Notalgia paresthetica is a sensory mononeuropathy that affects dorsal segments T2 to T6. It can have a significant effect on quality of life. Numerous treatments have been used with variable results.

Material and methodsFive patients diagnosed with notalgia paresthetica were treated with intradermal botulinum toxin A. None had achieved relief of the pruritus with previous treatments.

ResultsVariable results were observed after the administration of intradermal botulinum toxin. Complete resolution of the pruritus was not achieved in any of the patients.

ConclusionsBotulinum toxin A appears to be a safe therapeutic option for patients with notalgia paresthetica. However, data currently available come from small patient series, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions regarding the true efficacy and long-term effects of this treatment.

La notalgia parestésica es una mononeuropatía sensitiva que afecta a los segmentos dorsales T2 a T6 y puede alterar significativamente la calidad de vida de los pacientes. Para su tratamiento se han empleado diversas alternativas con resultados muy variables.

Materiales y métodosSe trataron 5 pacientes diagnosticados de notalgia parestésica con toxina botulínica A intradérmica. Ninguno de los tratamientos que todos ellos habían recibido previamente había logrado controlar su prurito.

ResultadosLos resultados observados tras la administración de toxina botulínica intradérmica fueron variables. En ninguno de los pacientes tratados se consiguió la resolución completa del prurito.

ConclusionesLa toxina botulínica tipo A parece ser una alternativa terapéutica segura para los pacientes con notalgia parestésica. Sin embargo, los datos disponibles hasta la fecha proceden de series de pacientes pequeñas, lo que dificulta la extracción de conclusiones definitivas acerca de la eficacia real y los efectos a largo plazo de este tratamiento.

Notalgia paresthetica (NP) is considered a sensory mononeuropathy of unknown origin that presents with localized pruritus in dorsal segments T2 to T6.1,2 Other symptoms include pain, paresthesia, hypo- and/or hyperesthesia, and burning. NP is frequently associated with a brownish patch in the affected area.

Nerve impingement is thought to be the chief cause, although other factors have been suggested as potential causes or triggers.2–5

Various topical and systemic treatments6–14 have been found to achieve partial or complete remission of symptoms for variable periods of time, but long-term results are discouraging in most cases. In 2007, Weinfeld reported a satisfactory response to botulinum toxin (BTX) in 2 patients with NP.15 Subsequently, Wallengren and Bartosik16 reported variable improvement of pruritus in 4 patients with NP.

Five patients with NP diagnosed in our department were treated with intradermal BTX. We describe our observations 1, 6, 12, and 18 months after treatment. This is the longest follow-up period reported to date.

