Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a rare entity first described by Anhalt et al. in 1990.1 It is an autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa, associated with neoplasm, which is generally lymphoid in origin. Because several organs are involved as well as the skin and because the physiopathologic mechanisms associated with the mucosal, skin and internal-organ lesions are not limited to the presence of antibodies specific to adhesion molecules, in 2001, Nguyen et al.2 proposed the term paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome (PAMS).

We describe a patient with PAMS associated with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Case DescriptionA 69-year-old man with a personal history of cerebrovascular accident and type 2 diabetes mellitus visited our department with oral erosions and ulcers that had appeared 6 months earlier.

Physical examination revealed erosive glossitis, cheilitis, pseudomembranous conjunctivitis, and ulcerative keratitis. The patient also presented erythematous scaly lesions on the scalp, maculopapular lesions and reddish-purple plaques on the torso and legs, hyperkeratosis with fissures on the palms and soles, and erosive lesions on the glans and scrotum (Figs. 1 and 2); all these signs appeared 2 months before the patient visited our department.

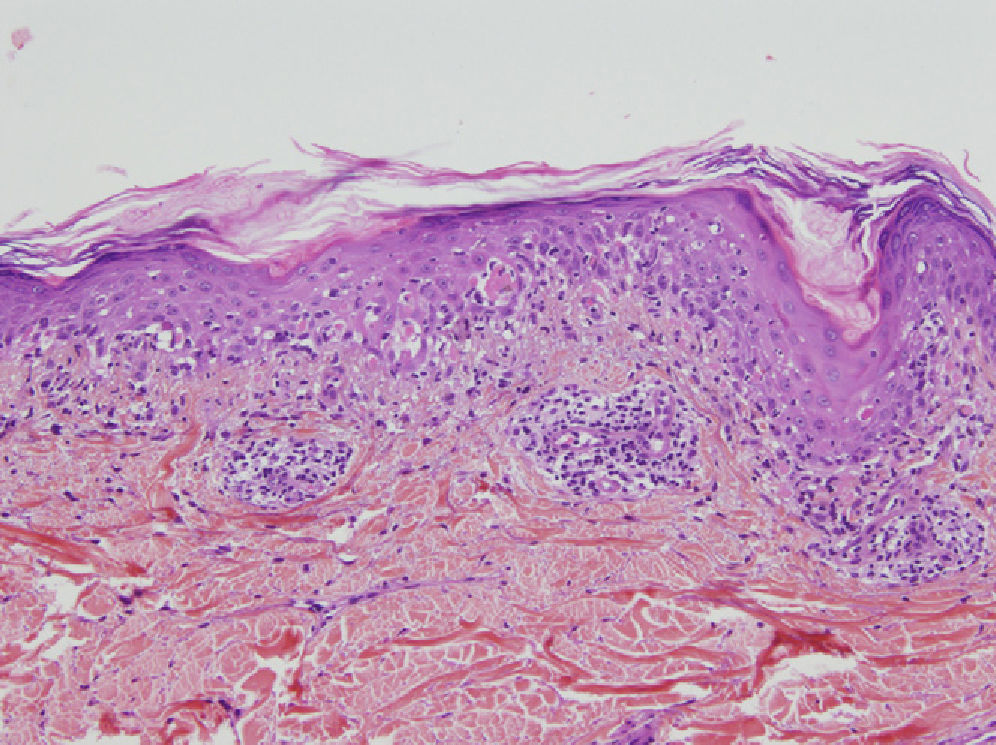

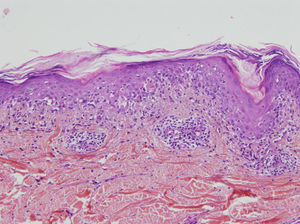

A skin biopsy showed lichenoid interface dermatitis with necrotic keratinocytes (Fig. 3). Direct immunofluorescence showed intercellular deposits of immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgC3 in the epidermis. Indirect immunofluorescence showed intercellular deposits when monkey esophagus was used as a substrate and was negative when rat bladder was used. Immunoblotting identified envoplakin (210kDa) and periplakin (190kDa) antibodies.

A study was performed to search for an occult neoplasm. Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed enlarged mesenteric, mediastinal, and axillary lymph nodes, and a mass in the retroperitoneal soft tissue.

Lymph-node and bone-marrow biopsies were compatible with non-Hodgkin follicular lymphoma and a diagnosis of PAMS associated with non-Hodgkin follicular lymphoma was reached. Treatment of the underlying neoplasm was instated with 8 cycles of chemotherapy using vincristine, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone; 5mg/kg/day of ciclosporin and 1mg/kg/day of methylprednisone were also administered at gradually decreasing doses to treat the cutaneous manifestations. Complete remission of the lymphoma was achieved with no recurrences to date, and the skin lesions resolved completely in 2 weeks. After 3 years of follow-up, the patient presents only mild stomatitis, which is being treated with 100mg/day of ciclosporin.

PAMS is a heterogeneous autoimmune syndrome that involves several internal organs; it is associated with a neoplasm and presents clearly defined clinical, histologic, and immunologic characteristics. The clinical findings of paraneoplastic pemphigus are varied and may resemble pemphigus, lichen planus, erythema multiforme, or graft-versus-host disease. Stomatitis is usually present and often an early sign of the disease—so much so that its absence should call a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus into question. It is characterized by very painful erosive lesions.3,4

Anatomic pathology may show acantholysis but, unlike in common pemphigus, this is less marked and may be accompanied by an intense lichenoid mononuclear infiltrate in the dermal–epidermal junction, with vacuolar degeneration, suprabasal desquamation, and keratinocyte necrosis (lichenoid dermatitis).4

Direct-immunofluorescence findings show intercellular immunoreactants (IgG and complement), as in pemphigus, although IgG and/or complement are also commonly found in the basement membrane; this fact is useful in the differential diagnosis of common pemphigus with paraneoplastic pemphigus or PAMS. It should be remembered that, in some cases, direct immunofluorescence tests may be negative, possibly because of the predominance of lichenoid lesions or the presence of necrotic tissue in the biopsies.5

Serum antibodies against plakins (envoplakin, periplakin, desmoplakin 1 and 2, plectin, and an uncharacterized 170kDa protein) have been detected in all epithelia. However, in a particular subgroup of patients, antidesmoplakin antibodies may be absent and antienvoplakin and antiperiplakin antibodies are therefore considered to be more specific in PAMS.5,6

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a mucocutaneous manifestation of a severe PAMS and precedes diagnosis of the neoplasm in approximately a third of patients. Clinical suspicion of paraneoplastic pemphigus is essential for early diagnosis and treatment of both PAMS and the neoplasm, and thus for preventing fatal complications, such as bronchiolitis obliterans.7,8

Our patient presented with a case of PAMS associated with lymphoma. Diagnosis was made early and, unlike most cases associated with malignant tumors reported in the literature, the outcome was excellent, with the patient alive more than 2 years after diagnosis.

The authors would like to thank Professor J. Manuel Mascaró-Galy, Hospital Clinic Barcelona, Spain, and Josep Herrero, Dermatology Department, Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, Spain, for performing the immunoblotting technique.

Please cite this article as: Hidalgo I, et al. Síndrome multiorgánico autoinmune asociado a linfoma folicular. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:244–246.