Managing atopic dermatitis, one of the most common dermatologic conditions, is often challenging. To establish consensus on recommendations for responding to various situations that arise when treating atopic dermatitis, a group of hospital pharmacists and dermatologists used the Delphi process. A scientific committee developed a Delphi survey with two blocks of questions to explore the group's views on (1) evaluating response to treatment in the patient with atopic dermatitis and (2) cooperation between the dermatology department and the hospital pharmacy service. The experts achieved an overall rate of consensus of 86% during the process. Conclusions were that dermatologists and hospital pharmacists must maintain good communication and coordinate their interventions to optimize the management of atopic dermatitis and patients’ responses to treatment.

El control de la dermatitis atópica (DA), una de las dermatosis más frecuentes, es en muchas ocasiones un reto terapéutico. En el presente estudio se ha utilizado la metodología Delphi con el objetivo de poner en común las perspectivas del dermatólogo y del farmacéutico hospitalario ante el manejo de la DA y establecer una serie de recomendaciones de actuación adaptadas a las diferentes situaciones que plantea la enfermedad. El cuestionario Delphi ha sido definido por un comité científico y se ha dividido en 2 bloques: (1) valoración de la respuesta al tratamiento del paciente con DA y (2) cooperación entre Dermatología y Farmacia Hospitalaria (FH). Como resultado del estudio, se ha alcanzado un consenso total del 86%. Se concluye que el dermatólogo y el farmacéutico hospitalario deben tener una buena comunicación y trabajar coordinados para conseguir optimizar el manejo del paciente con DA y su respuesta al tratamiento.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory disease of immunologic origin, characterized by the presence of pruritus and eczema, and with a range of manifestations depending on the age of the patient and other factors.1–3 It is estimated that AD is one of the most common skin diseases, associated with a high socioeconomic cost.4 Between 20% and 25% of children are affected,1 in particular babies. In adults, as many as 17% may have the condition,5 with a third of cases being moderate to severe in intensity.6

The pathophysiology of AD includes deregulation of the immune system and compromised skin barrier,2 leading to a large number of atopic and nonatopic comorbidities.7 Overall, these have a major negative impact on the quality of life of patients with this disease4 and there is a clear association with anxiety and depression.8,9

Despite recent advances in therapeutics for AD, efficient control of moderate/severe disease is still challenging. In addition to the appropriate use of the pharmacological treatments available, collaboration between specialties could be a beneficial factor for improving the health and quality of life of patients, as well as for increasing the effectiveness of treatment, so contributing to the sustainability of the health system. From the perspective of an increasingly restrictive pharmacoeconomic setting, the only way to ensure that innovative and expensive drugs can be used is to apply consensus protocols and pharmacotherapeutic guidelines drawn up not only by the corresponding clinical specialty, in this case dermatology, but also by the hospital pharmacy.

In view of the above, and given that many of the treatments indicated for moderate/severe AD are dispensed by the hospital pharmacy, a collaboration between dermatology and hospital pharmacy would seem appropriate. In order to address this aspect, in this article, the vision of dermatologists and hospital pharmacists has been shared, with the following objectives: assessment of the current situation, identification of points of conflict in management of AD, definition of working strategies, and proposal of recommendations for action in different situations.

Material and methodsScientific committeeThe scientific committee was made up of four specialists (two dermatologists and two hospital pharmacists) with experience in AD. The functions of said committee consisted of performing an updated review of the medical literature on care of patients with AD, designing the Delphi questionnaire, and selecting an expert panel who would respond to the questionnaire. Once the responses from the expert panel were obtained, the scientific committee was also charged with analyzing the results, debating them, and drawing conclusions.

Expert panelSelection of the expert panel was made such that there were the same number of dermatologists as pharmacists – 26 dermatologists and 25 hospital pharmacists – who had notable experience in the management of patients with AD and who were recognized within this disease area with published studies and articles on the topic. Most of the experts were drawn from Catalonia and the Autonomous Region of Madrid, in line with the greater number of professionals in these regions; other regions were also represented however, with professionals from seven additional autonomous regions (see supplementary material, Tables S1 and S2).

Delphi methodologyBased on scientific evidence and clinical practice, a consensus was drawn up using the Delphi methodology10 to evaluate any differences of opinion identified, as well as to make recommendations for management and identify possibilities of collaboration between two specialties.

