An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is a harmful and unintended response to drugs administered in therapeutic doses. Among these, cutaneous adverse reactions (CARs) are one of the most frequent clinical forms, which may occasionally be severe (SCARs).

ObjectivesTo describe the epidemiology of SCARs managed in a pediatric hospital.

MethodsA retrospective observational study of patients under 18 years of age who presented with a SCARs between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2022. Exclusion criteria: immunosuppression, IgE-mediated allergic reactions, incomplete data, and no need for hospitalization.

ResultsOf the 2433 patients diagnosed with a CAR, 34 (1.4%) presented with a SCAR. The main drugs involved were antibiotics, followed by NSAIDs and anticonvulsants. In 97.1% of cases (33 patients), the reason for prescribing the medications was an acute pathology. The final diagnoses were as follows: severe maculopapular rash in 21 patients, DRESS syndrome in 6, generalized exanthematous pustulosis in 3, erythema multiforme in 2, Stevens–Johnson syndrome in 1 and toxic epidermal necrolysis in 1. Two patients (5.9%) had a poor outcome. No deaths were reported in this series.

ConclusionSCARs are very rare in pediatrics with a predominance of severe maculopapular rash. Clinical outcomes are generally favorable, although approximately 5% may present acute complications or sequelae, some of which may be severe. Therefore, upon initial suspicion of any of these SCARs, the potentially causal drugs should be immediately discontinued.

.

An adverse drug reaction (ADR), according to the World Health Organization (WHO), is a harmful and unintended response to a medication administered at therapeutic doses.1 The incidence of ADRs in children is difficult to determine because pre-marketing clinical trials include a limited number of pediatric patients, preventing an accurate estimate of the true incidence; moreover, these trials are generally not conducted in the pediatric population.2

Risk factors for developing an ADR include female sex, immunosuppression, and certain genetic haplotypes. Children whose parents have a confirmed drug allergy have a 15-fold higher relative risk of experiencing allergic reactions to the same drugs.3

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions (CADRs), also known as drug-induced toxicoderma, are among the most common clinical signs. They account for approximately 35% of all ADRs in children, second only to GI ADRs (39%).4 It is estimated that 2.5% of children treated with any medication, and up to 12% of those receiving an antimicrobial, will develop a CADR.5 In a 10-year pediatric ADR registry published by Damien et al. in 2016, 21.1% of all ADRs were CADRs, and of these, 38.7% were caused by antimicrobials.2

In children, CADRs present a diagnostic challenge because they can mimic much more common conditions—particularly viral infections, Kawasaki disease, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4 Some CADRs may be severe (sCADRs), requiring hospitalization and potentially resulting in complications and/or sequelae.6 Classically recognized sCADRs include drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP).3 In recent years, however, terminology has begun to change. Ramien et al.7 proposed the term drug-induced epidermal necrolysis (DEN) to describe the SJS/TEN spectrum of drug-related disease. These entities are clinically important because of their significant morbidity and notable mortality rates: approximately 10% for DRESS, 1–5% for SJS, 25–30% for TEN, and <5% for AGEP.8 They also carry a high risk of severe complications or permanent sequelae.

The aim of this study was to describe the epidemiology of sCADRs managed at a Spanish pediatric hospital.

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective observational study including patients younger than 18 years diagnosed with an sCADR at a tertiary-care Spanish pediatric hospital between January 1st, 2011, and December 31st, 2022.

sCADRs were defined as cases requiring hospitalization with a final diagnosis of DRESS, EM, AGEP, TEN, or SJS during the study period. Patients with immunosuppression, IgE-mediated allergic reactions, or incomplete data were excluded.

Clinical and sociodemographic variables were collected, including age, sex, past medical history (previous allergies, atopic dermatitis, chronic diseases), family history of drug allergy, implicated or potentially implicated sCADRs, indication for prescription, start and stop dates, date of symptom onset, pediatric assessment triangle (PAT) findings, fever, physical examination findings (respiratory distress, gastrointestinal symptoms, joint involvement, visceromegaly, and description and extent of cutaneous lesions), laboratory and imaging results, performance of skin biopsy and/or allergy testing, final diagnosis, treatment administered, hospitalization characteristics, and criteria for poor outcome.

