Leishmaniasis, an endemic infection in Spain, is caused by protozoan parasites of the Leishmania genus. Between 2010 and 2012, there was an outbreak of cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis in Fuenlabrada, Madrid.

ObjectivesTo describe the cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosed over a 17-month period at the dermatology department of Hospital de Fuenlabrada.

Material and methodsWe analyzed the epidemiological, clinical, histological, and microbiological features of each case and also evaluated the treatments administered and outcomes.

ResultsWe studied 149 cases. The incidence of cutaneous leishmaniasis showed a peak in the age range between 46 and 60 years and was similar in men and women. At the time of consultation, the lesions had been present for between 2 and 6 months in the majority of patients. The most common clinical presentation was with erythematous plaques and papules without crusts (52% of cases). Lesions were most often located in sun-exposed areas and were multiple in 57% of patients. In 67% of cases, the histological study showed non-necrotizing granulomatous dermatitis with no evidence of parasites using conventional staining methods. Diagnosis was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in 98% of patients. In the remaining cases, the histological study revealed Leishman-Donovan bodies in the skin. Intralesional pentavalent antimonials were the most commonly used drugs (76% of cases) and produced satisfactory results.

ConclusionsWe have presented a large series of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosed in the context of an outbreak. Multiple papules were the most common clinical presentation, with histology that showed non-necrotizing granulomatous dermatitis with no evidence of parasites. PCR of skin samples was the test that most frequently provided the diagnosis.

La leishmaniasis, infección endémica en España, está causada por protozoos del género Leishmania. Durante los años 2010-12 hubo un brote de leishmaniasis cutánea y visceral en Fuenlabrada, Madrid. Objetivos: Describir los casos de leishmaniasis cutánea (LC) diagnosticados durante 17 meses en el Servicio de Dermatología del Hospital de Fuenlabrada.

Material y métodoEstudiamos variables epidemiológicas, clínicas, histológicas, microbiológicas y terapéuticas de cada caso.

ResultadosSe recogieron 149 pacientes. Encontramos una incidencia similar en varones que en mujeres, la edad más frecuente fue entre 46-60 años. El tiempo de evolución presentaba un pico de máxima frecuencia entre los 2 y 6 meses. La forma clínica más habitual fue la de pápulas y placas eritematosas sin costra (52%). En el 57% de los casos las lesiones eran múltiples. La localización más común fue en áreas fotoexpuestas. El estudio histológico mostró en el 67% de los pacientes una dermatitis granulomatosa no necrotizante sin parásitos con tinciones habituales. La reacción en cadena de la polimerasa (PCR) para Leishmania confirmó el diagnóstico en el 98% de los casos. En los demás el estudio histológico de la piel identificó cuerpos de leishmanias. Los antimoniales pentavalentes intralesionales fueron los fármacos más empleados (76%), con resultado satisfactorio.

ConclusionesPresentamos una serie amplia de casos de LC en el contexto de un brote. La forma más habitual fue la aparición de múltiples pápulas y, la forma histológica, la dermatitis granulomatosa no necrotizante en la que no se observaron leishmanias. La PCR en piel fue la prueba más importante para alcanzar el diagnóstico.

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease caused by more than 20 species of protozoa of the genus Leishmania. It is transmitted by the bite of female sandflies of the genera Phlebotomus (Old World) and Lutzomyia (New World). Pets and wild animals are the usual reservoir and source of the infection (zoonotic transmission), although the disease can also spread from human to human (anthroponotic transmission).1 The disease is endemic in more than 80 countries in Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Southern Europe. In Spain, most cases of leishmaniasis—whether visceral (VL) or cutaneous (CL)—are caused by Leishmania infantum and are distributed along the Mediterranean coast and in Aragon and the center of the country. Although it is a notifiable disease,1 leishmaniasis is probably underreported.

Oriental sores are the typical clinical presentation of acute CL in Spain. These lesions start as asymptomatic or slightly pruritic papules in exposed areas and progress to firm plaques or erythematous nodular lesions that, in about half of cases, develop a central ulcer and an overlying seropurulent crust.1