The Delphi questionnaire was designed jointly by dermatology and hospital pharmacy. Initially, 73 assertions were defined to reach consensus on. These were grouped into two blocks: (1) management and assessment of the patient (35 assertions) and (2) collaboration between dermatology and hospital pharmacy (38 assertions).

For statistical analysis of the Delphi questionnaire, see Annex S1 in the supplementary material.

ResultsThe 51 experts responded to two rounds of the Delphi questionnaire, using a numerical Likert scale; in addition, comments were permitted for each response.

The 73 assertions defined by the scientific committee were submitted to the first round for consensus. The expert panel reached an initial consensus in 57 (78%) of the 73 assertions. The 16 assertions for which consensus was not reached were submitted to a second round, reaching agreement in 6 (38% consensus in the second round). The total number of assertions with consensus, taking into account both rounds, was 63, so the final percentage agreement was 86%. There was no disagreement in any of the assertions.

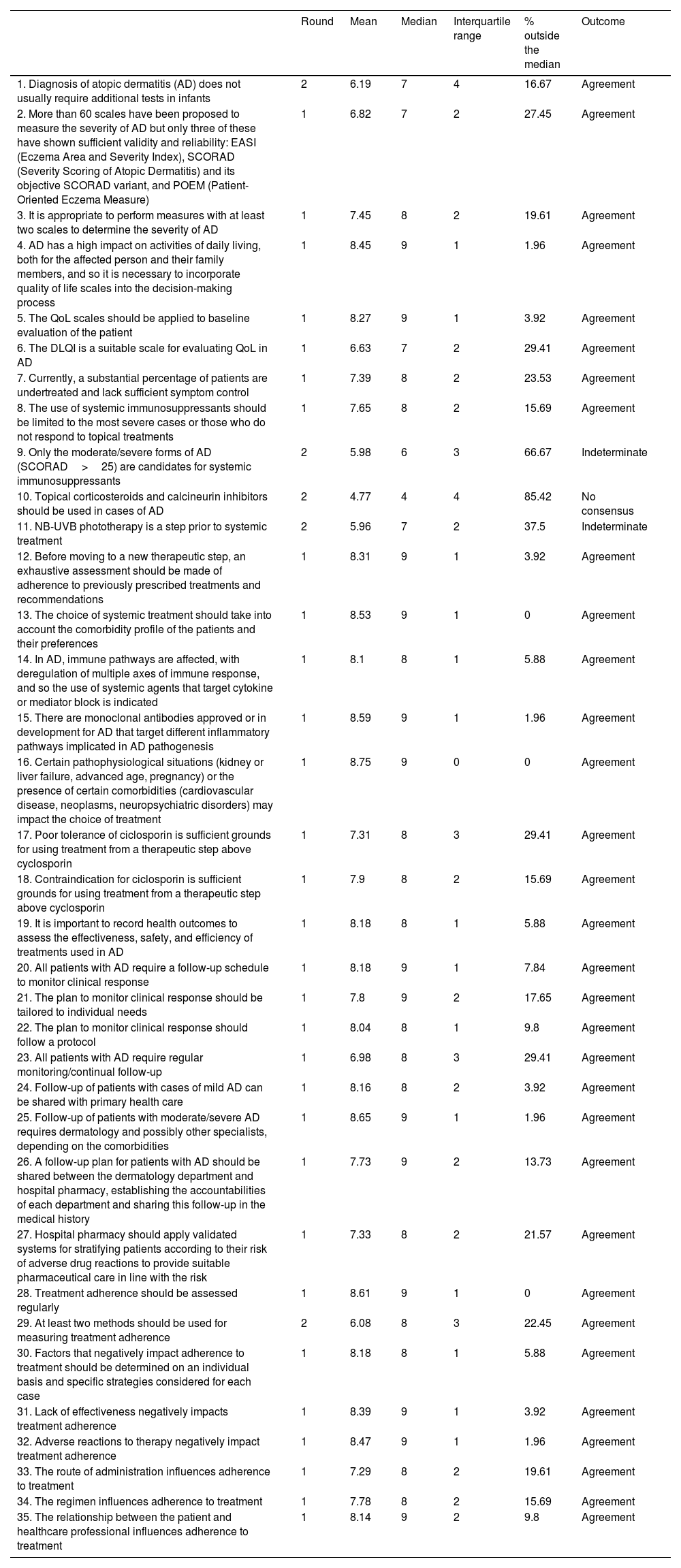

Management and assessment of the patientIn the first round, the experts reached consensus in 30 of the 35 assertions, corresponding to 86%. After the second round, the consensus increased to 32 out of 35, that is, a total of 91% (Table 1).

