Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a subtype of scarring (or cicatricial) alopecia that is histologically characterized by the presence of a predominant lymphocytic infiltrate.1 The presence of unexpectedly large numbers of mast cells is a rare finding that has been reported only infrequently in the literature. A recent case described in our unit prompted us to reflect on the pathophysiological role of mast cells in frontal fibrosing alopecia and other varieties of the disorder.

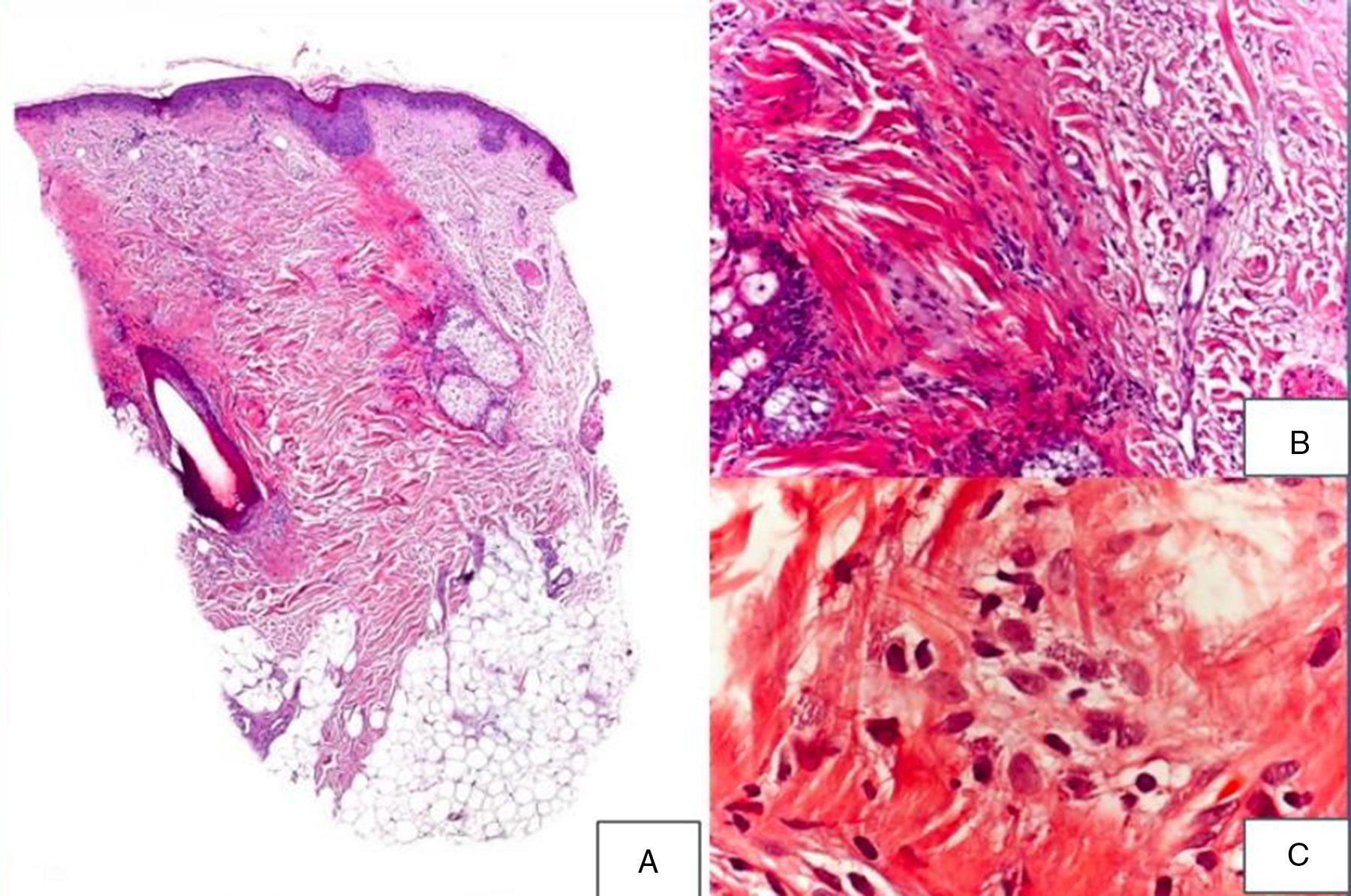

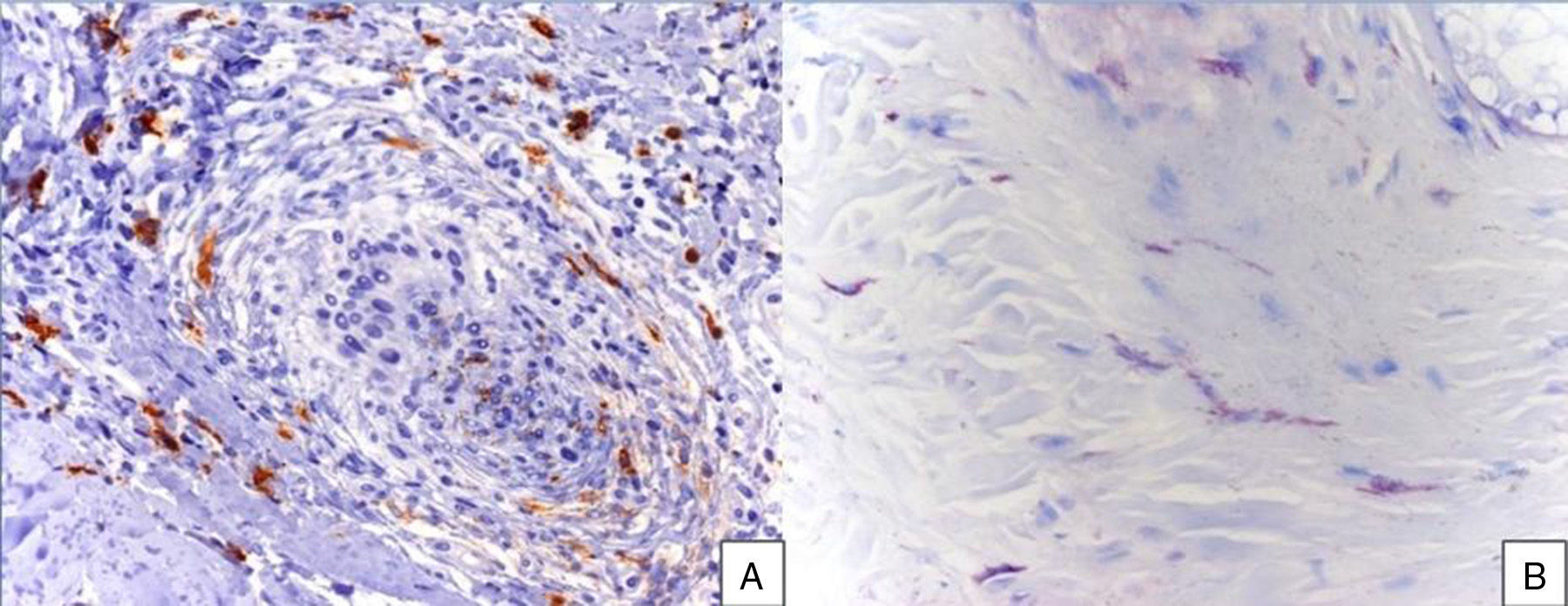

A 48-year-old woman who experienced early menopause at age 42 years consulted for asymptomatic progressive alopecia. She had not undergone any previous treatment. Physical examination revealed recession of the frontal and temporal hairline (Fig. 1, A) with no desquamation, erythema, or perilesional hyperkeratosis (Fig. 1, B). There was no variation in the length or thickness of the hair shaft, nor was there any decrease in hair follicle density in the healthy area. The skin had a parchment-like appearance, and some intact hair follicles were present in the hair-loss band. Alopecia was noted in the distal third of the eyebrows. Clinical suspicion prompted a pathologic examination. Hematoxylin-eosin staining revealed the presence of follicular fibrosis without epidermal involvement (Fig. 2, A). Higher magnification revealed the absence of lymphocytic infiltrate and an increase in the number of mast cells (Fig. 2, B and C). Tryptase staining revealed the presence of mast cells—up to 36 per visual field in some sections—that had even infiltrated the hair follicles (Fig. 3, A). With toluidine blue staining, as many as 12 to 13 mast cells were visible per field (Fig. 3, B). The difference in the number of mast cells per field is explained by the greater sensitivity and specificity of tryptase compared to the metachromatic staining of toluidine blue. The patient was screened for indolent mastocytosis. Tryptase levels were normal (<13.5μg/L), but 24-hour urinary N-methylhistamine was 161μg/L (up to 61.2μg/L being considered normal). In view of these findings, we ordered long-bone radiography, which revealed no alterations, and bone marrow aspiration, which revealed that mast cells accounted for less than 5% of all cells.

