Dermatology in-house call is uncommon in the Spanish national health system. The objective of the present study was to define the groups of dermatologic diseases and conditions most frequently seen in the emergency department and to evaluate the need for dermatology in-house call in the training of medical residents.

Material and methodsWe performed a descriptive study of all patients who attended the emergency department with a skin complaint during a 1-year period (June 2013 to May 2014) and were assessed by 9 dermatology residents. The study variables were date/day, sex, age, diagnosis, special surgical procedures, additional laboratory tests, and need for hospitalization and/or follow-up. We also evaluated patients attending their first scheduled visit to the dermatologist between January and June 2014 in order to compare the most frequent conditions in both groups.

ResultsA total of 3084 patients attended the emergency room with a skin complaint (5.6% of all visits to the emergency department), and 152 different diagnoses were made. The most frequent groups of diseases were infectious diseases (23%) and eczema (15.1%). The specific conditions seen were acute urticaria (7.6%), contact dermatitis (6.1%), and drug-induced reactions (4.6%). By contrast, the most frequent conditions seen in the 1288 patients who attended a scheduled dermatology appointment were seborrheic keratosis (11.9%), melanocytic nevus (11.5%), and actinic keratosis (8%). A follow-up visit was required in 42% of patients seen in the emergency department. Fourth-year residents generated the lowest number of follow-up visits.

ConclusionsWe found that infectious diseases and eczema accounted for almost 40% of all emergency dermatology visits. Our results seem to indicate that the system of in-house call for dermatology residents is very useful for the hospital system and an essential component of the dermatology resident's training program.

La existencia de guardias de Dermatología es escasa en nuestro sistema nacional de salud. El objetivo del presente estudio es definir cuáles son los grupos de enfermedades y afecciones dermatológicas más frecuentes que acuden a urgencias y valorar la necesidad de dichas guardias para la formación del médico interno residente (MIR).

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo de los pacientes que acudieron a urgencias de Dermatología durante el periodo de un año (junio de 2013-mayo de 2014), que fueron evaluados por 9MIR de la especialidad. Las variables a estudio fueron: fecha/día, sexo, edad, diagnóstico, procedimientos quirúrgicos especiales, pruebas complementarias de laboratorio, si requirieron o no hospitalización o revisión. Además, se evaluaron los pacientes nuevos que acudieron a una consulta programada de Dermatología entre los meses de enero y junio del 2014, con el objetivo de comparar las afecciones más frecuentes en ambos grupos.

ResultadosUn total de 3.084 pacientes fueron atendidos en urgencias dermatológicas, que representó el 5,6% de las urgencias vistas en el hospital. Se realizaron 152 diagnósticos diferentes. Los grupos de enfermedades más frecuentes fueron: infecciosas (23%) y eccemas (15,1%). Los diagnósticos individuales fueron: urticaria aguda (7,6%), eccema de contacto (6,1%) y toxicodermias (4,6%). Ello contrasta con los diagnósticos más frecuentes en los 1.288 pacientes estudiados pertenecientes a la consulta programada (queratosis seborreica [11,9%], nevus melanocítico [11,5%] y queratosis actínica [8%]). Un 42% de los pacientes vistos en urgencias requirió revisión; los MIR de 4.° año fueron los que menor número de revisiones generaron.

ConclusionesEn nuestro estudio el grupo de dolencias infecciosas y eccemas representan cerca del 40% del total de las consultas urgentes. Nuestros resultados parecen indicar que la realización de guardias de Dermatología por parte de los MIR de esta especialidad es de gran utilidad para el sistema hospitalario y que son necesarias en la formación integral del especialista en Dermatología.

The usefulness of treating dermatologic conditions in the emergency department has been the subject of debate since the service first started. Dermatology in-house call is uncommon in the Spanish National Health system: very few health care centers in Spain provide 24-hour in-house call, because, at least in part, most dermatologic emergencies are neither serious nor life-threatening.

The World Health Organization understands an emergency as a case in which the lack of medical attention could lead to the patient's death in a matter of minutes and in which first aid is of vital importance, regardless of who administers it. Similarly, the World Health Organization defines an emergency as the fortuitous appearance in any place or during any activity of a problem with diverse causes and varying severity that generates awareness of an imminent need for attention by the subject experiencing the emergency or his/her family. If we apply this definition in our daily clinical practice, the appearance of various types of skin lesions, many of which are associated with symptoms, generates in the patient or his/her family the awareness of an immediate need for medical attention and, in some cases, considerable alarm. Consequently, dermatologic conditions are a common presenting complaint in the emergency department.1 Dermatologic conditions have been calculated to account for up to 8%-10% of hospital admissions in Spain,1–4 thus illustrating how difficult it can be for the general public to distinguish between the concept of an emergency visit and life-threatening severity. In addition, demand for care in the general emergency department is increasing.5 In Spain, the presence of these services has led to an exponential increase in the demand for health care, from approximately 18 million emergencies in 1977 to 26.2 million emergencies in 2008.5 On occasion, this increase has led to saturation and collapse.

