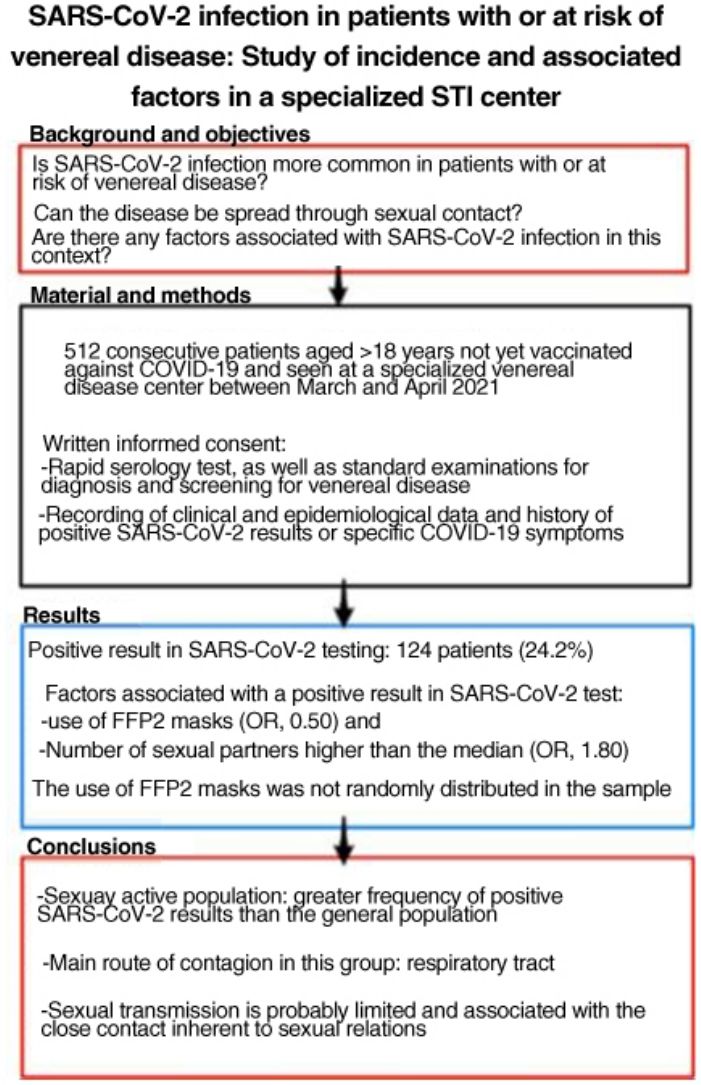

SARS-CoV-2 is more easily spread by close contact, which is inherent to sexual intercourse. People with, or at risk for, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) may therefore have higher rates of COVID-19. The aim of this study was to estimate SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in people seen at a dedicated STI clinic, compare our findings to the estimated seroprevalence in the local general population, and study factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in this setting.

Material and methodsCross-sectional observational study including consecutive patients older than 18 years of age who had not yet been vaccinated against COVID-19 and who underwent examination or screening at a dedicated municipal STI clinic in March and April 2021. We ordered rapid SARS-CoV-2 serology and collected information on demographic, social, and sexual variables, STI diagnoses, and history of symptoms compatible with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

ResultsWe studied 512 patients (37% women). Fourteen (24.2%) had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test. Variables associated with positivity were use of FFP2 masks (odds ratio 0.50) and a higher-than-average number of sexual partners (odds ratio 1.80). Use of FFP2 masks was not randomly distributed in this sample.

ConclusionsSexually active members of the population in this study had a higher incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection than the general population. The main route of infection in this group appears to be respiratory, linked to close contact during sexual encounters; sexual transmission of the virus is probably limited.

El SARS-CoV-2 se transmite con más facilidad por cercanía física, inherente a las relaciones sexuales, lo que ha hecho plantearse que pueda haber una mayor incidencia de COVID-19 en personas con infecciones venéreas o de transmisión sexual (ITS) o en riesgo de adquirirlas. Por este motivo, buscamos estimar la seroprevalencia de anticuerpos frente a SARS-CoV-2 en personas que acuden a una consulta monográfica de ITS, comparar dicha seroprevalencia con la estimada en nuestra región y estudiar los factores asociados.

