In June 2014 a group of dermatologists met in Madrid to reflect on our specialty's role in managing a highly prevalent skin disease: chronic urticaria. The reflections were motivated by the advances in the diagnosis and therapeutic management of this condition that have emerged over the last 5 years. Patients with chronic urticaria develop wheals, angioedema, or both almost daily, and their disease flares are accompanied by specifically cutaneous symptoms such as itching. Renewed interest in this chronic condition, which must always have been a concern for dermatologists, grew out of several scientific and societal events related to urticaria that occurred in 2014. For example, the first ever International Urticaria Day was declared. As a result of this attention, urticaria is now regaining the place it merits on the basis of prevalence, scientific interest, and socioeconomic impact. Guidelines for clinical management have recently been updated,1 and our understanding of the pathogenesis of this disease has advanced. Patient organizations have increased societal demand for greater attention to urticaria, particularly for the approval of safer and more effective therapies. The promise that patients can derive benefits from improved management of a condition that often leads to social isolation gives us, as specialists, an occasion to improve the care of both the skin and the patient. This opinion paper is the outcome of the group's reflections. The aim of the paper is to encourage dermatologists to improve their knowledge of chronic urticaria and its management in routine practice and to consider the possibility of creating a referral center. In the interest of linking national and international discourse on this disease to the dermatologist's experience of it in clinical practice, the paper gives an overview of advances in the diagnosis and management of chronic urticaria.

Urticaria—A Disease of the SkinUrticaria is a disease that involves the skin and mucosal tissues. The usual sign of this condition is the wheal, a primary skin lesion that varies in size and is surrounded by erythema. Known for their evanescence, the lesions last only hours and leave no trace when gone. The patient typically complains of a symptom specific to skin diseases, intense pruritus, which may occasionally be accompanied by a burning sensation or pain. Concomitant angioedema is not unusual. Defined as swelling in the dermis and hypodermis, angioedema lasts some 72hours and also resolves without leaving epidermal or dermal signs. Mucosal tissues are often affected. In fact, in accordance with the most recently agreed upon definition of urticaria from guidelines published after expert consensus, urticaria is a disease characterized by the development of wheals, angioedema, or both.1 This definition therefore embraces clinical presentations of wheals with or without angioedema as well as histamine-mediated angioedema without wheals.

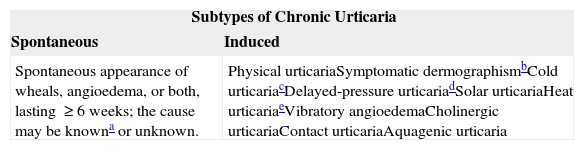

Urticaria is a common skin disease whose lifetime prevalence in populations is estimated at 8% to 20%.2–7 Urticaria is classified according to clinical course as acute, if lasting fewer than 6 weeks, or chronic, if lasting longer. The prevalence of chronic urticaria has been said to range from 0.1% to 0.6% at any particular point5,8 or to average about 0.8% over the course of a year.9 Chronic urticaria—whether spontaneous or induced (Table 1)—is the form that presents diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

Classification in Chronic Urticaria.

| Subtypes of Chronic Urticaria | |

|---|---|

| Spontaneous | Induced |

| Spontaneous appearance of wheals, angioedema, or both, lasting ≥6 weeks; the cause may be knowna or unknown. | Physical urticariaSymptomatic dermographismbCold urticariacDelayed-pressure urticariadSolar urticariaHeat urticariaeVibratory angioedemaCholinergic urticariaContact urticariaAquagenic urticaria |

The daily, or nearly daily, presentation of urticarial signs and symptoms in chronic forms has an enormous effect on patients’ quality of life and work. Certain effects of this disease—sleep disruption caused by itching, facial disfigurement, difficulty with walking or moving ankle or hand joints—can be extremely disabling. The clinical course of chronic spontaneous urticaria can be unpredictable for months or even years; unpredictability can also mark chronic urticaria induced by exposure to such stimuli as friction, cold or sun (Table 1). The co-occurrence of 2 or more types of chronic urticaria (such as spontaneous and delayed-pressure forms) is uncommon.