Block I. Management and assessment of the patient. Management and assessment of patients with moderate/severe AD. Assessment of response to treatment.

| Round | Mean | Median | Interquartile range | % outside the median | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (AD) does not usually require additional tests in infants | 2 | 6.19 | 7 | 4 | 16.67 | Agreement |

| 2. More than 60 scales have been proposed to measure the severity of AD but only three of these have shown sufficient validity and reliability: EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index), SCORAD (Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis) and its objective SCORAD variant, and POEM (Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure) | 1 | 6.82 | 7 | 2 | 27.45 | Agreement |

| 3. It is appropriate to perform measures with at least two scales to determine the severity of AD | 1 | 7.45 | 8 | 2 | 19.61 | Agreement |

| 4. AD has a high impact on activities of daily living, both for the affected person and their family members, and so it is necessary to incorporate quality of life scales into the decision-making process | 1 | 8.45 | 9 | 1 | 1.96 | Agreement |

| 5. The QoL scales should be applied to baseline evaluation of the patient | 1 | 8.27 | 9 | 1 | 3.92 | Agreement |

| 6. The DLQI is a suitable scale for evaluating QoL in AD | 1 | 6.63 | 7 | 2 | 29.41 | Agreement |

| 7. Currently, a substantial percentage of patients are undertreated and lack sufficient symptom control | 1 | 7.39 | 8 | 2 | 23.53 | Agreement |

| 8. The use of systemic immunosuppressants should be limited to the most severe cases or those who do not respond to topical treatments | 1 | 7.65 | 8 | 2 | 15.69 | Agreement |

| 9. Only the moderate/severe forms of AD (SCORAD>25) are candidates for systemic immunosuppressants | 2 | 5.98 | 6 | 3 | 66.67 | Indeterminate |

| 10. Topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors should be used in cases of AD | 2 | 4.77 | 4 | 4 | 85.42 | No consensus |

| 11. NB-UVB phototherapy is a step prior to systemic treatment | 2 | 5.96 | 7 | 2 | 37.5 | Indeterminate |

| 12. Before moving to a new therapeutic step, an exhaustive assessment should be made of adherence to previously prescribed treatments and recommendations | 1 | 8.31 | 9 | 1 | 3.92 | Agreement |

| 13. The choice of systemic treatment should take into account the comorbidity profile of the patients and their preferences | 1 | 8.53 | 9 | 1 | 0 | Agreement |

| 14. In AD, immune pathways are affected, with deregulation of multiple axes of immune response, and so the use of systemic agents that target cytokine or mediator block is indicated | 1 | 8.1 | 8 | 1 | 5.88 | Agreement |

| 15. There are monoclonal antibodies approved or in development for AD that target different inflammatory pathways implicated in AD pathogenesis | 1 | 8.59 | 9 | 1 | 1.96 | Agreement |

| 16. Certain pathophysiological situations (kidney or liver failure, advanced age, pregnancy) or the presence of certain comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, neoplasms, neuropsychiatric disorders) may impact the choice of treatment | 1 | 8.75 | 9 | 0 | 0 | Agreement |

| 17. Poor tolerance of ciclosporin is sufficient grounds for using treatment from a therapeutic step above cyclosporin | 1 | 7.31 | 8 | 3 | 29.41 | Agreement |

| 18. Contraindication for ciclosporin is sufficient grounds for using treatment from a therapeutic step above cyclosporin | 1 | 7.9 | 8 | 2 | 15.69 | Agreement |

| 19. It is important to record health outcomes to assess the effectiveness, safety, and efficiency of treatments used in AD | 1 | 8.18 | 8 | 1 | 5.88 | Agreement |

| 20. All patients with AD require a follow-up schedule to monitor clinical response | 1 | 8.18 | 9 | 1 | 7.84 | Agreement |

| 21. The plan to monitor clinical response should be tailored to individual needs | 1 | 7.8 | 9 | 2 | 17.65 | Agreement |

| 22. The plan to monitor clinical response should follow a protocol | 1 | 8.04 | 8 | 1 | 9.8 | Agreement |

| 23. All patients with AD require regular monitoring/continual follow-up | 1 | 6.98 | 8 | 3 | 29.41 | Agreement |

| 24. Follow-up of patients with cases of mild AD can be shared with primary health care | 1 | 8.16 | 8 | 2 | 3.92 | Agreement |

