Between 29% and 53% of the patients who develop basal cell carcinoma (BCC) will develop new BCCs.

ObjectivesCurrent objectives are to analyze the proportion and basic characteristics of patients who develop BCC >1, to delineate the concept of multiple BCC (mBCC) and be able to identify the factors associated with its development, and analyze its timeframe.

Patients and methodWe conducted a retrospective observational study including all patients diagnosed with sporadic BCC from January 1st, 2014 through December 31st, 2014 at a tertiary referral center. Data included dates of BCCs, gender, age and histology of the first BCC, and the presence of BCC >1 at the initial appointment (cluster+). mBCC was defined as a patient who developed a series of BCCs >the 75th percentile of the series.

ResultsA total of 758 patients (51.2% men), were included. After a median follow-up of 100 months, 52.8% of the patients developed BCC >1. The 75th percentile of the number of BCCs was 3. Factors associated to mBCCs included being cluster+ (OR, 5.6; 95%CI, 3.2–9.7), being men (OR, 3.1; 95%CI, 2.0–4.8) and diagnosed with the first BCC between ages of 50 and 80 years (OR, 2.1; 95%CI, 1.3–3.5). After 5 years, 54% of patients exhibiting these three factors developed mBCC. The estimated median time to mBCC was 38.00 months (95%CI, 0–79.71).

ConclusionsA quarter of patients who exhibit 1 BCC eventually develop four or more BCCs. Analyzing routine parameters may help identify individuals at a higher risk of developing mBCC and predict its timeframe.

Entre el 29%-53% de los pacientes que desarrolla un carcinoma basocelular (CBC), desarrolla nuevos CBC.

ObjetivosAnalizar la proporción y características básicas de los pacientes que desarrollan> 1 CBC; perfilar el concepto de CBC múltiple (CBCm); identificar factores asociados a su desarrollo y analizar su patocronia.

Pacientes y métodoSe diseñó un estudio retrospectivo observacional incluyendo a todos los pacientes diagnosticados de CBC esporádico entre el 1 de enero del 2014 y el 31 de diciembre del 2014 en un hospital terciario. Se registraron: fechas de cada CBC, sexo, edad y patrón de riesgo del primer CBC y existencia de> 1 CBC en el primer contacto (clúster+). Se definió como CBCm aquel caso que desarrollara un número de CBC superior al P75 de la serie.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 758 pacientes (51,2% varones). El seguimiento (mediana) fue 100 meses. El 52,8% de los pacientes desarrolló> 1 CBC. El P75 del número de CBC fue 3. Ser clúster+ (OR=5,6; IC del 95%, 3,2-9,7), varón (OR=3,1; IC del 95%, 2,0-4,8) y ser diagnosticado del 1.° CBC entre los 50-80 años (OR=2,1; IC del 95%, 1,3-3,5) son factores independientes para CBCm. A los 5 años de seguimiento, el 54% de los pacientes con estos 3factores desarrolló CBCm. La mediana estimada para ello fue 38,00 meses (IC del 95%, 0-79,71).

ConclusionesEl 25% de los pacientes que presenta un CBC, desarrolla 4 o más de ellos. El análisis de factores disponibles en la práctica clínica diaria permite estimar quiénes tienen mayor riesgo de hacerlo y el tiempo en el que lo desarrollarán.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) accounts for 75% of malignant skin neoplasms.1 Australia, with an incidence of 1600 per 100,000 per year, is the region with the highest incidence of BCC worldwide. The current trend in tumor diagnosis is increasing in regions such as Europe, Asia, and South America, with an annual increase of 5% over the past 10 years. In Spain, the estimated crude global incidence rate of BCC is 113.05 per 100,000 people/year.2

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation plays a key role in the development of BCC, especially intense and intermittent sun exposure during the early years of life.3 Exposure to UVB induces mutations in tumor suppressor genes, while UVA radiation induces mutations through the generation of reactive oxygen species. Photosensitizing drugs increase the skin's vulnerability to UV-induced damage.4 UV produces mutations in the PTCH1 gene, which activates the hedgehog pathway. This cellular pathway stimulates cell proliferation, and its activation is pathogenic in the development of BCC.3 Other exogenous influencing factors include ionizing radiation, arsenic, and immunosuppression. Immunosuppression in organ transplant recipients multiplies the probability of developing a BCC by a factor of 10. These findings have also been reported in patients who are HIV-positive.3 Phenotypically, BCC is more common in patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes I–II, light eye color, freckles, and blond or red hair.3 Exceptionally, BCC develops in the context of genetic disorders that predispose to BCC; Gorlin syndrome is probably the best known.1,3 However, in most cases, BCCs are sporadic, and up to 29–53% of patients develop >1 BCC.3,5–8