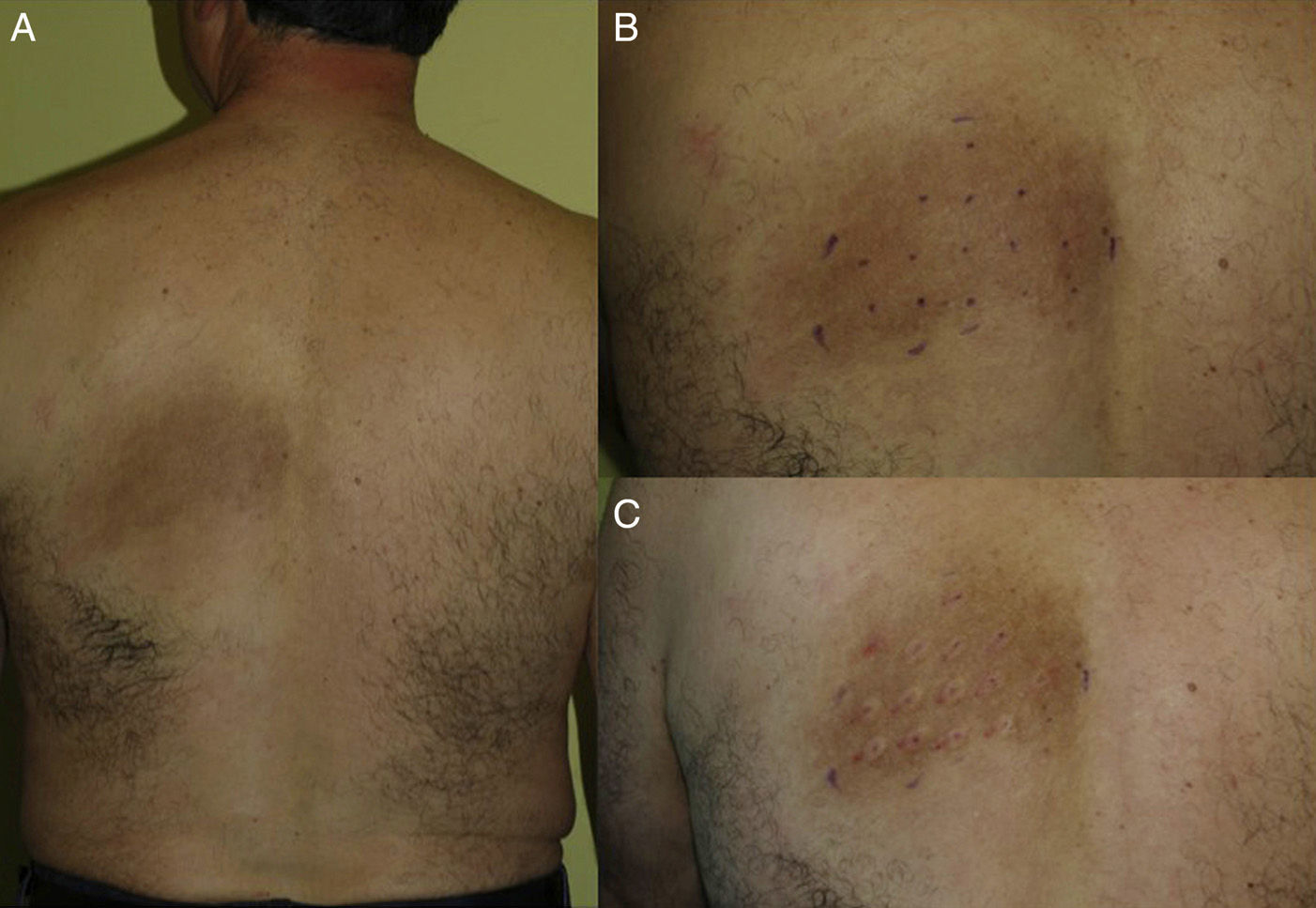

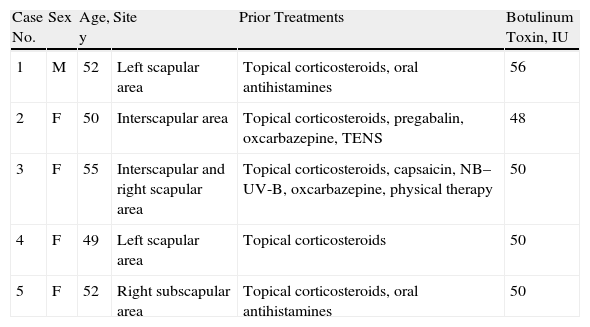

Material and MethodsWe included 5 consecutive patients (4 women, aged 49–55 years; 1 man, age 52 years) diagnosed with NP and monitored in our department since 2009. All patients had a highly pruriginous hyperpigmented patch on their backs (Fig. 1) and reported significant interference with daily life. Patient 2 also experienced pain in the affected area. All patients had previously received other topical and systemic treatments with no improvement (Table 1).

Clinical Features, Prior Treatments, and Amounts of BTX Administered in Each Case.

