Predominantly sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and infestations and other anogenital dermatoses are covered in the training of specialists in dermatology and venereology in Spain. This study aimed to analyze the proportion of the dermatology caseload these diseases account for within the public and private dermatological activity of the Spanish health system.

Material and methodsObservational cross-sectional study of time periods describing the diagnoses made in outpatient dermatology clinics, obtained through the anonymous DIADERM survey of a representative random sample of dermatologists. Based on diagnostic codes of the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, 36 related diagnoses were selected, and classified into 12 groups.

ResultsOnly 3.16% of diagnoses corresponded to STIs and other anogenital dermatoses. The most common diagnostic group was anogenital human papillomavirus infection, followed by molluscum contagiosum, and inflammatory anogenital dermatoses. Lesions with these diagnoses were usually the main reasons for first visits in the National Health Service. In private practice, the diagnoses usually came after referrals from other physicians.

ConclusionsSTIs and other anogenital dermatoses account for a very small proportion of the dermatology caseload in Spain, although the inclusion of molluscum contagiosum diagnoses overestimates these conditions. The fact that no STI centers or monographic STI consultations were included in the random sample of dermatology partly explains the under-representation of these areas of the specialty. A determined effort to support and promote monographic STI centres and clinics should be made.

Las infecciones e infestaciones de transmisión predominantemente sexual y otras dermatosis anogenitales forman parte de la formación específica de los médicos especialistas en Dermatología y Venereología en España. El presente estudio pretende analizar la carga que suponen dichas patologías en la actividad dermatológica pública y privada del sistema de salud español.

Material y métodoEstudio observacional de corte transversal de dos períodos de tiempo describiendo los diagnósticos realizados en consultas externas dermatológicas, obtenidos a través de la encuesta anónima DIADERM, realizada a una muestra aleatoria y representativa de dermatólogos. A partir de la codificación de diagnósticos CIE-10, se seleccionó toda la patología relacionada (36 diagnósticos codificados en los dos períodos), que se clasificó en 12 grupos.

ResultadosTan solo el 3,16% de los diagnósticos globales fueron de infecciones e infestaciones de transmisión predominantemente sexual y otras dermatosis anogenitales. Los 3 grupos diagnósticos más frecuentes fueron las lesiones por virus del papiloma humano anogenital, seguido de los molluscum contagiosum y las dermatosis anogenitales inflamatorias. Con significación estadística, y comparando con el global de diagnósticos, los seleccionados constituyeron más habitualmente el motivo de consulta primario y, en el ámbito privado, fue más frecuente que viniesen derivados de otros especialistas.

ConclusiónLas infecciones e infestaciones de transmisión predominantemente sexual y otras dermatosis anogenitales tienen un peso muy limitado en la asistencia dermatológica en España, a pesar de que la inclusión del diagnóstico de molluscum contagiosum sobreestima estos diagnósticos. La ausencia de inclusión de centros y consultas monográficas de ITS en la muestra aleatoria contribuye a la infrarrepresentación de estas parcelas de la especialidad. Es importante hacer un esfuerzo decidido por potenciarlas con consultas y centros monográficos.

The goal of the DIADERM study was to analyze the diagnoses made in the medical-surgical dermatology and venereology (MSDV) clinics of the members of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología [AEDV]) in Spain1. The study included diagnoses of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and mucocutaneous anogenital disorders.

The incidence of STIs in Spain has continued to grow in recent decades. After the trough in incidence in 2001, with 2.04 confirmed gonococcal infections per 100 000 person-years, the number of cases reported has increased every year, reaching 24.18 per 100 000 person-years in 20182.

It is therefore essential to have an appropriate public health strategy to test, track, and treat cases of STI. Such a strategy requires the participation of specialists with specific training in the diagnosis and treatment of STIs. In this sense, MSDV is the only medical specialty in Spain whose name makes reference to this field of knowledge3, and, since, its earliest days, it has been closely associated with treatment of venereal diseases4. In general terms, dermatovenereologists have a clear role in the diagnosis and treatment of anogenital and mucosal skin conditions, especially vulvar diseases5.