Definitions of the outcomes of interest and other key concepts are shown in Table 1.

Definitions of outcomes of interest and other definitions.

| Name | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Outcomes of interest | |

| Severe cutaneous adverse drug reaction (sCADR) | Dermatosis affecting the skin, mucous membranes, and adnexa caused by the harmful effects of medications (regardless of the route of administration),9 capable of causing significant disability10 or life-threatening complications, and requiring hospital admission. |

| Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome) | Drug-induced reaction with a long latency between exposure and onset of disease (diagnostic criteria according to J-SCAR [Japanese Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reaction] and RegiSCAR [European Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions] are shown in the supplementary data).10,11 |

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) (<10% body surface area detachment) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) (>30% body surface area detachment) | Severe cutaneous reactions, generally medication-induced, characterized by extensive epidermal necrosis and detachment, with mucosal involvement in 90% of cases.11 |

| Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) | Severe type IV hypersensitivity cutaneous reaction related to viral and bacterial infections and, less frequently, to drugs (mainly antibiotics).8 |

| Severe maculopapular exanthem (SME) | Erythematous maculopapular eruptions spreading in a cephalocaudal pattern between 4 days and 3 weeks after initiation of the drug; may be associated with pruritus, low-grade fever, and, rarely, non-ulcerative mucosal involvement.3 |

| Other definitions | |

| Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT) | Tool used to assess the initial general impression of a child.12 |

| Hemodynamic instability | Tachycardia with heart rate>2 SD above age norms and/or hypotension defined as systolic blood pressure<2 SD below age norms.13 |

| Hemodynamic support treatment | ≥1 bolus of normal saline 10mL/kg or initiation of inotropic infusion. |

| Poor outcome criteria | Acute complications, sequelae, and/or death. |

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA v.17 (StataCorp). Qualitative variables are expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages; quantitative variables as mean, median, and ranges. The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee (reference R-0023/22).

Primary clinical outcome variables were the frequencies of each sCADR diagnosis: DRESS, SJS, TEN, AGEP, and SME.

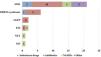

ResultsDuring the study period, a total of 2433 patients were evaluated in the emergency department for a CADR, of whom 34 (1.4%) were diagnosed with an sCADR. Seventeen (50.0%) were male, and the median age was 8.6 years (interquartile range [IQR] 5.3–11.3). Implicated drugs by sCADR type, personal history, and epidemiologic characteristics are shown in Tables 2 and 3, and their relationship with the final diagnosis in Fig. 1.

Epidemiological characteristics, medical history, and implicated drugs.

| sCADR N=34 | |

|---|---|

| Male sex, N (%) | 17 (50) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 8.6 (5.3–11.3) |

| History of allergy, N (%) | 7 (20.6) |

| Sensitization to aeroallergens | 3 (8.8) |

| CMPA | 3 (8.8) |

| Drugsa | 1 (2.9) |

| History of atopic dermatitis, N (%) | 3 (8.8) |

| Previous diseases, N (%) | 15 (44.1) |

| Asthma | 3 (8.8) |

| Epilepsy | 3 (8.8) |

| Eating behavior disorderb | 2 (5.9) |

| Hematologic diseasesc | 2 (5.9) |

| Congenital syndromesd | 2 (5.9) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1 (2.9) |

