The term cutaneous pseudolymphoma refers to benign reactive lymphoid proliferations in the skin that simulate cutaneous lymphomas. It is a purely descriptive term that encompasses various reactive conditions with a varied etiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, histology, and behavior. We present a review of the different types of cutaneous pseudolymphoma. To reach a correct diagnosis, it is necessary to contrast clinical, histologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular findings. Even with these data, in some cases only the clinical course will confirm the diagnosis, making follow-up essential.

El término pseudolinfoma cutáneo designa proliferaciones linfoides cutáneas benignas de naturaleza reactiva que simulan linfomas cutáneos. Se trata de un término puramente descriptivo que engloba diferentes entidades reactivas, con diversa etiología, patogénesis, presentación clínica, histología y comportamiento. En el presente artículo revisaremos los distintos tipos de pseudolinfoma cutáneo. Como veremos, para llegar al correcto diagnóstico de los mismos será preciso en cada caso la integración de los datos clínicos con los histopatológicos, inmunofenotípicos y moleculares. Incluso entonces, en ocasiones solo la evolución confirmará el diagnóstico, por lo que el seguimiento será esencial.

Cutaneous pseudolymphomas are benign reactive lymphoid proliferations that simulate cutaneous lymphomas clinically, histologically, or both clinically and histologically.1–6 The concept was described for the first time in 1891 by Kaposi under the name sarcomatosis cutis. Since then, these proliferations have received many names and the initial descriptions all corresponded to B-cell pseudolymphoma.4,5,7,8

Traditionally, cutaneous pseudolymphomas have been classified according to their histologic and immunophenotypic characteristics or rather in relation to the lymphoma they simulate. In other words, they are categorized as cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphomas or cutaneous T-cell pseudolymphomas, depending on the predominant lymphocytic component.9 While the distinction is frequently artificial, this classification system is still the widely used system for categorizing pseudolymphomas.

The list of cutaneous pseudolymphomas has grown in recent years with the inclusion of multiple reactive conditions with histopathologic features mimicking those of true lymphomas. It is also noteworthy that several entities that were originally considered to be cutaneous pseudolymphomas have since been reclassified as low-grade lymphomas based on clinical and pathologic findings, molecular biology studies, and follow-up data.6

Epidemiological data on cutaneous pseudolymphomas are scarce, although B-cell pseudolymphomas appear to be more common than their T-cell counterparts, and they are also more common in female patients.4,5,10 Cutaneous pseudolymphoma generally affects adults, although it can occur at any age. No familial cases have been reported.3

The proliferation of skin-associated lymphoid tissue (SALT), the cutaneous analog of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), following antigenic stimulation has been proposed as a contributory factor in the pathogenesis of cutaneous pseudolymphoma .11 Accordingly, cutaneous pseudolymphoma could potentially progress to a true cutaneous lymphoma with permanent antigenic stimulation, as occurs in the gastric mucosa in the presence of persistent Helicobacter pylori infection.12 However, while there have been some reports of progression to cutaneous lymphoma,13–17 true progression from a correctly diagnosed pseudolymphoma is very rare, if not impossible.

To diagnose cutaneous pseudolymphoma it is necessary to contrast clinical and histologic findings, with assessment of the architecture and composition of the inflammatory infiltrate, and to complement these findings with immunohistochemistry and gene rearrangement studies.6,18,19 These clonality studies generally reveal a polyclonal pattern. Nevertheless, it is not always possible to demonstrate clonality in true lymphomas, and certain pseudolymphomas have monoclonal B-cell and T-cell populations.5,8,20–26 Accordingly, although gene arrangement studies are useful, their results must be interpreted with caution and within the context of the data available.

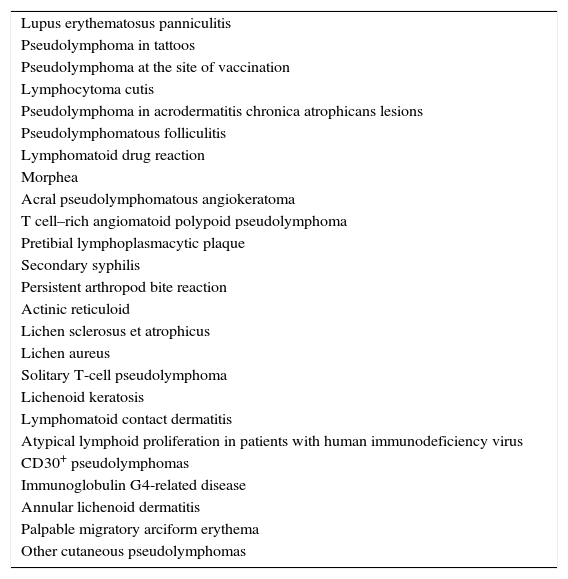

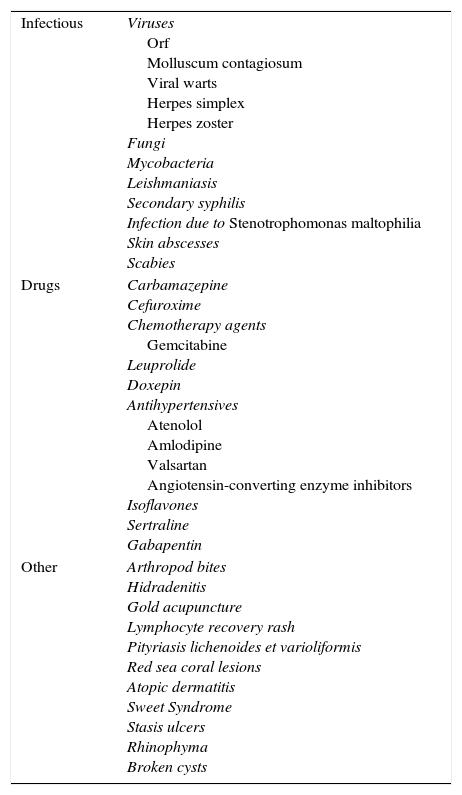

In the rest of this paper we will describe the main types of cutaneous pseudolymphoma (Table 1).

