Nevoid basal cell carcinoma (BCC) syndrome, or Gorlin syndrome, is a rare autosomal dominant disorder associated with mutations in the patched 1 gene, PTCH1. It is characterized by the presence of multiple BCCs in association with disorders affecting the bones, the skin, the eyes, and the nervous system.

We describe 6 cases of nevoid BCC syndrome evaluated in our department. Palmoplantar pitting was observed in all 6 patients, multiple BCCs in 5 patients (83%), skeletal anomalies in 3 patients (50%), and odontogenic keratocysts in 1 patient (17%).

We would like to stress the importance of early diagnosis and treatment in nevoid BCC syndrome and the need for continuous, long-term follow-up by a multidisciplinary team.

El síndrome del nevo basocelular o síndrome de Gorlin es un trastorno hereditario infrecuente, de carácter autosómico dominante, asociado a la mutación del gen PATCHED1. Se caracteriza por la presencia de múltiples carcinomas basocelulares y alteraciones óseas, cutáneas, oftalmológicas y neurológicas asociadas.

Presentamos 6 pacientes evaluados en nuestro Servicio con diagnóstico de síndrome del nevo basocelular. Entre las manifestaciones observadas se destacan la presencia de hoyuelos palmoplantares en todos los pacientes (100%), carcinomas basocelulares múltiples en 5 pacientes (83%), malformaciones congénitas en 5 sujetos (83%), alteraciones esqueléticas en tres de ellos (50%) y queratoquistes odontógenos en un paciente (17%).

Es de nuestro interés hacer hincapié en la importancia del diagnóstico y tratamiento temprano de esta enfermedad, debiendo realizar un seguimiento multidisciplinario a lo largo de toda la vida de estos pacientes.

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma (BCC) syndrome, also known as Gorlin syndrome and basal cell nevus syndrome, is a rare autosomal dominant disorder associated with mutations in the patched 1 gene (PTCH1). Its clinical manifestations can be both congenital and acquired. We present a series of 6 patients with nevoid BCC syndrome evaluated in our department between 1987 and 2010. We describe the clinical characteristics and additional tests performed, provide details on the clinical course and treatments initiated, and briefly review the topic.

Case DescriptionsCase 1The patient was a 12-year-old boy who was referred with odontogenic keratocysts diagnosed at age 9 years (Fig. 1). He had no family history of interest.

Physical examination revealed macrocephaly and facial asymmetry, with missing teeth. Numerous light-brown round hyperpigmented elevated lesions (approximately 3mm in diameter) were visible on the arms, legs, and trunk. He also had palmoplantar pitting (Fig. 2).

A diagnosis of congenital dermal melanocytic nevus was made based on biopsy of 3 of the lesions on the trunk. The patient did not return to the clinic after the lesion was excised.

Case 2The patient was a girl aged 6 years at her first visit. Physical examination revealed macrocephaly, hypertelorism, epicanthus, and frontal bossing. She had several light-brown round elevated lesions (3–5mm in diameter) on the face (4 lesions), neck (1 lesion), flexor surface of the legs (4 lesions), and left buttock (1 lesion) (Fig. 3). The lesions first appeared at age 4 years. She also had palmoplantar pitting. The patient had no family history of interest.

Histopathology of one of the neck lesions revealed BCC.

A number of additional tests were performed, as follows:

- 1.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain: increased anteroposterior diameter of both lateral ventricles (atria and corpus).

- 2.

Nuclear magnetic resonance image (MRI) scan of the spinal column: mild scoliosis and slight rotation of the vertebrae involved.

- 3.

Chest x-ray: bifid third rib (left) and high scapula (Sprengel deformity)

- 4.

Panoramic radiograph of the jaws, abdominal ultrasound, and ECG: normal

The patient developed 3 new BCCs on the neck and trunk. All 3 were completely removed. At the age of 16 years, the patient underwent posterior arthrodesis with instrumentation (T1 to T10) to correct the scoliosis. After 10 years of follow-up in our department, the patient is now seen at an adult institution, since she is now over the age for care at our hospital.

