Rhinotillexomania is a psychiatric compulsive nose-picking disorder. It is more common in children and young adults, and while it rarely has serious consequences, it can result in serious self-inflicted lesions, such as perforation of the nasal septum and destruction of other facial bone structures.

Case DescriptionA 26-year-old female worker from the health care sector with no history of substance abuse or any other relevant history was evaluated by the dermatology department for nasal septal perforation of 3 years’ duration accompanied by cacosmia, subjective nasal fullness, epistaxis, and frontal-orbital headache associated with instability. She had been seen in the emergency department on multiple occasions, but the physical examination and other tests had always been unremarkable.

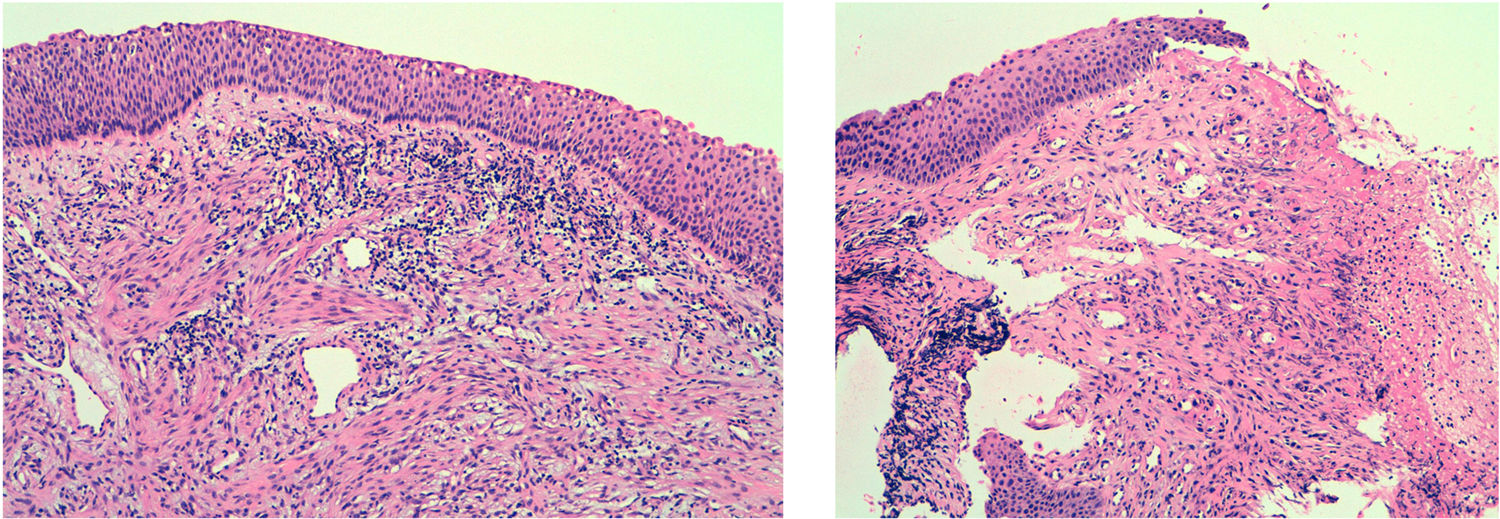

Evaluation by the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) department found no anomalies in any of the following tests: blood tests including serology for syphilis, angiotensin-converting enzyme, antinuclear antibodies, anti-DNA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) with a cytoplasmic distribution, and ANCAs with a perinuclear distribution; urine toxicology; and bacterial cultures (all negative). Rhinoscopy showed septal perforation with invasive borders. Computed tomography showed septal perforation but no signs of disease in the sinuses or other bone structures (Fig. 1). Six punch biopsies were performed and histologic examination showed an ulcerated mucosa with fibrosis and inflammation of the chorion; there was no evidence of vasculitis, thrombosis, granulomas, or atypia (Fig. 2). The patient was prescribed topical and oral antibiotics for 18 months during follow-up at the ENT department but showed little improvement. A septal button was subsequently fitted but was removed 15 days later due to patient intolerance.

At this point, the patient was referred to the dermatology department as in addition to the unresolved septal perforation, she had linear erosions in the right facial and retroauricular region (Fig. 3). Histopathologic examination of the lesion behind the ear showed epidermal erosion but no associated alterations.

Considering the findings and the exhaustive differential diagnosis, we established a diagnosis of exclusion of rhinotillexomania with dermatitis artefacta. The patient was started on oral aripiprazole 2.5mg/d and then 5mg/d. Four months later, the symptoms and facial lesions had disappeared, leaving just the irreparable nasal perforation. At the time of writing, the patient remains asymptomatic.

DiscussionRhinotillexomania, or compulsive nose picking, was first described in 1995, when it was classified as an impulse control disorder and conceptualized as dermatitis artefacta.1 In the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fifth edition), rhinotillexomania is classified under a new category called obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders, which includes body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania, and excoriation disorder (skin picking).2

On rare occasions, rhinotillexomania can lead to complications, such as bacterial infections, serious nose bleeds, septal perforation, and destruction of other facial structures, including the ethmoidal sinuses3,4 and orbit wall.5 Repeated nose picking has also been associated with other obsessive-compulsive behaviors, such as onychotillomania, onychophagia, and neurotic excoriations, among others.6

The etiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder lies in a complex system in which anomalous brain circuitry and chemical alterations have an important role. Links to alterations in the serotonin, glutamate, and dopamine pathways are also being studied.6

Rhinotillexomania is a diagnosis of exclusion that should be established only after ruling out other causes of septal perforation. The most common cause is cocaine use, but other causes include granulomatous disease (Wegener disease, sarcoidosis), infectious disease (Leishmania, leprosy, tuberculosis, syphilis), and malignancy.7 The certainty of the diagnosis is enhanced by a history of psychiatric disease and improvement with treatment.

Antipsychotic drugs are the first-line treatment for dermatitis artefacta. Aripiprazole is classified as an atypical third-generation antipsychotic and it acts as a partial dopamine D2 receptor agonist. It is as safe if not safer than its predecessors and has antidepressant and anti-anxiolytic properties when used at low doses.8

Patients with rhinotillexomania are frequently evaluated by numerous specialists and often seek a second opinion before a diagnosis is established. In addition, most of them undergo multiple examinations and tests before the absence of organic disease is confirmed. In an analysis of the financial impact of dermatitis artefacta in Ireland, Anwar et al.9 calculated a cost of at least €64500 per patient.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Martín-Callizo C, Sacristà M, Fortuño Y, Penín RM, Tribó MJ. Rinotilexomanía. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:370–371.