Moreover, section 6.4 of the Training Program of the Specialty of Medical-Surgical Dermatology and Venereology (Official State Gazette dated September 25, 2007; Order SCO/2754/2007) considers in-house call an essential component of a physician's training program in the internal medicine service or surgical service during rotation and in the dermatology department during the remainder of the training period.

Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain is a tertiary institution with 24-hour dermatology in-house call that has been training medical residents for the last 15 years. We decided to evaluate the emergencies managed in our department over a 1-year period by analyzing the different types of dermatologic conditions requiring emergency treatment. We also aimed to evaluate the role of dermatology in-house call in the training of medical residents. Therefore, on the one hand, we compared the emergency condition with one managed at a scheduled visit with a dermatologist and, on the other, we recorded the percentage of checkups and direct discharges by the resident depending on the year of residency training.

Material and MethodsWe performed a descriptive, prospective study of the clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients seen in our emergency department over a 12-month period (June 1, 2013 to May 31, 2014). Our hospital provides specialized care to a population of approximately 230 000 inhabitants in the metropolitan area of Salamanca, Spain.

Patients were evaluated by 9 dermatology residents (second, third, and fourth years). Each resident is supervised by a staff physician. Supervision is either direct on working days (8 am to 3 pm) or deferred to the following day or 48hours later (patients seen during the weekend) in cases of diagnostic doubt.

The study variables were as follows: date/day the patient was seen, sex, age, diagnosis, special surgical procedures (biopsy, suture of wounds and excisions), additional laboratory tests (analysis, serology, culture), need for hospitalization, and need for a follow-up visit.

We also evaluated patients attending their first scheduled visit to the dermatologist over a 6-month period (January 1, 2014 to June 30, 2014) in order to identify differences in the conditions seen.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 (IMB Corp). Qualitative variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test when necessary, that is, when the value in any of the cells in the contingency table was lower than 5. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