The care provided to persons with or at risk of STIs varies between the health systems of the Spanish autonomous communities. Centers specialized in treating STIs continue to provide care (continuing the historical role of the Spanish antivenereal league centers 6), with significant participation from dermatologists, although some of these centers are currently at risk of being closed owing to lack of resources7. Similarly, some dermatology departments continue to run clinics for this subspecialty. However, in recent years, most care provided to patients with (or at risk of) STIs is through primary care and emergency departments. In this sense, while dermatologists play an active role in hospital emergency departments8, patients with STIs are not usually referred to them: the diseases account for a very low percentage of conditions managed in dermatology emergency departments (according to previous studies, <2% in Valladolid9 and <3% in Madrid10).

Based on the coded diagnoses resulting from the activity of dermatologists, we measured the demand by Spanish dermatologists for outpatient care of primarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations and other anogenital dermatoses. We also analyzed factors such as current differences in diagnoses according to geographic area and the origin and destination of the consultation according to whether the health care setting was public or private.

Materials and MethodsWe performed a cross-sectional observational study to describe the diagnoses made by dermatologists during 2 periods (January 19–21 and May 18–20, 2016). These data were obtained via the anonymous DIADERM survey, which was administered to a random sample of dermatologists stratified by sections of the AEDV and representative of dermatologists in Spain. The methodology and characteristics of the survey (including the data collected and the method used to code the diagnoses) are detailed in the first manuscript on the project1.

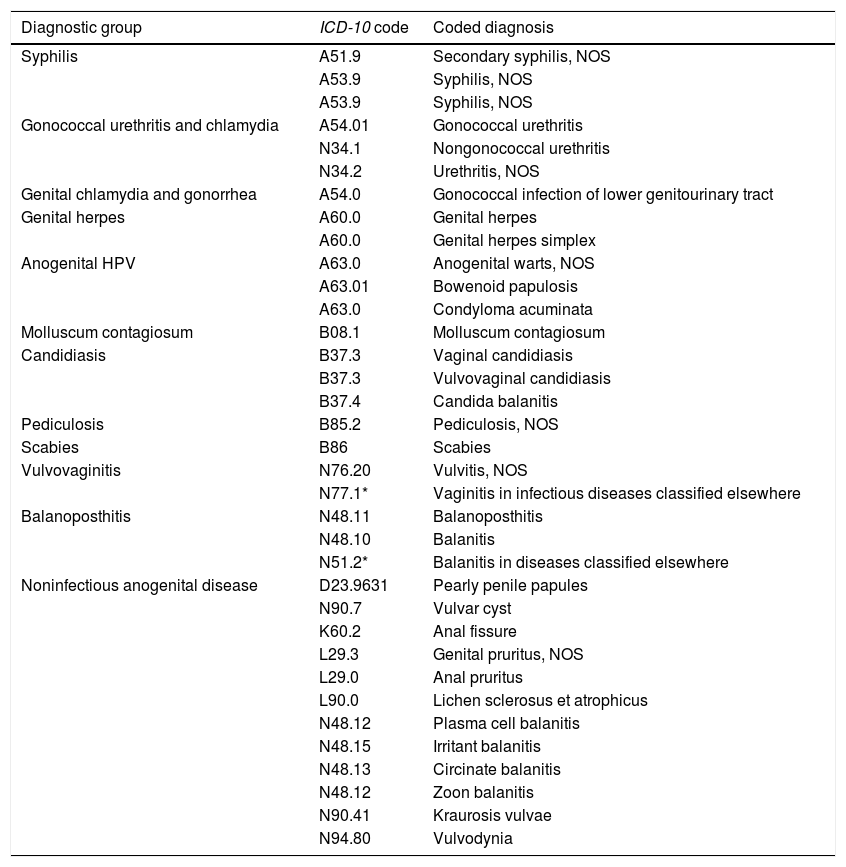

The specific analysis of primarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations and other anogenital dermatoses was based on a review made by one of the authors (AMG), who examined the complete list of coded diagnoses and selected 36 conditions (Table 1). This list was used to generate 12 diagnostic groups.