Little information is available about the duration of chronic urticaria flares. Symptoms last over a year in most patients and a great many suffer for as long as 3 to 5 years; longer periods of up to 10 years have been reported but are exceptional.9 Some patients have been known to have several episodes of chronic urticaria lasting months or years over the course of a lifetime.

Diagnosis and Management of Chronic UrticariaThe patient with chronic urticaria is a frequent user of medical services, whether through primary care clinics or hospital emergency departments and outpatient clinics. The various types of specialist who treat these patients include primary care doctors, internists, allergists, and dermatologists. Often, outcomes are uneven or unsatisfactory, partly due to the variable clinical presentations of this disease but also to lack of understanding of how to manage chronic urticaria properly. As with any disease affecting the skin, mucosal tissues and adnexa, it is essential for dermatologists to be involved. In fact, skin specialists should be the central figures, taking the lead in coordinating the other specialist care that patients with this condition might need.

The first step toward proper management is to arrive at a firm diagnosis of urticaria, ruling out other skin conditions (such as urticarial vasculitis) and systemic processes (such as autoinflammatory syndromes or celiac disease); the type of urticaria must also be established.1 The dermatologist's training and clinical experience afford the background needed for thorough differential diagnosis based on a complete, well-structured clinical history. Whatever the physician's acquired clinical experience with managing these patients, the wheals must be properly examined and their clinical characteristics noted.

Good clinical practice guidelines recommend individualized care of these patients. A tailored approach should take into consideration how long chronic urticaria has been present, the clinical course in previous flares, the characteristics of wheals and their locations, the presence or not of angioedema, severity of symptoms, interference with quality of life, the co-occurrence of different types of urticaria, comorbidity, and response to previous treatments.

The consensus is that therapy should target the rapid and complete resolution of symptoms through application of the most effective and safest treatment.1 Clinical experience with this disease currently holds that treatment should continue for extended periods of time, with adaptations according to changes in symptoms. On the basis of safety and efficacy, first- and second-line therapies include second-generation H1 antihistamines, which are initially prescribed at the recommended dose or continued at up to a maximum of 4-fold the recommended dose. If that approach is ineffective, a third line of treatment consists of adding omalizumab (anti-immunoglobulin E therapy), ciclosporin, or a leukotriene receptor antagonist.1 Adequate control of known and avoidable triggers and exacerbating factors in each patient, as well as an early start of treatment, ensure therapeutic success, favoring better quality of life and quick return to normal work.

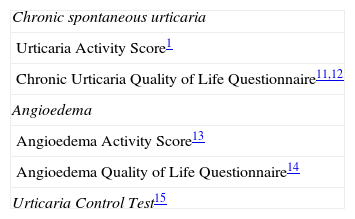

Updating Our Approach to Proper Management of Chronic UrticariaThe roles of dermatologists and dermatology departments in managing chronic urticaria must be revised in the light of advances in our understanding of the physiology and pathogenesis of this disease and the development of new clinical tools (Table 2). There are innovative means to diagnose forms of induced urticaria and a revolution has taken place in therapy with evidence supporting the first monoclonal antibody to be effective in controlling the most serious forms of spontaneous chronic urticaria. The dermatologist's knowledge of management of this disease must be constantly updated. Although the topic is covered in the undergraduate medical school syllabus and in residency training, it is also a recurring theme at national and international dermatology conferences.

Both acute and chronic urticaria, whether spontaneous or induced, are usually diagnosed in outpatient dermatology clinics, on the basis of a structured interview, physical examination, and medical history. Validated instruments for evaluating the current state of disease activity, the impact on quality of life, and the degree of control of urticaria and angioedema (Table 2) are at the disposal of the trained dermatologist.1,10–15 These tools help the physician with both prescribing and monitoring most of the treatments for controlling flares.