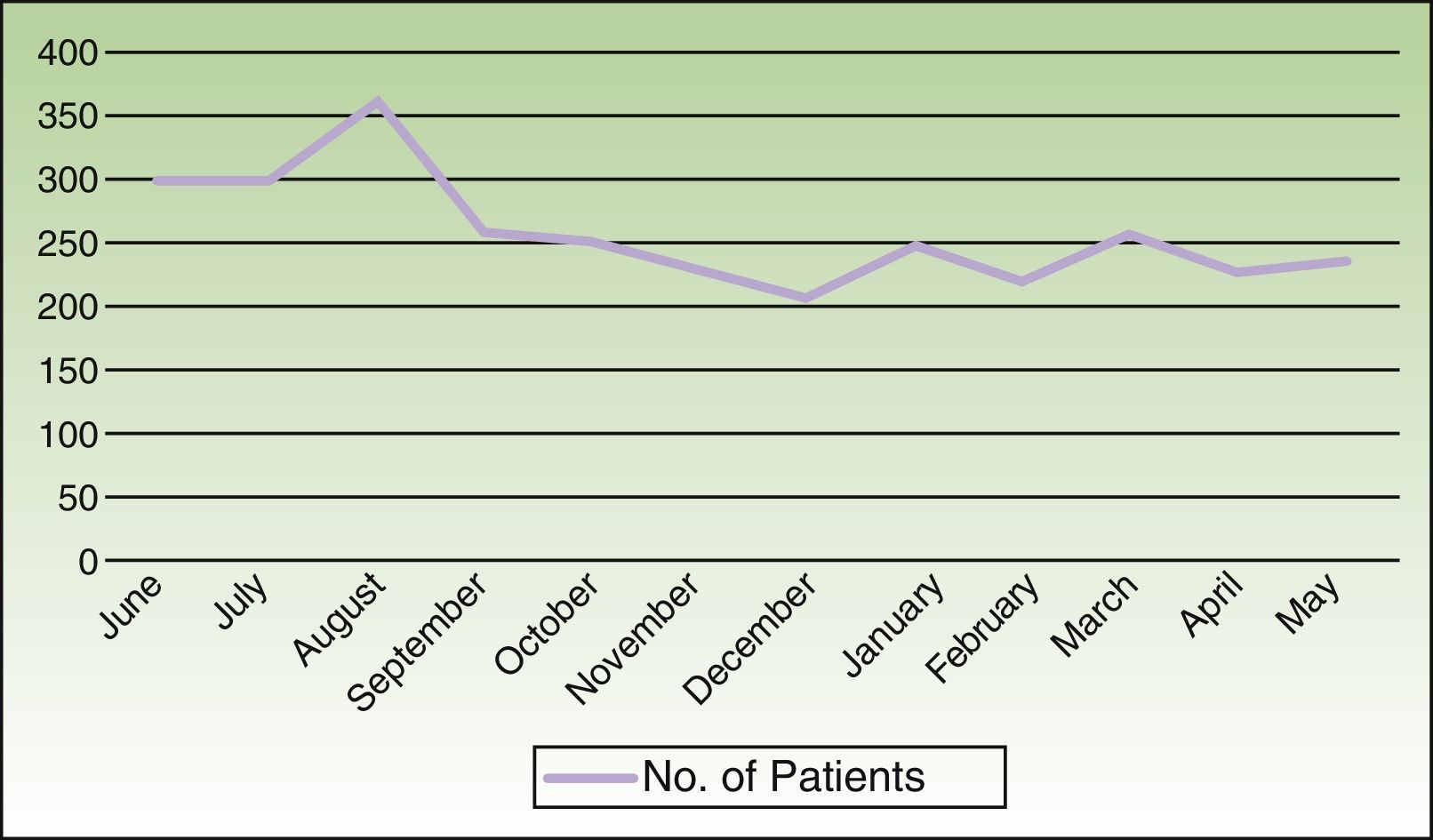

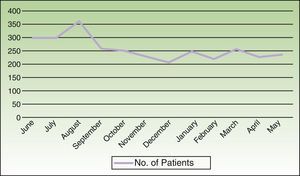

ResultsA total of 3084 patients were seen (8.45 patients/day), that is, 5.6% of all visits to our emergency department during the study period. The percentage of patients seen was significantly greater during the summer months (8%) than in the winter months (4%) (P=.0003). August was the month with the highest percentage of visits (11.6%), followed by June and July (Figure 1). Most visits were on Mondays (17.8%) and Fridays (16.3%).