Diagnostic codes selected and groups.

| Diagnostic group | ICD-10 code | Coded diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Syphilis | A51.9 | Secondary syphilis, NOS |

| A53.9 | Syphilis, NOS | |

| A53.9 | Syphilis, NOS | |

| Gonococcal urethritis and chlamydia | A54.01 | Gonococcal urethritis |

| N34.1 | Nongonococcal urethritis | |

| N34.2 | Urethritis, NOS | |

| Genital chlamydia and gonorrhea | A54.0 | Gonococcal infection of lower genitourinary tract |

| Genital herpes | A60.0 | Genital herpes |

| A60.0 | Genital herpes simplex | |

| Anogenital HPV | A63.0 | Anogenital warts, NOS |

| A63.01 | Bowenoid papulosis | |

| A63.0 | Condyloma acuminata | |

| Molluscum contagiosum | B08.1 | Molluscum contagiosum |

| Candidiasis | B37.3 | Vaginal candidiasis |

| B37.3 | Vulvovaginal candidiasis | |

| B37.4 | Candida balanitis | |

| Pediculosis | B85.2 | Pediculosis, NOS |

| Scabies | B86 | Scabies |

| Vulvovaginitis | N76.20 | Vulvitis, NOS |

| N77.1* | Vaginitis in infectious diseases classified elsewhere | |

| Balanoposthitis | N48.11 | Balanoposthitis |

| N48.10 | Balanitis | |

| N51.2* | Balanitis in diseases classified elsewhere | |

| Noninfectious anogenital disease | D23.9631 | Pearly penile papules |

| N90.7 | Vulvar cyst | |

| K60.2 | Anal fissure | |

| L29.3 | Genital pruritus, NOS | |

| L29.0 | Anal pruritus | |

| L90.0 | Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus | |

| N48.12 | Plasma cell balanitis | |

| N48.15 | Irritant balanitis | |

| N48.13 | Circinate balanitis | |

| N48.12 | Zoon balanitis | |

| N90.41 | Kraurosis vulvae | |

| N94.80 | Vulvodynia |

Abbreviations: ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; NOS, not otherwise specified.

The variables collected for the first study were included.

The statistical analysis was performed by considering the design used to collect the sample and using the survey module of Stata11, which considers standard errors for correlated data. Furthermore, it was not necessary to correct the fit for finite populations, given that the real number of dermatologists for each section of the AEDV was close to 1.

The study was classified as a non–postauthorization study by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the province of Granada (October 8, 2014).