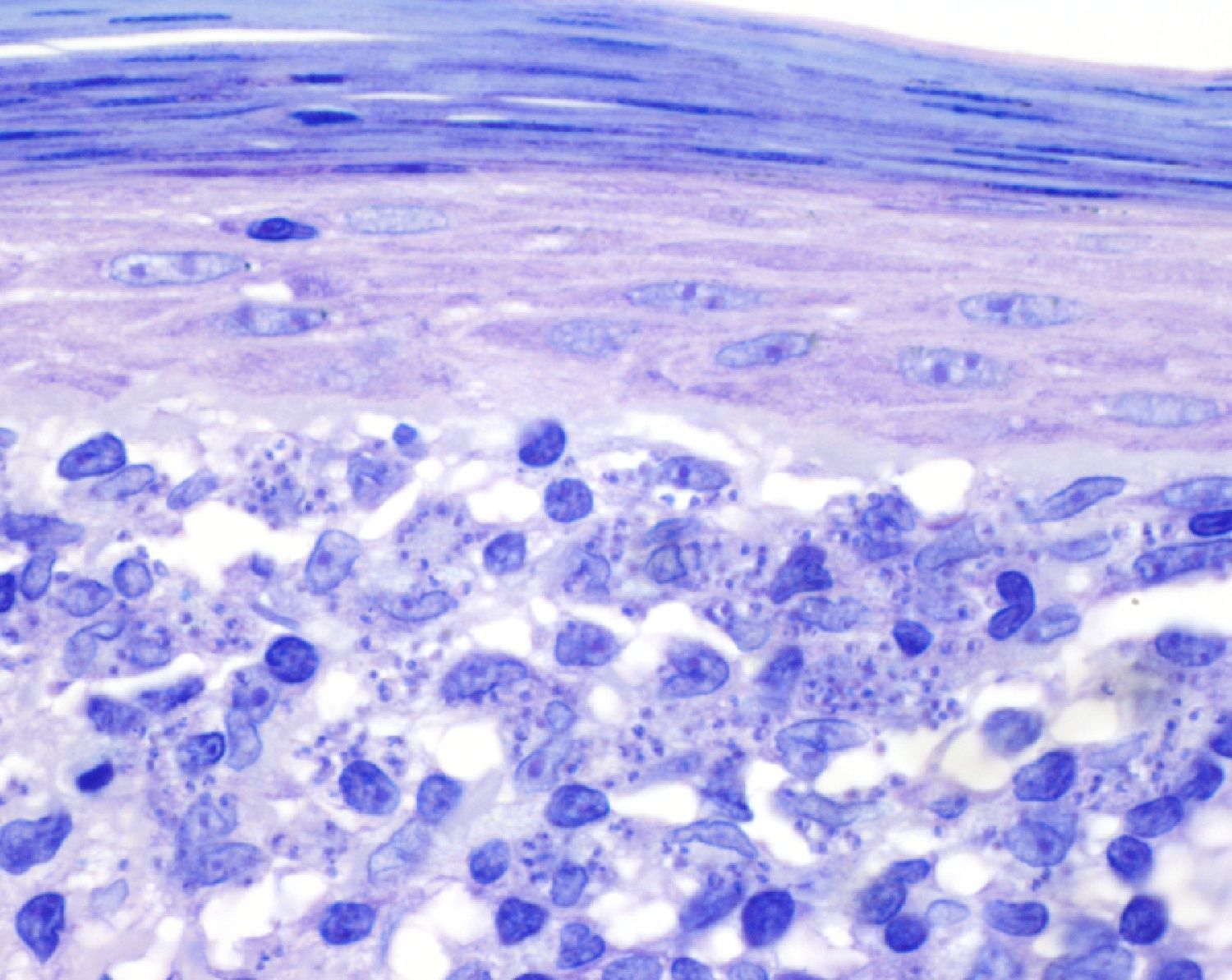

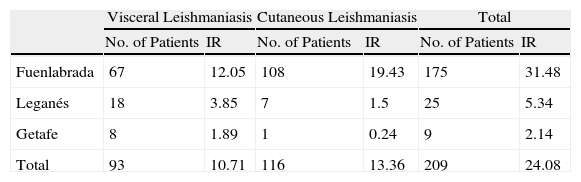

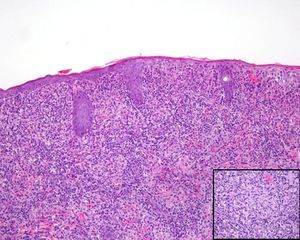

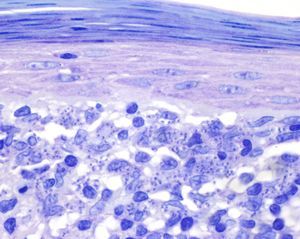

The histologic features of CL depend on the stage of evolution of the lesion. In the initial stages, typical findings include a dense, diffuse inflammatory dermal infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes containing amastigotes. As the lesion progresses, a granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate develops and the amastigotes decrease in number, thus becoming more difficult to identify.1 In 2010 and 2011, there was an outbreak of CL and VL in the Autonomous Community of Madrid,2 with most cases occurring in the cities of Leganés and Fuenlabrada.2 Between July 2009 and December 2011, 67 cases of VL (annual cumulative incidence of 12.05 cases per 100 000 inhabitants) and 108 cases of CL (annual cumulative incidence of 19.43 cases per 100 000 inhabitants) were reported in Fuenlabrada (Table 1).2 Most of the patients lived in or had regularly visited the northwestern part of central Fuenlabrada, which borders the Leganés city limits.3

Reports of Leishmaniasis Between July 2009 and December 2011 in the Cities of Fuenlabrada, Leganés, and Getafe.a

| Visceral Leishmaniasis | Cutaneous Leishmaniasis | Total | ||||

| No. of Patients | IR | No. of Patients | IR | No. of Patients | IR | |

| Fuenlabrada | 67 | 12.05 | 108 | 19.43 | 175 | 31.48 |

| Leganés | 18 | 3.85 | 7 | 1.5 | 25 | 5.34 |

| Getafe | 8 | 1.89 | 1 | 0.24 | 9 | 2.14 |

| Total | 93 | 10.71 | 116 | 13.36 | 209 | 24.08 |

Abbreviation: IR, annual cumulative incidence rate per 100000 inhabitants.

Source: Brote comunitario de leishmaniasis en los municipios de Fuenlabrada, Leganés y Getafe (2009-2011).2

The initial hypothesis to explain the increase in the number of cases of leishmaniasis in these cities was the existence of 1 or more risk areas for bites by infected Phlebotomus sandflies, particularly in the late summer of 2010, leading to a temporal-spatial clustering of infected individuals.3 Dogs, cats, black rats, hares, and rabbits were investigated as reservoirs.4 Because leishmaniasis infection was found in only 7% of the dogs examined, it was determined that the increase in the number of cases in humans could not be explained solely by these animals.5 Therefore, other food sources for the vectors—including hares, rabbits, cats, and rats—were investigated.5 Thirty percent of the hares studied to date have been positive for Leishmania parasites, but some samples have not yet been analyzed to confirm the presence of L infantum.5

We present 149 cases of CL diagnosed in the dermatology department of Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada, Madrid.

Material and MethodsWe recorded the cases of CL (with or without visceral or lymph node involvement) diagnosed in the dermatology department of Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada in a 17-month period (October 2010 to February 2012). The hospital serves a population of approximately 222 500 people in the cities of Fuenlabrada, Moraleja de Enmedio, and Humanes de Madrid. Diagnosis was confirmed by direct observation of the parasite in a skin biopsy specimen or by a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result for Leishmania organisms in fresh or paraffin-embedded skin specimens. For each patient, the following parameters were recorded: age, sex, place of residence, pet ownership, history of immunosuppression, prior treatments, time from onset of lesions to consultation, clinical presentation of lesions (morphology, number, site, and size), associated symptoms, cutaneous histologic findings, PCR result for Leishmania organisms in skin specimens, results of additional tests (laboratory tests, chest radiograph, cultures, etc.), systemic involvement (enlarged lymph nodes, fever, sweating, weight loss, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, etc.), treatment administered, and response to treatment.