Cutaneous Pseudolymphoma.

| Lupus erythematosus panniculitis |

| Pseudolymphoma in tattoos |

| Pseudolymphoma at the site of vaccination |

| Lymphocytoma cutis |

| Pseudolymphoma in acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans lesions |

| Pseudolymphomatous folliculitis |

| Lymphomatoid drug reaction |

| Morphea |

| Acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma |

| T cell–rich angiomatoid polypoid pseudolymphoma |

| Pretibial lymphoplasmacytic plaque |

| Secondary syphilis |

| Persistent arthropod bite reaction |

| Actinic reticuloid |

| Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus |

| Lichen aureus |

| Solitary T-cell pseudolymphoma |

| Lichenoid keratosis |

| Lymphomatoid contact dermatitis |

| Atypical lymphoid proliferation in patients with human immunodeficiency virus |

| CD30+ pseudolymphomas |

| Immunoglobulin G4-related disease |

| Annular lichenoid dermatitis |

| Palpable migratory arciform erythema |

| Other cutaneous pseudolymphomas |

Lupus with subcutaneous involvement, a condition known as lupus erythematosus panniculitis, can raise clinical and particularly histologic suspicions of panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.6,27

Lupus erythematosus panniculitis presents as plaques or subcutaneous nodules in areas rarely affected by other forms of panniculitis, such as the face, the shoulders, and the proximal aspect of the arms. Antinuclear antibodies and other diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus may be absent.

Histologic examination shows a predominantly lobular panniculitis with dense lymphoid infiltrates in the deep dermis and the hypodermis, along with wide fibrous septae on occasions. The infiltrate is mixed, with abundant B cells, plasma cells, and clusters of plasmacytoid dendritic cells, frequently forming reactive germinal centers. The dermal-epidermal junction may show the characteristic interface dermatitis associated with the underlying connective tissue disease, and this is a key finding for the differential diagnosis. In lupus erythematosus panniculitis, unlike in panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, histology does not show cytophagocytosis or adipocyte rimming (atypical lymphoid cells surrounding the adipocytes). T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement will show a polyclonal pattern.6,27

Histologic features of panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma and lupus erythematosus panniculitis may, albeit rarely, overlap. In one study of 83 patients with panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, Willemze et al.28 observed abundant plasma cells interspersed with CD4+ T cells in 4 patients who also had lupus erythematosus, leading to an initial misdiagnosis of lupus erythematous panniculitis. The presence of cellular atypia together with a loss of pan-T-cell markers and/or clonal TCR-γ rearrangement was key to establishing a correct diagnosis.28

Pseudolymphoma in TattoosAlthough uncommon, pseudolymphomatous reactions to tattoo ink can occur, and a variable latency period has been described.29,30 Red ink is the most common ink involved in these reactions.30 Tattoo ink–related pseudolymphoma presents as subcutaneous nodules.11

Histologic examination shows a dense diffuse dermal infiltrate with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation composed mainly of small lymphocytes (most often T cells but there may also be B cells or a mixture) and macrophages. Additional findings include eosinophils, plasma cells, histiocytes, and giant multinucleated cells. These cells may form lymphoid follicles with germinal centers or patterns similar to those seen in mycosis fungoides. Spongiosis, exocytosis, and basal vacuolar degeneration may also be observed in the epidermis.29,30 The presence of macrophages phagocytizing the pigment is a key diagnostic clue.

Pseudolymphoma at the Site of VaccinationAn intense inflammatory response simulating cutaneous lymphoma can also occur at vaccination sites as the result of a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to vaccine components. This reaction is particularly seen in vaccines containing aluminum, as this metal contributes to the delayed absorption of other components, thereby prolonging the antigen stimulus.6,31 It presents as papules or superficial or deep erythematous nodules.6,32

The histologic pattern may be lichenoid, simulating mycosis fungoides, or nodular, simulating follicle center lymphoma (Fig. 1). In this second case, however, bcl-6+ cells will not be observed outside the reactive germinal centers.6,33 Clusters of CD30+ cells may occasionally be observed.33 When aluminum is involved, the histiocytes in the infiltrate, which may be solitary or arranged in clusters forming epithelioid granulomas, typically have abundant granular and basophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 2) corresponding to intracellular aluminum deposits.

Lymphocytoma cutis was first described by Spiegler in 1894. It is the prototype of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma and perhaps the most common variant. It represents an exaggerated local immune response to diverse stimuli, the most widely described of which are arthropod bites.6,32–37 One of the most classic associations is with the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi following a bite from a Ixodes tick.22,38

Lymphocytoma cutis typically presents as a solitary reddish nodule (Fig. 3) or less frequently as plaques or crops of papules. The face and neck are the most common sites of involvement. Lesions on the earlobe, nipples, or scrotum are highly characteristic of B burgdorferi–associated lymphocytoma cutis.6,38–40

Miliarial-type lesions have also been described, but less frequently. These present as multiple, symmetric, monomorphous translucent micropapules on the head and neck and they can be asymptomatic or slightly pruritic.11,41,42