| 25. Follow-up of patients with moderate/severe AD requires dermatology and possibly other specialists, depending on the comorbidities | 1 | 8.65 | 9 | 1 | 1.96 | Agreement |

| 26. A follow-up plan for patients with AD should be shared between the dermatology department and hospital pharmacy, establishing the accountabilities of each department and sharing this follow-up in the medical history | 1 | 7.73 | 9 | 2 | 13.73 | Agreement |

| 27. Hospital pharmacy should apply validated systems for stratifying patients according to their risk of adverse drug reactions to provide suitable pharmaceutical care in line with the risk | 1 | 7.33 | 8 | 2 | 21.57 | Agreement |

| 28. Treatment adherence should be assessed regularly | 1 | 8.61 | 9 | 1 | 0 | Agreement |

| 29. At least two methods should be used for measuring treatment adherence | 2 | 6.08 | 8 | 3 | 22.45 | Agreement |

| 30. Factors that negatively impact adherence to treatment should be determined on an individual basis and specific strategies considered for each case | 1 | 8.18 | 8 | 1 | 5.88 | Agreement |

| 31. Lack of effectiveness negatively impacts treatment adherence | 1 | 8.39 | 9 | 1 | 3.92 | Agreement |

| 32. Adverse reactions to therapy negatively impact treatment adherence | 1 | 8.47 | 9 | 1 | 1.96 | Agreement |

| 33. The route of administration influences adherence to treatment | 1 | 7.29 | 8 | 2 | 19.61 | Agreement |

| 34. The regimen influences adherence to treatment | 1 | 7.78 | 8 | 2 | 15.69 | Agreement |

| 35. The relationship between the patient and healthcare professional influences adherence to treatment | 1 | 8.14 | 9 | 2 | 9.8 | Agreement |

With regard assessment of treatment, more than 60 scales have been proposed to measure the severity of AD; however, it was agreed that only three of these showed sufficient validity and reliability. These scales are the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), the Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD), and the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM). The experts, in addition, agreed that it is appropriate to use at least two of these scales to determine the severity of AD.

AD impacts the quality of life of the patients and their family members, and so the experts agreed to suggest the incorporation of scales of quality of life into decision-making. Of the available scales, the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is considered a suitable scale.

Therapeutic stepsThe panel agreed that there is currently a substantial percentage of patients who are undertreated and who lack sufficient symptom control.

Regarding the use of systemic immunosuppressants, the experts agreed that these should be limited to the most severe cases or those that do not respond to topical treatments.

In the case of topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors, there was no consensus that these should be used in all cases of AD. Likewise, there was no agreement that narrow-band (NB) UVB phototherapy should be a mandatory prior step before systemic treatment. In the case of ciclosporin, there was agreement that poor tolerance or a contraindication for this agent is sufficient grounds for proceeding to the next therapeutic step.

Control and follow-up of the patientThere was agreement that all patients with AD require regular monitoring and a follow-up schedule to assess clinical response. This should be protocolized and adapted to individual needs. There was also agreement that this plan should be shared between the dermatology department and hospital pharmacy, establishing the accountabilities of each department and sharing this follow-up in the medical records. In the case of mild AD, the experts agreed that follow-up should be shared with primary health care.

There was also agreement that hospital pharmacy should apply validated systems for stratifying patients according to their risk of adverse drug reactions to provide suitable pharmaceutic care according to risk.

Treatment adherenceThere was agreement that lack of effectiveness of treatment, side effects, route of administration, regimen, and relationship between healthcare professional and patient are factors that may impact adherence to treatment. Therefore, a consensus was reached to regularly measure adherence to treatment using at least two types of measure, such as the Green-Morinsky test and dispensing records,11 and to study individually which factors negatively impact adherence and propose specific strategies for improvement.