Case 3The patient was a girl aged 2 years at her first visit. Physical examination revealed macrocephaly, hypertelorism, broad forehead, deviated gluteal cleft, and palmoplantar pitting (Fig. 4). She had more than 30 light-brown round elevated lesions (2–4mm in diameter) on the face (left lower eyelid), neck, trunk, legs, and arms. The patient had no family history of interest.

Histopathology of one of the lesions confirmed a diagnosis of pigmented BCC.

The additional tests performed were as follows:

- 1.

MRI of the brain: type 1 Chiari malformation and polymicrogyria.

- 2.

Chest x-ray: bifid fifth rib.

- 3.

Panoramic radiograph of the jaws, abdominal ultrasound, and ECG: normal.

The patient was on treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil for 4 months. Her response was excellent, and the BCCs gradually disappeared. The lesion on the lower left eyelid was removed surgically, and histopathology confirmed BCC. Two years and 3 months later, she is still being monitored by a multidisciplinary team. Since many of her lesions are compatible with BCC, photodynamic therapy is now being considered.

Case 4The patient was a 2-year-old boy whose physical examination revealed 24 round elevated lesions that had been present on the face, trunk, and legs since age 1 year. Histopathology performed at another center confirmed the diagnosis of BCC. The patient also presented macrocephaly and palmoplantar pitting. He had no family history of interest.

A number of additional tests were performed, as follows:

- 1.

Cranial and facial CT: cranial asymmetry (smaller on the right side), enlarged subarachnoid spaces with increased intrahemispheric distance.

- 2.

X-ray of the chest and spinal column: dorsolumbar scoliosis and Sprengel deformity.

- 3.

Abdominal ultrasound, ECG, and ophthalmological examination: normal.

At age 3 years, 1 of the lesions on the trunk was removed. Histopathology confirmed BCC. The treatment prescribed for this lesion and the others was topical imiquimod, 5%, applied 3 times per week for 2 months. Partial remission was achieved; therefore, 5-fluorouracil was prescribed for 4 weeks, and the lesions disappeared. However, the lesions reappeared, and photodynamic therapy was started but subsequently suspended after 2 sessions because the patient complained of intense pain. Topical 5-fluorouracil was restarted, and the lesions gradually remitted. Three years after the first visit, the patient is still being followed at our center.

Case 5The patient was a boy aged 16 years at his first visit. He had been diagnosed with congenital measles and consulted because of a peculiar phenotype. Similar clinical observations were made for his mother and brother (Case 6).

Physical examination revealed macrocephaly, low-set ears, high arched palate, micrognathia, convergent strabismus of the left eye, and prosthetic right eye. The patient also had palmoplantar pitting, pigmented round elevated lesions with pearly borders on the nose and trunk, and multiple melanocytic nevi on the face, trunk, arms, and legs.