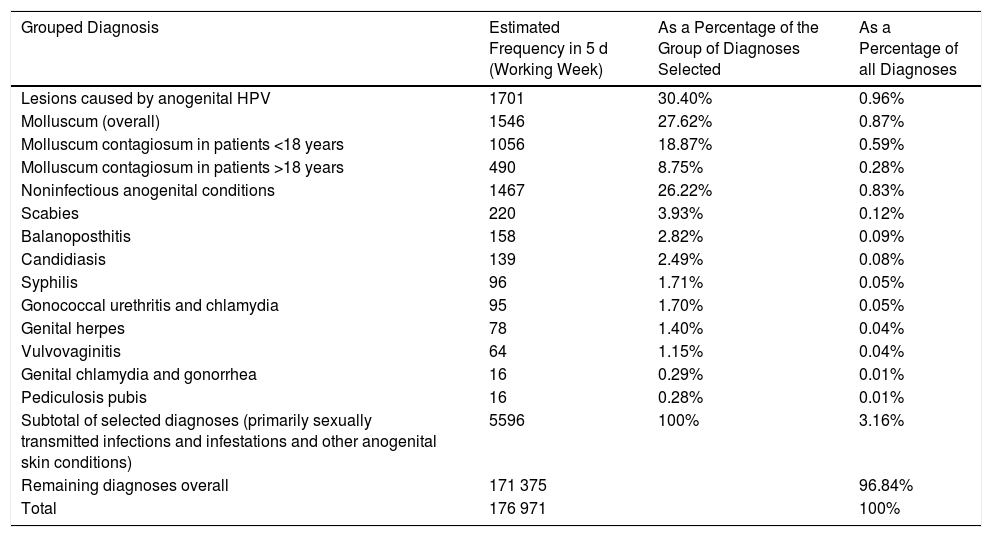

ResultsPrimarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations and other anogenital dermatoses accounted for 3.16% of the total number of diagnoses (5596 of 176 971 cases evaluated in a working week). Table 2 shows the population-based diagnoses by group in order of frequency. The 3 most common diagnostic groups were lesions caused by anogenital human papillomavirus (HPV), followed by molluscum contagiosum (of which 68.3% corresponded to patients aged <18 years) and noninfectious anogenital conditions.

Estimation of the frequency of selected diagnoses made throughout Spain by dermatologists in outpatient clinics.

| Grouped Diagnosis | Estimated Frequency in 5 d (Working Week) | As a Percentage of the Group of Diagnoses Selected | As a Percentage of all Diagnoses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesions caused by anogenital HPV | 1701 | 30.40% | 0.96% |

| Molluscum (overall) | 1546 | 27.62% | 0.87% |

| Molluscum contagiosum in patients <18 years | 1056 | 18.87% | 0.59% |

| Molluscum contagiosum in patients >18 years | 490 | 8.75% | 0.28% |

| Noninfectious anogenital conditions | 1467 | 26.22% | 0.83% |

| Scabies | 220 | 3.93% | 0.12% |

| Balanoposthitis | 158 | 2.82% | 0.09% |

| Candidiasis | 139 | 2.49% | 0.08% |

| Syphilis | 96 | 1.71% | 0.05% |

| Gonococcal urethritis and chlamydia | 95 | 1.70% | 0.05% |

| Genital herpes | 78 | 1.40% | 0.04% |

| Vulvovaginitis | 64 | 1.15% | 0.04% |

| Genital chlamydia and gonorrhea | 16 | 0.29% | 0.01% |

| Pediculosis pubis | 16 | 0.28% | 0.01% |

| Subtotal of selected diagnoses (primarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations and other anogenital skin conditions) | 5596 | 100% | 3.16% |