The main risk factor for the development of BCC is sun exposure.1,3,9 However, the factors involved in the development of subsequent BCCs are less well defined.4,10 Having developed a BCC is a risk factor for developing new BCCs.11,12 This risk can be as much as 17 times higher than in the population who have not developed BCC.4 Early age at diagnosis13 of the first BCC, the superficial pattern of the tumor,10,14 presenting with >1 BCC at the first patient visit (cluster+),10,15 male sex,16–18 place of residence,11 and being red-haired13 have been proposed as predisposing factors. As for the location of the first tumor,13–15,19 contradictory results have been published, but in g.20 Certain polymorphisms in different genes (glutathione S-transferase, cytochrome P450, vitamin D receptor gene, etc.) may facilitate the growth of further BCCs.1

The present study aims to: (1) analyze the proportion and basic epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients who develop >1 BCC; (2) define the concept of multiple BCC (mBCC); (3) identify basic factors associated with the development of mBCC; and (4) establish the timeline with which mBCC develops.

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective observational study in the health care area of a tertiary referral center, including all patients diagnosed with BCC from January 1st, 2014 through December 31st, 2014, excluding cases with <6-month follow-up and those diagnosed with genodermatoses predisposing to skin neoplasms. mBCC was defined as any patient with a number of BCCs >75th percentile of the series. The following variables were collected: sex at birth, date of birth, date of each BCC developed, initial and simultaneous diagnosis of several BCCs, date of last contact, and WHO risk pattern of the first BCC diagnosed.21

Continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U statistic. Nominal variables were compared using chi-squared statistics. Pearson's test was used for correlations. Variables with p<0.01 in the univariate analysis were entered as potential explanatory factors for the development of mBCC in a binary logistic regression model. Survival was estimated by Kaplan–Meier curves and mortality tables. Curves were compared using the log-rank test, and for multivariate analysis, the Cox proportional hazards model was applied. For all tests, the significance level was set at p≤0.05. Calculations were performed using SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The project was approved by the local CEIm (CHUNSC_2023_29). As this was a retrospective study, we did not have data that undoubtedly influence the development of BCC (location, pigmentary phenotype, history of severe actinic burns, sun exposure, etc.).

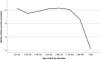

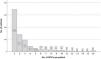

ResultsA total of 758 of the 771 patients diagnosed with BCCmet the inclusion criteria. Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the series. The median follow-up was 100.0 months (IQR, 92.0–108.0 months). This was shorter in those whose first BCC was diagnosed at advanced ages (rho=−0.241(756), p<0.001) (Fig. 1). A total of 400 (52.8%) patients developed >1 BCC. Fig. 2 illustrates the number of patients according to the number of BCCs diagnosed. The median number of BCCs developed per patient was 2.00 (IQR, 1.00–3.00). At the first patient visit, a single BCC (cluster− patients) was diagnosed in 673 patients (88.8%). In 85 patients (11.2%), >1 BCC was diagnosed at the first visit (cluster+ patients): 2 in 72 cases (9.5%), and 3 in 13 patients (1.7%). The median number of BCCs later diagnosed in the cluster+ group was 2.0 (IQR, 0.5–6.0), and in the cluster− group, 0.0 (Mann–Whitney U; p<0.001). The median total number of BCCs diagnosed in the cluster+ group was 5.0 (IQR, 3.0–8.0), and in the cluster− group, 1.0 (IQR, 1.0–3.0) (Mann–Whitney U; p<0.001).

Global characteristics of the series and by number of basal cell carcinomas developed.

| N (%) | Total758 (100) | 1 BCC358 (47.2) | 1 BCC400 (52.8) | p-Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.942d | |||

| Median | 68.7 | 68.6 | 68.7 | |

| IQR | 58.9–77.1 | 58.3–78.4 | 58.4–78.4 | |

| Gender | 0.008a | |||

| Male | 388 (51.2) | 165 (42.5) | 223 (55.8) | |

| Female | 370 (48.8) | 193 (57.5) | 177 (44.2) | |

| Risk patternc | 0.094 | |||

| High risk | 181 (28.2) | 87 (25.4) | 96 (31.4) | |

| Low risk | 465 (71.8) | 255 (74.6) | 210 (68.6) | |

BCC: basal cell carcinoma; IQR: interquartile range; Age: age at diagnosis of the first BCC.