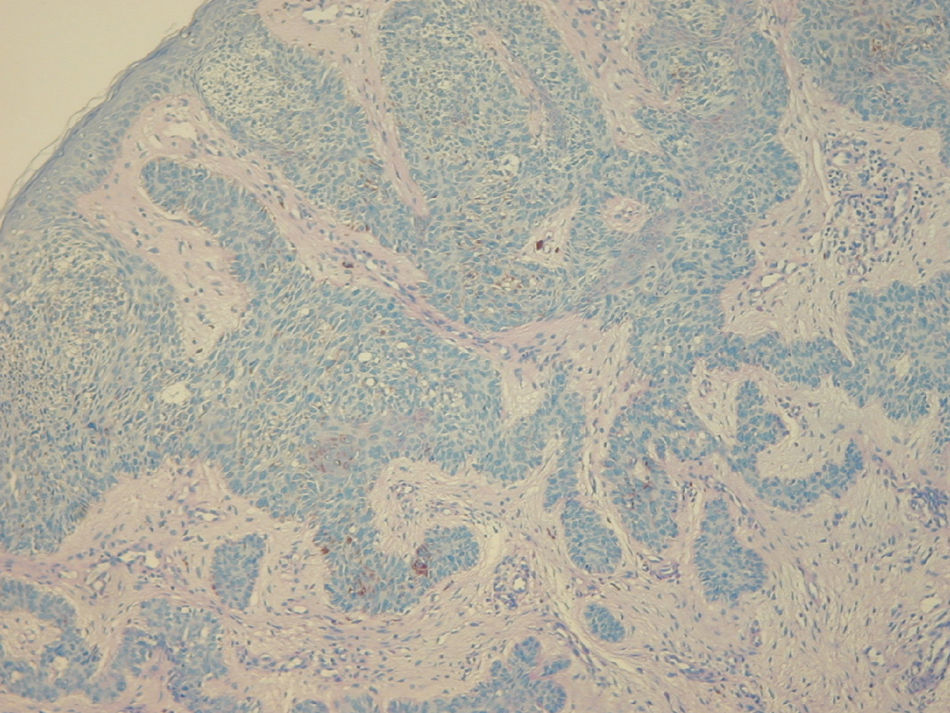

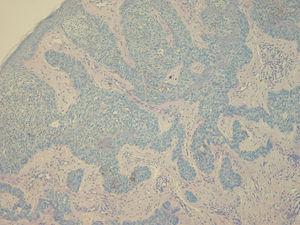

Histopathology of one of the lesions from the chest revealed BCC with a cord pattern (Fig. 5).

The additional tests performed were as follows:

- 1.

MRI scan of the central nervous system and face: morphological abnormalities of the right eyeball, with loss of sphericity associated with hyperintense signal in T2 and widening of the optic nerve (compatible with a history of congenital measles).

- 2.

Abdominal ultrasound: hepatic steatosis.

The patient initiated treatment with topical imiquimod, 5%, applied 3 times per week for 10 weeks. A partial response was observed; therefore, photodynamic therapy was prescribed, although it was not eventually administered, as the patient did not return to our center.

Case 6The patient was a boy aged 8 years at his first visit. He was diagnosed with nevoid BCC syndrome at age 3 years. He attended for treatment of multiple histopathology-confirmed BCC lesions.

Both his mother and brother (case 5) had been diagnosed with the same disease.

He had received topical 5-fluorouracil, 5%, and imiquimod, 5%, for treatment of the lesions and achieved a partial response.

Physical examination revealed macrocephaly, prominent forehead, hypertelorism, prognathism, and poor dental occlusion. In addition, multiple hyperpigmented lesions were observed on the face, neck, trunk, and groin; some were flat and others elevated, measuring 2mm to 8mm in diameter. The patient also presented palmoplantar pitting.

The additional tests performed were as follows:

- 1.

CT scan of the brain and face: calcifications on both occipital lobes.

- 2.

Ultrasound examination of the abdomen and pelvis and panoramic radiograph of the jaws: normal.

Photodynamic therapy was prescribed; however, the patient has not returned after 1 year of follow-up.

DiscussionNevoid BCC syndrome is an autosomal dominant disease with high penetrance and variable expression caused by a mutation in the PTCH1 gene on chromosome 9 (q22.3-q31).1–5 This gene encodes a transmembrane glycoprotein that participates in the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway, which regulates a wide variety of processes, including embryogenesis, carcinogenesis, tissue repair during chronic inflammatory processes, and maintenance of homeostasis during these processes.5

Prevalence is estimated to be between 1/50 000 and 1/250 000 and varies depending on the geographical region.3,5

The skin manifestations include pigmented BCC lesions, palmoplantar pitting, acrochordons, milia-like cysts, and epidermal cysts.1,6,7