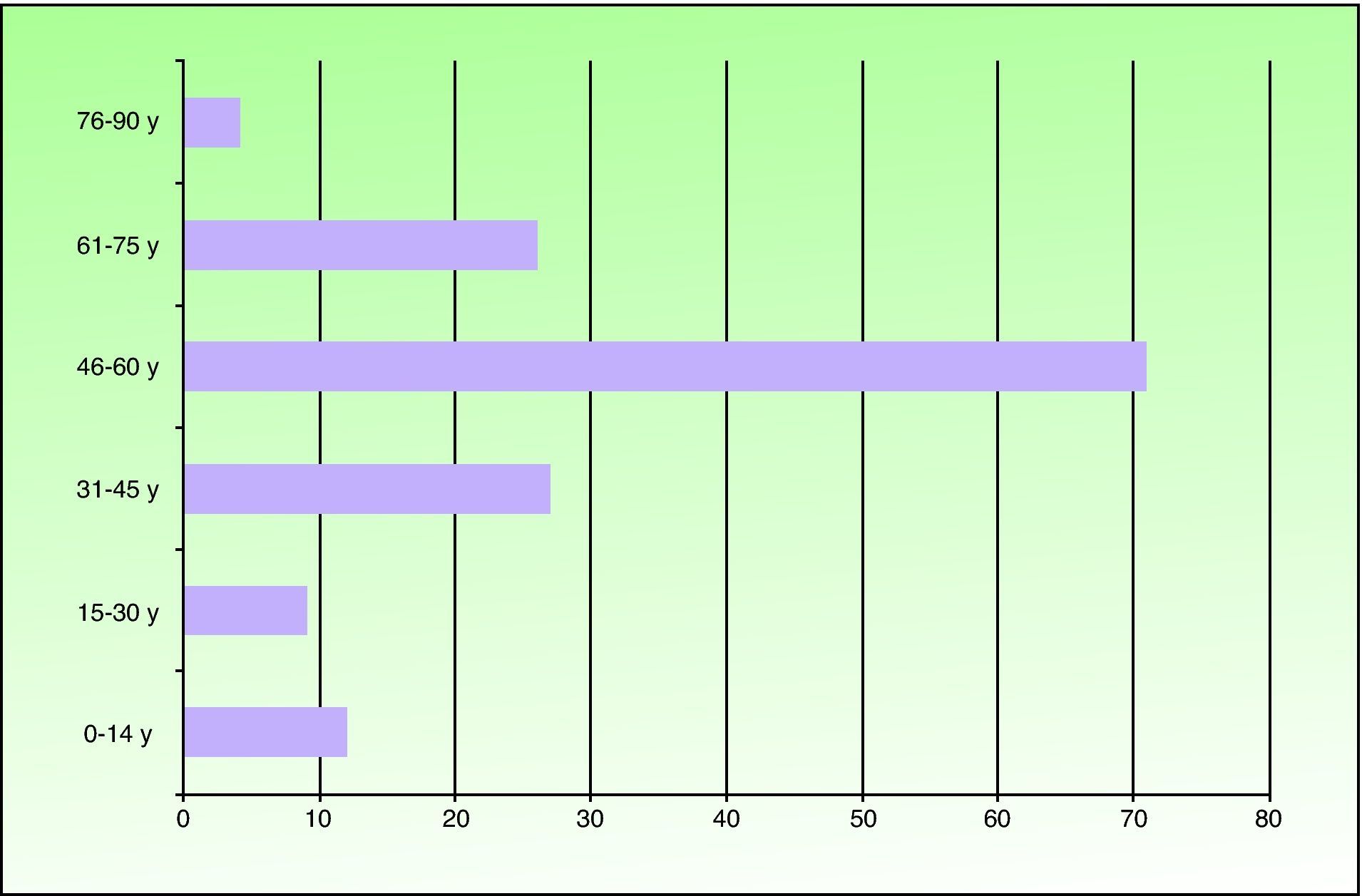

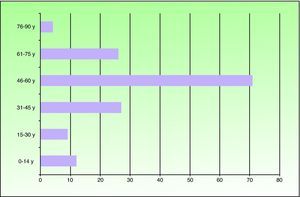

ResultsOf the 149 patients studied, 78 (52%) were men and 71 (48%) were women. Patients ranged in age from 6 months to 81 years and the mean age was 49.2 years. The most frequent age range was 46 to 60 years (71 patients). Twelve patients were under the age of 14 years (Fig. 1). Seventy-one patients (48%) lived in the northern part of Fuenlabrada, near the Leganés city limits. More than half of the patients regularly visited parks (Parque de la Paz, Parque de Polvoranca, Bosque Sur) and commuter railway stations in this area. Ten patients were dog owners.