The 75th percentile (P75) for the number of BCCs per patient was 3.00. Therefore, those who developed >3 BCCs were considered cases of multiple BCC (mBCC) (175 patients). Table 2 shows the characteristics of patients with mBCC and the results of the univariate analysis. The multivariate analysis (Table 3) showed that the risk of developing mBCC is independently increased: (1) in cluster+ patients (OR, 5.6; 95%CI, 3.2–9.7) (p<0.001); (2) in men (OR, 3.1; 95%CI, 2.0–4.8); (3) if the first BCC is diagnosed between the ages 50 and 80 years (OR, 2.1; 95%CI, 1.3–3.5). The WHO risk pattern of the first BCC diagnosed did not influence this risk.

Univariate analysis of possible predictive variables for developing multiple BCCs (more than three basal cell carcinomas).

| Variable | Univariate analysis | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple basal cell carcinoma | ||||

| No | Yes | Total | ||

| Age 50–80 years,cN (%) | <0.001a | |||

| Yes | 381 (72.4) | 145 (27.6) | 526 (100) | |

| No | 202 (87.1) | 30 (12.9) | 232 (100) | |

| Male,bN (%) | <0.001a | |||

| Yes | 274 (70.6) | 114 (29.4) | 388 (100) | |

| No | 309 (83.5) | 61 (16.5) | 370 (100) | |

| Risk pattern,eN (%) | 0.077a | |||

| Low | 383 (82.4) | 82 (17.6) | 465 (100) | |

| High | 139 (76.0) | 44 (24.0) | 183 (100) | |

| Cluster,dN (%) | <0.001a | |||

| Yes | 36 (42.4) | 49 (57.6) | 85 (100) | |

| No | 547 (76.9) | 175 (23.1) | 758 (100) | |

Multivariate analysis of selected predictive variables for developing multiple BCCs (>3 basal cell carcinomas).

| Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic regression | ||||

| OR | 95%CI (lower) | 95%CI (upper) | p | |

| Malea | 3.1 | 2.0 | 4.8 | <0.001 |

| Age 50–80 yearsb | 2.1 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 0.004 |

| Cluster+c | 5.6 | 3.2 | 9.7 | <0.001 |

| Riskd | 1.4 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 0.110 |

| Cox regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI (lower) | 95%CI (upper) | p | |

| Malea | 2.0 | 1.4 | 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Age 50–80 yearsb | 2.0 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 0.002 |

| Cluster+c | 4.8 | 3.4 | 6.7 | <0.001 |

| Riskd | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.626 |

HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

The estimated overall median time to develop mBCC was 178.0 months (95%CI, 151.4–204.6). Table 4 illustrates the estimated medians for each variable. The multivariate analysis (Table 3) confirms that being male (HR, 2.0; 95%CI, 1.4–2.7), cluster+ (HR, 4.8; 95%CI, 3.4–6.8), or diagnosed with the first BCC between the ages 50 and 80 years (HR, 1.9; 95%CI, 1.3–2.9) independently increase the risk of developing mBCC. At the 5-year follow-up, 13% of patients had developed mBCC. Except for risk pattern, the figures differ significantly according to the variables analyzed (Table 5).

Univariate analysis of the interval to develop multiple BCCs (>3 basal cell carcinomas).

| Median (months) | 95%CI (lower) | 95%CI (upper) | pe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malea | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 141.0 | 107.3 | 174.7 | |

| No | 220.0 | 173.8 | 204.6 | |

| Age 50–80 yearsb | 0.002 | |||

| Yes | 175.0 | 139.0 | 211.0 | |

| No | NR | NR | NR | |

| Cluster+c | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 71.0 | 50.4 | 91.5 | |

| No | 200.0 | 174.5 | 225.5 | |

| Riskd | 0.79 | |||

| High | 200.0 | 175.4 | 224.6 | |

| Low | 167.0 | 136.6 | 198.4 | |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; NR: median not reached.