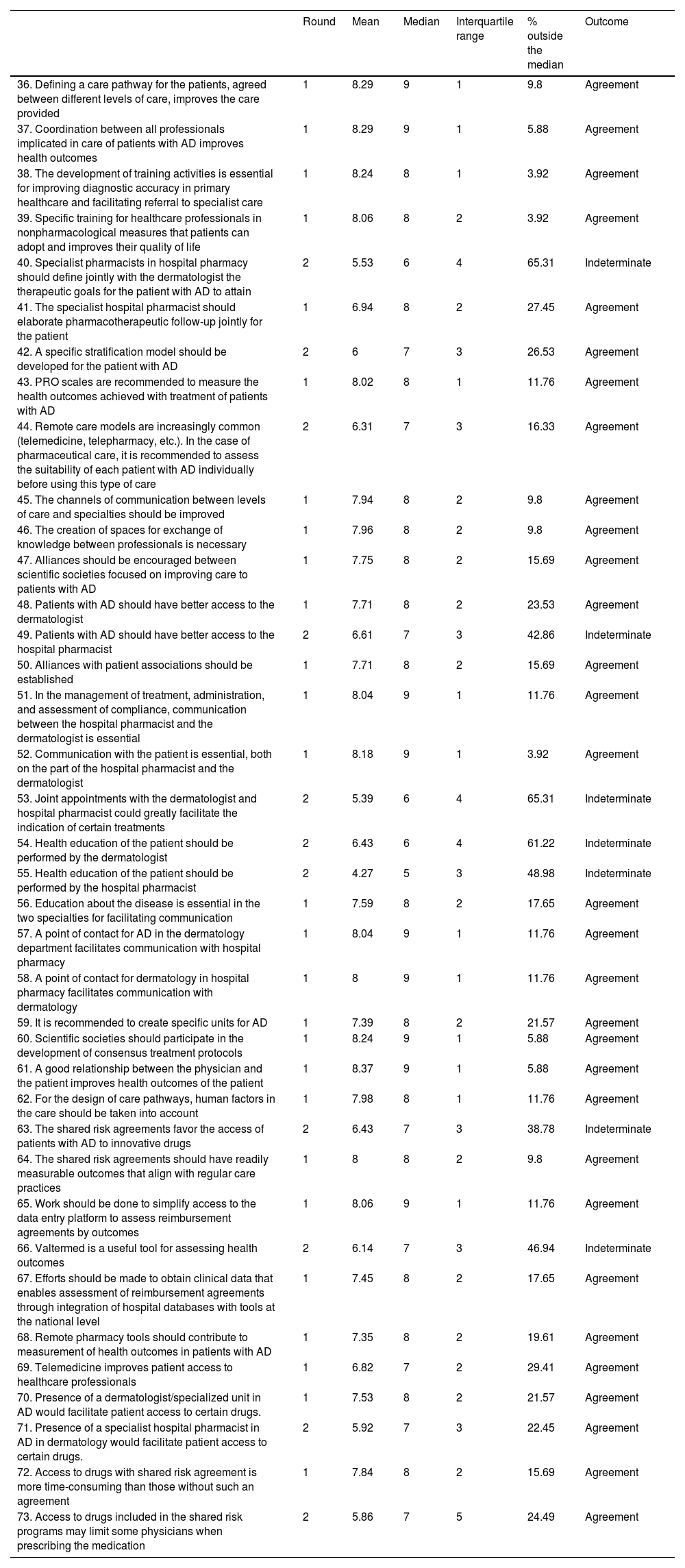

Collaboration between the dermatology department and hospital pharmacyIn this block, the experts reached a consensus in 27 of the 38 assertions, corresponding to 71%. After the second round, the consensus increased to 31 out of 38, thus attaining a total of 82% (Table 2).

Block II. Collaboration between the dermatology department and hospital pharmacy. Routes to improved patient care, care optimization, and improvement in the quality and effectiveness of care. Challenges in care management. Shared challenges.

| Round | Mean | Median | Interquartile range | % outside the median | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36. Defining a care pathway for the patients, agreed between different levels of care, improves the care provided | 1 | 8.29 | 9 | 1 | 9.8 | Agreement |

| 37. Coordination between all professionals implicated in care of patients with AD improves health outcomes | 1 | 8.29 | 9 | 1 | 5.88 | Agreement |

| 38. The development of training activities is essential for improving diagnostic accuracy in primary healthcare and facilitating referral to specialist care | 1 | 8.24 | 8 | 1 | 3.92 | Agreement |

| 39. Specific training for healthcare professionals in nonpharmacological measures that patients can adopt and improves their quality of life | 1 | 8.06 | 8 | 2 | 3.92 | Agreement |

| 40. Specialist pharmacists in hospital pharmacy should define jointly with the dermatologist the therapeutic goals for the patient with AD to attain | 2 | 5.53 | 6 | 4 | 65.31 | Indeterminate |

| 41. The specialist hospital pharmacist should elaborate pharmacotherapeutic follow-up jointly for the patient | 1 | 6.94 | 8 | 2 | 27.45 | Agreement |