| Case No. | Sex | Age, y | Site | Prior Treatments | Botulinum Toxin, IU |

| 1 | M | 52 | Left scapular area | Topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines | 56 |

| 2 | F | 50 | Interscapular area | Topical corticosteroids, pregabalin, oxcarbazepine, TENS | 48 |

| 3 | F | 55 | Interscapular and right scapular area | Topical corticosteroids, capsaicin, NB–UV-B, oxcarbazepine, physical therapy | 50 |

| 4 | F | 49 | Left scapular area | Topical corticosteroids | 50 |

| 5 | F | 52 | Right subscapular area | Topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines | 50 |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; NB–UV-B, narrowband ultraviolet-B phototherapy; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Patients were treated with intradermal injections of BTX type A (BTX-A), specifically onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox, Allergan S.A.U, Madrid, Spain), according to the method described by Weinfeld.15 The treatment area was first marked on the basis of clinical appearance, and the injection points were set 2cm apart (Fig. 1, B and C). Prior to injection, a eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA cream, AstraZeneca Farmacéutica España S.A., Madrid, Spain) was placed on the area and left under occlusion for 1.5 hours. Every vial of BTX-A was reconstituted with 2.5mL of normal saline (0.9%) and an insulin syringe was then used to inject 4 units (0.1mL) at each injection point. The size of the affected area determined the total dose received by each patient (Table 1).