| Remaining diagnoses overall | 171 375 | 96.84% | |

| Total | 176 971 | 100% |

Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

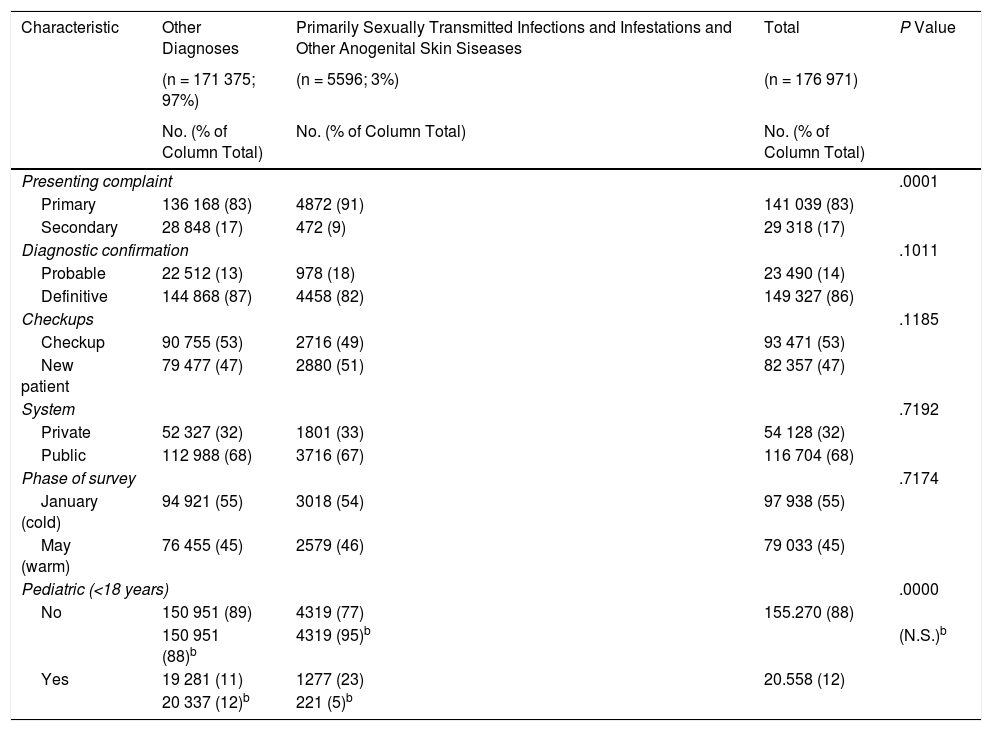

Table 3 shows the differences between the variables, taking into account the disease selected compared with the other diagnoses. The diagnoses selected were more commonly the main presenting complaint and were recorded more frequently in persons aged <18 years. This difference was statistically significant. However, this significant difference disappeared if cases of molluscum contagiosum in persons aged <18 years were excluded.

Characteristics of primarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations and other anogenital dermatoses (vs other diagnoses) in Spain.a.

| Characteristic | Other Diagnoses | Primarily Sexually Transmitted Infections and Infestations and Other Anogenital Skin Siseases | Total | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 171 375; 97%) | (n = 5596; 3%) | (n = 176 971) | ||

| No. (% of Column Total) | No. (% of Column Total) | No. (% of Column Total) | ||