| 42. A specific stratification model should be developed for the patient with AD | 2 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 26.53 | Agreement |

| 43. PRO scales are recommended to measure the health outcomes achieved with treatment of patients with AD | 1 | 8.02 | 8 | 1 | 11.76 | Agreement |

| 44. Remote care models are increasingly common (telemedicine, telepharmacy, etc.). In the case of pharmaceutical care, it is recommended to assess the suitability of each patient with AD individually before using this type of care | 2 | 6.31 | 7 | 3 | 16.33 | Agreement |

| 45. The channels of communication between levels of care and specialties should be improved | 1 | 7.94 | 8 | 2 | 9.8 | Agreement |

| 46. The creation of spaces for exchange of knowledge between professionals is necessary | 1 | 7.96 | 8 | 2 | 9.8 | Agreement |

| 47. Alliances should be encouraged between scientific societies focused on improving care to patients with AD | 1 | 7.75 | 8 | 2 | 15.69 | Agreement |

| 48. Patients with AD should have better access to the dermatologist | 1 | 7.71 | 8 | 2 | 23.53 | Agreement |

| 49. Patients with AD should have better access to the hospital pharmacist | 2 | 6.61 | 7 | 3 | 42.86 | Indeterminate |

| 50. Alliances with patient associations should be established | 1 | 7.71 | 8 | 2 | 15.69 | Agreement |

| 51. In the management of treatment, administration, and assessment of compliance, communication between the hospital pharmacist and the dermatologist is essential | 1 | 8.04 | 9 | 1 | 11.76 | Agreement |

| 52. Communication with the patient is essential, both on the part of the hospital pharmacist and the dermatologist | 1 | 8.18 | 9 | 1 | 3.92 | Agreement |

| 53. Joint appointments with the dermatologist and hospital pharmacist could greatly facilitate the indication of certain treatments | 2 | 5.39 | 6 | 4 | 65.31 | Indeterminate |

| 54. Health education of the patient should be performed by the dermatologist | 2 | 6.43 | 6 | 4 | 61.22 | Indeterminate |

| 55. Health education of the patient should be performed by the hospital pharmacist | 2 | 4.27 | 5 | 3 | 48.98 | Indeterminate |

| 56. Education about the disease is essential in the two specialties for facilitating communication | 1 | 7.59 | 8 | 2 | 17.65 | Agreement |

| 57. A point of contact for AD in the dermatology department facilitates communication with hospital pharmacy | 1 | 8.04 | 9 | 1 | 11.76 | Agreement |

| 58. A point of contact for dermatology in hospital pharmacy facilitates communication with dermatology | 1 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 11.76 | Agreement |

| 59. It is recommended to create specific units for AD | 1 | 7.39 | 8 | 2 | 21.57 | Agreement |

| 60. Scientific societies should participate in the development of consensus treatment protocols | 1 | 8.24 | 9 | 1 | 5.88 | Agreement |

| 61. A good relationship between the physician and the patient improves health outcomes of the patient | 1 | 8.37 | 9 | 1 | 5.88 | Agreement |

| 62. For the design of care pathways, human factors in the care should be taken into account | 1 | 7.98 | 8 | 1 | 11.76 | Agreement |

| 63. The shared risk agreements favor the access of patients with AD to innovative drugs | 2 | 6.43 | 7 | 3 | 38.78 | Indeterminate |

| 64. The shared risk agreements should have readily measurable outcomes that align with regular care practices | 1 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 9.8 | Agreement |

| 65. Work should be done to simplify access to the data entry platform to assess reimbursement agreements by outcomes | 1 | 8.06 | 9 | 1 | 11.76 | Agreement |

| 66. Valtermed is a useful tool for assessing health outcomes | 2 | 6.14 | 7 | 3 | 46.94 | Indeterminate |

| 67. Efforts should be made to obtain clinical data that enables assessment of reimbursement agreements through integration of hospital databases with tools at the national level | 1 | 7.45 | 8 | 2 | 17.65 | Agreement |

| 68. Remote pharmacy tools should contribute to measurement of health outcomes in patients with AD | 1 | 7.35 | 8 | 2 | 19.61 | Agreement |

| 69. Telemedicine improves patient access to healthcare professionals | 1 | 6.82 | 7 | 2 | 29.41 | Agreement |

| 70. Presence of a dermatologist/specialized unit in AD would facilitate patient access to certain drugs. | 1 | 7.53 | 8 | 2 | 21.57 | Agreement |

| 71. Presence of a specialist hospital pharmacist in AD in dermatology would facilitate patient access to certain drugs. | 2 | 5.92 | 7 | 3 | 22.45 | Agreement |

| 72. Access to drugs with shared risk agreement is more time-consuming than those without such an agreement | 1 | 7.84 | 8 | 2 | 15.69 | Agreement |

| 73. Access to drugs included in the shared risk programs may limit some physicians when prescribing the medication | 2 | 5.86 | 7 | 5 | 24.49 | Agreement |