Facial appearance is characterized by the presence of macrocephaly, frontal bossing, synophrys, wide nasal bridge, hypertelorism, and prognathism. Cleft palate may also be observed.6,7Ophthalmologic disorders are observed in 10% to 15% of patients and include hypertelorism, strabismus, congenital cataracts, congenital glaucoma, coloboma (iris, choroid, and optic nerve), and microphthalmia.1,7,8 Odontogenic keratocysts are found in 90% of patients with nevoid BCC syndrome,1 and there have been reports of ameloblastomas, odontogenic myxomas, fibrosarcomas, and squamous cell carcinomas resulting from these lesions.1,2,5–9

Skeletal manifestations include increased height, macrocephaly, and rib abnormalities.2,5–7 Sprengel deformity (congenital abnormal elevation of one or both scapulae) affects 10% to 40% of patients with nevoid BCC syndrome.1,6Findings also include cardiac fibromas,1,6,7 ovarian fibromas or calcifications, renal disorders, hypogonadism, cryptorchidism, and gynecomastia.1,5–7

Central nervous system involvement can take the form of calcification of the falx cerebri (70%–85%), the tentorium cerebelli, the petroclinoid ligament, and the diaphragm of the sella turcica. Other features include cysts in the choroid plexus, agenesis of the corpus callosum, empty sella syndrome, hydrocephalus, meningioma, craniopharyngioma, astrocytoma, and medulloblastoma.1,2,6,7,10

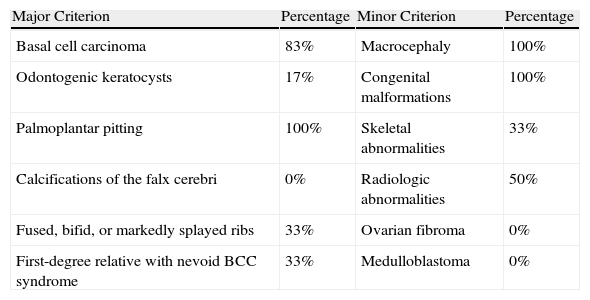

In our series, all the patients (Table 1) had the peculiar phenotype of this disease, with hypertelorism, macrocephaly, and palmoplantar pitting, which is a characteristic but not pathognomic sign. Multiple BCC lesions were observed in 5 children (83%); both these and palmoplantar pitting appeared between the ages of 2 and 8 years. Only 1 patient had odontogenic keratocysts, whose low incidence in our series was probably due to the young age of the sample. As for skeletal abnormalities, 2 children had Sprengel deformity, 2 had rib abnormalities, and 2 scoliosis. The neurological manifestations included calcifications in both occipital lobes in one child and type 1 Chiari malformation in another. The latter has not been previously associated with nevoid BCC. Of note, only 2 patients had a family history of the disease.

Diagnostic Criteria in the Patients Assessed.

| Major Criterion | Percentage | Minor Criterion | Percentage |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 83% | Macrocephaly | 100% |