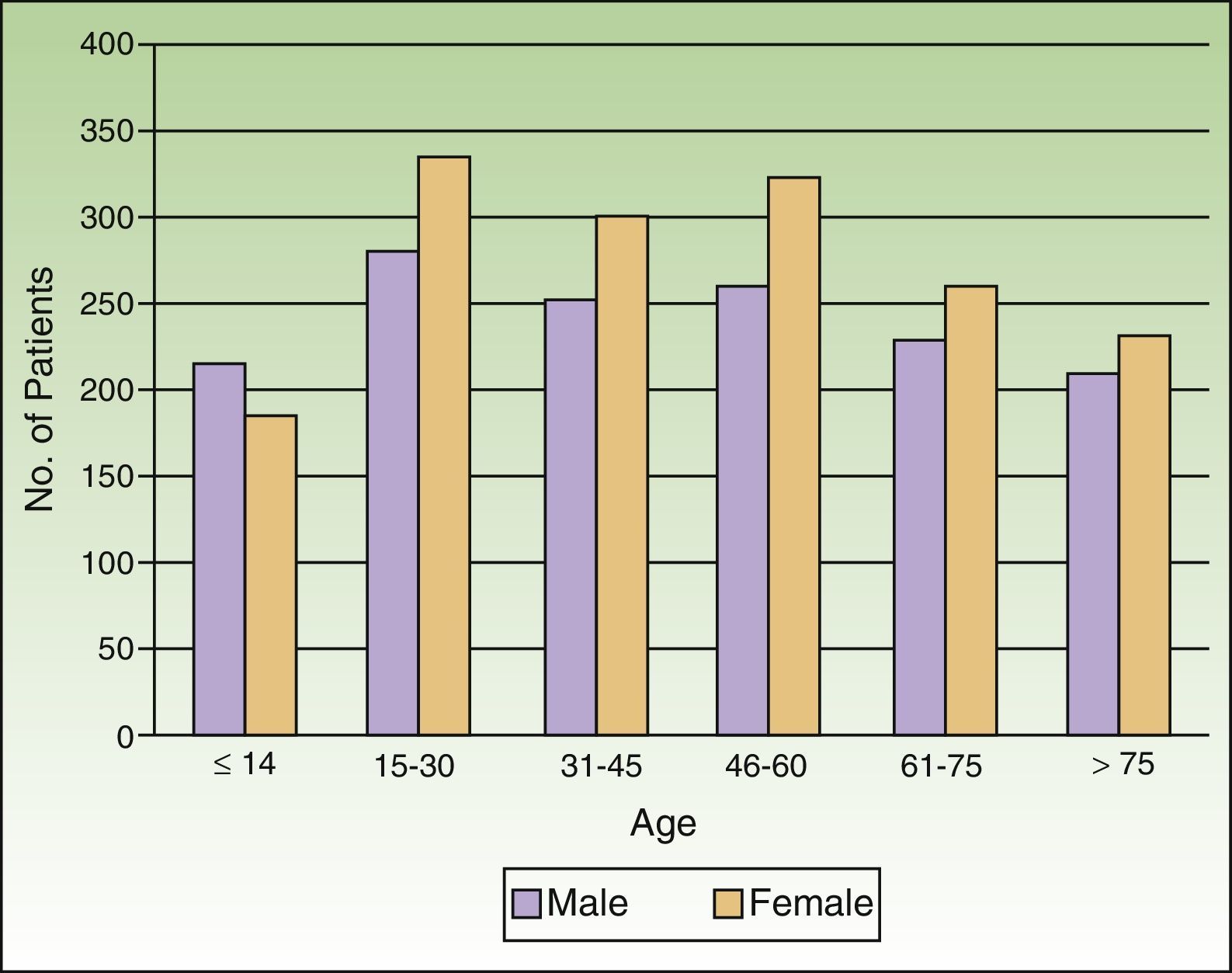

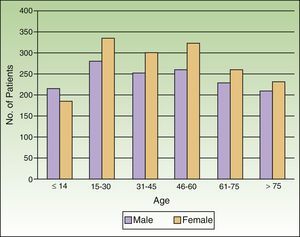

As for sex, 54.1% were female and 45.9% were male. The average age was 44 years (range, 1 month to 101 years). Children accounted for 13.4% of cases. Patients aged 14 to 69 years accounted for 68.3% of cases, and those aged over 69 accounted for 18.4%. Significantly more visits were recorded for women in all age ranges except children, among whom visits by boys were more common (P=.0003) (Figure 2).

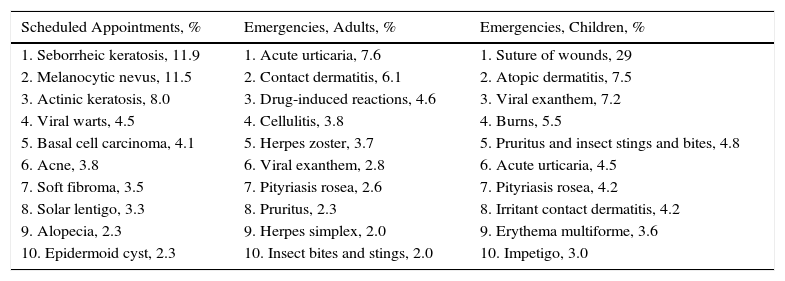

A total of 152 different diagnoses were made. The most frequent complaints were acute urticaria (7.6%), contact dermatitis (6.1%), drug-induced reactions (4.6%), cellulitis (3.8%), and herpes zoster (3.7%). The most frequent complaints in children were suture of a laceration (29%), atopic dermatitis (7.5%), viral exanthem (7.2%), burns (5.5%), pruritus and insect bites and stings (4.8%), and urticaria (4.5%) (Table 1).

Comparison of the 10 Most Common Conditions in Scheduled Appointments, Emergency Visits by Adults and Emergency Visits by Children.

| Scheduled Appointments, % | Emergencies, Adults, % | Emergencies, Children, % |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Seborrheic keratosis, 11.9 | 1. Acute urticaria, 7.6 | 1. Suture of wounds, 29 |

| 2. Melanocytic nevus, 11.5 | 2. Contact dermatitis, 6.1 | 2. Atopic dermatitis, 7.5 |

| 3. Actinic keratosis, 8.0 | 3. Drug-induced reactions, 4.6 | 3. Viral exanthem, 7.2 |

| 4. Viral warts, 4.5 | 4. Cellulitis, 3.8 | 4. Burns, 5.5 |

| 5. Basal cell carcinoma, 4.1 | 5. Herpes zoster, 3.7 | 5. Pruritus and insect stings and bites, 4.8 |

| 6. Acne, 3.8 | 6. Viral exanthem, 2.8 | 6. Acute urticaria, 4.5 |

| 7. Soft fibroma, 3.5 | 7. Pityriasis rosea, 2.6 | 7. Pityriasis rosea, 4.2 |

| 8. Solar lentigo, 3.3 | 8. Pruritus, 2.3 | 8. Irritant contact dermatitis, 4.2 |

| 9. Alopecia, 2.3 | 9. Herpes simplex, 2.0 | 9. Erythema multiforme, 3.6 |

| 10. Epidermoid cyst, 2.3 | 10. Insect bites and stings, 2.0 | 10. Impetigo, 3.0 |