Agreement was reached to implement care pathways for the patients, agreed between different levels of care, to improve the care provided to the patient, and to coordinate between all professionals to improve the outcomes of the care provided. The development of training activities is essential for improving diagnostic accuracy in primary healthcare and facilitating referral to specialist care. There was also agreement that specific training for healthcare professionals in nonpharmacological measures for the patients would improve their quality of life.

There was consensus that patients with AD should have better access to the dermatologist; however, there was a lack of agreement as to whether there should be better access to the specialist pharmacist.

With regards the remote models of care, the experts agreed, in the case of pharmaceutical care, that a patient should be assessed for suitability to receive this type of care. Moreover, there was consensus that the remote pharmacy tools should contribute to measurement of health outcomes in patients with AD. There was also agreement that telemedicine improves patient access to healthcare professionals.

Coordination and communication between levels of careThere was agreement that the channels of communication between levels of care and specialties should be improved. Knowledge exchange between professionals and establishment of alliances with scientific societies and patient associations were considered necessary for such communication. The experts also recommended that scientific societies participate in the development of consensus treatment protocols.

According to the experts, communication between the hospital pharmacist and the dermatologist is essential for managing treatment, administration, and assessment of compliance. It is also essential for both specialists to communicate with the patients. However, consensus was not reached as to whether an appointment with both professionals present could facilitate the indication of certain treatments, nor whether the hospital pharmacist should set the therapeutic goals of the patients jointly with the dermatologist.

The experts did agree though that the presence of a point of contact for AD within the dermatology department and the presence in the pharmacy department of a contact for dermatology would facilitate communication between the departments.

In the case of health education of the patient, the experts did not reach an agreement as to what should be covered exclusively by the dermatologist or the pharmacist.

Challenges in care managementThere was agreement that the presence of a dermatology point of contact for AD or a specialized unit, as well as a hospital pharmacists specialized in dermatology would facilitate patient access to certain drugs.

With regards the development of agreements on shared risk, the experts agreed that these should have readily measurable outcomes that align with regular care practices. Access to drugs included in the programs of shared risk is time consuming, and so certain physicians may be limited in prescribing the medication. However, the experts did not reach consensus on which agreements could help patient access to innovative drugs.

DiscussionModerate/severe AD still requires a complex approach, due to the multifaceted nature of the disease.4,7–9,12–14 An initial evaluation should be performed of the scope and severity of the disease in order to select the most suitable therapy.9

In addition to the conventional systemic treatments recommended by the European guidelines,15 new therapeutic families have recently become available (biologics and synthetic molecules). Through the use of these new agents, the goal is to regulate or inhibit the activity of different cell mediators implicated in the inflammatory pathways that underlie AD manifestations.3,16,17 Several biologics have been approved and many others are in development or can be used off-label in AD. We are still awaiting consensus guidelines to define the therapeutic steps with biologics. With regards the recommendations for systemic immunosuppressants, there is disagreement as to whether these should be administered to patients with moderate/severe AD (SCORAD>25); the experts noted that other variables should be taken into account such as the site of the lesions, the lack of response to other treatments, contraindications, and also quality of life. Moreover, although there is agreement that patients with severe forms (SCORAD>50) should be candidates for receiving these agents, as well as those with unsatisfactory response to topical treatments, it is of note that an algorithm has yet to be defined in the guidelines that indicates best time to start these agents. Nevertheless, the experts do recommend taking into account comorbidities and patient preference when choosing one treatment or another. We have used the SCORAD scale as we consider it the most complete scale that offers the evaluation best adapted to the clinical situation of the patient, even though the EASI scale is the most widely used in clinical trials.

With regards topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitor use in all patients, discrepancies were identified in the following: (1) the mildest forms, as the experts were of the opinion that these agents may not be necessary, with nonpharmacologic options being sufficient15 and (2) with the most severe forms, as they may not be sufficient from the outset. There was also a discrepancy for accepting NB-UVB phototherapy as a prior step to systemic therapy; the need to attend the hospital several days is a major limitation.