| Odontogenic keratocysts | 17% | Congenital malformations | 100% |

| Palmoplantar pitting | 100% | Skeletal abnormalities | 33% |

| Calcifications of the falx cerebri | 0% | Radiologic abnormalities | 50% |

| Fused, bifid, or markedly splayed ribs | 33% | Ovarian fibroma | 0% |

| First-degree relative with nevoid BCC syndrome | 33% | Medulloblastoma | 0% |

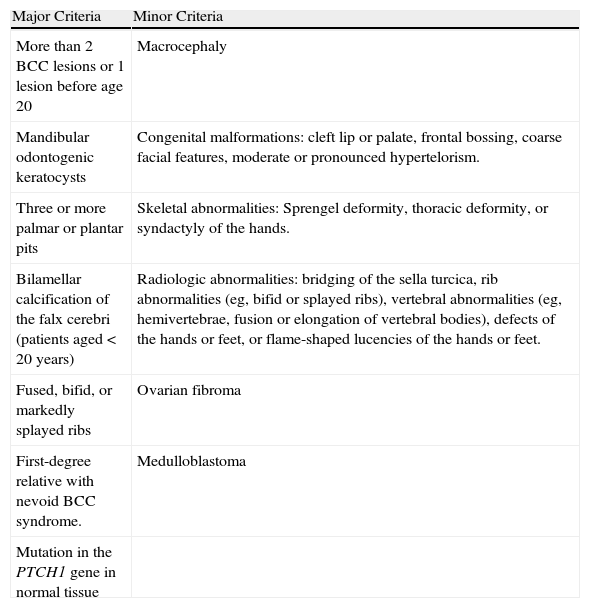

The diagnosis of BCC syndrome should take into account the modified criteria of Kimonis et al.1,2,11 (Table 2).

Diagnostic Criteria of Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome.

| Major Criteria | Minor Criteria |

| More than 2 BCC lesions or 1 lesion before age 20 | Macrocephaly |

| Mandibular odontogenic keratocysts | Congenital malformations: cleft lip or palate, frontal bossing, coarse facial features, moderate or pronounced hypertelorism. |

| Three or more palmar or plantar pits | Skeletal abnormalities: Sprengel deformity, thoracic deformity, or syndactyly of the hands. |

| Bilamellar calcification of the falx cerebri (patients aged < 20 years) | Radiologic abnormalities: bridging of the sella turcica, rib abnormalities (eg, bifid or splayed ribs), vertebral abnormalities (eg, hemivertebrae, fusion or elongation of vertebral bodies), defects of the hands or feet, or flame-shaped lucencies of the hands or feet. |

| Fused, bifid, or markedly splayed ribs | Ovarian fibroma |

| First-degree relative with nevoid BCC syndrome. | Medulloblastoma |

| Mutation in the PTCH1 gene in normal tissue |

Modified from Kimonis et al.1,2,11 Diagnosis: 2 major criteria and 1 major or 2 minor criteria.

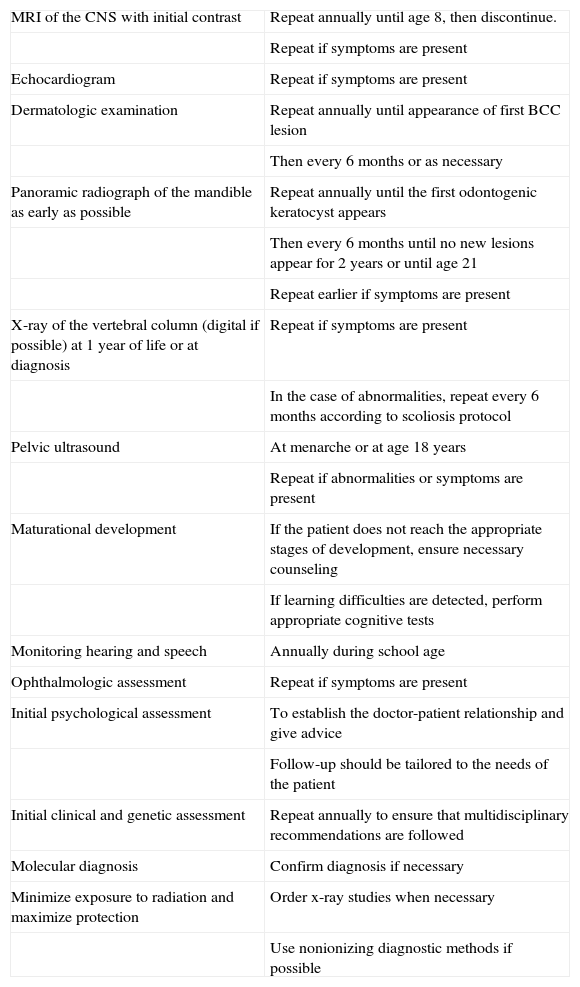

Given the complex nature of this syndrome and the diversity of its clinical manifestations, additional tests should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and monitor the clinical course (Table 3).12