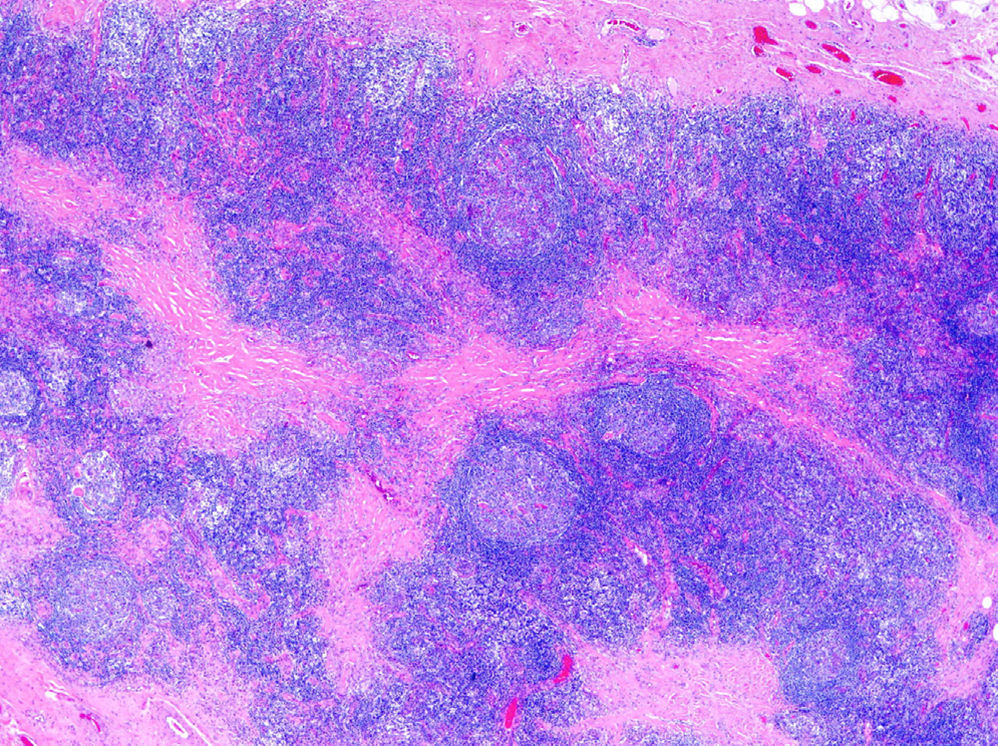

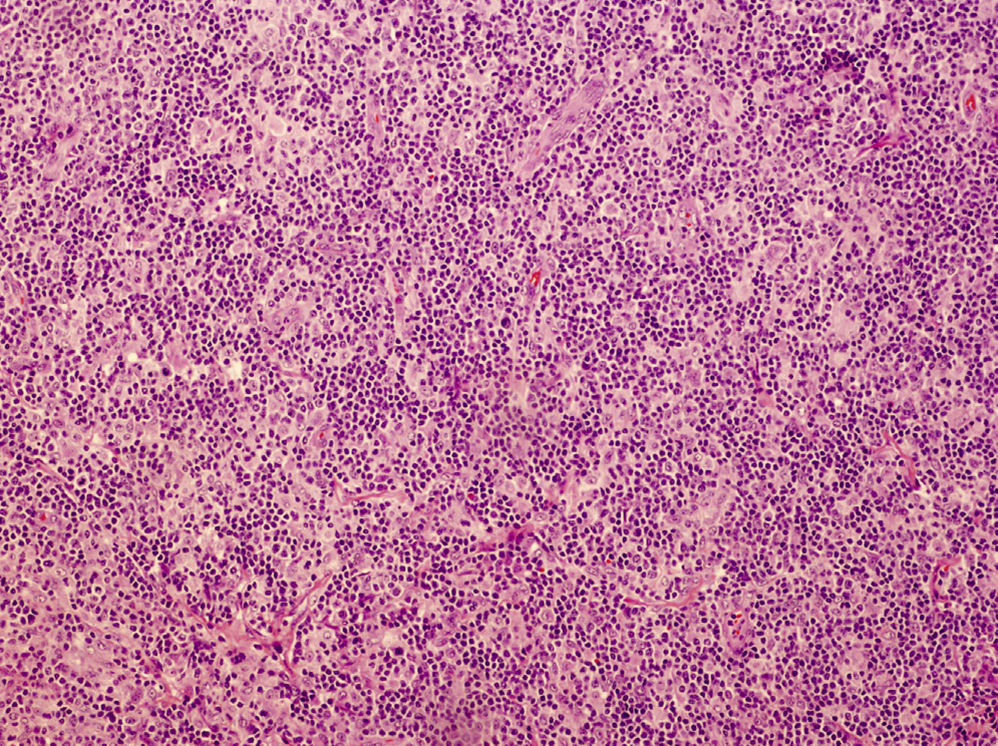

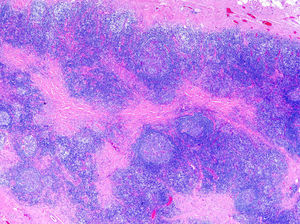

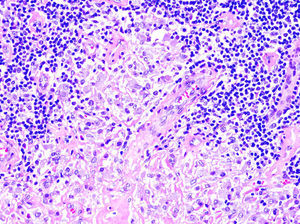

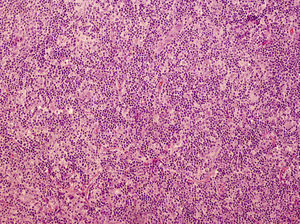

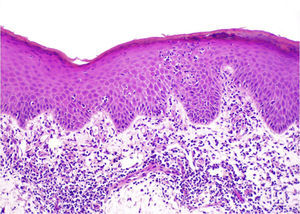

Histology reveals a dense nodular lymphoid infiltrate in the dermis, with germinal centers that characteristically lack a mantle zone and may merge. Although the infiltrate in pseudolymphomas tends to be top heavy (i.e., more pronounced in the superficial dermis) rather than bottom heavy like in lymphomas, in B burgdorferi–associated lymphocytoma cutis, infiltrates are often found throughout the dermis and even in the superficial layers of the subcutaneous tissue.6