Material y métodoEstudio observacional transversal que incluye a pacientes mayores de 18 años aún no vacunados atendidos en una consulta monográfica municipal de ITS para estudio o cribado, incluidos de forma consecutiva de marzo a abril de 2021. Se realizó test serológico rápido para SARS-CoV-2, y se recogieron variables demográficas, sociales y sexuales, diagnósticos de ITS y antecedentes de síntomas compatibles con infección por SARS-CoV-2.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 512 pacientes, el 37% mujeres. Ciento veinticuatro pacientes (24,2%) tuvieron alguna prueba positiva a SARS-CoV-2. Se relacionaron con un resultado positivo: el uso de mascarillas tipo FFP2 (OR: 0,50) y el número de parejas sexuales superior a la mediana (OR: 1,80). El uso de mascarillas FFP2 no se distribuyó de manera aleatoria en la muestra.

ConclusionesLa población sexualmente activa ha tenido pruebas positivas a SARS-CoV-2 con más frecuencia que la población general. La principal vía de contagio en este grupo parece ser la vía respiratoria, por lo que la transmisión sexual es probablemente limitada y está relacionada con la proximidad que implican las relaciones sexuales.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus spreads mainly via airborne transmission in viral particles eliminated during breathing, coughing, or sneezing. It can also be transmitted by direct contact with the conjunctival, nasal, and oral mucosa via the hands or fomites.1 These main routes of transmission would largely account for many of the cases occurring because of sexual relations, which necessarily involve close physical contact.

A systematic review published in April 2021 stated that SARS-CoV-2 could not be considered a sexually transmissible virus.2 However, data now indicate that the virus could also be spread via sexual contact. On the one hand, viral RNA has been detected in samples of saliva and oral mucosa.3 Moreover, the cells of the oral mucosa and pharynx may be more susceptible to infection, since they express angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors, indicating that infection can be transmitted by kissing, although this probably plays a lesser role in the context of respiratory transmission.4 On the other hand, RNA has also been detected in cells from the intestinal and rectal mucosa, and there have been reports of elimination of the virus in feces, where it has been reported to remain longer than in the respiratory tract.5,6 In addition, viral RNA has been detected in the vagina,7 and the possibility—albeit low—of mother-to-child transmission has been discussed.8 Nevertheless, during the early phases of the pandemic, viral RNA was not detected in the semen of men in the acute phase of the infection, men in the recovery phase, or in samples of testicular tissue from a man who died from COVID-19.9 The sexually active population is a particularly interesting group in terms of the study of possible sexual transmission.

Therefore, we might consider that persons with multiple sexual contacts, especially those involved in commercial sex work, could be at a greater risk of COVID-19,10 both through possible sexual transmission and through the physical proximity inherent to sexual relations.11 The economic crisis associated with the COVID-19 epidemic, which was particularly striking in the city of Madrid,12 may have increased the vulnerability of specific groups, such as commercial sex workers,13,14 by pushing them to assume the risk of infection (i.e., of SARS-CoV-2 infection itself and of sexually transmitted infection [STI]).

Various preventive measures were implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic. Before the vaccine became available, many measures focused on social distancing and restriction of movement. Evaluating protective methods is generally useful in the postcrisis learning curve. Sexually active groups may be characterized by specific behaviors with respect to restrictions and preventive measures. This is relevant when proposing targeted messages and measures.

The objectives of the present study were as follows: to estimate the seroprevalence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in sexually active persons seen at an STI clinic; and to analyze the social and preventive factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Material and MethodsWe performed a cross-sectional observational study of all patients aged ≥18 years seen at a dedicated STI clinic (for assessment or screening, regardless of whether they had symptoms of STI) and not vaccinated against COVID-19. The patients gave their written informed consent to be included in the study between March 10 and April 21, 2021. The sample size for estimation of seroprevalence was calculated at 500 patients using Epi-Info (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

In addition to the standard diagnostic examinations necessary for assessment or screening of STI, participants were interviewed to determine demographic, epidemiologic, and behavioral variables. They also underwent a rapid test for qualitative detection of immunoglobulin (Ig) G and M against SARS-CoV-2 (Joysbio Technology, lot no. 2020033006, with 92.4% sensitivity and 94.4% specificity according to the studies made at the time of acquisition) from capillary blood obtained by finger puncture. If the result led to a suspected active SARS-CoV-2 infection, an antigen detection test was performed.

A probable history of SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined based on the reactivity of the rapid serology test or on a previous positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 within the time frame of the pandemic. For the purpose of additional analyses, the previous 2 criteria were extended to include the presence of symptoms compatible with COVID-19. Apart from demographic variables such as country of origin, age, and sex, we collected behavioral variables such as sexual orientation, number of sexual partners, commercial sex work, alcohol consumption, chemsex,15 use of a mask during sexual relations, and type of mask generally worn.

The hard copy case report form was recoded on an anonymized spreadsheet for data management. The study was approved by the Drug Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitario de la Princesa (registry no. 4401, code COVID19, approved 25-02-21, CEIm code 04/21).