Percentage of patients who develop multiple BCCs (>3 basal cell carcinomas).

| Follow-up (years) | Global | Riska,e | Sex at birthf | Clusterb,g | Aged (years)h | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (%) | High (%) | Female | Male | Negativec | Positiveb | 50–80 | Other | ||

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 16 | 6 | 4 |

| 3 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 35 | 9 | 6 |

| 4 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 7 | 14 | 7 | 40 | 11 | 9 |

| 5 | 13 | 12 | 14 | 8 | 18 | 9 | 43 | 14 | 10 |

| 6 | 15 | 14 | 17 | 9 | 20 | 10 | 51 | 16 | 10 |

| 7 | 18 | 17 | 21 | 12 | 24 | 13 | 55 | 21 | 11 |

| 8 | 21 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 27 | 17 | 57 | 24 | 13 |

| 9 | 23 | 21 | 27 | 16 | 30 | 18 | 57 | 25 | 16 |

| 10 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 22 | 32 | 22 | 65 | 29 | 21 |

| 11 | 59 | 66 | 48 | 48 | 68 | 55 | 95 | 64 | 38 |

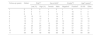

For patients without independent risk factors or with only one, the estimated median time to develop a 4th BCC was 220.00 months (95%CI, 182.8–257.2 months). In cases with two predictive factors, the estimated median was 167.00 months (95%CI, 122.5–211.5 months). In the group with all three predictive factors, the estimated median was 38.00 months (95%CI, 0–79.7 months) (log-rank; p<0.001) (Fig. 3). The rates of mBCC growth based on the number of risk factors present were 6%, 18%, and 54% at 5 years, depending on whether the patient had 1 or 0, 2, or all 3 risk factors, respectively. In the latter group, at 11 years, virtually all grow mBCC (Wilcoxon test; p<0.001) (Table 6).

Probability of developing multiple basal cell carcinoma (>3 BCCs [mBCC]) based on the number of significant and independent predictive factors at diagnosis of the first basal cell carcinoma: (1) male sex, (2) simultaneous diagnosis of >1 basal cell carcinoma at the patient's first visit, and (3) age at diagnosis of the first basal cell carcinoma between 50 and 80 years.

Percentage of patients who develop multiple basal cell carcinoma based on the number of risk factors.

| Follow-up (years) | Low riska | Moderate riskb | High riskc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 22 |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | 35 |

| 3 | 4 | 8 | 41 |

| 4 | 5 | 13 | 54 |

| 5 | 6 | 18 | 54 |

| 6 | 7 | 20 | 62 |

| 7 | 9 | 26 | 65 |

| 8 | 12 | 29 | 65 |

| 9 | 13 | 31 | 65 |

| 10 | 18 | 33 | 72 |

| 11 | 45 | 69 | 99.96 |

Risk group definitions:

Focusing on sporadic BCCs, a meta-analysis describes the development of >1 BCC in 29% of patients.5 However, other studies suggest that this rate reaches 39.9–52.7% at the 5-year follow-up.3,6–8,11 A total of 400 of the 758 patients included in the present study (52.8%) grew >1 BCC at the 10-year follow-up. The literature usually refers to mBCC when a patient has >1 BCC.22 In contrast, in the present study, mBCC is defined as a patient who grows several BCCs >P75; therefore, >3 BCCs. We considered P75 to be a practical criterion as it segregates a 25% subgroup of patients who likely have distinctive characteristics, susceptible to future studies, and who may benefit from optimized intervention protocols.

Old age is associated with a higher risk of additional BCCs,6,11,17,22 with up to an 80% risk increase in patients diagnosed between ages 65 and 79.17 In the present study, 27.6% of patients aged 50–80 years grew mBCC; only 12.9% of patients of other ages did so (p<0.001). The multivariate analysis showed that being diagnosed with the first BCC in this age range is an independent factor for mBCC (OR, 2.1) (Table 3). Beyond the age of 80, the incidence of new BCCs in our patients decreased (Fig. 2). This finding is consistent with that published by Verkouteren et al.,10 who suggest that risk increases with age but decreases after age 68. This finding could be related to difficulties in patient follow-up10 (Fig. 1). As far as we know, only 1 study specifies the risk for developing >3 BCCs based on age. In it, patients diagnosed with their first BCC after age 60 have a 4.2-fold greater risk of growing >3 BCCs vs those diagnosed before age 40.16 These findings closely match those observed in the present and other series4,6