| Presenting complaint | .0001 | |||

| Primary | 136 168 (83) | 4872 (91) | 141 039 (83) | |

| Secondary | 28 848 (17) | 472 (9) | 29 318 (17) | |

| Diagnostic confirmation | .1011 | |||

| Probable | 22 512 (13) | 978 (18) | 23 490 (14) | |

| Definitive | 144 868 (87) | 4458 (82) | 149 327 (86) | |

| Checkups | .1185 | |||

| Checkup | 90 755 (53) | 2716 (49) | 93 471 (53) | |

| New patient | 79 477 (47) | 2880 (51) | 82 357 (47) | |

| System | .7192 | |||

| Private | 52 327 (32) | 1801 (33) | 54 128 (32) | |

| Public | 112 988 (68) | 3716 (67) | 116 704 (68) | |

| Phase of survey | .7174 | |||

| January (cold) | 94 921 (55) | 3018 (54) | 97 938 (55) | |

| May (warm) | 76 455 (45) | 2579 (46) | 79 033 (45) | |

| Pediatric (<18 years) | .0000 | |||

| No | 150 951 (89) | 4319 (77) | 155.270 (88) | |

| 150 951 (88)b | 4319 (95)b | (N.S.)b | ||

| Yes | 19 281 (11) | 1277 (23) | 20.558 (12) | |

| 20 337 (12)b | 221 (5)b | |||

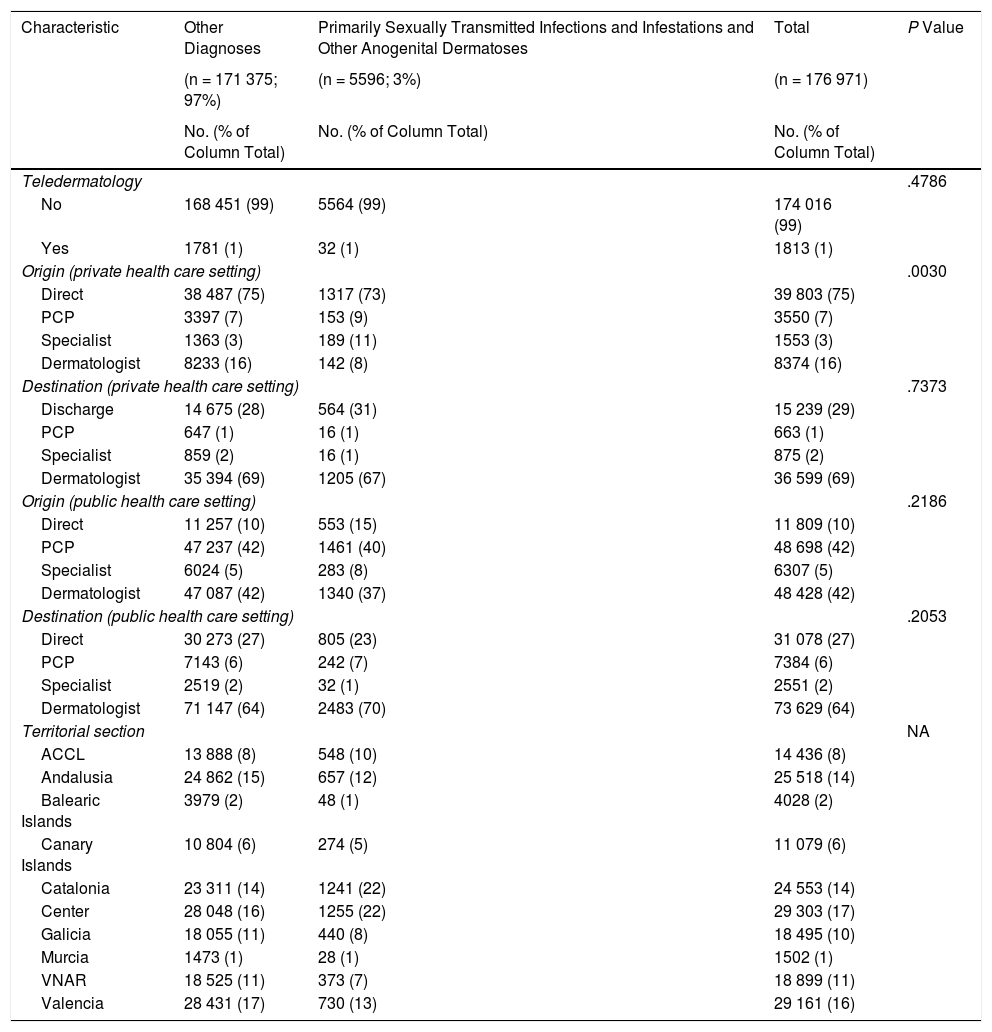

Table 4 shows the analysis of other variables. The only statistically significant differences found were for origin of the consultation in private clinics: compared with the remaining diagnoses, primarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations and other anogenital dermatoses were referred from other specialists.

Description of the administrative characteristics (care modality, origin, and destination) of primarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations and other anogenital dermatoses.a.

| Characteristic | Other Diagnoses | Primarily Sexually Transmitted Infections and Infestations and Other Anogenital Dermatoses | Total | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 171 375; 97%) | (n = 5596; 3%) | (n = 176 971) | ||

| No. (% of Column Total) | No. (% of Column Total) | No. (% of Column Total) | ||