The statistical analysis was performed using R, version 4.1.2. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency, age was expressed as mean (SD), and the number of sexual partners as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Hypotheses were assessed using the χ2 test for categorical variables, the t test for age, and the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test for the number of sexual partners. Two binary logistic regression models were fitted for SARS-CoV-2 infection: the main one, using seropositivity in the rapid test or previous positive test results as the dependent variable, and another, in which the dependent variable was the presence of compatible symptoms. Since it was not possible to collect the number of sexual partners for some commercial sex workers, the missing values were imputed with the group median.

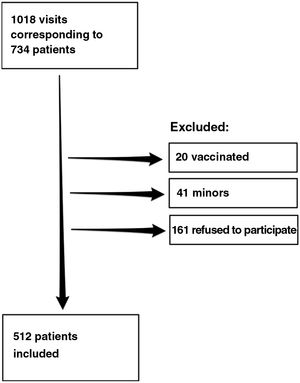

ResultsDuring the study period, we recorded 1018 visits to the clinic by 734 patients, of whom 512 agreed to participate in the study. Fig. 1 shows the flow chart for inclusion of patients.

A total of 124 patients (24.2%) had a positive result in the rapid serology test or positive SARS-CoV-2 test results during the previous year. Taken together with patients who had COVID-19 symptoms who did not undergo testing, this figure rose to 208 patients (40.7%). The rapid serology tests were positive in 24 patients, 23 of whom had positive IgG and 1 positive IgM and a negative result in the rapid antigen test.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants and their behaviors overall and according to the finding of a positive serology result for coronavirus.

Characteristics of Participants Overall and By Coronavirus Test Results.

| Overall | Negative test result | Positive test result | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 512 | 388 | 124 | |

| Mean (SD) age, y | 32.88 (9.21) | 32.77 (9.04) | 33.20 (9.76) | .652 |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 190 (37.1) | 143 (36.9) | 47 (37.9) | .918 |

| European origin, No. (%) | 307 (60.0) | 237 (61.1) | 70 (56.5) | .417 |

| Sexual orientation, No. (%) | .648 | |||

| Heterosexual | 253 (49.4) | 196 (50.5) | 57 (46.0) | |

| Homosexual | 238 (46.5) | 177 (45.6) | 61 (49.2) | |

| Bisexual | 21 (4.1) | 15 (3.9) | 6 (4.8) | |

| Commercial sex work, No. (%) | 71 (13.9) | 50 (12.9) | 21 (16.9) | .324 |

| Risky alcohol consumption, No. (%) | 31 (6.1) | 25 (6.4) | 6 (4.8) | .663 |

| Drug use, No. (%) | .779 | |||

| No | 387 (75.6) | 291 (75.0) | 96 (77.4) | |

| Yes, not IDU | 122 (23.8) | 95 (24.5) | 27 (21.8) | |

| Yes, also IDU | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Chemsex, No. (%) | 40 (7.8) | 30 (7.7) | 10 (8.1) | 1 |

| Sex with non-cohabitants during lockdown (%) | 55 (10.7) | 43 (11.1) | 12 (9.7) | .785 |

| Condom use, No. (%) | 183 (35.7) | 138 (35.6) | 45 (36.3) | .969 |

| FFP2 mask, No. (%) | 118 (23.0) | 101 (26.0) | 17 (13.7) | .007 |

| Median (IQR) No. of sexual partners during the previous 3 months | 2.00 (1–8) | 2.00 (1–6) | 3.00 (1–10) | .016 |

| Median (IQR) No. of sexual partners during the previous year | 6.00 (2–30) | 5.00 (2–20) | 10.00 (3–40) | .013 |

| Symptoms compatible with COVID-19, No. (%) | 208 (40.6) | 84 (21.6) | 124 (100.0) | .001 |

Abbreviations: IDU, injecting drug use; IQR, interquartile range.

The bivariate analysis showed that a positive serology result was associated with the use of masks other than FFP2 and the number of sexual partners. The type of mask used was not randomly distributed in the sample: FFP2 or similar masks were less frequently used by non-Europeans and commercial sex workers. Moreover, mean age was slightly higher in persons who used FFP2 or similar masks. We found no association between the type of mask used and the reasons for wearing a mask (e.g., to avoid being fined) or use of a mask during sexual relations (Table 2).