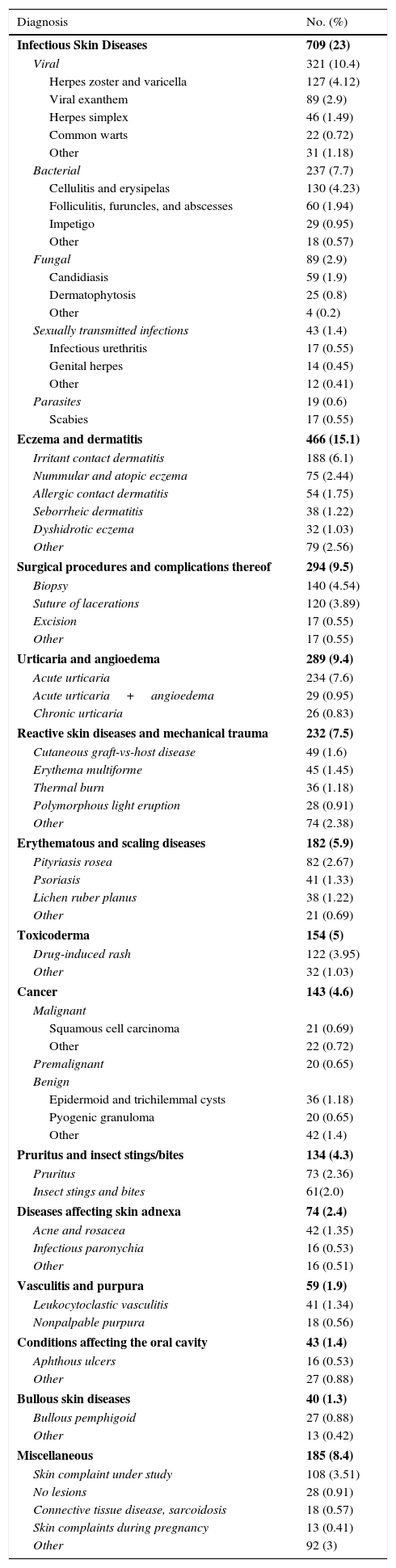

Given their large number, we classified diagnoses into 14 groups comprising similar complaints, including 1 group considered “nonclassifiable.” By group, the most common conditions in adults were infectious diseases (23%), eczema (15.1%), and dermatologic surgical procedures and complications thereof (9.5%) (Table 2). In children, the most common groups were infectious diseases (21%) and eczema (13%).

Diagnosis by Disease Group and Number and Percentage With Respect to the Total.

| Diagnosis | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Infectious Skin Diseases | 709 (23) |

| Viral | 321 (10.4) |

| Herpes zoster and varicella | 127 (4.12) |

| Viral exanthem | 89 (2.9) |

| Herpes simplex | 46 (1.49) |

| Common warts | 22 (0.72) |

| Other | 31 (1.18) |

| Bacterial | 237 (7.7) |

| Cellulitis and erysipelas | 130 (4.23) |

| Folliculitis, furuncles, and abscesses | 60 (1.94) |

| Impetigo | 29 (0.95) |

| Other | 18 (0.57) |

| Fungal | 89 (2.9) |

| Candidiasis | 59 (1.9) |

| Dermatophytosis | 25 (0.8) |

| Other | 4 (0.2) |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 43 (1.4) |

| Infectious urethritis | 17 (0.55) |

| Genital herpes | 14 (0.45) |

| Other | 12 (0.41) |

| Parasites | 19 (0.6) |

| Scabies | 17 (0.55) |

| Eczema and dermatitis | 466 (15.1) |

| Irritant contact dermatitis | 188 (6.1) |

| Nummular and atopic eczema | 75 (2.44) |

| Allergic contact dermatitis | 54 (1.75) |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 38 (1.22) |

