Whenever we talk of the Olavide Museum and its wax models, the first person we remember is José Enrique Zofio Dávila (1835–1915), who created 80% of the models still in existence. The second we remember is José Barta Bernardota (1875–1955), who produced nearly all the other figures we have. The last of the sculptors, Rafael López Álvarez (1898–1987), worked on few of the moulages. His main importance lay in cataloging and packing the collection before it was lost.1

Rafael López Álvarez (Fig. 1) was born on September 20, 1898, in Madrid. We know about his life in part thanks to information provided by his great nephew, who helped the museum gather information. Although we know he was born a legitimate child of named parents — the museum holds his birth certificate — we also have among our holdings a diploma issued by Madrid’s children’s hospice† certifying that his skill in creating models was excellent. The diploma was dated July 12, 1918, when he was 20 years old, around the time he began to work at the Olavide Museum. José Barta was already the director then, and López Álvarez’s arrival might have coincided with the final years of Enrique Zofio’s work. In the 1940s, after José Barta’s retirement, López Álvarez took over as head of the Olavide Museum, which was then located in Hospital San Juan de Dios on Calle de Dr Esquerdo. The museum was in evident decline by that time and was only visited by students and a few groups interested in culture.

One of López Álvarez’s duties during the Spanish Civil War was showing the figures to members of the militias so that they could see the damage caused by venereal diseases. He was a picturesque character, who was described in various 1978 newspaper interviews as “rational, republican, and an admirer of Ferrer Guàrdia,”2 the late 19th-century anarchist and educator who was executed by firing squad in 1903. López Álvarez recounted stories about the museum, and his interviewers even named him as the creator of some of the figures. One anecdote he told concerned the model of a child — a girl or a boy — with tinea favosa. A man who had made his fortune in Spain’s former American colonies had made attempts to purchase it, claiming that the moulage represented him when he was a patient in Hospital San Juan de Dios.3 However, on finding the case history for this patient in the museum’s archives, we saw it was done in 1881, well before the man’s birth in 1888.4 Furthermore, the patient in the model was a girl.