A,Presence of fibrosis replacing and destroying the follicle, and absence of epidermal involvement (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 10). B,Difference between follicular fibrosis and normal, interwoven collagen fibers (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 40). C,Absence of lymphocytic infiltrate. Presence of elevated numbers of mast cells (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 200).

Cicatricial alopecia refers to a group of disorders characterized by irreversible hair loss caused by various processes that culminate in the replacement of hair follicles with fibrous tissue. In primary cicatricial alopecias, the hair follicle is the main target of the inflammatory process.2 In 2001, the North American Hair Research Society presented a histopathologic classification of primary cicatricial alopecias according to predominant cell type and clinical characteristics; frontal fibrosing alopecia was among the forms included in the classification.3 The differential histologic finding of an elevated number of mast cells in our patient prompted us to review the literature in order to explain the pathophysiological role of these cells. We found only 1 case with characteristics similar to those of our patient.4 In that case, the preponderance of mast cells was the key to a diagnosis of indolent systemic mastocytosis—an entity that was ruled out in our patient.

Mast cells are found in the skin around blood vessels, smooth muscle cells, hair follicles, and nerve endings.5 They can be identified with hematoxylin-eosin staining, special stains such as Giemsa and toluidine blue, and immunohistochemical techniques (c-kit).6

Mast cells release mediators (histamine, proteases, growth factors, prostaglandins, and cytokines) that are involved in various processes such as scar formation and tissue remodeling, thereby participating in normal wound healing, and they also participate in the pathogenesis of fibrotic diseases such as scleroderma.7,8 They also act as fibroblast growth factor receptors and vascular endothelial growth factor receptors, thereby promoting angiogenesis,8 a process involved in hair follicle development. The role of mast cells in the pathophysiology of scarring alopecia, although still undetermined, could be similar.

What happens in other forms of alopecia? On the basis of histologic evidence of perifollicular fibrosis and an increase in mast cells—which can cause increased elastic fiber synthesis—it has been suggested that there could be a relationship between mast cells and male-pattern androgenetic alopecia.9 Mast cells have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata.10

The reason for elevated histamine metabolite excretion, despite normal tryptase levels and the absence of myeloproliferative disorder, has not been clarified. The amount of methylhistamine produced depends not only on the synthesis and release of histamine but also on the contribution of exogenous histamine from food and beverages and the activity of N-methyltransferase and diamine oxidase enzymes, which decompose histamine into urinary metabolites and can be influenced by alcohol, drugs, and genetic polymorphisms.11 This could explain the high levels of urinary methylhistamine in our patient despite the absence of indolent systemic mastocytosis.

In conclusion, in light of the case described in this letter, we believe that the pathophysiological role of mast cells in the various forms of scarring and nonscarring alopecia needs to be clarified, as it could lead to the identification of new therapeutic targets. Moreover, although we were unable to demonstrate the presence of associated indolent mastocytosis in our patient, we believe that this diagnosis should be considered when the pathologic features described above are encountered.

The authors are grateful for the collaboration of José Aneiros Fernández, a pathologist at Hospital Universitario San Cecilio in Granada, for his large contribution to this case.

Please cite this article as: Almodovar-Real A, Diaz-Martinez MA, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Naranjo-Sintes R. Mastocitos y alopecia cicatricial: ¿hay una clara relación fisiopatológica?. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:854–857.