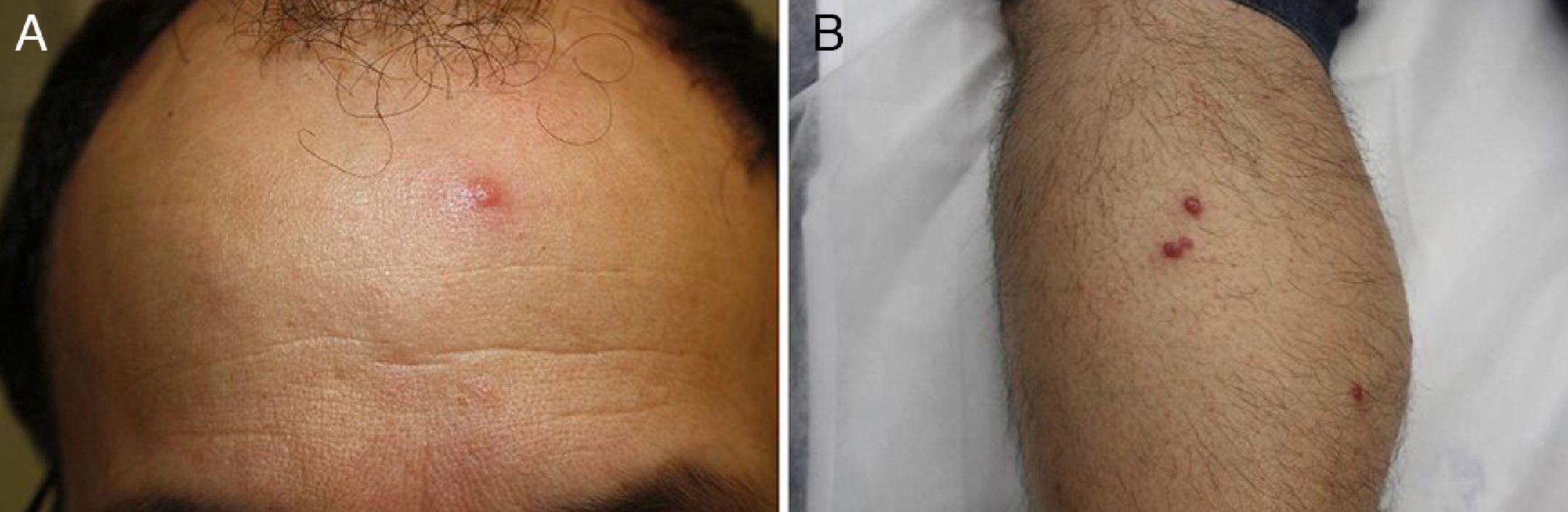

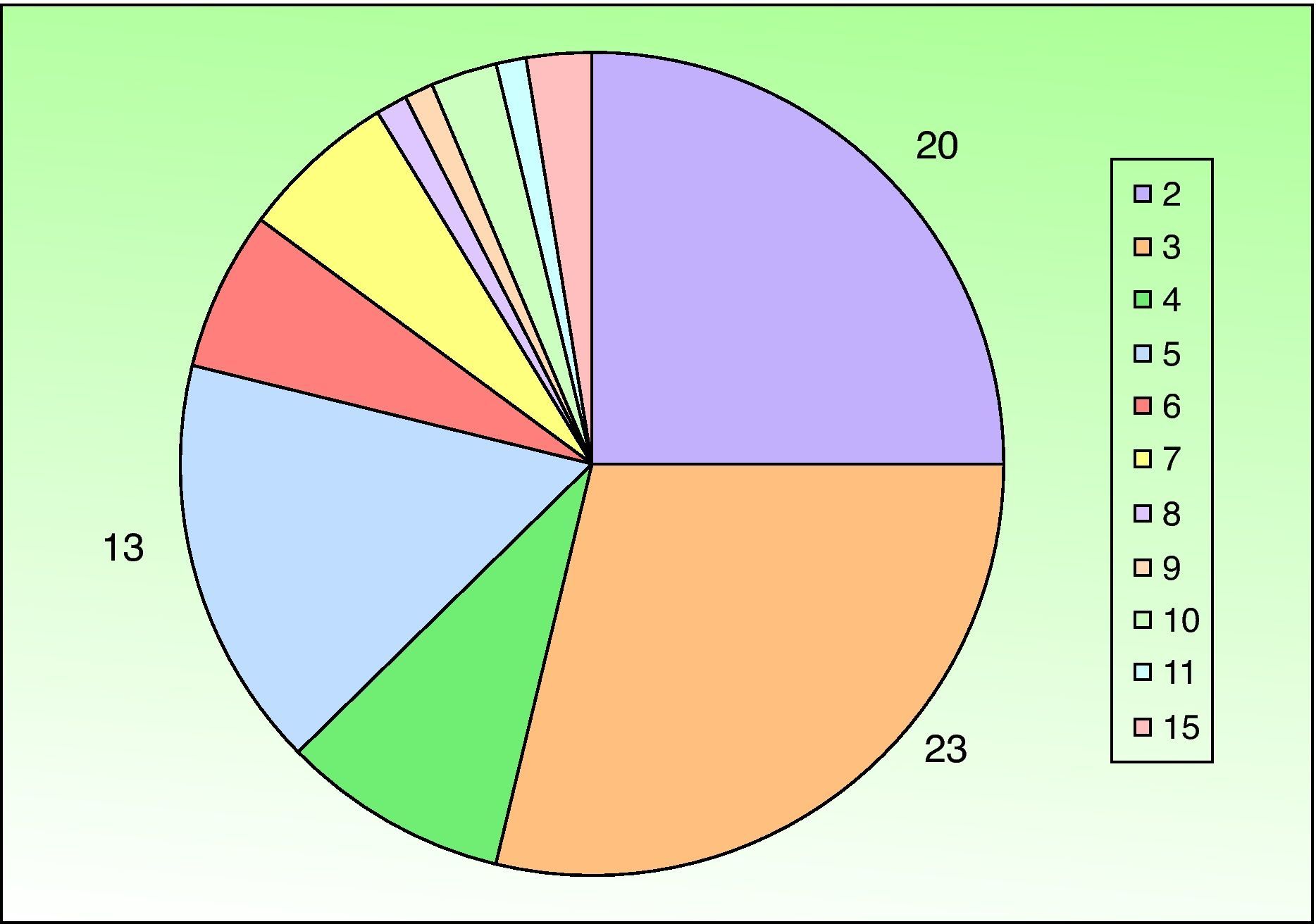

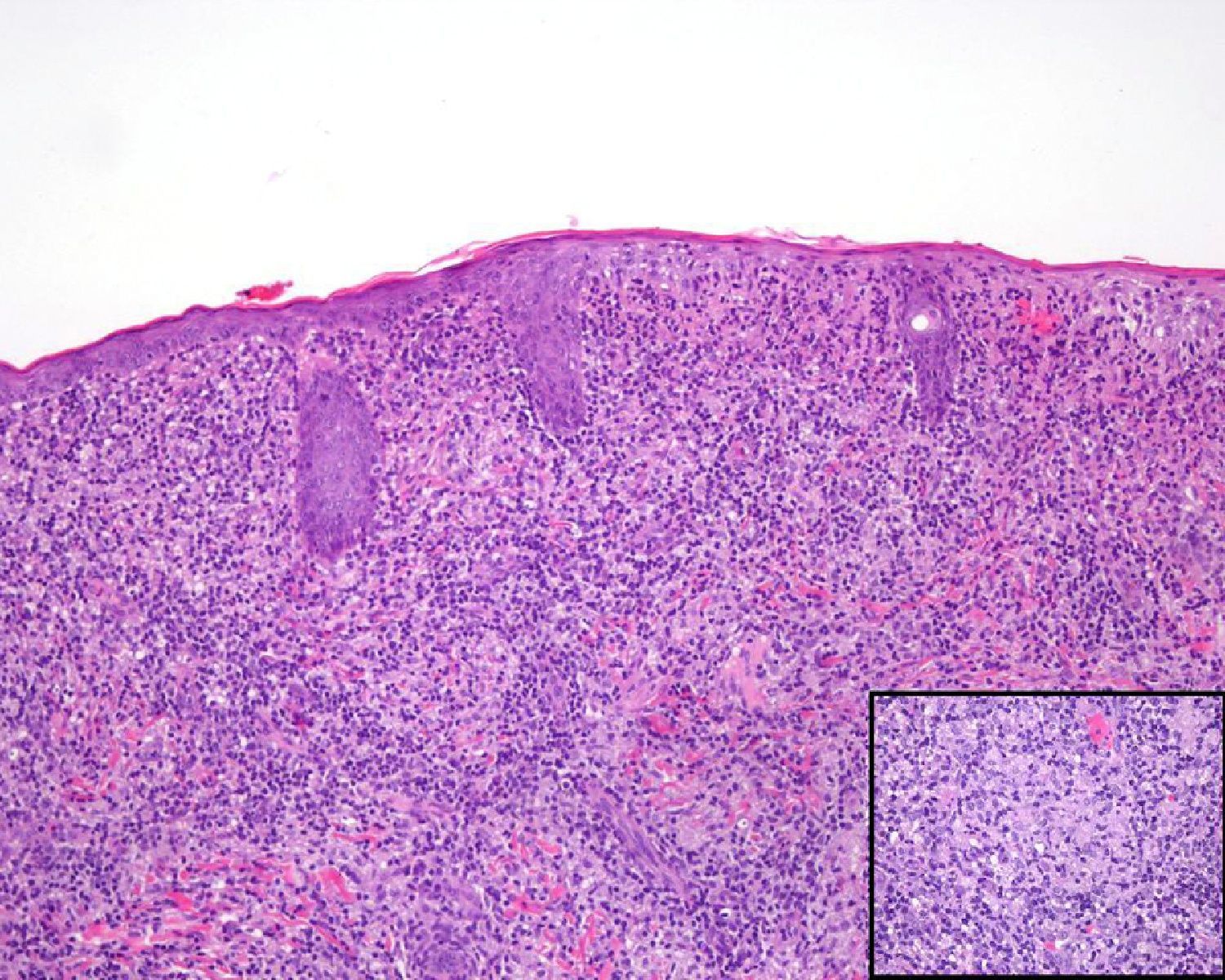

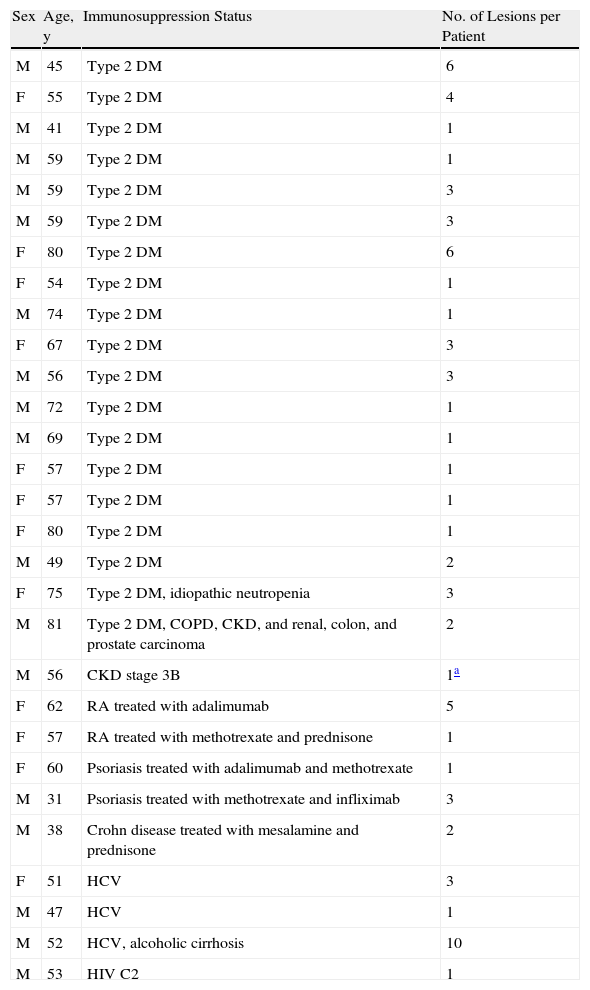

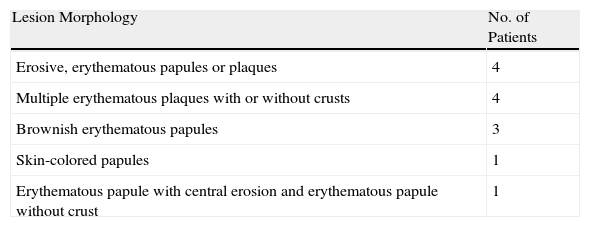

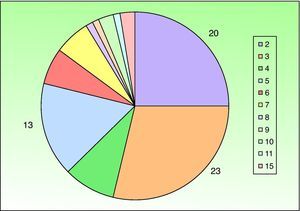

A past history suggestive of immunosuppression was found in 29 patients (19%). Table 2 shows the distribution of these patients by type of disease, the most common of which was type 2 diabetes mellitus (17 patients). Three patients were being treated with biologic agents: a 62-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis receiving adalimumab, a 31-year-old man with psoriasis receiving methotrexate and infliximab, and a 60-year-old woman with psoriasis receiving methotrexate and adalimumab. Forty-six patients (31%) had previously been treated for their lesions; 26 had received high-potency corticosteroids and/or topical antibiotics. Time to consultation ranged from 2 weeks to 42 months. In 85 cases (57%), the patients sought medical attention between 2 and 6 months after the lesions first appeared. The lesions were morphologically classified as a) smooth or scaly erythematous papules or plaques without crusts, b) erythematous papulonodular lesions with crusts (Oriental sores), c) erythematous, orange-colored (lupoid) lesions, d) psoriasiform lesions, or e) other lesions; this last group included various clinical presentations and accounted for 9% of cases (Table 3). There were 78 patients (52%) with smooth or scaly erythematous papules or plaques without crusts (Fig. 2A), 50 (33%) with Oriental sores (Fig. 3), 7 (5%) with lupoid lesions, and 1 (1%) with psoriasiform lesions. Sixty-four patients (43%) had a single lesion and 85 (57%) had multiple lesions (Fig. 2B). In these 85 patients, the most common presentation was 2 or 3 lesions (43 cases); the largest number of lesions was 15, seen in 2 patients (Fig. 4). The size of the lesions at the time of consultation ranged from 2 to 80mm. In 49 patients (33%), the diameter of the lesions