| Teledermatology | .4786 | |||

| No | 168 451 (99) | 5564 (99) | 174 016 (99) | |

| Yes | 1781 (1) | 32 (1) | 1813 (1) | |

| Origin (private health care setting) | .0030 | |||

| Direct | 38 487 (75) | 1317 (73) | 39 803 (75) | |

| PCP | 3397 (7) | 153 (9) | 3550 (7) | |

| Specialist | 1363 (3) | 189 (11) | 1553 (3) | |

| Dermatologist | 8233 (16) | 142 (8) | 8374 (16) | |

| Destination (private health care setting) | .7373 | |||

| Discharge | 14 675 (28) | 564 (31) | 15 239 (29) | |

| PCP | 647 (1) | 16 (1) | 663 (1) | |

| Specialist | 859 (2) | 16 (1) | 875 (2) | |

| Dermatologist | 35 394 (69) | 1205 (67) | 36 599 (69) | |

| Origin (public health care setting) | .2186 | |||

| Direct | 11 257 (10) | 553 (15) | 11 809 (10) | |

| PCP | 47 237 (42) | 1461 (40) | 48 698 (42) | |

| Specialist | 6024 (5) | 283 (8) | 6307 (5) | |

| Dermatologist | 47 087 (42) | 1340 (37) | 48 428 (42) | |

| Destination (public health care setting) | .2053 | |||

| Direct | 30 273 (27) | 805 (23) | 31 078 (27) | |

| PCP | 7143 (6) | 242 (7) | 7384 (6) | |

| Specialist | 2519 (2) | 32 (1) | 2551 (2) | |

| Dermatologist | 71 147 (64) | 2483 (70) | 73 629 (64) | |

| Territorial section | NA | |||

| ACCL | 13 888 (8) | 548 (10) | 14 436 (8) | |

| Andalusia | 24 862 (15) | 657 (12) | 25 518 (14) | |

| Balearic Islands | 3979 (2) | 48 (1) | 4028 (2) | |

| Canary Islands | 10 804 (6) | 274 (5) | 11 079 (6) | |

| Catalonia | 23 311 (14) | 1241 (22) | 24 553 (14) | |

| Center | 28 048 (16) | 1255 (22) | 29 303 (17) | |

| Galicia | 18 055 (11) | 440 (8) | 18 495 (10) | |

| Murcia | 1473 (1) | 28 (1) | 1502 (1) | |

| VNAR | 18 525 (11) | 373 (7) | 18 899 (11) | |

| Valencia | 28 431 (17) | 730 (13) | 29 161 (16) | |

Abbreviations: ACCL, Asturias-Cantabria-Castille Leon; NA, not applicable; PCP, primary care physician; VNAR, Basque Country-Navarre-Aragon.

Our study showed that primarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations account for a low percentage (3.2%) of diagnoses made by dermatologists in Spain. Overall, only 1.8% of the caseload of dermatovenereologists in Spain is accounted for by STIs per se, excluding from this percentage diagnoses of molluscum contagiosum in persons aged <18 years, pediculosis not otherwise specified, and scabies (and including lesions caused by anogenital HPV, scabies, syphilis, gonococcal urethritis and chlamydia, genital herpes, gonococcal genital infections, and chlamydia). Some differences were identified with respect to importance (most often the main presenting complaint) and patient age, as well as the origin of the consultations (in the case of patients seen at private clinics).

We t did not find any other studies with a similar approach. The diagnoses were selected by attempting, when possible, to include those associated with primarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations and other anogenital skin conditions.

Given that the data collected do not show the characteristics of patients with molluscum contagiosum (27.6% of the diagnoses selected), their inclusion probably overestimates the frequency of venereal disease overall and in patients aged <18 years (who accounted for 68.3% of cases of molluscum contagiosum). At the same time, however, it does not seem appropriate to exclude them, because the condition is likely to be an STI in adolescents aged <18 years. The diagnosis “pediculosis not otherwise specified” (coded separately from “pediculosis capitis”) may also be affected by the same problem, as it is not specified whether the site affected is the pubic region. Notwithstanding, its weight in the whole group of selected diagnoses is very low (0.28%). The first phase of the study also included diagnoses of lesions caused by HPV and herpes simplex affecting areas other than the anogenital region: the first group accounted for 1.20% of diagnoses overall, and the second, for 0.23%. Excluding the latter did not modify the differences between the variables studied (data not shown).