Description of the Population and Analysis of Factors Associated with the Main Type of Mask Used.

| Overall | No FFP2 | FFP2 or similar | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 512 | 394 | 118 | |

| Mean (SD) age, y | 32.88 (9.21) | 32.40 (8.93) | 34.48 (9.97) | .031 |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 190 (37.1) | 149 (37.8) | 41 (34.7) | .619 |

| European origin, No. (%) | 307 (60.0) | 213 (54.1) | 94 (79.7) | <.001 |

| Sexual orientation, No. (%) | .391 | |||

| Heterosexual | 253 (49.4) | 201 (51.0) | 52 (44.1) | |

| Homosexual | 238 (46.5) | 178 (45.2) | 60 (50.8) | |

| Bisexual | 21 (4.1) | 15 (3.8) | 6 (5.1) | |

| Commercial sex work, No. (%) | 71 (13.9) | 63 (16.0) | 8 (6.8) | .017 |

| Condom use, No. (%) | 183 (35.7) | 136 (34.5) | 47 (39.8) | .344 |

| Use of mask mainly to avoid being fined, No. (%) | 103 (20.1) | 82 (20.8) | 21 (17.8) | .558 |

| Use of mask during sexual relations, No. (%) | .222 | |||

| Never | 471 (92.0) | 358 (90.9) | 113 (95.8) | |

| In some cases, although not for the whole duration of the act | 27 (5.3) | 24 (6.1) | 3 (2.5) | |

| In almost all cases, for almost the whole duration of the act | 14 (2.7) | 12 (3.0) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Median (IQR) No. of sexual partners in the previous 3 mo | 2.00 (1–8) | 3.00 (1–10) | 1.00 [1–3] | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) No. of sexual partners in the previous year | 6.00 (2–30) | 7.00 (2–40) | 4.00 (2–10) | .001 |

| Previous positive SARS-CoV-2 result, No. (%) | 124 (24.2) | 107 (27.2) | 17 (14.4) | .007 |

| History of symptoms compatible with COVID-19, No. (%) | 208 (40.6) | 177 (44.9) | 31 (26.3) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

One specific subgroup comprised the 71 commercial sex workers. Of these, 80% were cisgender women, 11 cisgender men, and 8.5% transgender women. Non-Europeans accounted for 94.4% and Europeans for 5.6%. Only 11.3% used FFP2 or similar masks. The reason for wearing the mask was to avoid fines in 19.7%, which was similar for the rest of the sample. The median number of sexual partners was 80 in the previous 3 months and 270 in the previous year, clearly higher than for the rest of the sample. Some persons reduced or interrupted commercial sex work during the pandemic: 9 persons had 10 or fewer partners during the 3 months before the study.

When seen at the clinic, patients were diagnosed with various STIs (Table 3). None of the STIs were identified more frequently in patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 result. Ten percent had previously known HIV infection, and only 1 patient was diagnosed with HIV during the study. Syphilis was detected in 6% and required treatment.

Diagnoses of Venereal Infections During the Study Period.

| Overall | Negative SARS-CoV-2 result | Positive SARS-CoV-2 result | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 512 | 388 | 124 | |

| HIV serology, No. (%) | 0.32 | |||

| Not performed | 47 (9.2) | 34 (8.8) | 13 (10.5) | |

| Negative | 410 (80.1) | 313 (80.7) | 97 (78.2) | |

| Positive (new diagnosis) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Previous positive result | 54 (10.5) | 41 (10.6) | 13 (10.5) | |

| Syphilis serology, No. (%) | 0.371 | |||

| Primary | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Secondary | 8 (1.7) | 4 (1.1) | 4 (3.6) | |

| Early latent | 16 (3.4) | 11 (3.1) | 5 (4.5) | |

| Late latent | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Treated (serological scar) | 76 (16.3) | 60 (16.9) | 16 (14.4) | |

| Negative | 360 (77.4) | 274 (77.4) | 86 (77.5) | |

| Hepatitis A virus serology testing, No. (%) | 0.535 | |||

| Not performed | 375 (73.2) | 279 (71.9) | 96 (77.4) | |

| Immune | 63 (12.3) | 48 (12.4) | 15 (12.1) | |

| Negative | 68 (13.3) | 56 (14.4) | 12 (9.7) | |

| Previously vaccinated | 6 (1.2) | 5 (1.3) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Hepatitis B virus serology testing, No. (%) | 0.531 | |||

| Not performed | 433 (84.6) | 325 (83.8) | 108 (87.1) | |

| Negative | 42 (8.2) | 35 (9.0) | 7 (5.6) | |

| Previously infected | 5 (1.0) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Vaccinated | 32 (6.2) | 25 (6.4) | 7 (5.6) | |

| Hepatitis C virus serology testing, No. (%) | 103 (20.2) | 82 (21.1) | 21 (17.1) | 0.396 |

| Herpes simplex virus serology testing, No. (%) | 0.85 | |||

| Not performed | 496 (96.9) | 376 (96.9) | 120 (96.8) | |

| IgG positive for type 1 HSV | 5 (1.0) | 4 (1.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| IgG positive for type 2 HSV | 4 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | |

| IgG positive for types 1 and 2 HSV | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Negative | 5 (1.0) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (1.6) | |

Abbreviation: HSV, herpes simplex virus.