was 2 to 5mm. Most lesions were located on the limbs: the upper limbs were affected in 51 patients (34%) and the lower limbs were affected in 34 (23%). Lesions were located on the head in 27 patients (18%) and on the trunk in 13 patients (9%). Twenty-four patients (16%) had lesions in more than 1 anatomic region, with considerable distance between the sites (for example, lower limbs and face or upper and lower limbs). The lesions were asymptomatic in 115 patients (77%). Thirty-four patients (23%) had symptoms: itching in 30 cases, local pain in 3, and bleeding in 1. In 100 cases (67%), histologic examination of the skin lesions revealed a diffuse, inflammatory, lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with plasma cells. The histiocytes had an epithelioid morphology and formed nonnecrotizing granulomas (Fig. 5). Ziehl-Neelsen, Giemsa, and periodic acid-Schiff stains were negative for mycobacteria, Leishmania parasites, and fungi. These findings were consistent with nonnecrotizing granulomatous dermatitis. In 46 patients (31%), skin biopsy revealed a dense, inflammatory infiltrate in the upper and deep dermis composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and several multinucleated giant cells. The cytoplasm of some of the histiocytes contained Leishmania organisms (Fig. 6). Histologic findings were compatible with nonspecific ulceration in 1 patient, chronic lymphohistiocytic dermatitis in another, and sarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis in yet another. PCR tests for detection of Leishmania organisms in fresh or paraffin-embedded skin specimens were ordered in 133 cases (89%). In 131 (98%) of these, a positive result was obtained and L infantum was identified as the causative agent. The 2 patients (2%) with a negative PCR result had previously undergone a skin biopsy that had revealed Leishman-Donovan bodies within histiocytes; the PCR results were therefore interpreted as false negatives. PCR tests were not performed in 16 cases (11%) because histiocytes containing Leishmania parasites had been directly observed in the histologic study. Skin cultures were performed for 20 patients and L infantum was isolated in 11 cases. In the remaining cases, the samples were not cultured because a diagnosis was established more quickly by PCR testing.