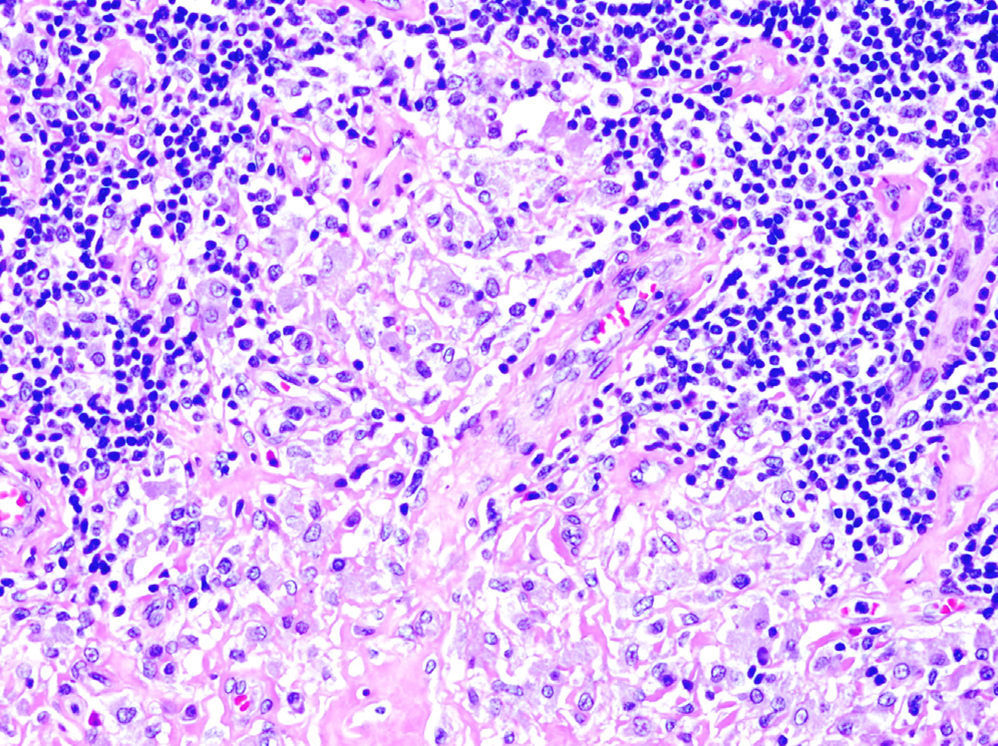

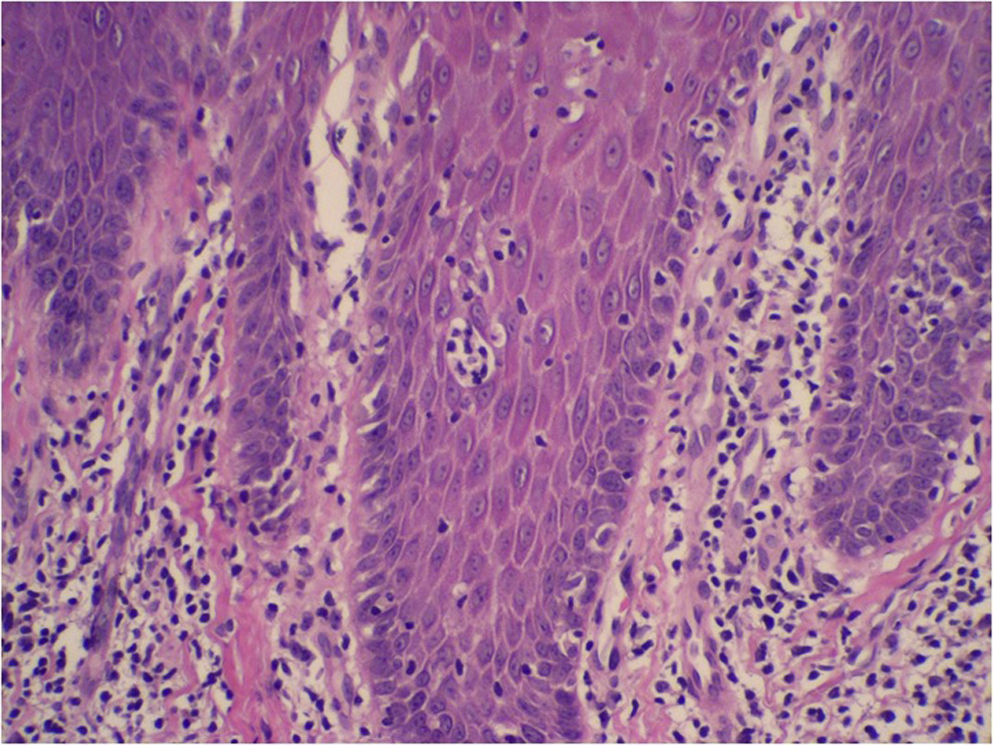

The infiltrate is formed by plasma cells, eosinophils, abundant reactive T cells, and tingible body macrophages (Fig. 4). This heterogeneity is another factor to take into account when distinguishing cutaneous pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas, as these tend to have a more uniform infiltrate. The predominant immunophenotype is a germinal center B-cell type, with positive staining for CD20, CD10, and bcl-6, and negative staining for bcl-2. The germinal centers tend to have a very high proliferative index, but unlike in true cutaneous lymphomas, cellular atypia and preservation of adnexal structures are not observed. Rearrangement analysis usually, but not always, shows a polyclonal pattern. Assessment of clonality in more than 1 lesion is very useful for differentiating pseudolymphomas and lymphomas in patients with several lesions. Detection of the same clone in 2 lesions or in the same lesion at different stages of development would point to a diagnosis of lymphoma.6,39,43

Histologic image of the lymphocytoma cutis shown in Figure 3. Dense mixed dermal infiltrate. Note the merging germinal centers devoid of the mantel zone, simulating a B-cell lymphoma (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×20).