| Sensorineural hearing loss | 1 (2.9) |

| Cerebellar cyste | 1 (2.9) |

| Family history of CADRf | 2 (5.9) |

| Drugs implicated in CADR | |

| Antibiotics, N (%) | 19 (55.9) |

| β-Lactams | 15 (44.1) |

| Cephalosporins | 8 (23.5) |

| Cefotaxime | 7 (20.6) |

| Ceftriaxone | 1 (2.9) |

| Penicillins | 6 (17.6) |

| Amoxicillin | 5 (14.7) |

| Cloxacillin | 1 (2.9) |

| Carbapenems | 1 (2.9) |

| Non-β-lactams | 5 (14.7) |

| Glycopeptides (Vancomycin)g | 2 (5.9) |

| Quinolones | 1 (2.9) |

| Sulfonamides | 1 (2.9) |

| Nitroimidazoles | 1 (2.9) |

| NSAIDs, N (%) | 6 (17.6) |

| Ibuprofen | 4 (11.7) |

| Metamizole | 2 (5.9) |

| AEDs, N (%) | 4 (11.8) |

| Lamotrigine | 2 (5.9) |

| Phenytoin | 1 (2.9) |

| Oxcarbazepine | 1 (2.9) |

| Others, N (%) | 5 (14.7) |

| Magnesium sulfate | 1 (2.9) |

| Gabapentin | 1 (2.9) |

| Rituximab | 1 (2.9) |

| Immunoglobulins | 1 (2.9) |

| Plasmapheresis | 1 (2.9) |

CMPA, cow's milk protein allergy; CADR, cutaneous adverse drug reaction; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; AEDs, antiepileptic drugs.

Personal history and epidemiological characteristics by type of severe cutaneous adverse drug reaction.

| SMEN=21 | DRESSN=6 | AGEPN=3 | EMN=2 | SJSN=1 | TENN=1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex, N (%) | 13 (62) | 3 (50) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50) | 1 (100) | 0 |

| Age (years), M (IQR) | 9.3 (1–16.4) | 7.6 (5.7–8.6) | 8.7 (3–12.8) | 9.8 (8.8–10.8) | 12 | 5 |

| Prior diseases, N (%) | 11 (52.4) | 4 (66.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| History of allergy, N (%) | 6 (28.6) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Time from drug start to symptoms (days), M (range) | 0 (0–13) | 19.5 (9–28) | 5 (0–8) | 3.5 (0–7) | 4 | 1 |

| Drug withdrawal, N (%) | 16 (76.2) | 6 (100) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Time to drug withdrawal (days), M (range) | 0.5 (0–21) | 0.5 (0–5) | 5 (2–7) | 6.5 (3–10) | 0 | 1 |

M, median; IQR, interquartile range; SME, severe maculopapular eruption; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; EM, erythema multiforme; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome.

The median time from drug initiation to symptom onset was 1 day (range 0–28), and the median time from symptom onset to drug withdrawal was 3 days (range 0–27).

In 97.1% (33/34), the drug was prescribed for an acute condition, usually infectious—most commonly ENT infections (6 cases, 17.6%) and pneumonia (3 cases, 8.8%)—or represented the recent introduction of a new drug for a chronic disease (e.g., change in antiepileptic drug (AED) due to poor seizure control).

General clinical signs and cutaneous findings are summarized in Table 4.

General clinical characteristics and cutaneous findings by type of severe cutaneous adverse drug reaction.

| SMEN=21 | DRESSN=6 | AGEPN=3 | EMN=2 | SJSN=1 | TENN=1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Abnormal PAT, N (%) | 4 (19) | 4 (66.7) | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 | 0 |

| Fever, N (%) | 3 (14.3) | 5 (83.3) | 0 | 2 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Hemodynamic instability, N (%) | 4 (19) | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (50) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Respiratory distress, N (%) | 3 (14.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| GI symptoms, N (%) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia/arthritis, N (%) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Visceromegaly, N (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cutaneous involvement | ||||||

| Generalized maculopapular exanthem, N (%) | 21 (100) | 6 (100) | 0 | 2 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Vesicles/bullae, N (%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (100) | 1 (50) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Petechiae, N (%) | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Mucosal/conjunctival involvement, N (%) | 5 (23.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Edema, N (%) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (50) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

PAT, Pediatric Assessment Triangle; SME, severe maculopapular eruption; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; EM, erythema multiforme; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome.