Characteristics of Patients With History of Immunosuppression.

| Sex | Age, y | Immunosuppression Status | No. of Lesions per Patient |

| M | 45 | Type 2 DM | 6 |

| F | 55 | Type 2 DM | 4 |

| M | 41 | Type 2 DM | 1 |

| M | 59 | Type 2 DM | 1 |

| M | 59 | Type 2 DM | 3 |

| M | 59 | Type 2 DM | 3 |

| F | 80 | Type 2 DM | 6 |

| F | 54 | Type 2 DM | 1 |

| M | 74 | Type 2 DM | 1 |

| F | 67 | Type 2 DM | 3 |

| M | 56 | Type 2 DM | 3 |

| M | 72 | Type 2 DM | 1 |

| M | 69 | Type 2 DM | 1 |

| F | 57 | Type 2 DM | 1 |

| F | 57 | Type 2 DM | 1 |

| F | 80 | Type 2 DM | 1 |

| M | 49 | Type 2 DM | 2 |

| F | 75 | Type 2 DM, idiopathic neutropenia | 3 |

| M | 81 | Type 2 DM, COPD, CKD, and renal, colon, and prostate carcinoma | 2 |

| M | 56 | CKD stage 3B | 1a |

| F | 62 | RA treated with adalimumab | 5 |

| F | 57 | RA treated with methotrexate and prednisone | 1 |

| F | 60 | Psoriasis treated with adalimumab and methotrexate | 1 |

| M | 31 | Psoriasis treated with methotrexate and infliximab | 3 |

| M | 38 | Crohn disease treated with mesalamine and prednisone | 2 |

| F | 51 | HCV | 3 |

| M | 47 | HCV | 1 |

| M | 52 | HCV, alcoholic cirrhosis | 10 |

| M | 53 | HIV C2 | 1 |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; F, female; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; M, male; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Unclassifiable Skin Lesions.

| Lesion Morphology | No. of Patients |

| Erosive, erythematous papules or plaques | 4 |

| Multiple erythematous plaques with or without crusts | 4 |

| Brownish erythematous papules | 3 |

| Skin-colored papules | 1 |

| Erythematous papule with central erosion and erythematous papule without crust | 1 |