Complementary Tests for the Diagnosis and Follow-up of Pediatric Patients With Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome.

| MRI of the CNS with initial contrast | Repeat annually until age 8, then discontinue. |

| Repeat if symptoms are present | |

| Echocardiogram | Repeat if symptoms are present |

| Dermatologic examination | Repeat annually until appearance of first BCC lesion |

| Then every 6 months or as necessary | |

| Panoramic radiograph of the mandible as early as possible | Repeat annually until the first odontogenic keratocyst appears |

| Then every 6 months until no new lesions appear for 2 years or until age 21 | |

| Repeat earlier if symptoms are present | |

| X-ray of the vertebral column (digital if possible) at 1 year of life or at diagnosis | Repeat if symptoms are present |

| In the case of abnormalities, repeat every 6 months according to scoliosis protocol | |

| Pelvic ultrasound | At menarche or at age 18 years |

| Repeat if abnormalities or symptoms are present | |

| Maturational development | If the patient does not reach the appropriate stages of development, ensure necessary counseling |

| If learning difficulties are detected, perform appropriate cognitive tests | |

| Monitoring hearing and speech | Annually during school age |

| Ophthalmologic assessment | Repeat if symptoms are present |

| Initial psychological assessment | To establish the doctor-patient relationship and give advice |

| Follow-up should be tailored to the needs of the patient | |

| Initial clinical and genetic assessment | Repeat annually to ensure that multidisciplinary recommendations are followed |

| Molecular diagnosis | Confirm diagnosis if necessary |

| Minimize exposure to radiation and maximize protection | Order x-ray studies when necessary |

| Use nonionizing diagnostic methods if possible |

Adapted from Bree et al.12

Dermoscopy is a useful complementary approach in the diagnosis of BCC. It reveals large blue-gray ovoid nests or globules in the early stages of lesions measuring less than 3mm in diameter and arborizing vessels in larger lesions. Palmoplantar pitting can also be evaluated using dermoscopy, which can reveal the presence of red globules arranged in parallel lines within slight skin-colored depressions with irregular borders.13–15

The differential diagnosis should include Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome (characterized by the presence of BCC, follicular atrophoderma, hypohidrosis, and hypertrichosis), Muir Torre syndrome (multiple sebaceous adenomas, multiple keratoacanthomas, and visceral neoplasms with predominance in the digestive tract), multiple papular trichoepithelioma, Rombo syndrome (vermiculate atrophoderma, hypotrichosis, cyanosis, and trichoepithelioma), basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome (milia-like cysts, palmoplantar pitting, hypotrichosis, and basaloid follicular hamartomas), exposure to arsenic, and xeroderma pigmentosum.1,6,16

Treatment should be multidisciplinary, given the diverse clinical manifestations patients can present throughout life.

As for the BCCs, excision of lesions with safety margins is the standard approach in most patients. However, considering the number and characteristic recurrent nature of the lesions, several alternative approaches have been proposed. These include Mohs surgery,1,5 CO2 and erbium-yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser,1,17 electrocoagulation, and/or cryosurgery.17

Photodynamic therapy is a well-recognized treatment for multiple superficial or nodular BCCs. It has a cure rate that ranges from 85% to 98% and cosmetic outcome is acceptable.1,5,17–22 Several authors have reported treatment of nevoid BCC syndrome with photodynamic therapy.