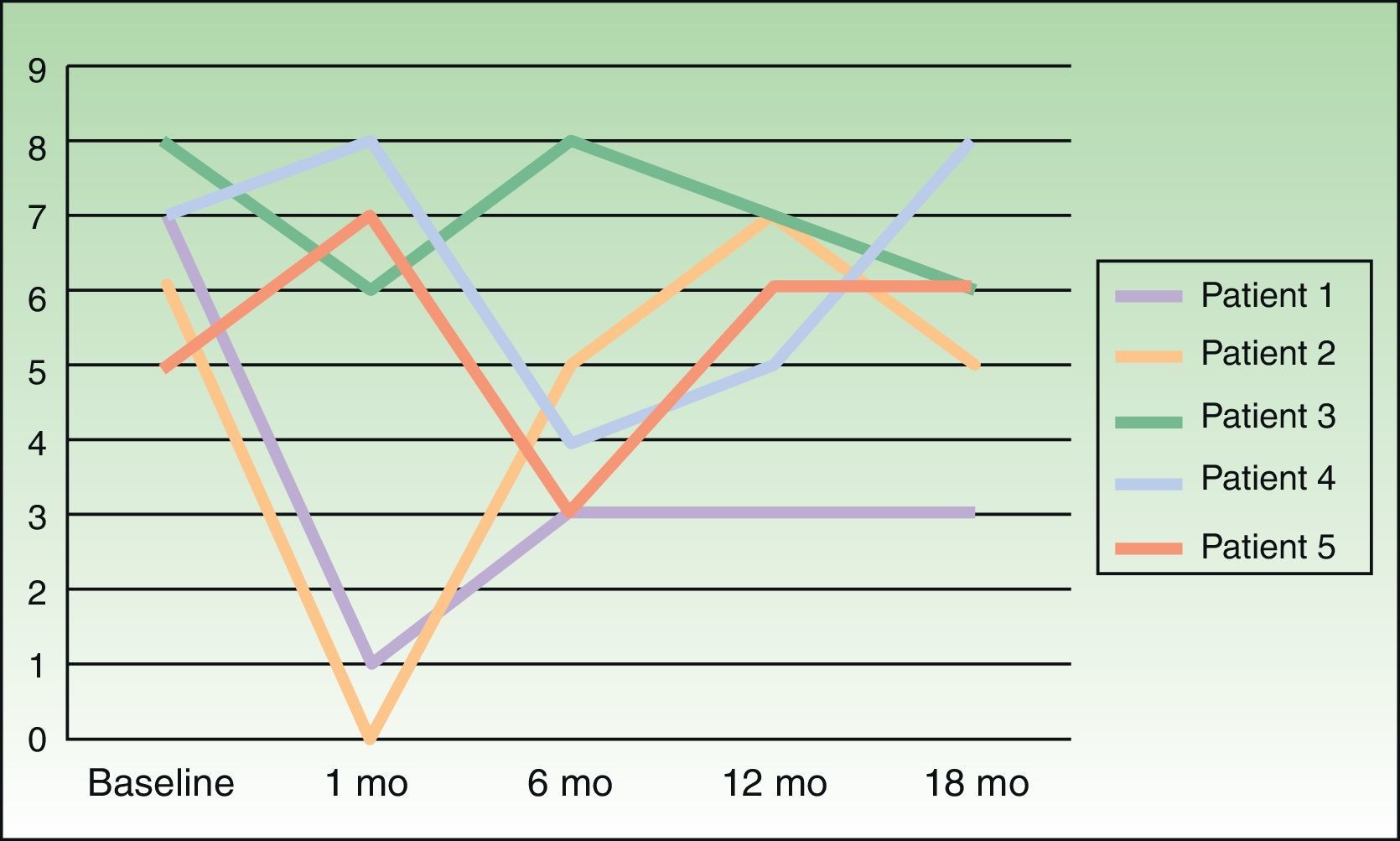

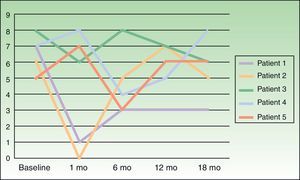

Severity of itching was assessed on a visual scale numbered from 0 to 10, at baseline and 1, 6, 12, and 18 months following treatment.

ResultsOutcomes varied widely, as shown by the changes in pruritus (Fig. 2). No changes in size or color of the hyperpigmented patch were observed in any of the patients.

No immediate or delayed adverse effects were recorded. Treatment was well tolerated by all patients. Pain experienced during the procedure was scored between 1 and 2 on a visual scale of 0 to 10.

DiscussionBTX-A is a neurotoxin that inhibits the release of substance P, norepinephrine, and glutamate; stimulates the release of calcitonin gene–related peptide; and attenuates histamine-induced pruritus.15,16

Weinfeld15 proposed BTX-A as an effective treatment for NP after using it successfully on 2 patients. The author reported complete resolution of pruritus in 1 patient for at least 18 months following a single treatment, and complete resolution in the other patient within a week of her second treatment.

We attempted to replicate these results in a larger number of patients, although we restricted treatment to a single course of BTX-A per patient. Our results were markedly different from Weinfeld's. First, pruritus failed to disappear completely in any of our patients. Shortly after treatment, 3 of our 5 patients reported improvement, but this response never lasted longer than 1 month. Interestingly, the other 2 patients even experienced worsening pruritus. Wallengren and Bartosik17 used BTX to treat 4 patients with NP, 1 patient with meralgia paresthetica, and 1 patient with neuropathic pruritus on the dorsum of the foot. BTX was administered in amounts ranging from 0.8 to 1.5 IU at injection points spaced 1.5 cm apart. The outcomes they observed also varied widely, consistent with our observations, although their patients were only followed for 6 weeks. One of their NP patients reported being completely itch-free 6 weeks after treatment, but the others experienced improvement for 1 to 10 days following treatment and itching worsened again after that period. Despite these variable outcomes and the fact that most treated patients failed to achieve complete remission of itching, the authors of this study judged BTX a useful alternative for treating this condition.

Our study clearly has limitations. We only quantified a single subjective symptom (pruritus) based on the patient's own assessment on a pain scale. We did not evaluate the potential influence of factors other than the drug itself (for instance, mechanical stimulation, tissue distention, or even a placebo effect), and we had no control group for comparison.

NP is typically a chronic condition with a variable course that may include periods of seemingly spontaneous improvement; mid- to long-term response to treatment is therefore difficult to assess.

Our findings as well as those of Wallengren and Barstik17 suggest that BTX is of doubtful use in treating NP. Our long follow-up period enabled us to note that response to treatment varies from patient to patient as well as over time. Nevertheless, we view BTX as a potentially useful and safe treatment for patients with NP who have failed to improve with other forms of therapy. A good initial response to BTX could be used to select patients who might potentially benefit from regular treatment.

Currently we have no evidence to suggest that BTX is more effective than other options for treating NP. In order to clearly establish the benefits of this treatment and to define a treatment protocol for this subset of patients, further research is needed, including randomized placebo-controlled trials such as one currently under way,18 as well as larger-scale trials comparing its effectiveness to that of other treatments.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed their health care centers’ protocols on the publication of data concerning patients and that all patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Pérez L, García-Gavín J, Allegue F, Caeiro J, Fabeiro J, Zulaica A. Tratamiento de la notalgia parestésica con toxina botulínica A intradérmica. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:74–77.