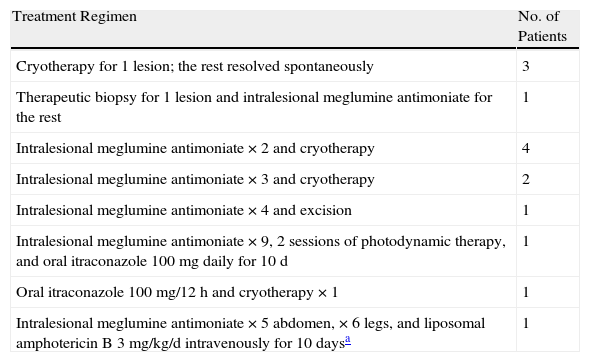

Patients with a past history of immunosuppression and/or systemic manifestations underwent further testing. Laboratory tests including complete blood count, biochemistry, and autoimmune studies were performed in 39 cases. Relevant abnormalities were detected in just 3 cases: a woman with rheumatoid arthritis, who was positive for antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and anti-DNA antibodies; a man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, who had neutropenia; and a woman with a past history of idiopathic neutropenia, who had neutropenia and was positive for anti-Ro 60 antibodies and ANAs. Sixteen patients underwent chest radiography. A pulmonary granuloma was detected in a 43-year-old woman. An induration greater than 10mm was observed in a 48-year-old man with no relevant past history 72hours after Mantoux testing, but no abnormalities were seen in the chest radiograph. Systemic manifestations were observed in 6 patients. In 1 case, a 47-year-old man had weight loss, but this was not considered to be due to leishmaniasis because physical examination was otherwise normal (no enlarged lymph nodes or swelling of abdominal organs) and additional tests revealed no other abnormalities. In the other 5 patients (4 men and 1 woman), enlarged lymph nodes were observed in the head and neck. Only 1 of these patients, a man with stage 3B chronic kidney disease, had a past history of immunosuppression. Of the patients with enlarged lymph nodes, 3 had erythematous papulonodular lesions with crusts and 2 had erythematous papules without crusts. One patient with the latter lesion morphology had 11 lesions, whereas the other 4 had single lesions. In 4 patients, the affected lymph node groups were in the drainage basin of the site of the leishmaniasis skin lesions. Laboratory tests and abdominal ultrasound revealed no abnormalities. The results of pathologic examination of the lymph nodes by fine-needle aspiration biopsy (in 4 cases) and by analysis of resected lymph node tissue (in 1 case) were normal in 1 patient, consistent with reactive lymphadenitis in 1 patient, and consistent with leishmanial lymphadenitis in 3 patients. Specific treatment for the lesions was prescribed for 103 patients (69%), 78 of whom received intralesional meglumine antimoniate. The number of injections per lesion ranged from 1 to 8, with 1-week intervals between doses. The dose used in each session ranged from 0.5 to 1mL per lesion. The lesions resolved in 62 patients (79%). The remaining 16 patients have not yet completed treatment but are responding well. A perilesional inflammatory reaction secondary to the treatment appeared in 9 cases (6%). Fourteen patients followed combination therapy regimens with intralesional meglumine antimoniate and other treatments, which are described in detail in Table 4. The lesions resolved in all cases. Cryotherapy was used successfully as monotherapy in 9 cases (6%). The number of sessions per lesion ranged from 1 to 3. Two patients with leishmanial lymphadenitis received intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (3mg/kg/d, 5 doses) and their lesions healed. In a third patient with leishmanial lymphadenitis, the skin lesions and enlarged lymph nodes resolved spontaneously. The patient with reactive lymphadenitis received 3 intralesional injections of meglumine antimoniate and the lesions resolved. In a patient with enlarged lateral cervical lymph nodes and normal cytology, 4 intralesional injections of meglumine antimoniate were required to achieve cure. No specific treatment was prescribed in 32 cases (21%): 9 patients who were lost to follow-up, 15 patients whose lesions resolved spontaneously, and 8 patients in whom skin biopsy was of diagnostic and therapeutic value.

Patients Who Received Combination Therapy.

| Treatment Regimen | No. of Patients |

| Cryotherapy for 1 lesion; the rest resolved spontaneously | 3 |

| Therapeutic biopsy for 1 lesion and intralesional meglumine antimoniate for the rest | 1 |

| Intralesional meglumine antimoniate ×2 and cryotherapy | 4 |

| Intralesional meglumine antimoniate ×3 and cryotherapy | 2 |

| Intralesional meglumine antimoniate ×4 and excision | 1 |

| Intralesional meglumine antimoniate ×9, 2 sessions of photodynamic therapy, and oral itraconazole 100mg daily for 10 d | 1 |

| Oral itraconazole 100mg/12h and cryotherapy ×1 | 1 |

| Intralesional meglumine antimoniate ×5 abdomen, ×6 legs, and liposomal amphotericin B 3mg/kg/d intravenously for 10 daysa | 1 |

Finally, 14 patients (10%) have not yet started treatment.

DiscussionThis case series is notable as it presents a large number of patients diagnosed with CL in a particular geographic area over a period of 17 months. Other series published in Spain have had a smaller number of cases and a shorter follow-up period.6–9 In previous studies, slightly more than half of the patients were women,8,9 whereas in our study more men were affected, although the difference was not significant. Also of note in our series is the low incidence of CL in children, with patients under the age of 14 years accounting for 8% of all cases. In previous series, 56% of cases were in children under the age of 5 years,7 38% in children under the age of 12 years,8 and 30% in children under the age of 14 years.9 The authors of the previous studies attribute the higher incidence of CL among children to immune system immaturity, greater skin penetrability, and longer exposure to the vector.

In our series there was a clear geographic clustering of cases around the northern part of Fuenlabrada. This area has recently undergone considerable environmental changes that have probably contributed to the proliferation of sandfly vectors and given rise to foci of leishmaniasis. These changes include the creation of parks, recreational lands, and a protected area that is home to a large population of hares and rabbits.10 Considering the discovery of infected hares in areas near the affected population and the absence of a proportional increase in the prevalence of the disease or infection in dogs, hares can be considered the reservoirs in this outbreak.10 This would suggest the existence of a sylvatic transmission cycle that has not yet been described in Spain10 and that would possibly require changes in epidemiologic surveillance measures.