The implicated drug was discontinued in 29 patients (85.3%). Additional test results are shown in Table 5.

Additional tests and abnormal analytical values by final diagnosis.

| SMEN=21 | DRESSN=6 | AGEPN=3 | EMN=2 | SJSN=1 | TENN=1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood test, N (%) | 9 (42.9) | 6 (100) | NA | 2 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Anemia (<11g/dL) | 2 (9.5) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Thrombocytopenia (<150,000/mm3) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) | NA | 1 (100) | |

| Leukopenia/Leukocytosis (4500–10,000/mm3) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) | NA | NA | |

| Eosinophilia (>500/mm3) | NA | 3 (50) | NA | |||

| Hyponatremia (<135mEq/L) | NA | |||||

| Elevated AST (>50U/L) | NA | 4 (66.7) | 1 (50.0) | |||

| Elevated ALT (>45U/L) | NA | 4 (66.7) | 1 (50.0) | |||

| Elevated GGT (>50U/L) | NA | 2 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) | |||

| Elevated LDH (>200) | NA | 4 (66.7) | NA | |||

| Urinalysis, N (%) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Skin biopsy, N (%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Abdominal ultrasound, N (%) | 2 (9.5) | 4 (66.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Allergy tests, N (%) | 14 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Positive allergy test | 9a (64.3) | 3b (100) | – | – | – | – |

ND, not available; SME, severe maculopapular eruption; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; EM, erythema multiforme; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; NA, not available.

Final diagnoses were SME in 21 patients (61.8%), DRESS in 6 (17.6%) (Fig. 2), AGEP in 3 (8.8%) (Fig. 3), EM in 2 (5.9%), SJS in 1 (2.9%), and TEN in 1 (2.9%) (Fig. 4).

All cases required hospitalization or were hospitalized because of the sCADR. Hospital course, treatments, and outcomes are described in Table 6. A total of 15 patients (44.1%) received treatment. In 9 cases (26.5%)—5 EMPG, 3 AGEP, and 1 DRESS—management was symptomatic (antihistamines and/or corticosteroids). Six children (17.6%) required supportive therapy due to poor clinical progression (3 allergic/hypersensitivity reactions; 1 SJS; 1 EM; 1 TEN). Among these: 4 (66.7%) required crystalloid resuscitation with normal saline for hemodynamic instability (3 drug-induced hypersensitivity reactions, and the SJS case), and 2 (33.3%) required PICU admission (1 EM and 1 TEN, both caused by ibuprofen). The 2 PICU cases developed acute respiratory distress syndrome; one required invasive mechanical ventilation. They also developed secondary wound infections requiring surgical debridement and IV antibiotics. Both experienced sequelae: one developed functional impairment of the right lower limb due to extensive scarring, and the other required enucleation of the left eye due to repeated bacterial and fungal infections in the PICU. No sCADRs-induced deaths occurred in this series (Supplementary data).

Hospitalization characteristics, treatment received, and outcomes of severe cutaneous drug reactions.

| SMPEN=21 | DRESSN=6 | AGEPN=3 | EMN=2 | SJSN=1 | TENN=1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay (days), Median (IQR) | 6 (0–91) | 10.5 (4–61) | 0 | 19 (11–27) | 15 | 65 |

| PICU admission, No. (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Received any treatmenta, No. (%) | 8 (23.5) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) |

| Symptomatic treatment | ||||||

| Antihistamines | 5 (62.5) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Corticosteroids | 3 (37.5) | 1 (100) | 3 (100) | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Supportive treatment | ||||||

| IV fluid expansion (normal saline) | 3 (37.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Vasoactive drugs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Intubation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Complications, No. (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Sequelae, No. (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Death, No. (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

M, median; IQR, interquartile range; SMPE, severe maculopapular exanthema; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; EM, erythema multiforme; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit.

sCADRs are uncommon in pediatric patients, yet they must be considered in the differential diagnosis of any child receiving pharmacologic therapy who develops cutaneous signs. These reactions may occur both in previously healthy children and in those with underlying chronic disease. Antibiotics—predominantly β-lactams—were the most common culprit drugs in the former group, whereas aromatic AEDs predominated in the latter.