| Dyshidrotic eczema | 32 (1.03) |

| Other | 79 (2.56) |

| Surgical procedures and complications thereof | 294 (9.5) |

| Biopsy | 140 (4.54) |

| Suture of lacerations | 120 (3.89) |

| Excision | 17 (0.55) |

| Other | 17 (0.55) |

| Urticaria and angioedema | 289 (9.4) |

| Acute urticaria | 234 (7.6) |

| Acute urticaria+angioedema | 29 (0.95) |

| Chronic urticaria | 26 (0.83) |

| Reactive skin diseases and mechanical trauma | 232 (7.5) |

| Cutaneous graft-vs-host disease | 49 (1.6) |

| Erythema multiforme | 45 (1.45) |

| Thermal burn | 36 (1.18) |

| Polymorphous light eruption | 28 (0.91) |

| Other | 74 (2.38) |

| Erythematous and scaling diseases | 182 (5.9) |

| Pityriasis rosea | 82 (2.67) |

| Psoriasis | 41 (1.33) |

| Lichen ruber planus | 38 (1.22) |

| Other | 21 (0.69) |

| Toxicoderma | 154 (5) |

| Drug-induced rash | 122 (3.95) |

| Other | 32 (1.03) |

| Cancer | 143 (4.6) |

| Malignant | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 21 (0.69) |

| Other | 22 (0.72) |

| Premalignant | 20 (0.65) |

| Benign | |

| Epidermoid and trichilemmal cysts | 36 (1.18) |

| Pyogenic granuloma | 20 (0.65) |

| Other | 42 (1.4) |

| Pruritus and insect stings/bites | 134 (4.3) |

| Pruritus | 73 (2.36) |

| Insect stings and bites | 61(2.0) |

| Diseases affecting skin adnexa | 74 (2.4) |

| Acne and rosacea | 42 (1.35) |

| Infectious paronychia | 16 (0.53) |

| Other | 16 (0.51) |

| Vasculitis and purpura | 59 (1.9) |

| Leukocytoclastic vasculitis | 41 (1.34) |

| Nonpalpable purpura | 18 (0.56) |

| Conditions affecting the oral cavity | 43 (1.4) |

| Aphthous ulcers | 16 (0.53) |

| Other | 27 (0.88) |

| Bullous skin diseases | 40 (1.3) |

| Bullous pemphigoid | 27 (0.88) |

| Other | 13 (0.42) |

| Miscellaneous | 185 (8.4) |

| Skin complaint under study | 108 (3.51) |

| No lesions | 28 (0.91) |

| Connective tissue disease, sarcoidosis | 18 (0.57) |

| Skin complaints during pregnancy | 13 (0.41) |

| Other | 92 (3) |

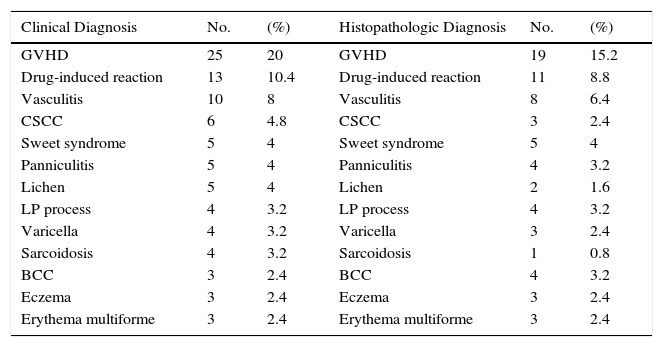

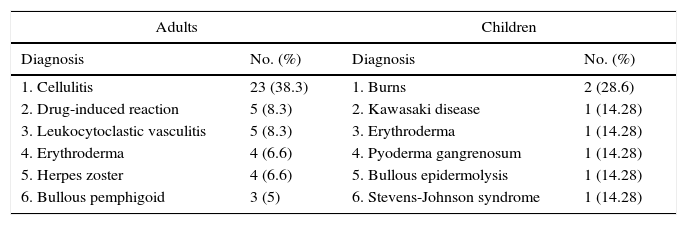

Overall, 290 special surgical procedures were performed (9.4%). The most frequent were skin biopsy in adults (140 biopsies) and suture of lacerations in children (120 sutures). Among patients who underwent biopsy, the most frequent condition was cutaneous graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) (20%), followed by drug-induced reactions (10.4%), and vasculitis (8%) (Table 3). A general analytic workup (complete blood count, biochemistry, and coagulation study) was ordered in 11.3% of patients. Serology testing was ordered for 5.9% and culture for 3.9%. Sixty patients had to be admitted to hospital (1.9% of the total), the most frequent diagnoses in adults being cellulitis (38%), drug-induced reactions (8%), and leukocytoclastic vasculitis (8%). Seven children were admitted to hospital. The most common reasons for admission are shown in Table 4. Patients were referred to the dermatology clinic for a follow-up visit in 42% of cases; the remaining 58% were discharged directly. The number of checkups was inversely proportional to the year of residency: second-year residents generated the highest percentage of referrals for a subsequent checkup (50%), followed by third-year residents (37%). Fourth-year residents generated the lowest percentage of follow-up visits (24%).