Most studies associate male sex with a higher risk of developing >1 BCC.6,11,16–18,22 The estimated risk increase is 30% (HR, 1.3; 95%CI, 1.1–1.5).12 A total of 65% of our patients with mBCC were male (p<0.001). This figure is similar to the 60% reported for patients with >3 BCCs.13 Our analysis demonstrated that being male multiplies the risk of developing mBCC by approximately 3, being an independent predictive factor. In the only study we know where sex is studied for patients with >3 BCCs, the OR was 1.8 (95%CI, 1.1–3.2).16 In most studies, adjustment was not made for histological subtype and location. Without such adjustments, the risk for males is multiplied by 1.3 (95%CI, 1.1–1.5).17 If these variables are adjusted for, no association is identified between sex and the tendency to develop >1 BCC.10 However, male sex becomes more predominant in subgroups with a higher number of BCCs,11,22 with an OR, 1.8 (95%CI, 1.1–3.2) for growing 2–3 BCCs and OR, 2.8 (95%CI, 1.5–5.3) for developing >3 BCCs.16 This last figure is consistent with that observed in our male patients, who had an OR of 3.0 (95%CI, 1.9–4.8) for growing mBCC.

The subtype of the first BCC diagnosed has been associated with the development of further BCCs,10,13,14 mainly the superficial pattern, especially when combined with location on the trunk.14 For this combination, a 3.32-fold greater risk of developing >1 BCC vs other combinations has been reported. In this study, we grouped BCC histological patterns according to their risk per WHO classification.21 In agreement with former studies,9 the minority of patients (28.2%) showed a high-risk pattern21 in the first BCC, yet we did not detect significant differences for patients with mBCC (Table 2).

It is not uncommon that, at the time of diagnosis of the first BCC, the patient presents with >1 of these tumors (cluster+). In our series, 11.2% of patients were cluster+, very similar to published rates, which usually range from 1210 to 13%.23 Cluster+ status is a predictive factor for the development of new NMSC, increasing the risk by 22–43%,23 and is considered10 the predictive factor with the greatest weight (OR, 2.5) for developing >1 BCC. Our analysis confirms this finding, multiplying the probability of developing mBCC by 5.6 (Table 3).

Cluster+ status is also the variable that most strongly differentiates the rate of mBCC development (Table 5). At the 5-year follow-up, 43% of cluster+ patients and 8% of cluster− patients developed mBCC. The median time to develop mBCC is significantly lower in cluster+ (71 months) vs cluster− patients (200 months). The multivariate analysis shows that sex (HR, 2.0), diagnosis of the index case between 50 and 80 years (HR, 2.0), and cluster+ status (HR, 4.8) are independent predictors of the interval to develop mBCC (Table 3). There is a significant difference in the median interval to mBCC among patients with 0–1 of these factors (220 months), 2 factors (167 months), and all 3 factors (38 months) (Fig. 3). A prognostic rule has been proposed10 that includes four of the variables analyzed in this study among its five items. In that study, patients with the maximum score have a 40% risk of growing a second BCC at 5 years. Unfortunately, this rule does not apply as a function of the number of tumors, so a direct comparison with our study cannot be drawn. However, in our series, 54% of patients with all independent predictive factors grew mBCC at the 5-year mark (Table 6).

The present study was based on the review of routine health records, so it is possible that a targeted examination would have identified a greater number of cluster+ patients. Additionally, there are factors (phenotypes, UV exposure, immunosuppression, etc.) that could potentially be related to the number of BCCs developed and that were not included in this analysis.

The increasing incidence of NMSC24 represents a significant burden for health systems.25 It demands a high number of medical consultations and numerous surgical resources. Having information to identify individuals prone to developing multiple BCCs, as well as on the chronology of their appearance, would allow for optimization of care for this patient group and the use of available resources.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

![Probability of developing multiple basal cell carcinoma (>3 BCCs [mBCC]) based on the number of significant and independent predictive factors at diagnosis of the first basal cell carcinoma: (1) male sex, (2) simultaneous diagnosis of >1 basal cell carcinoma at the patient Probability of developing multiple basal cell carcinoma (>3 BCCs [mBCC]) based on the number of significant and independent predictive factors at diagnosis of the first basal cell carcinoma: (1) male sex, (2) simultaneous diagnosis of >1 basal cell carcinoma at the patient](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/00017310/0000011600000008/v1_202509020454/S0001731025004557/v1_202509020454/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr3.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w9/t1/zx4Q/XH5Tma1a/6fSs=)