The number of sexual partners was not normally distributed and could not be normalized using logarithms; therefore, it was expressed as the median (2 sexual partners in the previous 3 months). The multivariate analysis showed that having more than the median number of sexual partners was associated with a positive SARS-CoV-2 result (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.13–2.88) with respect to patients who had the median or fewer partners. The use of FFP2 masks acted as a protective factor (OR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.28–0.89).

A positive result or presence of compatible symptoms (probable cases) was associated with the number of sexual partners in the previous 3 months (OR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.32–3.01) and use of FFP2 masks (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.31–0.79).

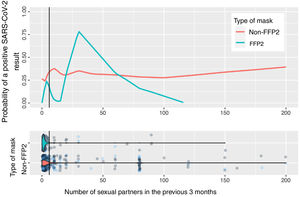

Fig. 2 shows the calculation based on locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) of the probability of a positive SARS-CoV-2 result with respect to the number of sexual partners and the type of mask used. The vertical line represents the 75th percentile (8 sexual partners); the estimation cannot be made at the tail of the distribution.

DiscussionThe overall estimated seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among persons with an STI or at risk of STI seen at our public dedicated clinic is high (24.2% during March–April 2021), and higher than that estimated in a study closest to ours in time both in the Autonomous Community of Madrid (18.6%; 95% CI, 16.7–20.6)16 and in Spain (9.9%; 95% CI, 9.4–10.4).17 The characteristics most associated with a positive test result were the use of non-FFP2 masks and a higher number of sexual partners.

The use of masks without a filter (i.e., not FFP2 or similar) doubled the risk of contagion, whereas more than the median number of sexual partners increased the risk by 80%. Use of an FFP2 mask differed between the groups in the sample: it was strikingly less frequent in a vulnerable group such as commercial sex workers, most of whom were non-European. No STIs were associated with a positive SARS-CoV-2 result.

In the estimation of the probability of contagion using LOWESS according to number of sexual partners and use of masks (Fig. 2), we can observe that the group of persons who used FFP2 masks and did not have sexual partners or had very few sexual partners had a low risk of contagion, unlike those who used non-FFP2 masks, among whom the risk was greater than 25%, even among persons with no sexual partners. The risk increases in persons who use FFP2 masks when there are more sexual partners than the median. When interpreting the graph, it is important to remember that number of sexual partners is a variable with an extraordinarily long tail to the right and a small number of persons who have a high number of sexual partners: in this area, the estimations of probability of contagion are unstable, and the information is more reliable on the left of the graph, where most patients lie. However, even in patients with a high number of sexual partners, we cannot observe a clear impact on the estimation of the probability of contagion.

Taken together, these observations reaffirm the role of the respiratory tract in contagion by SARS-CoV-2,1 given the effectiveness in prevention of face masks with a filter,18 which is more marked than the potential sexual route, even in sexually active persons.

Commercial sex work was not directly associated with a positive SARS-CoV-2 result, although it was associated with the number of sexual partners and the use of masks without filters, which were costly at the time of the study. Therefore, we agree with other authors that commercial sex workers should be considered a population at risk of coronavirus.11

During the study period, we recorded a total of 178 diagnoses of STI, some of which were concomitant in the same person. This is consistent with the global increase in STIs currently observed in Spain19 and with the return to prepandemic incidence levels.20,21 While another study found an association between the increase in the number of cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a tertiary hospital in Valencia and the decrease in the incidence of STI,22 data from the present study do not allow us to confirm this observation.

Our study has a series of strengths, for example, a sample that was sufficiently large to address the first objective of the study, consistency in the data collected by dermatologists with a subspecialty in venereal disease, and the demographic diversity of the population. The main limitation is the impossibility of completely separating social variables that may have been confounders and, therefore, determining the impact of each of them.

ConclusionsA positive SARS-CoV-2 result was more frequent in the sexually active population than in the general population. According to the data, the main route of contagion in this group is the respiratory tract. Therefore, sexual transmission seems to be very limited and is probably associated with the close contact inherent to sexual relations.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with respect to the present article.

We are grateful to the nurses and nursing assistants of our department, whose excellent work is essential for the care of the patients attending the clinic.

We are also grateful to David Lora Pablos for his advice on statistics.