The interpretation whether the therapeutic goal has been achieved is a crucial question, which involves assessing several factors (clinical, patient satisfaction, safety, convenience) and for which there is still no consensus in Spain. The responses reported in this study record the opinion of each participant, based on their own experience.

An important aspect to consider in the assessment of treatment and one which the experts recommend to include in plans for patient follow-up are patient reported outcomes (PROs), in agreement with Cohen et al.,18 whose report identified them as an essential item. The complexity of management of patients with AD often means that the outcomes are not to their satisfaction. PROs complement the outcomes, thus improving case management.19

The experts recommend that follow-up of patients is shared between dermatology and hospital pharmacy, and they propose a multidisciplinary approach when AD is accompanied by other manifestations, both in adults and in children,20 as recommended by the technical report issued by Fundamed.9 In contrast, no consensus was reached on whether therapeutic goals should be defined jointly; some authors think that this should be the remit of the dermatologist with the pharmacists supporting the decisions made by the clinician. Analyzing the scores with the Delphi method, a wide range of responses was observed: there were similar numbers of votes in the ranges 1–3, 4–6, and 7–9. The discrepancy on this point is based on the idea that responsibility for diagnosis, choice of therapeutic goals, and choice of pharmacologic treatment correspond to the dermatologist. The pharmacist participates in this process as a collaborative figure, key for improving aspects of therapeutic compliance and safety, and reinforcing the suitability of the prescription. In this vision, the authors in disagreement do not consider necessary a joint assessment of the patient by the two specialties, as this does not add any clinical benefit. The design of a combined follow-up, based on alternative consultations between the two specialties, could add value to the process, as it would avoid unnecessary appointments for well-controlled patients (for example, spreading out the appointments), at the same time as ensuring compliance and detection of any potential safety issues.

Another point of contention was the possibility that dermatologist and hospital pharmacist see the patients together to facilitate the indication of certain treatments. The experts note that while this would be the ideal situation to know the patients better, it is not realistic; they propose alternatives such as interdisciplinary sessions, or that the hospital pharmacist rotates with dermatology.

To favor therapeutic compliance, the experts agree that there should be a good relationship between the patient and physician. They therefore recommend improving patient access to the dermatologist as also noted by Cohen et al.18 In this context, the remote care models will become increasingly important.21 With regards the greater patient access to the hospital pharmacist, there is a greater trend to agreement, but there is more variability than in other questions and there was no consensus reached. This could be the result of large differences in organization and resources in Spanish hospitals, such that the need for access is perceived according to the particular situation of the respondent. It is not unexpected that there was no consensus on this question, as the specific dedication of a pharmacist to patients with AD is not usual in many hospitals, understandably for reasons related to care requiring diversification to several specialties. This is a model that could be considered in most of the centers, with doubts about the potential benefits (basically, the dermatologists question the need for this ‘superspecialization’) on the one hand and the risks (greater work load and care pressure, delays in care, etc.) on the other. As a result, there are no comparative data to support one model or the other, and the range of opinions explains the lack of consensus. As an intermediate scenario and with greater practical applications, most hospital pharmacy departments opt for assigning tasks associated with dermatology to a stable part of their personnel (1 or 2 pharmacists), who thus acquire deeper knowledge of both the specialty and the local needs of each department and their patients.

With a view to facilitating therapeutic compliance, education of the patient and their carers is essential. They may be worried about the side effects of topical corticosteroids, have difficulty applying treatments, doubt their effectiveness, and need to be aware of other nonpharmacological measures to improve their quality of life.22–24 The experts were not in agreement as to who should be responsible for this task of education. Several noted that it would be the responsibility of both the dermatologist and hospital pharmacist, with support from nursing, as indicated in the guidelines,15 primary care, and community pharmacists, always aiming to transmit a uniform and agreed message.

In conclusion, at present, a series of challenges remain in the management of care of moderate/severe AD.18,25 The experts propose starting from an interdisciplinary approach to AD and improving communication and collaboration between dermatology and hospital pharmacy, with the aim of finding faster, more suitable, and more efficient solutions for patients and thus improving management of the disease.

FundingThis research project was financed by Lilly S.A.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the expert panel for their participation in the Delphi questionnaire, Luzán 5 Health Consulting for technical assistance and collaboration in logistical aspects of the meetings held during the project, and Estefanía Hurtado Gómez for her support in the preparation of this manuscript.