Although the literature typically describes infants and preschool-aged children younger than 6 years as the most frequently affected,14 the mean age in our cohort was higher. This likely reflects the fact that our center manages patients up to 18 years of age, whereas many pediatric hospitals limit care to children younger than 14–16 years.

Consistent with former pediatric studies,15,16 antibiotics—particularly β-lactams—were the leading cause of sCADRs, most often triggering hypersensitivity reactions. This may be related to their widespread use during childhood.17 NSAIDs constituted the 2nd most common drug class associated with sCADRs. Although pediatric data are limited, Gomes et al.18 identified NSAIDs as the primary cause of cutaneous drug eruptions, including fixed drug eruptions, photosensitivity reactions, and sCADRs, and noted that they were among the medications most frequently associated with SJS in children. Aromatic AEDs (carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, and phenytoin), which are commonly used as first-line agents in pediatric epilepsy,19 represented the 3rd major category of culprit drugs.

Most patients in our study exhibited cutaneous findings consistent with a type IV hypersensitivity reaction. As described by Wilkinson et al.,20 these reactions commonly present with cutaneous involvement because the skin acts as an important reservoir of T lymphocytes. With the exception of AGEP, the remaining cases could likely be categorized within the DEN spectrum described by Ramien et al.21

In one of the largest pediatric series published to date (58 patients), Dibek Misirlioglu et al.22 reported a latency period of 7–21 days between drug exposure and onset of symptoms—a pattern also observed in our cohort.23

Regarding clinical features, 50% of patients with reactions within the DEN spectrum exhibited an abnormal pediatric assessment triangle upon arrival to the emergency department. Hemodynamic instability, a key marker of severity, was consistently present in cases of SJS and TEN but was also observed in hypersensitivity reactions, DRESS, and EM. In contrast, patients with AGEP exhibited the least systemic involvement. The most common initial cutaneous signs were maculopapular and urticarial exanthems with centrifugal spread, which could rapidly evolve into progressive erythema and epidermal detachment.18,21

Laboratory testing was the primary complementary evaluation and proved useful for assessing potential visceral involvement and sCADR severity. Similar to findings reported by Dibek Misirlioglu et al.,22 hepatic involvement was most frequent (60–80%), consistent with our results.

Norton et al.24 noted that <10% of antibiotic-related reactions are confirmed through allergy testing. In our cohort, allergy testing was performed in half of the patients—all with DRESS—and only 3 (<10%) had a positive lymphocyte transformation test. Given the test's high false-negative rate,25 underdiagnosis remains a concern.

Management of pediatric sCADRs remains challenging, and the limited literature emphasizes the need for rapid recognition, prompt discontinuation of the culprit drug, and timely initiation of appropriate treatment. Although no consensus exists, immediate withdrawal of the offending agent22—performed in 85% of our cases—remains the cornerstone of therapy. Systemic corticosteroids were the most frequently used treatment, in line with former studies that highlight their role alongside suspected drug withdrawal.4,22

Mortality rates for SJS and TEN are lower in children (approximately 7.5%) than in adults (25%); however, morbidity remains substantial.26 No deaths occurred in our cohort, although complications were more frequent than previously reported (20% vs approximately 1.7% in a 58-patient series),22 which may reflect our center's status as a tertiary referral hospital, receiving more complex cases from lower-level facilities.

ConclusionssCADRs are very rare in pediatric populations, with EM-like presentations being the most frequent in our cohort. They may occur in otherwise healthy, nonallergic children—most often triggered by antibiotics or NSAIDs—or in children with neurologic disease requiring aromatic AEDs. Although clinical outcomes are generally favorable, approximately 20% of patients may develop acute complications requiring pediatric intensive care unit admission, and some may experience serious long-term sequelae. Therefore, when an sCADR is suspected, all potentially causative medications should be discontinued immediately.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.