In 2004, Itkin and Gilchrest20 reported on 2 women aged 21 and 47 years with nevoid BCC syndrome and multiple BCC lesions who were treated with δ-aminolevulinic acid and 417nm blue light. Complete clinical remission was achieved for 89% of superficial lesions on the face in one patient (8 of 9 lesions) and 67% of superficial lesions on the extremities in the other (18 of 27 lesions). Remission was less complete for nodular lesions on the face (31%, 5 out of 16 lesions). A partial response was observed in the remaining lesions. The authors followed the patients for 8 months. No recurrences were recorded, and the cosmetic outcome was excellent. One report discussed the case of a patient with nodular BCC syndrome who was successfully treated with tin ethyl etiopurpurin and photodynamic therapy.19 No evidence of recurrence was detected after 6 months of follow-up. Wang et al21 performed a clinical trial comparing photodynamic therapy with cryosurgery in the treatment of BCC. Efficacy was similar in both groups, but more sessions were required with photodynamic therapy than with cryosurgery. However, time to cure and cosmetic outcome were considerably better with photodynamic therapy. Several publications have shown that topical photosensitizers, such as 5-aminolevulinic acid or methyl-aminolevulinate, are useful for the treatment of superficial BCC lesions, although nodular BCC lesions, which are more frequent in nevoid BCC syndrome, have proven to be refractory. In these cases, systemic photosensitizers such as porphymer sodium have been used with satisfactory results.1,13,18,19 Loncaster et al22 reported on 33 patients aged between 9 and 79 years with nevoid BCC syndrome who received photodynamic therapy based on topical and systemic photosensitizers depending on the depth of the lesions (assessed using ultrasound), which was reduced by 68% at 12 months and 65% at 24 months. The cosmetic outcome of lesions treated using this approach was excellent, although more evidence is necessary from a greater number of patients. The most commonly reported complication with this modality was the burning sensation patients experienced during the procedure.

A high cure rate has been recorded with the application of imiquimod cream, 5%, 3 times per week for 6 to 8 weeks and 5-fluorouracil cream, 5%, twice daily for 12 weeks.1,13,17 Oral retinoids have been used to inhibit the appearance and stimulate partial regression of tumoral lesions.1,6,17 However, the prolonged course of therapy necessary means that management is hindered by multiple side effects.6 Radiotherapy is contraindicated, as it can predispose the patient to new lesions.1,6,17

Unfortunately, there are no studies on the effectiveness of the different options to treat BCC in children.

Goldberg et al23 published the results of a phase 1 clinical trial with the drug GDC-0449. This agent is used to treat advanced BCC and inhibits the hedgehog pathway through interaction with a transmembrane G protein, which, in turn, could lead to regression of BCC.24

Given the age of our patients, we found that excision was indicated only in those cases involving single or large lesions. For patients with multiple small nodular or superficial BCC lesions, treatment with imiquimod, 5%, and/or 5-fluorouracil, 5%, or photodynamic therapy proved highly satisfactory.

ConclusionNevoid BCC syndrome is an uncommon condition that should be suspected in the case of a characteristic phenotype associated with the appearance of multiple lesions in patients aged less than 20 years. Early diagnosis enables multidisciplinary follow-up to be initiated in order to avoid the possible complications of this disease and thus improve quality of life.

Management of BCCs is very challenging. Several therapeutic alternatives, both surgical and nonsurgical, are available and can be used alone or in combination. Unfortunately, there are no large-scale studies on the treatment of BCCs in this syndrome. The best evidence we have comes from case series or clinical trials with small samples.

The first-choice approach for the tumor lesions should be conservative, as nonaggressive as possible, and highly effective, taking into account the early onset and recurrent nature of the lesions. In order to optimize outcome, the treating physician should rely on the best available clinical evidence, personal experience, and patient characteristics.

Given the age of patients and the different types of lesion, as well as their size, location, and number, the best therapeutic option available is to combine the different treatments taking into account the aforementioned factors and studying each patient on an individual basis.

Since scientific evidence on the management of BCC in patients with nevoid BCC syndrome is weak, there is clearly a need for more clinical trials on the effectiveness of the different treatment options, especially in children, the population in which these tumors most often appear.

Finally, it is essential to stress the role of photographs in training, regular clinical follow-up to detect new lesions early, and appropriate genetic counseling owing to the autosomal dominant nature of this disease.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Samela PC, et al. Síndrome del nevo basocelular: experiencia en un hospital pediátrico. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:426–33.