The dermatology caseload has increased in recent decades12,13. In parallel to the decrease in the incidence of STIs, dermatovenereologists clinics gradually gave less visibility to this subspecialty, albeit with a few exceptions. The data we report here show that treating STIs takes up a small part of the dermatologist’s activity, indicating that most patients with or at risk of STIs are likely seen outside the dermatology clinics and departments. To a large extent, this is due to the absence of direct access for these patients to specialized care in public centers (except in the few hospitals with specialist clinics with direct access), thus leading patients to be referred to primary care and the emergency department. Similarly, in our opinion, many patients and some health care professionals generally consult for STIs and anogenital dermatoses with gynecologists and urologists because they are unaware of the specific training of dermatologists in these fields. The fact that other specialists in private health care refer a significantly larger percentage of cases to the dermatologist highlights this lack of information among the general population (who, in this care setting do have direct access to a dermatologist) and the suitability of seeking alliances with colleagues in other specialties to increase awareness of dermatologists’ training in this area.

Our study has a series of strengths, such as the methodology used, which is representative of the activity of dermatologists in Spain, and its sample size, which ensures the accuracy of the results reported.

Our study is limited by the fact that although the sample is highly representative of MSDV clinics in Spain, the random sample did not include dermatologists from centers specialized in treating STIs. Such centers are not exclusive to Spain, and there are studies showing that they diagnose a much greater percentage of STIs than a dermatology department with a specialized clinic14. In our opinion, this explains why no HIV infection or extragenital STIs were recorded. While this would lead the role of the dermatologist in the treatment of these conditions to be undervalued, we believe that the bias is not very relevant, since such centers are rare and not all their activity involves dermatologists. Another limitation is the difficulty that arises, in some diagnoses, when determining whether the disease is an STI, as in molluscum contagiosum (which affected a high number of patients aged <18 years, in whom the condition is frequently not strictly an STI) and pediculosis not otherwise specified. In any case, this limitation does not modify the message of the current article, since it entails an overestimation of activity.

We believe that dermatovenereologists should lead the way in management of STIs. An example of this approach can be seen in the therapeutic algorithms proposed for anogenital verrucae15. We must make a collective effort to ensure that patients are aware of our specific training in the diagnosis and treatment of primarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations and anogenital dermatoses. In parallel, patients with or who are at risk of STIs and patients with anogenital dermatoses require streamlined care pathways. These should be direct, with as little bureaucracy as possible, and enable diagnosis, treatment, health care education, and suitable follow-up. Appropriate follow-up is essential if we are to break the epidemiological transmission chain, prevent new STIs, and ensure early detection of other infections, including HIV, whose risk clearly increases after diagnosis of certain STIs16,17.

ConclusionsThe caseload generated for dermatovenereologists by primarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations and other anogenital dermatoses is low in Spain. These diagnoses are more commonly the main reason for seeking care, and, while the direct pathway is the most common in private clinics, referral is by other specialists more frequently than in other conditions.

Venereology, primarily sexually transmitted infections and infestations, and anogenital dermatoses are areas of the specialty in which dermatovenereologists receive specific training. However, the limited presence of the dermatologist in the care of these diseases is due to factors such as the absence (and/or loss) of STI clinics and specialized centers, the lack of direct access to most of the public specialized clinics and departments in Spain, and the fact that many patients and some health professionals do not associate dermatovenereologists with STIs.

It is up to us to defend and—in some cases—reclaim the role of the dermatovenereologist in these areas of knowledge, with emphasis on the maintenance and potential restoration of specific STI clinics and centers specialized in treating STIs. To do so, the AEDV must become involved. In addition, these areas of the specialty must be strengthened to encourage multidisciplinary collaboration (with specialists in gynecology, urology, microbiology, internal medicine, and emergency department physicians) in order to achieve better care for patients with or at risk of STIs.

FundingThe DIADERM study was promoted by Fundación Piel Sana of the AEDV, which received financial support from Novartis. Novartis did not participate in the collection and analysis of data or in the interpretation of the study findings.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Martin-Gorgojo A, Comunión-Artieda A, Descalzo-Gallego MÁ, Arias-Santiago S, Molina-Leyva A, Gilaberte Y, et al. ¿Cuánta carga asistencial suponen las infecciones de transmisión predominantemente sexual y otras dermatosis anogenitales en las consultas de Dermatología en España? Resultados del muestreo aleatorio nacional DIADERM. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:22–29.