Time to consultation (2-6 months) was slightly lower than that reported in previous studies (mean of 6-8 months).7–9 The most common lesion size in our series (2-5mm) was slightly smaller than that reported in previous studies (mean diameter of approximately 1cm).7–9 The most common clinical presentation of CL in our series was multiple smooth or scaly erythematous papules or plaques without crusts. This finding contrasts with those of earlier studies6–9 in which the most common morphology was a single papulonodular lesion with crust (Oriental sore). In recent years, atypical forms of CL have been seen more frequently in routine clinical practice. One of these forms consists of multiple asymptomatic erythematous papules or nodules that are very similar, except in size; they can be located very close to or distant from each other.11 These atypical forms can develop as a result of the interaction of several factors related to the Leishmania organisms (species, tropism, infectious capacity, pathogenicity, and virulence), to the vector (number of sandfly bites, species, and salivary composition), and to the host (immune status and genetic susceptibility).1 In contrast to previous studies,7–9 in our series lesions were most frequently located on the limbs. A possible explanation for this is that most of the sandfly bites in our patients occurred in the summer, when people wear clothing that leaves the arms and legs uncovered. In approximately two-thirds of cases, the histologic features of the skin lesions were consistent with nonnecrotizing granulomatous dermatitis, a finding that by itself is inconclusive. In these cases, Leishmania species detection by PCR of skin biopsy specimens was necessary in order to confirm the diagnosis of CL. PCR is a diagnostic method with high sensitivity (75%-77% to 100%) and specificity (100%) for the detection of Leishmania DNA in cytology brush specimens12 and biopsy specimens.13 Cytology brush PCR testing has proved to be a useful diagnostic tool that can make invasive procedures such as biopsy unnecessary.12 According to the reviewed studies,12–17 PCR is useful in lesions in which parasites are few or not visible and which have histologic features consistent with granulomatous dermatitis on conventional microscopic examination. The technique can be applied to either fresh12,13,17 or paraffin-embedded14–16 tissue specimens. It also allows the identification of Leishmania species with species-specific primers.15,17 We propose that Leishmania species detection by PCR should be routinely performed as part of the assessment of nonspecific granulomatous dermatitis, even in the case of lesions that are clinically atypical or not very suspicious for CL.14–16 Three of our patients developed leishmanial lymphadenitis, a form of leishmaniasis associated with the inflammation of regional lymph nodes, with or without skin lesions,18–20 and no systemic involvement. The pathogenesis of leishmanial lymphadenitis has not been fully elucidated, but it has been suggested that it may be caused by the spread of amastigote-infected macrophages to lymph nodes or by the transport of Leishmania antigens by Langerhans cells in the skin to lymph nodes.18–20 Some patients develop leishmanial lymphadenitis after receiving intralesional treatment for skin lesions.18–20 The objectives of treatment for CL are to accelerate the healing process, minimize the risk of unattractive residual scarring, and prevent disease progression.21,22 Various treatment modalities have been used, including topical, intralesional, and systemic drugs and physical methods.1,9,21,22 However, the level of evidence for these treatments is as of yet limited as they have not yet been studied in well-designed clinical trials.21,22 In Spain, intralesional meglumine antimoniate is the first-line treatment for CL in patients with a single, small lesion (<4cm), although good results have also been seen in cases with multiple or larger lesions.9 The drug is administered by injection at the periphery of the lesion until complete blanching is achieved. Various doses and regimens have been used.9 In our series, 78 patients were treated with intralesional meglumine antimoniate; the lesions resolved in 79% of cases with acceptable cosmetic results and very low systemic toxicity. In previous case series,8,9 most patients were treated with the same drug and achieved cure. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen is used primarily in children and is generally effective and safe.1,9,21 In dark skin, however, it can leave residual hypopigmentation. As in our patients, cryotherapy can be used alone or in combination with other treatments, such as intralesional meglumine antimoniate.9 The use of photodynamic therapy to treat CL has become increasingly common, with excellent cosmetic outcomes.21 The required doses for this therapy are not yet well defined, but a regimen of 1 session per week for a month has been described in the literature.21 The mechanism of action appears to be related to the destruction of tissues and macrophages.21 Photodynamic therapy can also be combined with other treatments.21 We used photodynamic therapy to treat a patient with an erythematous plaque with crusts on the right leg after intralesional meglumine antimoniate, administered on 9 occasions, had failed. When no improvement was observed after 2 sessions of photodynamic therapy, the patient was started on oral itraconazole (100mg daily for 10 days), which led to cure. In small, isolated lesions, surgical excision has been used as a therapeutic option.1,8,9 Excision biopsy was of diagnostic and therapeutic value in 8 of our patients.

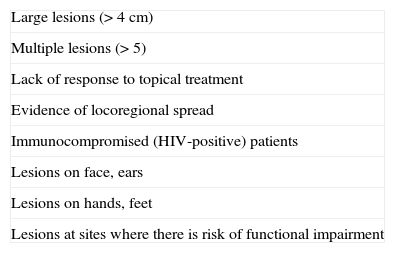

In recent years, 5% topical imiquimod has been used, with variable results, in combination with meglumine antimoniate in patients with CL that had not responded to meglumine antimoniate alone.23,24 Patients with CL have also been treated successfully with topical imiquimod after failing to respond to liposomal amphotericin B.25 Although further studies are needed, imiquimod appears to act by stimulating a local immune response and activating macrophages, thus controlling the disease.24Table 5 shows some criteria for the initiation of systemic treatment of CL that we found in our review of the literature.26,27 For years, pentavalent antimonials have been the drugs of choice in this treatment modality. However, because of their considerable nephrotoxicity and cardiotoxicity and their adverse effects (arthralgia, myalgia, fever, vomiting, elevated liver enzyme levels), in recent years they have been replaced by liposomal amphotericin B, which has been associated with fewer complications in the cases reported.21,22,26,27 This drug is administered intravenously at a dose of 1 to 1.5mg/kg/d for 21 days or 3mg/kg/d for 10 days.21,22,26,27 The 2 patients in our series who received liposomal amphotericin B achieved cure and had no adverse effects. Azoles (ketoconazole and itraconazole) act by inhibiting ergosterol synthesis in the parasite membrane. Various doses have been used and the results have been inconsistent.1,9 While in some cases Old World CL resolves spontaneously after several months, as occurred in 15 of our patients, it should generally be treated because it affects cosmetically important exposed areas and because it is associated with the risk of spread and mucosal involvement.1,9 In conclusion, we would like to emphasize that in this series of patients with CL both the sylvatic transmission cycle (with hares as reservoirs) and the clinical presentation of the lesions (multiple erythematous papules without crusts) were uncommon for cases of CL in Spain. Furthermore, on the basis of our experience, we believe that in endemic areas Leishmania species detection by PCR should be routinely performed as part of the assessment of patients with nonnecrotizing granulomatous dermatitis and no other findings.

Indications for Systemic Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis.a

| Large lesions (>4 cm) |

| Multiple lesions (>5) |

| Lack of response to topical treatment |

| Evidence of locoregional spread |

| Immunocompromised (HIV-positive) patients |

| Lesions on face, ears |

| Lesions on hands, feet |

| Lesions at sites where there is risk of functional impairment |

Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed their hospital's protocol on the publication of data concerning patients and that all patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their verbal informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects referred to in this article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Aguado M, et al. Brote de leishmaniasis cutánea en el municipio de Fuenlabrada. Actas Dermo-sifiliogr. 2013;104:334–42.