Most Frequent Clinical and Histopathologic Diagnoses Based on Emergency Biopsiesa

| Clinical Diagnosis | No. | (%) | Histopathologic Diagnosis | No. | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GVHD | 25 | 20 | GVHD | 19 | 15.2 |

| Drug-induced reaction | 13 | 10.4 | Drug-induced reaction | 11 | 8.8 |

| Vasculitis | 10 | 8 | Vasculitis | 8 | 6.4 |

| CSCC | 6 | 4.8 | CSCC | 3 | 2.4 |

| Sweet syndrome | 5 | 4 | Sweet syndrome | 5 | 4 |

| Panniculitis | 5 | 4 | Panniculitis | 4 | 3.2 |

| Lichen | 5 | 4 | Lichen | 2 | 1.6 |

| LP process | 4 | 3.2 | LP process | 4 | 3.2 |

| Varicella | 4 | 3.2 | Varicella | 3 | 2.4 |

| Sarcoidosis | 4 | 3.2 | Sarcoidosis | 1 | 0.8 |

| BCC | 3 | 2.4 | BCC | 4 | 3.2 |

| Eczema | 3 | 2.4 | Eczema | 3 | 2.4 |

| Erythema multiforme | 3 | 2.4 | Erythema multiforme | 3 | 2.4 |

Abbreviations: BCC, basal cell carcinoma; CSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; GVHD, graft-vs-host disease; LP, lymphoproliferative.

Most Frequent Diagnoses Leading to Hospitalization in Adults and Childrena

| Adults | Children | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | No. (%) | Diagnosis | No. (%) |

| 1. Cellulitis | 23 (38.3) | 1. Burns | 2 (28.6) |

| 2. Drug-induced reaction | 5 (8.3) | 2. Kawasaki disease | 1 (14.28) |

| 3. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis | 5 (8.3) | 3. Erythroderma | 1 (14.28) |

| 4. Erythroderma | 4 (6.6) | 4. Pyoderma gangrenosum | 1 (14.28) |

| 5. Herpes zoster | 4 (6.6) | 5. Bullous epidermolysis | 1 (14.28) |

| 6. Bullous pemphigoid | 3 (5) | 6. Stevens-Johnson syndrome | 1 (14.28) |

We also evaluated 1288 patients attending their first scheduled visit to the dermatology department. Women accounted for 60.8%, and the average age was 45 years. The most frequent diagnoses were seborrheic keratosis (11.9%), melanocytic nevus (11.5%), actinic keratosis (8%), viral warts (4.5%), and basal cell carcinoma (4.1%) (Table 1). During the study period, 21% of follow-up visits were via scheduled appointments.

DiscussionIn our study, dermatologic emergencies represented 5.6% of all visits to our emergency department (8-9 patients/day) and almost 8% of those seen during the summer months. These results are similar to those obtained at other centers, where 5-9 patients/day were seen for dermatologic emergencies,3,4 and lower than those of Grillo et al.,1 possibly because our catchment area is almost 3 times smaller. Consequently, dermatologic emergencies are a common reason for visits to the emergency department, and the incidence was similar in various provinces.

Visits were significantly more common during the summer months, especially August, in part owing to the increase in the number of complaints that are typical of summer (eg, insect bites and stings, polymorphous light eruption), worsening of photosensitive diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, porphyria cutanea tarda), and the decrease in the number of scheduled visits during the vacation period, with the resulting increase in the waiting list. Consistent with Grillo et al.,1 the emergency department was busiest on Mondays and Fridays. This finding can be explained by the closeness to the weekend: the absence of scheduled clinics and primary care or specialized care clinics generates uncertainty among patients, who are concerned about the course of their disease.

Women generally attended more than men, as reported elsewhere.1,3–5 In both our and in most other studies, this finding is explained by the greater concern among women over skin diseases.1,3,4,6 A significant difference was observed between the different age ranges and sex: in all age groups except children, women more frequently attended the emergency department than men. We believe that the high percentage of visits for lacerations in children (29%)—more likely in boys because of the games they play—could explain in part the greater incidence of males in this group.

The average age at the time of the visit was 44 years, which is consistent with the findings of other studies,7,8 although the type of patient varied widely, ranging from neonates to elderly persons.

Although the diagnoses were very varied (more than 150), thus illustrating the huge number of differential nuances in skin complaints, 65% were accounted for by 30 diseases. These findings are similar to those reported by González et al.,2 who found that 70% of their diagnoses were accounted for by 27 diseases. When the skin complaint is evaluated by nonspecialists, the number of diseases is considerably lower (96), with 21 diseases accounting for 84% of diagnoses.9 The group of infectious diseases and eczema account for almost 40% of all visits. The most frequent single diagnosis was acute urticaria, as reported elsewhere.3,8,9 In children, if we exclude lacerations, we also observe that infections (viral exanthem) and eczema were the main presenting complaints and that the most common single diagnosis was atopic dermatitis, as reported elsewhere.8,10

Our series included a high percentage of patients with GVHD owing to the large number of hematogenic progenitor cell transplants performed at our center. Almost 50% of patients who undergo allogenic hematogenic progenitor cell transplant can develop GVHD, and in a considerable percentage, this affects prognosis. Furthermore, cutaneous manifestations are sometimes the first sign of GVHD, and early diagnosis in such cases is essential if we are to start treatment quickly before other organs become severely affected or the skin disease becomes uncontrollable.11

Most dermatologic emergencies are not life-threatening, although morbidity and mortality are high in some diseases, for example, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis,12 and cancer, for which rapid diagnosis and therapy can improve survival (eg, melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma13,14).