Pseudolymphoma has been described in the lesions of patients with acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, which is a delayed cutaneous manifestation of B burgdorferi infection. Histologically, lesions can display 2 patterns: one simulating mycosis fungoides and the other (less frequent) one simulating cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. The rearrangement study shows a polyclonal infiltrate.44,45

Pseudolymphomatous FolliculitisPseudolymphomatous folliculitis is a cutaneous pseudolymphoma characterized by the presence of hyperplastic hair follicles together with a lymphoid infiltrate that can mimic cutaneous lymphoma. It presents with a single or, less frequently, several dome-shaped or nodular lesions on the face, scalp, or trunk.12,46

Histologically, pseudolymphomatous folliculitis can simulate small-to-medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma, follicle center B-cell lymphoma, or even folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. A dense lymphocytic infiltrate is located predominantly around the hair follicles, which show hyperplastic changes and thickened walls. Clusters of perifollicular S100+ and CD1A+ histiocytes may occasionally be seen. Rearrangement studies show a polyclonal infiltrate.11,12,46–50

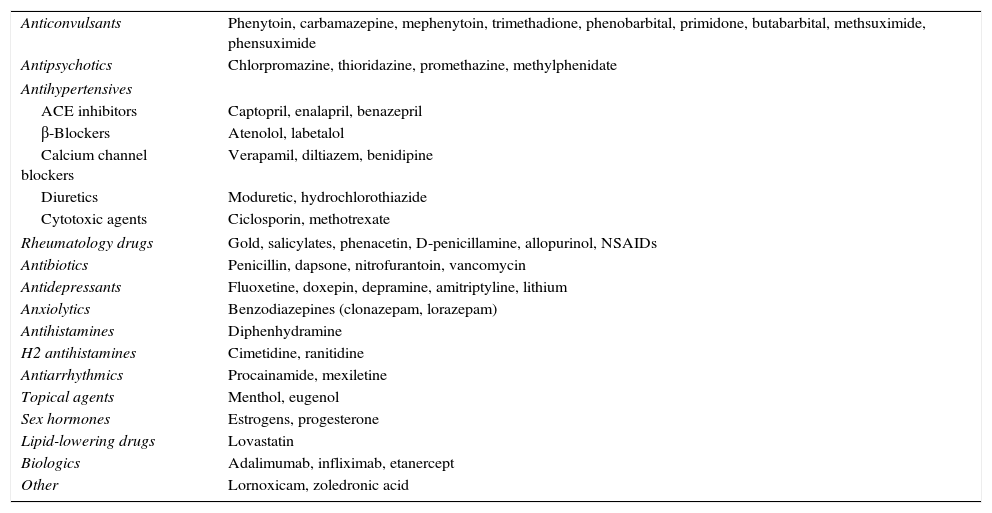

Lymphomatoid Drug ReactionNumerous drugs can induce cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates that resemble lymphoma clinically, histologically, or both clinically and histologically. The most frequently implicated drugs are anticonvulsants and antihypertensives, but others have been described (Table 2).

Drugs Associated With Pseudolymphomatous Cutaneous Reactions.

| Anticonvulsants | Phenytoin, carbamazepine, mephenytoin, trimethadione, phenobarbital, primidone, butabarbital, methsuximide, phensuximide |

| Antipsychotics | Chlorpromazine, thioridazine, promethazine, methylphenidate |

| Antihypertensives | |

| ACE inhibitors | Captopril, enalapril, benazepril |

| β-Blockers | Atenolol, labetalol |

| Calcium channel blockers | Verapamil, diltiazem, benidipine |

| Diuretics | Moduretic, hydrochlorothiazide |

| Cytotoxic agents | Ciclosporin, methotrexate |

| Rheumatology drugs | Gold, salicylates, phenacetin, D-penicillamine, allopurinol, NSAIDs |

| Antibiotics | Penicillin, dapsone, nitrofurantoin, vancomycin |

| Antidepressants | Fluoxetine, doxepin, depramine, amitriptyline, lithium |

| Anxiolytics | Benzodiazepines (clonazepam, lorazepam) |

| Antihistamines | Diphenhydramine |

| H2 antihistamines | Cimetidine, ranitidine |

| Antiarrhythmics | Procainamide, mexiletine |

| Topical agents | Menthol, eugenol |

| Sex hormones | Estrogens, progesterone |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | Lovastatin |

| Biologics | Adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept |

| Other | Lornoxicam, zoledronic acid |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Source: Ploysangam et al.,36 Naciri Bennani et al.,51 Imafuku et al.,52 Fukamachi et al.,53 Guis et al.,54 Stavrianeas et al.,55 Welsh et al.,56 Kitagawa et al.,57 Macisaac et al.,58 Kim et al.,59 Foley et al.60

Clinically, lymphomatoid drug reactions present as generalized papules, plaques, or nodules, or even erythroderma, sometimes with accentuation in sun-exposed areas.6,36,61 Lesions typically appear 2 to 8 weeks after the introduction of the offending drug, but later onset has been reported.36,42,62 The skin lesions may be accompanied by enlarged lymph nodes, fever, and less frequently hepatosplenomegaly, joint pain, and diverse blood test alterations including elevated liver enzymes and eosinophilia, particularly in cases due to anticonvulsants.61,63 Circulating Sézary cells may occasionally be detected.36

Histologic findings in lymphomatoid drug reaction include a band-like T cell–predominant infiltrate with epidermal spongiosis and exocytosis, simulating mycosis fungoides. On other occasions, there may be a nodular or diffuse B-cell pattern with formation of germinal centers, simulating follicle center or marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Cellular atypia has been described in some cases, as have abundant CD30+ cells, which can complicate diagnosis. Findings suggestive of lymphomatoid drug reaction include necrotic keratinocytes, red blood cell extravasation, pigmentary incontinence, dermal edema, absence of fibrosis in the papillary dermis, presence of other inflammatory cells in the infiltrate, and finally, negative clonality in the gene rearrangement study. Lesions in sun-exposed areas can also point to a diagnosis of lymphomatoid drug reaction.42,43,61,64–68

The condition resolves after a variable period of time on withdrawal of the drug and returns when it is reintroduced.42,43 There have been very rare reports of progression to true cutaneous lymphoma,69 and in these cases the skin lesions would not disappear after withdrawal of the drug.