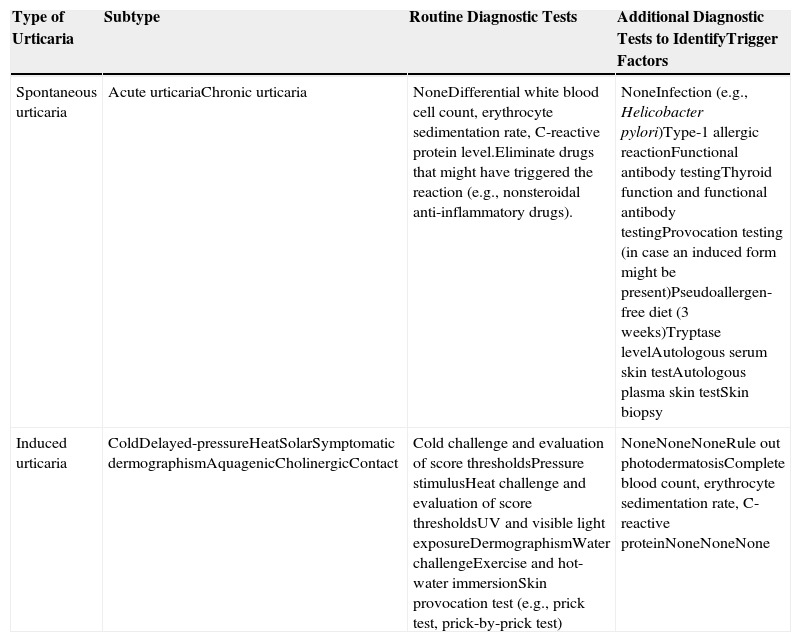

Recent guidelines have recommended a more rational use of complementary tests, by limiting the routine ordering of blood workups, analysis of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein level in managing the disease; avoidance of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is also recommended.1,16 Nevertheless, the patient with this condition asks that we investigate probable causes and triggers and indeed has a right to such investigation. Therefore, for patients with long-term disease or severe symptoms, guidelines recommend further diagnostic work, including evaluating the history of chronic infections; tests for immediate hypersensitivity, functional antibodies, thyroid function, tryptase level, and autoreactivity (autologous serum skin test19; provocation tests for induced forms17,18; and examination of material biopsied from wheals.

The Patient With Chronic Urticaria, the Dermatologist, and the Dermatology DepartmentTraditional subspecializations in dermatology, immunology, and skin allergy reflect the prevalences of urticaria (1% percent of the population) and atopic dermatitis (20% of children and 1% to 3% of adults),20 chronic hand eczema (point prevalence of 4%, 1-year prevalence of 10%, and lifetime prevalence of 15%),10 and the increasing diversity of adverse drug-related skin reactions. The skin is an organ with its own peculiar immunologic functions, and the patient who requires specialized skin care should be fully evaluated by a dermatologist. The dermatology department brings together specialized personnel with tools to study skin problems arising from environmental conditions or immunological processes related to the aforementioned diseases. The protocols and tools used in dermatology referral centers (Table 3) will be needed for the differential diagnosis of induced chronic urticarias.1 Diagnosing these forms properly requires standardized challenge tests, and it can be very useful to apply scoring thresholds when evaluating reactions and establishing severity. Scores are also useful for guiding our choice of therapies and monitoring efficacy.17,18 These methods will be subject to modification as our understanding of the physiology and pathogenesis of urticaria changes, as research agendas shift, and as we assess the implications of treatment for individual patients.

Diagnostic Tests in Chronic Urticaria.

| Type of Urticaria | Subtype | Routine Diagnostic Tests | Additional Diagnostic Tests to IdentifyTrigger Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous urticaria | Acute urticariaChronic urticaria | NoneDifferential white blood cell count,erythrocyte sedimentation rate,C-reactive protein level.Eliminate drugs that might havetriggered the reaction (e.g.,nonsteroidal anti-inflammatorydrugs). | NoneInfection (e.g., Helicobacter pylori)Type-1 allergic reactionFunctional antibody testingThyroid function and functionalantibody testingProvocation testing (in case aninduced form might be present)Pseudoallergen-free diet (3 weeks)Tryptase levelAutologous serum skin testAutologous plasma skin testSkin biopsy |

| Induced urticaria | ColdDelayed-pressureHeatSolarSymptomaticdermographismAquagenicCholinergicContact | Cold challenge and evaluation ofscore thresholdsPressure stimulusHeat challenge and evaluation ofscore thresholdsUV and visible light exposureDermographismWater challengeExercise and hot-water immersionSkin provocation test (e.g., pricktest, prick-by-prick test) | NoneNoneNoneRule out photodermatosisComplete blood count, erythrocytesedimentation rate, C-reactiveproteinNoneNoneNone |

From Zuberbier et al.1

The management of acute or chronic urticaria (whether spontaneous or induced) is supported by the combined experience of dermatology department physicians and by the dermatology literature. Recently published guidelines give therapeutic recommendations according to levels of evidence and the consensus of a wide-ranging and representative sampling of experts.1 The guidelines offer the experienced dermatologist evidence-based information that can be examined critically against the background of clinical practice, and they provide the young dermatologist with a solid scientific basis for embarking on the rational management of this disease. The motivated dermatologist can also find excellent information from international training programs and urticaria schools certified by the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA[2]LEN) or the European Centre for Allergy Research Foundation (ECARF). In Spain, the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) also offers an urticaria training course.