Skin biopsy was the most frequent surgical procedure in adults (50%), followed by suture of lacerations—especially in children—which accounted for 40% of the total. The high percentage of sutures in children was due to the fact that, in our hospital, these cases are referred directly to the on-call dermatologist. Severe or catastrophic cases are managed in the plastic surgery department: in most cases, assistance is provided by the dermatology resident. Most biopsy specimens were taken for GVHD, followed by drug-induced reactions and vasculitis. We cannot compare our findings with those of other authors because published studies do not provide data on this finding.1–4 Less than 2% of patients had to be admitted to hospital; this percentage was similar to that reported elsewhere.1,3 Mean age was 65 years, which was higher than the mean age of patients visiting the emergency department. Most patients were men, in contrast with the clear predominance of women in other studies.1 Consistent with previous reports, the disease that most frequently required hospitalization was cellulitis/erysipela.9 As for testing, an urgent blood workup was necessary in 11.3% of cases, serology testing in 5.9%, and culture in 3.9%. Again, consistent with findings reported elsewhere, testing was for infections in most cases.1 In general, more tests are ordered when patients are seen by nonspecialists than when they are seen by dermatologists, as shown in the study by Maza et al.15 Furthermore, the scant correlation established between a presumptive diagnosis by nonspecialists and the confirmed diagnosis means that more additional tests are performed.16 In the absence of confirmatory prospective studies, these findings seem to indicate that the management of dermatologic emergencies is more cost-effective when patients are seen by specialists.

A follow-up visit was required in 42% of patients, which is similar to the 48% reported by Gil Mateo et al.6 and considerably different from the 13.4% reported by Valcuende et al.,3 who found that patients with skin complaints were seen by emergency department physicians.

Furthermore, if we take the residents’ training program into account, we find that the percentage of direct discharges increased with the year of residency, indicating better management of acute conditions and a gradual increase in knowledge. The most interesting emergency cases were selected by the supervisor and presented by the resident at the weekly clinical session for discussion of the diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of the case, thus enhancing specialist training in this type of disease.

We found that the age, sex, and presenting complaints of patients with scheduled dermatology appointments, were similar to those published elsewhere.17,18 When we compared these patients with those attending the emergency department with a skin complaint, we found that conditions differed between the 2 groups (Table 1), thus illustrating how residents in training need to see complaints other than those managed in the clinic to consolidate their knowledge of skin diseases.

Our study is clearly subject to a series of limitations owing to its descriptive design. Furthermore, even though we believe that in-house call plays a useful role in a resident's training, we think that it would be necessary to perform prospective cost-effectiveness studies to demonstrate the need for dermatology in-house call in tertiary institutions. Our study is also limited by the inclusion of suture of lacerations in children, given that this complaint is not a real dermatologic emergency, but a pediatric surgical emergency. These findings are hardly representative of other centers with dermatology in-house call.

ConclusionsThe most common types of dermatologic emergency seen at our hospital were infections, eczema, and urticaria. This finding is consistent with those of other studies in Spain.

Dermatology in-house call plays a useful role in the hospital, since it covers a large percentage of patients who come to the emergency department. These patients are assessed quickly, and additional tests are rarely necessary. Furthermore, the resident acquires clinical and surgical skills, takes on increasing responsibility, and becomes adept at the immediate management of dermatologic conditions, many of which are rarely seen at scheduled visits. The experience of managing dermatologic emergencies, therefore, is key to the integral training of the dermatology resident.

Finally, our findings are consistent with those of other authors, who found dermatology in-house call to be a valuable resource for our national hospital network. We defend the need to extend this service, especially if medical residents are trained at the center, as envisaged in the official training program for specialists.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of humans and animalsThe authors declare that no tests were carried out in humans or animals for the purpose of this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no private patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects referred to in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Bancalari-Díaz D, Gimeno-Mateos LI, Cañueto J, Andrés-Ramos I, Fernández-López E, Román-Curto C. Estudio descriptivo de urgencias dermatológicas en un hospital terciario. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:666–673.