MorpheaCollagen involvement is often not very evident in the inflammatory phase of connective tissue disorders, especially in localized scleroderma, and histology may reveal dense lymphoid infiltrates simulating cutaneous lymphoma and marginal zone B-cell lymphoma in particular. Plasma cells are almost always present and light chain gene rearrangement studies will show a polyclonal infiltrate.6,70,71 It is essential to contrast clinical and pathologic findings in such cases.

Acral Pseudolymphomatous Angiokeratoma/Small Papular PseudolymphomaAcral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma, which was originally described under the acronym APACHE (acral pseudolymphoma angiokeratoma in children), is a rare benign condition of unknown etiology and pathogenesis, although some authors believe it is a hypersensitivity reaction to insect bites.4,6,72,73 It is characterized by papules or clusters of asymptomatic red-purple nodules, typically located at acral sites, and is more common in children and adolescents.11,36,72–75

Histologic findings include a dense well-differentiated nodular B-cell and T-cell infiltrate that generally spares the adnexal structures, in addition to plasma cells, eosinophils, and on occasions histiocytes and giant multinucleated cells. A proliferation of capillary vessels may be observed. The epidermis is normally spared, although there have been reports of basal vacuolization, exocytosis, and spongiosis.6,72

T Cell–Rich Angiomatoid Polypoid PseudolymphomaT cell–rich angiomatoid polypoid pseudolymphoma has similar histologic findings to acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma, but it is characterized by solitary polypoid lesions at nonacral sites, with a predilection for the head and trunk. It typically affects young adults.11,76,77 Another difference between the 2 entities is that in angiomatoid polypoid pseudolymphoma, there is a predominance of CD4+ T cells in the infiltrate and the prominent thick-walled vessels seen in acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma are absent. Both entities must be distinguished from angioplasmacellular hyperplasia, in which the infiltrate is much richer in plasma cells.76–78

Pretibial Lymphoplasmacytic Plaque in ChildrenPretibial lymphoplasmacytic plaque is a benign chronic condition of unknown etiology that is probably reactive in nature. It presents as red-purple asymptomatic papules or well-delimited plaques that preferentially affect the anterior surface of the tibia in children. Histologically, it is similar to acral pseudolymphomatous angiokeratoma, although there is a much more pronounced presence of plasma cells, together with lymphocytes and prominent vessels. Vacuolization, exocytosis, and apoptotic bodies may be observed in the epidermis. The gene rearrangement study shows a polyclonal pattern.79–82

Secondary SyphilisHistology of secondary syphilis lesions and less frequently of primary or tertiary syphilis lesions may occasionally reveal a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate simulating marginal zone B-cell cutaneous lymphoma. The coexistence of interface/lichenoid dermatitis or granulomatous inflammation is an important diagnostic clue. Rearrangement studies show a polyclonal pattern and specific immunohistochemical staining for Treponema pallidum confirms the presence of these organisms. Lesions resolve quickly with antibiotic treatment. It is also worth noting that certain cases of malignant syphilis may also feature lesions that are clinically indistinguishable from lymphomatoid papulosis. The entities are also difficult to differentiate histologically, unless abundant plasma cells and spirochetes are observed.6,83,84

Persistent Arthropod Bite ReactionNodular scabies is the paradigm of persistent arthropod bite reaction, although this can be caused by arthropods other than the scabies mite. A delayed hypersensitivity reaction to a component of the mite has been implicated in the pathogenesis of the reaction, although it is rarely identified in lesions. Clinically, arthropod bite reaction presents as reddish papules or persistent pruritic nodules, despite adequate treatment.6,36

Histologically, nodular scabies may simulate mycosis fungoides, lymphomatoid papulosis, Hodgkin lymphoma, and in some cases, cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. The most frequent finding is a dense perivascular superficial and deep lymphoid infiltrate with predominant T cells, which are frequently CD30+, together with plasma cells, eosinophils, and prominent vessels.6,12,36,85,86

Actinic ReticuloidActinic reticuloid is a chronic photodermatitis that tends to affect elderly patients, and men in particular. It is characterized by extreme photosensitivity across a wide spectrum of UV radiation.6,36,43,87 Its pathogenesis remains unclear, although it has been proposed that a normal component of skin might become antigenic following alterations induced by a photoallergic reaction.88,89

In its early phases, actinic reticuloid presents as a highly pruritic eczematous dermatitis; there is a tendency towards localized lichenification in sun-exposed areas that may then spread to other areas.36,88 Histology reveals a mixed perivascular superficial or deep infiltrate that may include some atypical mononuclear cells. Actinic reticuloid can form a band-like pattern with lymphocytic exocytosis, simulating mycosis fungoides, or a more diffuse pattern, simulating peripheral T-cell lymphoma. The CD4/CD8 ratio, however, is lower in the case of actinic reticuloid.36,43,88

As the condition progresses, patients may develop erythroderma, enlarged lymph nodes, ectropion and up to 10% of Sézary cells in peripheral blood, complicating the differential diagnosis.6,36,90–92 Unlike mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, sensitivity to UV-B, UV-A, and even visible light is very high and can exacerbate the condition.88

