggressive tumor behavior.9

Tumor location was not significantly related to the development of in-transit metastasis in our study, in contrast with other series in which melanomas on the lower extremities have been reported to confer greater risk of this type of dissemination.3,7,10,11 The reason for such an association is unclear, although it has been suggested that the more extensive lymphatic system in the legs and perhaps the effect of hydrostatic pressure might contribute to lymphatic stasis and the entrapment of malignant cells. However, our finding of a lack of relationship is consistent with some earlier reports4,7,8 and is therefore unsurprising.The pathogenesis of in-transit metastasis has not yet been clarified. It seems that tumor cells become trapped in lymph vessels as the tumor drains; from the point of entrapment, they would migrate toward the surface, metastasizing to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and on occasion to lymph nodes. Some authors believe that tumor cells are more likely to become trapped when SLNB or lymphadenectomy disrupts lymphatic flow, thereby facilitating in-transit metastasis.1,2,12 Many have questioned the validity of SLNB and would like to see the practice abandoned because of the possible iatrogenic effect and because no benefit in terms of longer survival has been clearly demonstrated in relation to SLNB or (if the biopsy is positive) to more complete lymphadenectomy.13–15

For the moment, attempts to clearly demonstrate a relationship between SLNB and in-transit metastasis have also failed to show conclusive results. Many studies that have attempted to establish causality have suffered from significant bias arising from design flaws. Furthermore, if the theory of lymphatic entrapment of tumor cells were correct, the incidence of in-transit metastasis in patients who have undergone SLNB or complete lymph node resection should be much higher than in those who have only undergone wide local excision of the tumor. In our study no significant association was found between performance of SLNB and in-transit metastasis.

It does seem clear that the incidence of in-transit metastasis rises a great deal when the results of SLNB are positive, possibly reflecting greater melanoma aggressivity as some authors have suggested3,5,9,16 rather than an effect of the surgical technique per se. In fact, in nearly all series the incidences of in-transit metastasis have been very low when SLNB findings are negative; were there a relationship between this technique and in-transit metastasis, the incidence rates would probably be more similar in patients with negative and positive node status. Some authors attribute the higher incidence of in-transit metastasis in patients with positive SLNB to the fact that these patients usually then undergo complete lymph node resection, which would cause greater disruption of lymph drainage and, therefore, increase the likelihood that tumor cells would become trapped, escape, and migrate to the skin. However, a higher incidence of in-transit metastasis has not been seen in studies analyzing patient series in which lymph node resection has been performed; the rates reported in these series were actually very similar to ours17 or only very slightly higher.18

We know that a finding of in-transit metastasis is almost always associated with a poor prognosis and the appearance of nodal or distant metastasis. In fact the factors that were associated with in-transit metastasis in our study and others3,4,7,8 were largely the same as those that predict other types of recurrence and poor overall survival. Therefore, it seems that these factors correspond to melanomas whose cell biology makes them highly prone to distant metastasis. The intrinsically aggressive nature of these tumors would explain why surgical treatment delays the natural history of this disease but does not change it.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Clemente-Ruiz de Almiron A, Serrano-Ortega S. Factores de riesgo de metástasis en tránsito en pacientes con melanoma cutáneo. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:207–213.