In principle, any motivated dermatologist should be able to manage either spontaneous or induced forms of chronic urticaria. Nevertheless, as with any skin disease, we see variation in severity, associated disability, and resistance to treatment; in addition, there is variability in professional involvement with the condition. As a result, some cases require attention from subspecialists at university hospital referral units. The section of a dermatology department that attends to immunologic diseases and allergic skin conditions should be equipped with the essential tools for thoroughly studying the various types of urticaria. These departments should also have access to the full range of available therapies so that proper differential diagnosis is possible and the patient can then be prescribed the most appropriate treatment. Special treatments, which may include drugs, biologic agents or tolerance induction protocols, have specific infrastructure requirements (for cold or sun exposure, for example).

The Dermatologist and Patient Education, a Key Concern in Chronic UrticariaIn long-term therapy, achieving adequate adherence is important. A critical component of management, therefore, is the physician's responsibility to inform and educate the patient. The dermatologist will need to have a close enough relationship with patients to be able to help them understand the type of disease they have, the prognosis, and the reality of factors that trigger or maintain the process in individual cases. Above all, patients must understand what they can expect from treatment. The treatment plan should be well defined from the start. Early prescription of the most effective and safest treatment is desirable.

Conclusion: The Road Still Before Us in the Management of Chronic UrticariaUrticaria is a common complaint in routine dermatology practice. Any dermatologist should be able to diagnose the type of urticaria, assess disease activity, order any tests necessary for differential diagnosis (e.g., to identify urticarial vasculitis, autoinflammatory syndromes, etc.), and explain a testing protocol and treatment plan to a patient. The dermatologist who specializes in these urticarias in referral units must have the skills to confirm an initial diagnosis, evaluate severity and the impact of an individual's clinical picture, and order the functional tests necessary to establish etiologic factors and intensity case by case. This approach makes it possible to monitor the efficacy and safety of treatments and at the same time to take care to inform and educate the patient appropriately.

The diagnosis and overall management of chronic urticaria is always challenging for both patient and dermatologist. Advances in our understanding of the disease, new tools for monitoring, and the efficacy of biologic agents favor successful outcomes and enhance the patient's sense of well-being. The dermatologist's role is fundamental in this scenario. A skin specialist should coordinate care from other professionals involved in treating patients with urticaria, whether that care is given in settings outside the hospital or in referral units within dermatology departments that combine research on chronic urticaria with clinical care.

To Novartis, for their contribution to the logistics of our working group's meeting.

Jose Carlos Armario Hita, Diego de Argila, Virginia Fernández Redondo, Jesús Gardeazabal, Ana M. Giménez-Arnau, David Moreno Ramirez, Javier Ortiz de Frutos, Esther Serra-Baldrich, Juan Francisco Silvestre, Manel Velasco, J. Jaime Vilar Alejo

Hospital Universitario de Puerto Real, Cádiz

Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Madrid

Complejo Hospitalario Universitario, Santiago de Compostela

Hospital de Cruces, Bilbao

Hospital del Mar, Institut Mar d’Investigacio Médiques, Universitat Autònoma, Barcelona

Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Sevilla

Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid

Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona

Hospital General Universitario de Alicante, Alicante

Hospital Arnau de Vilanova, Valencia

Hospital Universitario Dr. Negrín, Gran Canaria

See Appendix A for further information on members of the Urticaria Opinion Group

Please cite this article as: Giménez-Arnau AM, Vilar Alejo J, Moreno Ramirez D, en nombre de Grupo de Opinión de Urticaria. Manejo diagnóstico y terapéutico de la urticaria crónica por el dermatólogo y papel del servicio de dermatología. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:528–532.