Actinic reticuloid is a chronic condition that does not tend to resolve spontaneously.43,93 Sun-protection measures are essential, as is avoidance of implicated allergens.6

Lichen SclerosusGenital lichen sclerosus, particularly in its early phases, has histologic features that require consideration of mycosis fungoides in the differential diagnosis. Lesions show a dense band-like lymphoid infiltrate in the superficial dermis and marked epidermotropism.6,94 To confuse matters even further, gene rearrangement studies reveal a clonal pattern in a considerable number of cases.95,96 Cellular atypia is not generally seen in the infiltrate in lichen sclerosus, and intraepidermal lymphocytes tend to be located in the lower part of the epidermis, without pagetoid spread; interface changes are also common.94 It is essential to contrast clinical and pathologic findings.

Lichen AureusLichen aureus also has histologic features that can be confused with mycosis fungoides, and in some cases, there may be molecular evidence of clonality.6 Again, it is important to carefully correlate clinical and pathologic findings.

Solitary T-Cell PseudolymphomaSolitary T-cell pseudolymphoma is one of the most controversial variants of pseudolymphoma. With histologic features similar to those of mycosis fungoides and occasional monoclonality, this entity can present as superficial lesions on the breasts of adult women that resemble lichenoid keratosis lesions. In other cases, it appears as solitary nodular lesions with histologic findings similar to those of small- to-medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma. It follows an indolent course and excision is curative.6,97,98

Lichenoid KeratosisLichenoid keratosis is a benign epithelial tumor related to seborrheic keratosis and lentigines that affects elderly patients. It appears as small scaling plaques normally located on the trunk. Histologically, the findings can simulate those of mycosis fungoides, with a dense band-like lymphocytic infiltrate with a certain degree of epidermotropism and occasional monoclonality. Clinical-pathologic correlation is essential.6,99–101

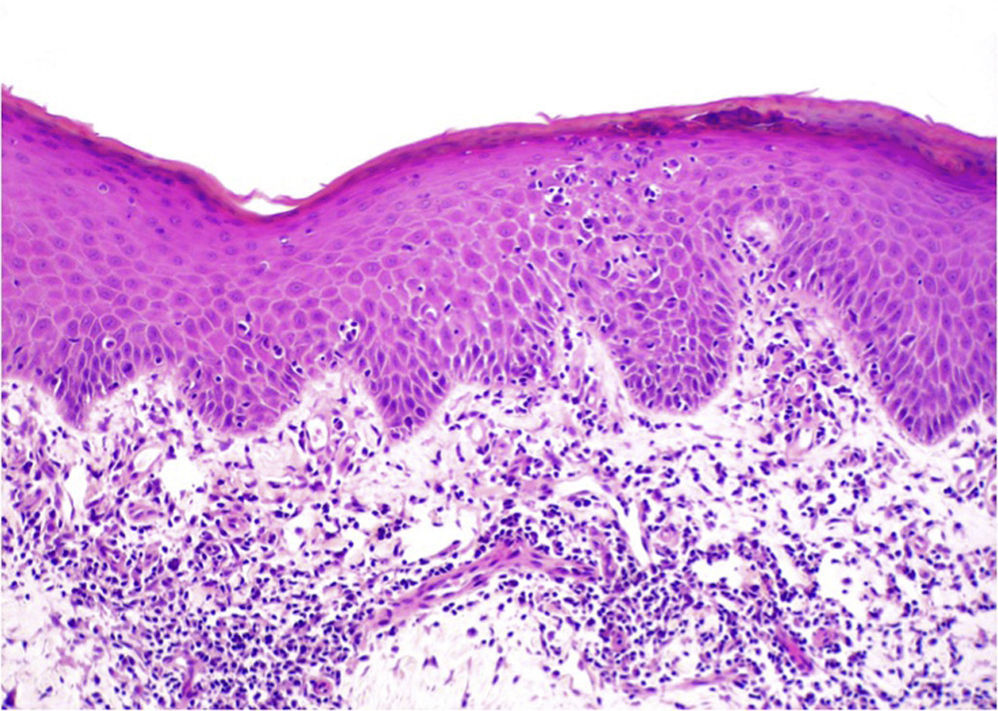

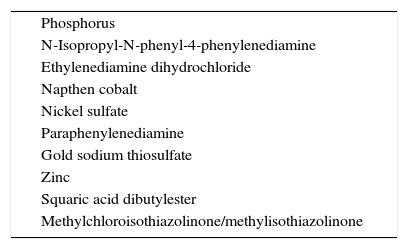

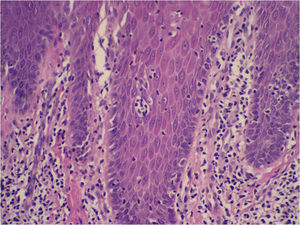

Lymphomatoid Contact DermatitisDescribed for the first time by Orbaneja et al.102 in 1976, lymphomatoid contact dermatitis has similar clinical and histopathologic features to mycosis fungoides. It presents as pruritic erythematous plaques, with an oscillating course, and is more common in middle-aged men.102–104 Histology shows a band-like T cell–predominant infiltrate component and epidermotropism (Fig. 5). However, in the epidermis there may be spongiosis or microvesiculation; cellular atypia is very low and there is no evidence of Pautrier microabscesses, although it is not uncommon to see small collections of keratinocytes intermixed with Langerhans cells and some lymphocytes that are frequently confused with keratinocytes (Fig. 6). TCR rearrangement studies generally show a polyclonal infiltrate.43,94,103,104

Table 3 shows the allergens that have been implicated in lymphomatoid contact dermatitis.102,105–115 Patch tests show sensitization103 and the condition resolves with avoidance of exposure to causative allergens.6