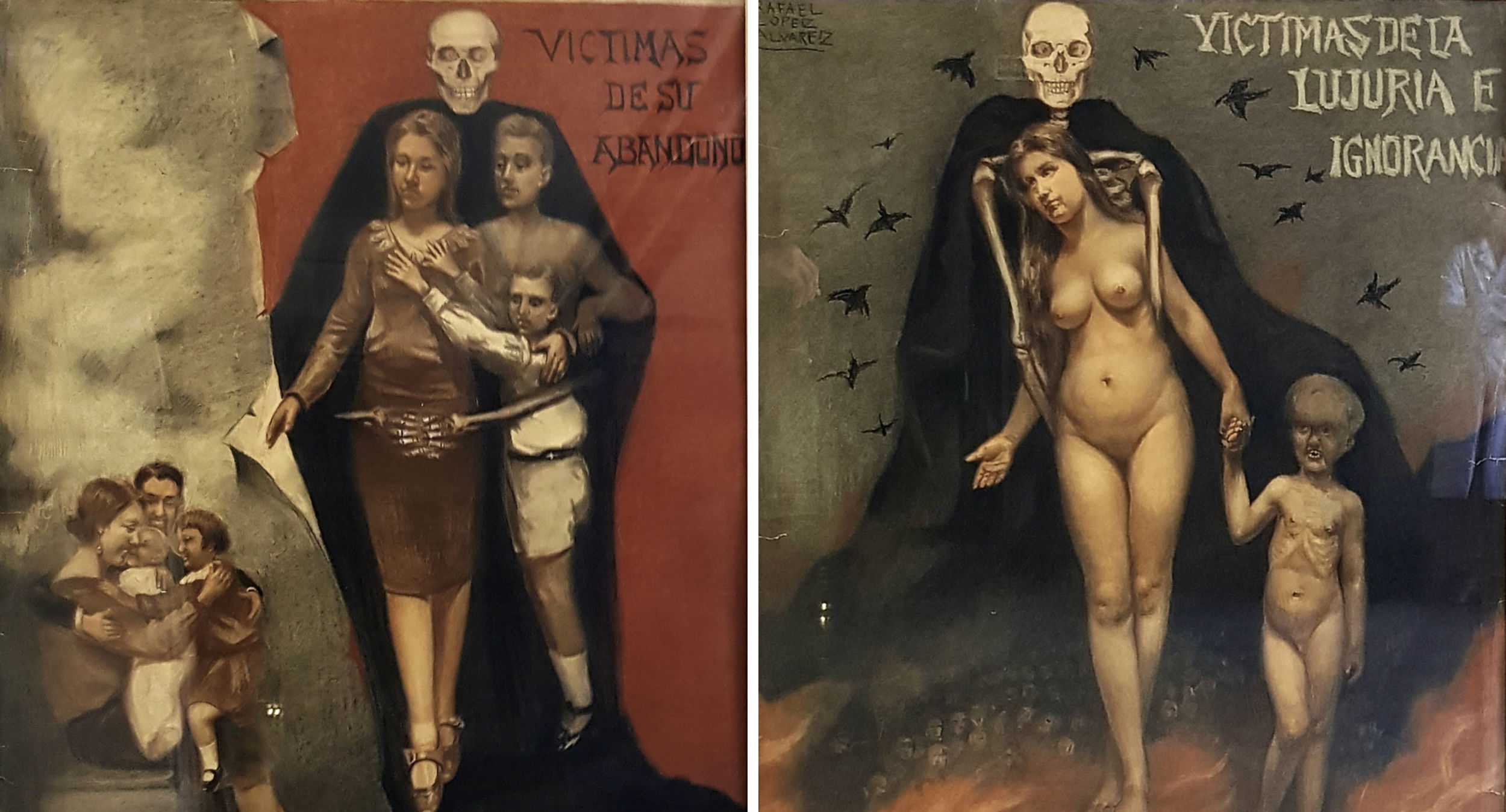

According to López Álvarez’s relatives, he was a painter of some skill, especially adept at portraits of women. His family donated a series of his oil paintings and water colors to the museum, where they remain in our archives. In one of the previously cited interviews,2 he also described posters he had designed for campaigns to prevent venereal diseases. One of them had even been proscribed as immoral during the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. Two original copies of his posters on the subjects of syphilis and gonorrhea (Fig. 2) have been acquired by the museum and are now on display, along with posters by Ramon Casas i Carbó (1886–1932). They are of historical interest, illustrating the moralistic approach to these diseases at the time they were printed.

López Álvarez lost his sight after an operation for glaucoma in 1972, but we have further knowledge of him in 1978, through an article in the magazine Qué, which mentions his work in the Olavide Museum.2

He suffered economic difficulties in the final years of his life, according to his family, who recalled that he was assigned a place in a residence thanks to his friendship with Joaquín Leguina, president of the autonomous community of Madrid. He never actually went there to live, however. His paintings were given to the community of Madrid and are presently stored in the Reina Sofía National Museum of Art according to our source.

López Álvarez, who was married to Isabel Rodríguez Valero, died on July 31, 1987, and was laid to rest in Madrid’s Almudena cemetery on August 1 of that year. His great contribution was cataloging and boxing the museum’s collection of wax models toward the end of 1966,3 just before Hospital San Juan de Dios was closed and razed, to be replaced by the current Hospital Gregorio Marañón (formerly known as the Residencia Francisco Franco).

We believe that although López Álvarez did not sculpt many figures and he had a certain tendency to tell tall tales, he kept us from losing one of the finest existing collections of wax moulages. As a result, the Olavide Museum can place them at the service of both dermatologists and the community thanks to the inestimable help of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV).

Please cite this article as: Conde-Salazar L. Rafael López Álvarez. El último cero-escultor del Museo Olavide. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:293–294.

Translator’s note: The shelter is called the “Hospicio de Madrid” in the original Spanish version of this article. It was certainly the one whose full name was the Real Hospicio del Ave María y San Fernando, now the city’s history museum.