Allergens Implicated in Lymphomatoid Contact Dermatitis.

| Phosphorus |

| N-Isopropyl-N-phenyl-4-phenylenediamine |

| Ethylenediamine dihydrochloride |

| Napthen cobalt |

| Nickel sulfate |

| Paraphenylenediamine |

| Gold sodium thiosulfate |

| Zinc |

| Squaric acid dibutylester |

| Methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone |

Atypical CD8+ lymphoid proliferation is a polyclonal lymphoproliferative disorder with an apparently reactive nature that is clinically and histologically similar to T-cell lymphoma and affects individuals with human immunodeficiency virus infection, particularly when they are severely immunocompromised. Its pathogenesis is unknown.116

Clinically, it presents as a generalized pruritic rash frequently associated with pigment changes (hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation) and lichenification. Lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, eosinophilia, and, on occasions, circulating Sézary cells have also been described.116–118

The histologic features resemble those of mycosis fungoides, but there is a predominance of CD8+ lymphocytes. Clonality studies are negative.116,119–121

CD30+ T-Cell PseudolymphomaThe presence of large atypical CD30+ T cells has been described in numerous reactive skin disorders in recent years (Table 4). In these pseudolymphomas, CD30+ cells do not form clusters but are rather distributed throughout the infiltrate. Rearrangement studies show a polyclonal pattern. Histology frequently shows evidence of the underlying condition.6,122

Pseudolymphomatous Disorders With Possible CD30+ Cell Proliferation.

| Infectious | Viruses Orf Molluscum contagiosum Viral warts Herpes simplex Herpes zoster Fungi Mycobacteria Leishmaniasis Secondary syphilis Infection due to Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Skin abscesses Scabies |

| Drugs | Carbamazepine Cefuroxime Chemotherapy agents Gemcitabine Leuprolide Doxepin Antihypertensives Atenolol Amlodipine Valsartan Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors Isoflavones Sertraline Gabapentin |

| Other | Arthropod bites Hidradenitis Gold acupuncture Lymphocyte recovery rash Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis Red sea coral lesions Atopic dermatitis Sweet Syndrome Stasis ulcers Rhinophyma Broken cysts |

Immunoglobulin (Ig) G4-related sclerosing disease is characterized by a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate featuring IgG4+ plasma cells, together with sclerotic changes and elevated IgG4 serum levels (>135mg/dL).128

Skin involvement is rare, but it can occur in isolation and without elevated serum IgG4 titers. IgG4-related sclerosing disease presents as plaques or as solitary or multiple nodules on the head and/or extremities of middle-aged, predominantly male, adults.129–132

Histology shows a mixed inflammatory infiltrate immersed in a sclerotic stroma in the dermis, and occasionally in the subcutaneous tissue.11,128,130 An IgG4 to total IgG ratio of above 40% is highly suggestive of IgG4-related sclerosing disease.128

Annular Lichenoid DermatitisAnnular lichenoid dermatitis is an entity of unknown pathogenesis, initially described in children, that shares many histologic and immunophenotypic characteristics with mycosis fungoides. It presents as solitary or multiple asymptomatic reddish-brown annular plaques with raised borders on the trunk.

Histologic examination shows a band-like CD8+-predominant lymphocytic infiltrate, vacuolar degeneration at the dermal-epidermal junction, and necrotic keratinocytes at the tips of the rete ridges. Marked epidermotropism, Pautrier microabscesses, and fibrosis in the papillary dermis are not observed. Monoclonality is shown to be absent by rearrangement studies.133–135

Palpable Migratory Arciform ErythemaPalpable migratory arciform erythema is an uncommon entity that presents with erythematous annular plaques located predominantly on the trunk with a centrifugal distribution; the lesions tend to disappear within days or weeks. Histologically there is a perivascular and periadnexal CD4+-predominant lymphocytic infiltrate, without epidermal involvement, plasma cells, or interstitial mucin. A polyclonal pattern is detected by gene rearrangement studies in most cases.136,137

Other Cutaneous PseudolymphomasOther cutaneous pseudolymphomas can also simulate cutaneous lymphomas clinically and/or histologically.

In the inflammatory phase of vitiligo, which is characterized by erythematous, scaling plaques rather than achromic patches, histology can reveal a dense band-like lichenoid infiltrate with lymphocytic exocytosis simulating mycosis fungoides in the lower part of the epidermis. Most of the cells are CD8+. Follow-up is essential.138

There have also been reports of pseudolymphomas in relation to herpes simplex and herpes zoster infections that can mimic T-cell or B-cell lymphomas or CD30+ lymphoproliferative diseases.139

Atypical cells have also been described in cases of chronic discoid lupus erythematosus.6 Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin can also be histologically confused with B-cell lymphoma. Polyclonal infiltrates and CD123+ plasmacytoid monocytes can help to distinguish between these disorders.43,140

The true nature of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) is still a matter of debate. PLEVA is a generally benign condition and is probably a reactive disorder with an infectious or inflammatory origin.141–143 However, there have been reports of monoclonal rearrangement141 and, at least in the febrile ulceronecrotic form, an association with cytotoxic cutaneous lymphoma has been considered. The 2 entities have overlapping clinical and histologic findings, although infiltrates are not as dense or as deep in PLEVA, and cellular atypia is also less pronounced.144 Follow-up is particularly important in PLEVA.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank Dr Jaime Guijarro, Dr Jose Carlos Pascual, Dr Javier Mataix, Dr Juan Francisco Silvestre, and Dr María Niveiro for contributing to this article through reports of their cases and experiences.

Please cite this article as: Romero-Pérez D, Blanes Martínez M, Encabo-Durán B. Pseudolinfomas cutáneos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:640–651.